Paul Krichell

When he was 36 years old Paul Krichell found himself at something of a crossroads in his baseball life. After many years playing professional baseball—including two nondescript seasons in the majors—Krichell had become a minor-league manager. Near the end of the 1918 season, however, Krichell resigned and quit Organized Baseball in the wake of a spat with the league president. Krichell spent one year in the college ranks before concluding that he wanted a career in major-league baseball.

When he was 36 years old Paul Krichell found himself at something of a crossroads in his baseball life. After many years playing professional baseball—including two nondescript seasons in the majors—Krichell had become a minor-league manager. Near the end of the 1918 season, however, Krichell resigned and quit Organized Baseball in the wake of a spat with the league president. Krichell spent one year in the college ranks before concluding that he wanted a career in major-league baseball.

To re-enter the professional game, Krichell joined the Boston Red Sox as a coach and scout. When Boston manager Ed Barrow moved to the Yankees, he took Krichell along as a scout. On the basis of his keen eye for baseball talent and an ability to acquire it, Krichell quickly ripened into the Yankees’ top scout. Over his 37 years with New York, Krichell landed many of the players who would make the Yankees one of great dynasties in American sports. Krichell’s successes included both quality—such as Lou Gehrig, Tony Lazzeri, Phil Rizzuto, and Whitey Ford—and quantity.

Paul Bernard Krichell was born in Paris, France, on December 19, 1882. Modern sources (and Krichell himself) universally identify his birthplace as New York, but an examination of the source materials clearly indicates he was born overseas.1 When he was about 5, Krichell’s parents, Martin and Gaustave Kreschel, immigrated to the United States with Paul, his two older sisters, Katherine and Annie, and a baby daughter, Alice. Another daughter, Eugenie, was born shortly thereafter. Both parents were born in western Germany in the late 1840s; the young family moved to France sometime before Paul was born.

Krichell grew up in New York in the late 19th century playing baseball like many immigrant American boys. The 1900 census located the Krichells in Queens, but all later newspaper references to his youth place him in the Bronx. Most likely the family moved (possibly more than once), and he lived in both boroughs. A catcher from the start, Krichell was quickly recognized as one of the area’s top players and began playing in what sportswriter Fred Lieb described as “the golden era of semiprofessional baseball in New York.” Krichell first played with an organized team in the Hudson River League in 1903. He later told Lieb that in 1905 two men active in New York semipro baseball stopped by his home to recruit him as a backup catcher for the Yankees. They told Krichell that New York manager Clark Griffith was short of catchers because of injuries and needed a temporary reserve. Krichell was with the Yankees for about a month but never saw any major-league action; he was mainly used to warm up the pitchers.2

After his short stint with the Yankees, Krichell broke into Organized Baseball as a player with Hartford in the Connecticut League in 1906. In 1907 he joined Newark in the Class A Eastern League, one step below the majors at the time. Krichell played only sparingly at Newark and was dealt to Montreal during the 1909 season. In 1910, playing for new manager Ed Barrow—for whom he would later work during the majority of his career as a Yankees scout—Krichell recorded his only season of more than 100 games played. He hit .249 with 14 doubles and no home runs; not a great season, but in an age when catchers were evaluated extensively on their defense, Krichell was receiving some major-league notice.

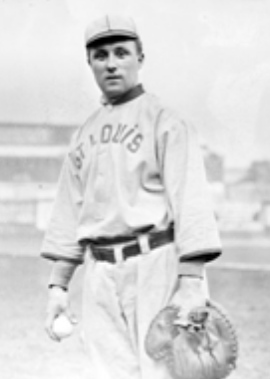

In 1911 the St. Louis Browns acquired Krichell, and at age 28 he left the Northeast for the first extended time in his life. Nicknamed Gertie, at only 5-feet-7 and 150 pounds, the bowlegged Krichell was one of the smallest catchers in baseball. Nevertheless, Krichell was described as “built like a chunk of granite” and reputed to have a fairly strong throwing arm.3

Krichell told two stories of his days with the Browns that bear repeating. While he was catching one day against the Detroit Tigers with Ty Cobb, one of baseball’s most aggressive baserunners, on first base, Cobb got a great jump on a steal attempt. Krichell threw the ball to third, yelling, “Catch him when he comes around there.” St. Louis writer Harry Neily saw neither merit nor humor in Krichell’s action and roasted him in the paper. Krichell, however, maintained he was not clowning, and that it was an intelligent strategy: Pitcher Barney Pelty had a long windup and “in the event [Cobb] failed to pause [at second], I wanted to make sure I would get him at third base.”4

The other anecdote related to one of the catching crazes at the time: catching balls thrown from the top of the Washington Monument. Both Billy Sullivan and Gabby Street had gained a measure of fame for this, and Krichell wanted to try it, too. On a road trip to Washington, Hap Hogan volunteered to go to the top of the monument and send down a baseball. According to plan, Hogan first released two balls so that Krichell could gauge the wind and speed. Instead of releasing one more ball for Krichell to catch, however, Hogan let loose with a whole bag of baseballs. When Krichell saw the air filled with baseballs he put his hands over his head and ran for cover.5

After hitting .217 with no home runs in 59 games for the Browns in 1912, Krichell would never again appear in the major leagues as a player. He joined Kansas City in the Double-A American Association for the 1913 season. For the next several seasons he bounced around the high minors as a backup catcher: From 1914 through 1916 he played in the International League for Buffalo, Toronto, Richmond, and then back in Toronto. Krichell turned his best season at the plate in 1914 when he hit .346 in 191 at-bats. At this time Organized Baseball was challenged by the self-proclaimed major Federal League. The new league raided the established majors and high minors for players, whacking the International League particularly hard. In 1915 Krichell was rumored to have jumped Richmond to join Brooklyn in the Federal League. Krichell, though, never played for the outlaws, and after the Feds disbanded following the 1915 season Krichell remained in the International League.

For 1917 the Bridgeport Americans of the Class B Eastern League hired Krichell as player-manager. By this time, however, he recognized his declining skills and played himself only sparingly. He finished a couple of games below .500 in 1917, but in 1918 under wartime conditions he assembled one of the top teams in the league. The Sporting News labeled Krichell’s team “All Nations,” because of its many nationalities, including Japanese player Andy Yim and infielder Billy Lai, credited by The Sporting News as being the first Chinese player in Organized Baseball.6 Lai had been signed in the spring of 1918 by Phillies manager Pat Moran and optioned to Krichell in Bridgeport.7

Krichell’s aggressive style caused him some problems. By the end of June 1918 he led the league in fines. League President Dan O’Neill twice fined Krichell $20 for games in which he was ejected. More substantially, Krichell’s squad stood 23-2 on June 22 when O’Neill fined him $40 and reversed two Bridgeport victories in June because the club used a player, catcher Charles Connolly, who was not under contract and was on the suspended list. Having the two wins thrown out in what then became a much closer pennant race infuriated Krichell. He resigned on June 26 and lashed out at O’Neill: “I have only to say that I am through with baseball when men like Dan O’Neill are allowed to run baseball leagues. … When O’Neill and his crowd threw out those two games on me which my club won fair and square, I told [Bridgeport] president [C.P.] Lane that I was going to get through.”8

A dejected Krichell left Organized Baseball and for 1919 accepted a job coaching the New York University baseball team. After one season in the college ranks, however, Krichell hoped to return to professional baseball. His old friend and Montreal manager, Boston Red Sox manager Ed Barrow, hired him to help coach and scout. Barrow’s boss, Harry Frazee, had just sold Babe Ruth to the Yankees and was on an austerity kick; Krichell could help find new talent and improve that already on hand. When the Yankees hired Barrow as their de facto general manager after the 1920 season, he took Krichell along as a scout.

At this time, before the introduction of farm systems, most major-league players were acquired from the independent high minor leagues based on recommendations from scouts. Major-league scouts sought amateur talent as well, but given the restricted number of slots on a 40-man roster, teams were limited in who they could sign. With the Yankees, Krichell joined a small scouting staff and was charged with primarily scouting the college and semipro ranks. For the rest of his life until his death 37 years later, Krichell scouted for the New York Yankees.

One of the first collegians Krichell signed was also his best. In the spring of 1923 he scouted a game between Columbia and Rutgers in New Brunswick, New Jersey. On the train ride back to New York, Krichell grilled Columbia manager Andy Coakley about Lou Gehrig—then primarily a pitcher—who had hit two home runs in the game. Coakley spoke highly of his charge, and Krichell called in fellow Yankees scout Bob Connery for a second opinion. Upon further review, Krichell and Connery liked what they saw, and the Yankees signed the future Hall of Famer for a $1,500 bonus and a salary of $400 per month.

With Babe Ruth on board and Barrow working in the front office, the Yankees won their first pennant in 1921. The club repeated in 1922 and in 1923 won the franchise’s first World Series championship. Krichell quickly became Barrow’s favorite scout and trusted adviser. In 1925, when Babe Ruth developed his world-famous stomach ache during spring training, Barrow dispatched Krichell south to accompany Ruth back north on the train. By the time the train reached New York, Ruth was delirious and very ill. The chaotic situation in the train station with thousands of well-wishers and no way to maneuver the stretcher through the train door sorely tried Barrow (who met the train at the station) and Krichell. Eventually the two found a mechanic to remove the bars from the windows, pulled Ruth from the train, and sneaked up a freight elevator to a waiting ambulance.

After the disastrous 1925 season, Barrow reorganized his scouts. He hired “Vinegar Bill” Essick to scout the West and Eddie Herr, a former Detroit Tigers scout, whom he assigned to the Midwest. Holdovers Bob Gilks and Ed Holly focused on the South and East respectively. Krichell remained principally responsible for the colleges. Connery purchased a controlling interest in the St. Paul franchise in the American Association and assumed its operations.

Krichell was actively involved in some of the Yankees’ first big dollar acquisitions from the high minor leagues. He later described one of his first, the purchase of pitcher Walter Beall from Rochester, as his greatest disappointment.9 Krichell had better success a year later with future Hall of Fame second baseman Tony Lazzeri, who was tearing up the long-season Pacific Coast League. Krichell traveled to Salt Lake City to scout him and liked what he saw, although several teams showed some reservation because Lazzeri was epileptic. Nevertheless, Krichell recommended Lazzeri to Barrow despite his price tag of $50,000 and five players—a huge outlay for the time. Given the cost, Barrow dispatched Holly to confirm Krichell’s judgment and practically ordered ex-scout Connery, now in St. Paul and no longer a Yankees employee, to also validate Krichell’s assessment.

Barrow often dispatched his scouts to review prospects on short notice. While in Knoxville, Tennessee, Krichell received one of Barrow’s patented telegrams directing him to Durham, North Carolina, to scrutinize outfielder Dusty Cooke in the low minors. Once the owners realized the Yankees were pursuing Cooke they made sure other teams knew of Cooke’s availability and of the Yankees’ interest in order to push the price. Krichell eventually outmaneuvered the other scouts and landed Cooke but for the mushroomed price of $15,000. Krichell considered Cooke one of the best prospects he ever saw—while a Yankee farmhand in 1929 he hit .358 and led the American Association with 33 home runs and 148 RBIs. But Cooke severely separated his shoulder in 1931 in Washington and never realized his potential.

Krichell liked to point out the serendipity that could result from hard work and scouting contacts. While in Durham he remembered that a local physician and former ballplayer recommended Duke college player Billy Werber. Krichell and fellow Yankees scout Johnny Nee tracked and outbid several teams for Werber, who went on to a fine major-league career.10

Despite some effort, Krichell failed to land another future Hall of Fame first baseman in the late 1920s. Along with several other teams, he was pursuing Jewish prep phenom Hank Greenberg. Greenberg, who grew up in the Bronx, seemed a natural for the Yankees. But Krichell and Barrow arrogantly overplayed their hand. They started with a bonus offer of only a token $1,000 before raising it in response to competing bids. Barrow condescendingly warned Greenberg’s father of the temptations of playing far from home, and Krichell, as Greenberg remembered, laughed off his concerns of getting stuck behind Lou Gehrig by remarking that Gehrig was “all washed up.”11

Krichell had better luck with another product of the Bronx, Fordham University pitcher Johnny Murphy, who became a stellar relief pitcher. Krichell also signed hurler Hank Borowy from Fordham, outhustling scouts from the Dodgers, Red Sox, Giants, Cubs, Athletics, and Senators, and agreeing to pay an $8,000 bonus. When Krichell first delivered a contract calling for Borowy to start at Class A Binghamton, Borowy refused to sign it, arguing that he should start at Double-A Newark. Krichell agreed, but when he produced a fountain pen for Borowy to sign with, it failed to write. Krichell left to get another pen; when he returned Borowy insisted on $500 more, to which Krichell grudgingly agreed.12

Barrow relied on Krichell as an extra set of eyes and ears and as surrogate for baseball matters outside of New York. During the offseason Krichell often traveled to the Yankees players’ residences to check up on their conditioning and health. In 1928, when the Yankees purchased their first farm club, in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, Barrow sent Krichell to close on the acquisition. When Ruppert and Barrow decided they wanted to pursue Joe McCarthy as manager after the 1930 season, Barrow dispatched Krichell to Philadelphia to accompany him back to New York for a job interview. Krichell also helped out by signing Babe Ruth’s name to autographed baseballs when the slugger could not be bothered.13

By the early to mid-1930s the Yankees had launched their farm system and needed to increase the focus on amateur ballplayers to stock the organization. In this era before the amateur draft, scouts had wide latitude to find and then sign the best prospects. To add another source of players, Krichell recalled convincing Barrow and farm director George Weiss to organize a camp for prep stars in the summer of 1937. From this camp the Yankees landed future Hall of Fame shortstop Phil Rizzuto, one of 56 kids at the school and one of the smallest. Because he had received four letters touting Rizzuto—the Yankees received roughly 2,000 a year—he gave Rizzuto an extra look despite his stature. Krichell took a flyer on the youngster, signing him to a contract and farming him to the low minors.14

Scouting had its physical risks. In the summer of 1938 Krichell was hit in the head with a ball in Newark while evaluating some young hopefuls. A couple of months later he was still getting headaches and went to a doctor who X-rayed his head and diagnosed him with a fractured skull.15

In the spring of 1939 Krichell became enamored with a device to help pitchers with their control. The contraption consisted of a large piece of canvas held vertical by two steel poles. On the canvas was a picture of a right-handed batter and a catcher. Five holes were cut in the canvas: one at each shoulder and knee of the catcher and one in the center of the chest protector. Krichell brought one down to spring training to help teach his young pitchers control.16

In 1940 Krichell braved a torrential rainstorm to sign Frank Shea. While in high school Shea often moved back and forth between pitcher and right field during games, so Krichell arranged for Shea to pitch with a semipro team to focus on his pitching. After Shea tossed two no-hitters, Krichell recognized he needed to sign him quickly. While on his soggy journey to Connecticut, Krichell pulled over to wait out the storm; a state trooper stopped and accused the idling Krichell of sideswiping a truck earlier. Just before the officer was about to haul Krichell to jail, Krichell pleaded that he just needed to get to the Shea house. Once the trooper realized Krichell’s mission he eagerly escorted him to his prospect.17

During World War II the scouting focus temporarily shifted away from top amateurs to players not required by the armed forces or essential war industries. With the end of the war and the release of pent-up demand, pursuing top prospects became even more competitive. Krichell was 63 in 1946, but despite his age he maintained his love of scouting and the hunt for baseball players.

He invited Whitey Ford to a tryout after the high-school lefty wrote him a letter. Ford was both a first baseman and pitcher, but at only 5-feet-6 Krichell recognized his limitations as a first baseman. He took Ford aside after the tryout and spent about 15 minutes working with him on a curveball. Krichell later remarked: “I gave him a few pointers so he wouldn’t feel too bad about being turned down. We do that with all the kids who haven’t got what it takes. If we can’t make ballplayers out of them, we try to send ’em away as Yankee fans.” Five months later Ford had grown and with Krichell’s curve developed into an excellent pitcher. Krichell outdueled the Giants for his services, landing Ford for $7,000, a decent but not huge bonus for the time.18

By the late 1940s, as postwar prosperity kicked in and without an amateur draft to restrict competition, bonuses skyrocketed. Krichell made his last significant signing in early 1955 when he landed shortstop Tom Carroll. After his freshman year at Notre Dame, the New York native declared himself ready for professional baseball. Krichell offered a $40,000 bonus and prevailed over 12 other teams in the frenzy to sign Carroll.

After arriving in New York as a youth, Krichell lived the rest of his life there, mostly in the Bronx. In 1907 he married Mary Murphy, also from New York. Once on the Yankees, Krichell and Mary, known to the players as Aunt Mamie, spent every spring in Florida at training camp.19 By the late 1930s, Krichell often spent a couple of weeks in the offseason relaxing with Barrow at Boston Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey’s hunting preserve in South Carolina. In 1953 Krichell became the first scout to receive the prestigious William Slocum Memorial Award for “outstanding service over a long period of years,” awarded annually by the New York Chapter of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America.20

Krichell died at home on June 4, 1957, after a two-year battle with cancer of the lymphatic tissue. He was 74 years old. He was buried in Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York. Mary had died earlier that year; Krichell left behind a daughter, four sisters, and a number of grandchildren and great-grandchildren. He also left a baseball legacy as possibly the greatest of all ivory hunters.

Photo credit

Courtesy of Bill Hickman.

Sources

The historical Sporting News was extremely useful for following Krichell’s baseball life. For major-league statistics I principally used www.baseball-reference.com and The ESPN Baseball Encyclopedia edited by Gary Gillette and Pete Palmer. Krichell’s file at the A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum contained a number of interesting items. For minor-league records I relied mainly upon information ordered from Ray Nemec, the SABR Minor League Database, and Baseball America’s Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Third Edition). The SABR Scouts Committee “Who Signed Who” database is a valuable resource for providing leads in researching a scout’s career. The census and other family information available at Ancestry.com proved extremely helpful for personal information generally unavailable in published sources. The author’s biography of Ed Barrow, Ed Barrow: The Bulldog Who Built the Yankees’ First Dynasty (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008) offers a brief history of Krichell’s baseball life, the story of several of his more important signings, and useful background on the Yankee scouting system. The articles by Camerer and Heinz provide good background on Krichell and some of his player signings. The task of tracking down the many references to Krichell in published sources was eased tremendously by The Baseball Index.

Notes

1 Based on documents available at Ancestry.com, Krichell was clearly born in France and most likely Paris.

(a) On his sworn World War II draft registration card Krichell identified his birthplace as Paris.

(b) His World War I draft card does not ask for a place of birth but it does ask for citizenship information. Krichell did not check the native-born box; instead he checked the box labeled “Citizen by Father’s Naturalization before Registrant’s Majority,” indicating he was not born in the US.

(c) In the 1900 census, at which time Krichell was still living at home, his birthplace was listed as France. The census information also notes that he came to the US in 1886.

(d) In the 1910 census Krichell is now head of household. His place of birth is not particularly legible, although it is clearly not New York. The Ancestry.com interpreter for this census lists his birthplace as France. The census lists the year he came to the US as 1887.

2 Fred Lieb newspaper column, unidentified clipping in Krichell’s Hall of Fame file.

3 Atlanta Constitution, May 5, 1912.

4 The Sporting News, February 14, 1935; Fred Lieb newspaper column, unidentified clipping in Krichell’s Hall of Fame file.

5 Fred Lieb newspaper column, unidentified clipping in Krichell’s Hall of Fame file.

6 The Sporting News, February 14, 1935.

7 Hartford Courant, May 19, 1918.

8 Hartford Courant, June 19, 1918, and June 28, 1928.

9 The Sporting News, April 20, 1939.

10 The Sporting News, April 20, 1939; May 1, 1941; W.C. Heinz, “I Scout For the Yankees,” (Collier’s, July 11, 1953).

11 Daniel R. Levitt, Ed Barrow: The Bulldog Who Built the Yankees’ First Dynasty, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008).

12 The Sporting News, January 28, 1943

13 The Sporting News, March 5, 1947.

14 The Sporting News, March 27, 1941; W.C. Heinz, “I Scout For the Yankees,” (Collier’s, July 11, 1953).

15 Paul Krichell as told to Jerry D. Lewis, “You Can Never Tell About a Rookie,” Liberty (May 25, 1940).

16 New York Daily Mirror, February 22, 1939.

17 Milton Gross, “Rookie of the Year,” Saturday Evening Post (July 26, 1947).

18 Stanley Frank, “The Yankees’ Southpaw Wizard,” Saturday Evening Post (May 12, 1956); Frank Graham, “Hard-Boiled Yankee,” Sport (November, 1956).

19 The Sporting News, April 24, 1957 and June 12, 1957; New York Times, June 6, 1957.

20 The Sporting News, December 30, 1953.

Full Name

Paul Bernard Krichell

Born

December 19, 1882 at Paris, (France)

Died

June 4, 1957 at Bronx, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.