Al Flair

Boston Red Sox first baseman Al Flair answered a want ad and got a job playing baseball. The Sporting News explained: “An advertisement placed in the classified section of a Memphis newspaper [by Little Rock Travelers manager Doc Prothro] led to Flair’s entry into O.B. [Organized Baseball] A woman friend of the Flair family in Benoit, Miss., read the ad and, knowing that the Flairs had a son interested in a baseball career, mailed the advertisement to her New Orleans friends.”1 Flair himself said, “Yes, that ad was my start. I wrote to Prothro telling him all about myself, and he replied telling me to meet him in New Orleans when he brought his club here to play the Pelicans. I worked out with the Travelers and was signed to a contract.”2

Boston Red Sox first baseman Al Flair answered a want ad and got a job playing baseball. The Sporting News explained: “An advertisement placed in the classified section of a Memphis newspaper [by Little Rock Travelers manager Doc Prothro] led to Flair’s entry into O.B. [Organized Baseball] A woman friend of the Flair family in Benoit, Miss., read the ad and, knowing that the Flairs had a son interested in a baseball career, mailed the advertisement to her New Orleans friends.”1 Flair himself said, “Yes, that ad was my start. I wrote to Prothro telling him all about myself, and he replied telling me to meet him in New Orleans when he brought his club here to play the Pelicans. I worked out with the Travelers and was signed to a contract.”2

Albert Dell Flair was born in New Orleans on July 24, 1916, to Albert and Anna “Annie” Marguerite (Dell) Flair. Father Albert Flair’s parents were both of German ancestry, his father born in Germany and his mother born at sea of German parents. Albert became a pipefitter for an engineering firm in New Orleans. Albert’s younger siblings were Elmer, Merlin, and Betty Jane. By 1940, the year before young Albert broke in with the Red Sox, the elder Albert was working as a pump installer.

Albert attended McDonough School 23 for eight years, and Fortier High School for four more. He attended Louisiana State University, but wasn’t at LSU for that long. “The folks had sort of made up my mind I would go to LSU. Being a dutiful son, I went there a week, got acquainted with all the professors and told them goodbye. It was a record for going through college.”3

He had played baseball in high school and both American Legion and semipro ball as well. He played basketball and football, swam, and was on the track team. His aspiration was to become an erecting engineer. But he had enough talent to play the game professionally, which he proved after being given a chance. He did have that tryout with the Travelers. “After working out with the club I spoke to ‘Doc’ and he said I looked good. Before the team left, I signed a contract for 1937 and have been in the Red Sox chain ever since, hitting well over .300 each year and making several All-Star teams. I all ways (sic) did want to play big league ball.”4

Flair’s first assignment on the way to the big leagues was with the 1937 and 1938 Class-D Moultrie Packers (Georgia-Florida League). He hit .290 his first year, then .345 in 66 games in 1938, before being promoted to Class C, where he got into 31 more games, batting .291 for the Canton Terriers. Even after his 1937 season with Moultrie, Red Sox farm director Billy Evans saw him as a comer.5 As Flair progressed, he was looking more and more like a possible understudy for Jimmie Foxx at first base.

In 1939, Flair played the full season for the Class-B Piedmont League’s Rocky Mount Red Sox, batting .310. In 1940, he moved up to Class A, hitting .312 for the Eastern League’s Scranton Red Sox. His hometown newspaper was high on his prospects, writing in October that Flair was “considered a sure thing to play first base for the Boston Red Sox next year.”6

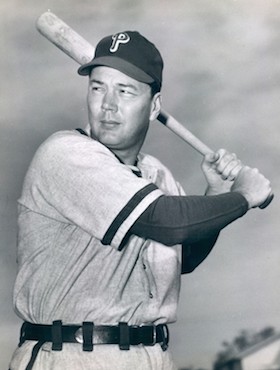

The big left-handed first baseman (he was 6-foot-4 and 195 pounds) played for the Baltimore Orioles in the International League in 1941. Both Tony Lupien and Flair were farmed out, Lupien to Louisville and Flair to Baltimore as partial compensation for the deal which brought shortstop Skeeter Newsome to Boston.7

He hit .298 for the Orioles, this time showing some power (11 home runs, three more than the four prior years combined). He won the Lou Gehrig trophy as the MVP of the Orioles. At the end of the season, he was brought up to Boston and got his chance to play big-league ball. There was no question but that the Sox were thinking ahead: “The first step in the reconstruction of the Red Sox for 1942 will be taken here tomorrow when Al Flair, 24-year-old son of New Orleans, takes over first base in the opener of a two-game weekend series.”8

Flair’s debut was on September 6, 1941. The second-place Red Sox were at Yankee Stadium, but were just over 20 games behind the first-place Yankees, who had already clinched the pennant. Skeeter Newsome hit a leadoff homer off Marv Breuer. The first four batters all reached base, two runs were in, and Flair came up with runners on first and second. He singled to load the bases. His next three times up, he grounded out. He pinch-hit in a couple more games, and came on in defense in his fourth game. His next two appearances were in starting roles, and he contributed a double in each game.

The final day of the 1941 season was at Shibe Park in Philadelphia. Neither team was worried about where they stood in the standings, but Ted Williams had seen his batting average slip to just under .400. He needed a base hit to push him over .400. Flair batted third in the order; Williams hit cleanup. Flair grounded out and flied out his first two times at bat; Williams singled and homered. Flair reached on an error his third time up, then ran to third on another Williams single. He scored on a long Bobby Doerr flyout. The Athletics were leading 11-4 at this point in the game. In the top of the seventh, after two-out walks to Dom DiMaggio and Lou Finney, Flair tripled to center field, driving them both in, then scored on Williams’s fourth hit of the game (.400 long since secured). They were Flair’s first two RBIs in the big leagues. The Red Sox won the game, 12-11. Flair was 0-for-4 in the day’s second game. Williams was 6-for-8 on the day and finished with a .406 average.

Al Flair’s two RBIs were his first, but also his last. The triple was his last base hit. He was 6-for-30 with two doubles and the triple, a .200 batting average, with three runs scored and the two runs batted in. He’d handled 67 chances at first base without an error. It looked like he was well-positioned for a shot at making the team in 1942. But he was drafted into the army, leaving his New Orleans home on December 4 to be inducted at Camp Livingston – three days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

By February, Flair was stationed at the Fort Bragg artillery replacement center in North Carolina. “I know I won’t play baseball for a long time,” he said, “There is another job at hand.”9 He was stationed at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, and Camp Sutton, North Carolina with the 166th Field Artillery Regiment, and “was honored with an Al Flair Day at Franklin Stadium, New Orleans on May 10, 1942, while visiting his parents on furlough from the Army.”10

Gary Bedingfield’s site further sates, “In 1944 he was with the 2nd Army Headquarters in Memphis, and played on the 8th Army Headquarters team managed by Hugh Mulcahy that barnstormed around Southwest Pacific bases in late 1944. He was later stationed in the Philippines and Japan.” The November 4, 1944, Times-Picayune featured a photograph of him and Ken Silvestri posing with natives of New Guinea, purportedly teaching them “the principles of American baseball.” At one point in late 1945, the Eighth Army Chicks were said to have won 37 consecutive games in the Philippines. They hadn’t been far behind the combat troops at Leyte the year before, and had to build their own housing and clear the land for a playing field.

Sgt. Flair was mustered out in early 1946, having missed four seasons while in the service. He joined the Red Sox for spring training in 1946. He had some trouble with his foot in the springtime, but made the team behind new acquisition Rudy York. Manager Joe Cronin preferred to play the veteran York, but he was disappointing in spring training. Flair had a shot to stick. He hadn’t really played that much in the army, but he was considered “a far better fielder” than York and veteran Boston sportswriter Ed Rumill believed “Al may lack Rudy’s distance power yet the younger man – as his size suggests – gets an extra-base kick into his clouts. And Al probably would be on base more often than his rival.”11

York rose to the challenge. On May 1, Flair was optioned to Boston’s Triple-A farm club in Louisville. He’d been on the roster of the pennant-winning 1946 Red Sox but never seen any action on the field of play. He was formally recalled to the Red Sox at the end of August, but not brought to Boston as a September call-up.

Flair hit .268 for Louisville, and signed again with the Red Sox for 1947, joining them for spring training. But his contract was sold outright to his hometown New Orleans Pelicans on March 31.

Playing for the Pels, he found some power, banging out a career-high 24 home runs and hitting .308. He played for New Orleans again in 1948 with similar results – fewer homers (22) but a higher average (.327).

He was with Atlanta for a while, but played most of 1949 and 1950 with Chattanooga, then finished his baseball career with Little Rock and finally Fort Worth in 1951.

Flair had married Betty Blancard in January 1948. They had three sons and a daughter.

He settled down after leaving the game and became president and salesman for Al Flair & Co., a janitor supply company in New Orleans. He had time for a little recreation as well and in 1958 was named Commodore of the New Orleans Power Boat Association. He was a frequent speaker at various athletic banquets in the area, a commander of American Legion Post 23, and was active in the Masonic Order, and some New Orleans Carnival organizations. He sold the company to Manny’s Sanitary Supply and worked for them before retirement.

After a brief illness, Flair died in New Orleans on July 26, 1988.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Flair’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Val J. Flanagan, “Home-Bred Flair Perks Pels With Home Runs,” The Sporting News, August 6, 1947: 29.

2 Ibid. Flair later said the woman who sent the clipping had written on it “Here’s your chance to become a second Bill Terry.” John Drohan, “Bill Terry Boyhood Idol of First Sacker Al Flair,” Boston Traveler, March 27, 1946: 21.

3 John Drohan.

4 Handwritten note signed “Flair” and found in Flair’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

5 Monte Cross, “At Short Range,” The Repository (Canton, Ohio), January 30, 1938: 38.

6 Wm. McG. Keefe, “Viewing the News,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, October 6, 1940: 62. Foxx was, though, almost certain to return and Tony Lupien ranked a bit higher on the depth chart than Flair. As John Kieran of the New York Times pointed out near the end of spring training, “There were kind words for big Al Flair, the young fellow with the Fenway Millionaires, but unless James Emory Foxx breaks a leg or is shifted to some other positions, what could Flair do in a Red Sox uniform?” Kieran’s column appeared in the Boston Herald, March 28, 1941: 32.

7 Arthur Sampson, “Now Louisville Has its Doubts,” Boston Herald, April 3, 1941: 23.

8 Gerry Moore, “Flair To Take Over Initial Sack in Renovated Red Sox Lineup Today,” Boston Globe, September 6, 1941: 7.

9 Associated Press, “Flair Through With Baseball for Duration,” Christian Science Monitor, February 4, 1942: 14.

10 http://www.baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/flair_al.htm

11 Ed Rumill, “Al Flair May Beat Out York For First Base on Red Sox,” Christian Science Monitor, March 26, 1946: 14.

Full Name

Albert Dell Flair

Born

July 24, 1916 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

Died

July 26, 1988 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.