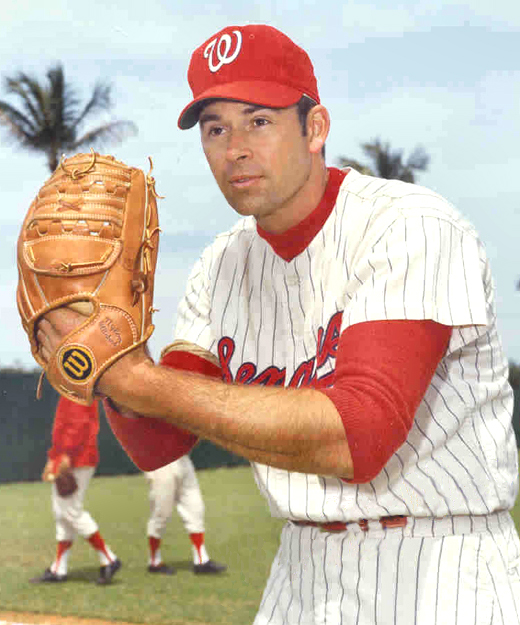

Dave Baldwin

Dave Baldwin didn’t talk to the baseball or scream at the hitters. Offering no self-styled Mark Fidrych or Al Hrabosky theatrics on the mound, the relief pitcher was a quiet guy to the point of being shy, almost unnoticeable.

Dave Baldwin didn’t talk to the baseball or scream at the hitters. Offering no self-styled Mark Fidrych or Al Hrabosky theatrics on the mound, the relief pitcher was a quiet guy to the point of being shy, almost unnoticeable.

Yet in 176 games over six seasons with the Washington Senators, Milwaukee Brewers and Chicago White Sox, Baldwin fashioned a big-league career distinguishable for its unusual approach. As he informed a quizzical President Richard Nixon one night in the dugout, “I’m the pitcher who throws funny.”

Pushing off the rubber, the Arizona native resembled the USS Baldwin — he was a submarine pitcher. He delivered it side-arm, too. For certain, the right hander was someone who went against the conservative MLB grain of the 1960s and ‘70s, when the drop-down pitching style was ridiculed or roundly discouraged.

“I had managers tell me, ‘You throw like a girl,’ ” he said.

Baldwin would slowly swivel his body so that he faced left field in mid-windup, often aim the ball well behind a right-handed hitter’s back to the point it seemed unnatural, and, picking up momentum, he would dip into a crouch and snap off an assortment of sweeping and baffling pitches.

Frank Robinson couldn’t hit him, going 2-for-13. Norm Cash was 1-for-7. Bob Allison went 0-for-7, with five strikeouts. Al Kaline was a paltry 1-for-6. Even Reggie Jackson got shown up by this combo submariner/side-armer in one of two official at-bats.

“I threw a really good pitch, a side-arm curveball,” Baldwin said of a memorable June strikeout of “Mr. October” in 1970. “It broke way outside. It broke over the outside corner. He just took it.”

Baldwin’s unique pitching approach brought him to the majors at a relatively late baseball age (28) when it appeared nothing else would. At the University of Arizona, he was the traditional, hard-throwing prospect until he heard a loud pop in his forearm and felt his elbow disintegrate. In the aftermath, he was a minor-leaguer destined for mediocrity and early baseball retirement before lowering his arm slot and raising his possibilities. His time in the big show (1966-70, ’73) would prove as inspirational as it was unlikely.

“When I injured my arm, my career should have been over,” Baldwin said. “I shouldn’t have pitched anymore.”

There was nothing wrong with his brain. Baldwin, a noted deep-thinker who ultimately studied zoology and anthropology and earned a PhD in genetics and M.S. in systems engineering, tinkered long and hard at the pitching drawing board until he came up with a way to live out his baseball dream.

“I think his biggest accomplishment was making it to the big leagues after hurting his arm,” said Jim French, a former catcher on the receiving end of Baldwin’s pitches for 26 of his 234 big-league games, all spent with the Washington Senators (1965-71). “I’m probably more impressed with that now than I was then.”

David George Baldwin was born, with two sound arms, in Tucson, Arizona, on March 30, 1938, the only child of Harold and Evelyn Baldwin. Of British and French ancestry and boasting of descendents who fought in the Civil War, his parents were college-educated working professionals who hailed from the Midwest. They met at the University of Illinois, married in Chicago and eventually moved to the Southwest to deal with pressing health concerns; Evelyn was diagnosed with tuberculosis, though family members were never quite sure what it was that ailed her. Harold was a teacher, principal, machinist, lumber mill salesman, steel mill foreman and contractor; Evelyn a librarian, architect and artist.

If there was an early baseball connection to this family, it was a glorious one: Baldwin’s father, Harold, a one-time youth sandlot player, attended Game 3 of the 1932 World Series in Chicago, witnessing Babe Ruth’s supposed legendary home run call.

Dave Baldwin fell headlong into the game before entering his teens, if for no other reason than to please his father. Their games of catch morphed into a singular obsession for the aspiring player. As the younger Baldwin got more serious about pitching, he threw alone from a homemade mound to a contraption labeled “the box,” a clever device dreamed up by his engineering-minded father. Built-in springs and panels effectively returned balls to the pitcher.

For 22 years, Baldwin honed his pitching talent using “the box,” from age 15 to his final pro baseball season. To the end, his father stood off to the side, critiquing his son’s experimental deliveries.

Growing up in the desert, Baldwin drew added baseball motivation by watching the Cleveland Indians annually show up for spring training in Tucson with an impressive pitching contingent always in tow. Bob Feller, Bob Lemon, Early Wynn, Hal Newhouser, Mike Garcia and Satchel Paige had his rapt attention. Baldwin watched their every move. He tried to pitch like them. He even tried to spit like them.

Resisting offers to turn pro early, Baldwin went from Tucson High School and the semipro leagues to his home-town University of Arizona. All went well for this promising fastballer — he was a combined 40-6 in high school and college — until the third outing of his UA sophomore season, a 1958 home game against the University of Utah. In the sixth inning, his third or fourth pitch was an unmitigated disaster. It was an overhand curveball, and one that permanently altered his baseball mechanics.

“I felt confident I could throw the ball by anybody, and that ended with one pitch,” Baldwin said. “Everything in my elbow collapsed.”

Medically speaking, these were archaic baseball times. Tommy John surgery was still years away. There were no specialists to consult. There was no place to go for relief or repair except to sit in the whirlpool and let the bubbly water do whatever soothing magic it could. It took Baldwin a while to fully straighten his right arm again. His only option was to pitch through his troubles and keep his mouth shut and soak in the tub, which he resolutely did.

“Most guys with arm trouble kept pitching and worked their way through it back then, but a lot of guys quit,” Baldwin said. “They had a chance until they hurt their arms. The ones who starred in the majors had no arm injuries or not very severe ones.”

Even with a noticeable drop in velocity, Baldwin came back and threw well enough as a junior to pitch Arizona into the 1959 College World Series championship game against Oklahoma State University in Omaha, Nebraska. He lost, 5-3, letting a 3-2 lead slip away in the seventh inning. This setback would become his greatest baseball regret.

Moving to the pros, Baldwin played for the Philadelphia Phillies, New York Mets and Houston Astros organizations. For five nondescript seasons, he made baseball stops in Williamsport, Buffalo, Chattanooga, Dallas-Fort Worth, Durham, Burlington and Hawaii, getting released several times. He didn’t look like big-league material. The baseball clock was ticking on him.

Along the way, Baldwin married Diane Denoskey, the X-ray technician for the Williamsport team physician. They divorced 11 years later in 1974, at the same time he retired from pro baseball.

Discipline was never a problem for Baldwin in his quest for the big leagues. Bad arm or not, he kept himself exceedingly fit with a strict daily exercise regimen.

“Dave was the best conditioned I ever saw at 6-foot-2 and 200 pounds,” recalled Al Neiger, a left-handed pitcher and minor-league teammate of Baldwin’s. “I was a 6-foot, 195-pound ‘stocky’ specimen who never came close to the [excessive] wind sprints and 500-plus sit-ups that Dave would do every day.”

Baldwin might have had his biggest success back then at the dinner table, necessitating that rigorous workout schedule. Neiger recalls the two of them sitting down to consume an “all-you-can-eat” meal in a Binghamton, New York, hotel. Baldwin was a painstakingly slow eater. The outcome was one-sided.

“Dave and I started eating about noon,” Neiger said. “I had it after about 1 ½ hours. Dave was still working on the appetizers. I went back to our room to take a nap. Two hours-plus later I woke and went looking for Dave. I found him just getting to the dessert table.”

Following the 1964 season, Baldwin decided more drastic means were necessary to keep going as a pitcher. He previously had tried to incorporate a knuckleball, high leg kick and spitball into his game without appreciable success.

Durham manager Billy Goodman, in releasing him from his Class A team, encouraged Baldwin to keep playing but said he had to come up with a new pitching approach. Goodman might have been no more than patronizing or overly polite, but Baldwin took the advice to heart, headed for home and “the box,” and started experimenting with his pitching angle to lessen the stress on his arm.

“He was a smart guy, obviously; very, very bright,” said French, who also caught Baldwin when they played together for Triple-A Hawaii.

Said Neiger, who spent five seasons with Baldwin in the minors, “I do remember his always positive attitude and general cheerfulness.”

Added Baldwin, “Things weren’t working for me. I had to do something.”

He came up with 1) a side-arm fastball, delivered at a 3 o’clock angle with plenty of sink on it; 2) a submarine curveball that he threw in a big, sweeping motion; and 3) an occasional changeup to mix things up.

There was some risk involved, based purely on baseball style points. In the 1960s, most big-league pitchers threw overhand or three-quarters. Anyone who used a lower angle was considered damaged goods by baseball management and usually run off. Ted Abernathy was the notable exception, the only true submariner at the time who was stationed at the game’s highest level. For Baldwin, becoming part side-armer and part submariner gave him a chance.

Within two years, Baldwin was a September 1966 call-up for the Senators, joining a team managed by Gil Hodges, someone with no built-in bias toward pitchers with a side-arm motion or lower. In fact, Hodges welcomed these guys.

In his big-league debut against the Detroit Tigers, on September 6, Baldwin retired the first batter he faced, Jake Wood, on a groundout to first, and got through two scoreless innings, a career enhancer for sure. He pitched in four games during that 1966 call-up, pitching well enough to get invited back and spend most of the next three seasons with Washington.

“If it hadn’t been for Hodges, I would have died in Triple-A,” Baldwin said. “He wanted side-armers. He had three in his bullpen (Darold Knowles and Casey Cox were the others).”

Baldwin’s first big-league pitching victory proved as unorthodox as his low-gravity throwing motion. On August 9, 1967, he pitched the 18th, 19th and 20th innings to close out a 9-7 decision over the Minnesota Twins in a game that concluded just before 2 a.m. in Minneapolis.

Late-night, or more accurately early-morning, appearances were standard fare for the Senators and Baldwin that season. Two months earlier, he had pitched 3 2/3 scoreless frames of an exhaustive 22-inning, 6-5 victory over the Chicago White Sox that finished just before 3 a.m. at home; Baldwin left for a pinch-hitter after throwing the 19th inning. The week before that one, Baldwin had pitched 2 2/3 scoreless innings of a 19-inning game in Baltimore, getting pulled for a pinch-hitter after finishing up the ninth inning of an eventual 7-5 defeat.

Baldwin threw predominantly to right-handed batters. His sinker had people hacking at their feet. His side-arm pitch had guys guessing at it because they were unable to see the total flight of the pitch without turning all the way around and abandoning their batting stance. Lefties, on the other, could get a full view of this sweeping curve coming in and sit on it, lessening its potency. Baldwin was at his best in small doses.

French, the longtime Senators catcher, said Baldwin’s troubles often stemmed from telegraphing pitches, which was unavoidable. “Dave had pretty good control,” French said. “The problem with a submariner/side-armer is it’s pretty darn hard to throw a breaking ball with a submarine delivery. You have to throw it side-arm. If a pitcher is coming submarine, you pretty much know it’s going to be a fastball.”

By playing in the nation’s capital, Baldwin was afforded the chance to chat up a number of high-profile politicians who visited the ballpark. Among them were Vice President Hubert Humphrey, U.S. Senator George McGovern, U.S. Senator Eugene McCarthy, U.S. Representative Mo Udall and a certain president headed for a Watergate scandal a few years later. Nixon, after watching Baldwin close out a game with a scoreless ninth inning, came down to the dugout and when introduced to him absentmindedly asked Baldwin who he was, prompting the pitcher’s aforementioned quip referencing his creative throwing motion.

Baseball royalty also showed up in Washington in the form of Hall of Famer Ted Williams, who became the Senators manager in 1969 and led the team to a satisfying 86-76 season. Williams could be flippant and direct, but was never unbearable with his dugout direction. The former Red Sox great was an acquired taste for many players, but Baldwin always felt comfortable around him.

“I thought he was a good manager,” Baldwin said. “He knew his limitations. He knew little about handling a pitching staff, so he relied on his coaches for help. Many managers don’t want to admit their own weaknesses.”

For sure, Baldwin could test Williams’ patience at times. While he frustrated some of the game’s more established hitters, the low-slinging reliever struggled against guys with lesser credentials. A prime example was journeyman Ted Uhlaender, who went 6-for-11 against him, blistering Baldwin for a home run and seven runs batted in while playing for the Minnesota Twins.

“Ted Uhlaender just owned me,” Baldwin said of a player who later became a Triple-A teammate of his at Iowa in 1974. “He hit line drives even when I got him out.”

Baldwin also gave up a pair of homers to the light-hitting Rich Rollins, the latter coming on a grand slam for the short-time Seattle Pilots in Sicks’ Stadium, a converted minor-league park that the pitcher casually referred to as an “amusement park.” On August 10, 1969, Baldwin was summoned in the sixth inning, asked to protect an 11-5 lead with a runner on first base, and he struck out the first batter. Repeatedly missing the corners, Baldwin walked three in a row to force in a Seattle run. Up came Rollins, who sent a lazy fly ball to left field, clearing the bases by the slimmest of margins over the 305-foot marker, and helped send the expansionist Pilots to a 16-13 victory.

“Rollins hit essentially what was a pop-up to left field,” Baldwin said. “They’d moved the stands and moved the left-field fence in, and it barely made it over. It was a fastball, a sinker about mid-thigh. He got under it and lofted it. I thought, ‘Oh, my gosh, my career is over.’ Ted Williams was just going crazy. It was my worst inning I ever had pitching, even in kid ball.”

In what almost seemed like cruel punishment, Baldwin was traded in the offseason by Washington … to those same Pilots, and their bandbox ballpark, for pitcher George Brunet. During spring training, the submarine pitcher made a point of approaching Rollins and good-naturedly stating the obvious to his new teammate — that Rollins wouldn’t be hitting his stuff anymore. Things would only get complicated thereafter: No one ended up breaking camp and going to Seattle.

The Pilots were sold during spring training, moved to Milwaukee and were renamed the Brewers. In camp, Baldwin had been instructed to throw overhand again by manager Dave Bristol, and this unexpected mound makeover didn’t go well at all. The veteran pitcher was sent to the Triple-A Portland Beavers to begin the 1970 season.

In Oregon, Baldwin resumed his side-arm and submarine ways, and encountered his strangest, if not most dangerous, baseball moment because of it. He struck out Tucson’s Ossie Blanco on a big-bender curveball, something he had done repeatedly over four minor-league seasons against him, and started walking off the field without showing any reaction.

“For me, Ossie Blanco was a rather easy hitter,” Baldwin said matter of factly.

This time, however, he heard Portland catcher John Felske yell, “Look out!” and he glanced around just in time to see an enraged Blanco charging at him with his bat raised, ready to do some serious damage. Luckily, Felske tackled the crazed opposing player, shoved him into the ground and disarmed him.

Baldwin, indicating he would retire at midseason if he wasn’t back in the big leagues by then, luckily was recalled by Milwaukee. Unfortunately, he injured an ankle covering first base on a grounder by Dick Schofield, left the field on a stretcher and was put him on the disabled list for a month.

In the ensuing offseason, he was sold to Triple-A Hawaii (a place that would become a regular baseball stop-off for him), the Brewers explaining to Baldwin that he didn’t fit with the team’s youth movement. Making matters worse, Baldwin was 37 days shy of having four full years of big-league service and qualifying for a baseball pension, and figured he had missed out.

Baldwin spent the next two seasons at the Triple-A level, presumably with little hope of seeing the majors again. He wore jersey No. 37 thereafter to symbolize his service shortfall. However, the Chicago White Sox in 1973 gave him the ultimate retirement gift: A 37-day call-up, not a day more or less. Baldwin made three relief appearances, securing a $1,500 monthly check for his senior years.

Three men made this happen: Hawaii owner John Quinn, who felt compelled to reward someone who had pitched more for the Islanders than anyone else at the time and was well-liked in Honolulu; White Sox general manager Roland Hemond, who was Quinn’s brother-in-law and apparently open to personnel suggestions from him; and White Sox manager Chuck Tanner, a former minor-league teammate of Baldwin’s with Dallas-Fort Worth and loyal friend.

Three men made this happen: Hawaii owner John Quinn, who felt compelled to reward someone who had pitched more for the Islanders than anyone else at the time and was well-liked in Honolulu; White Sox general manager Roland Hemond, who was Quinn’s brother-in-law and apparently open to personnel suggestions from him; and White Sox manager Chuck Tanner, a former minor-league teammate of Baldwin’s with Dallas-Fort Worth and loyal friend.

On August 7, 1973, Baldwin pitched a scoreless fifth and sixth inning for Chicago, retiring his final batter, Cleveland’s Walt “No Neck” Williams, on a fielder’s choice to third base, making Williams 2-for-11 against him, and Baldwin was done with the majors and Tucson bound.

“When the 37 days were up, I was already packed and ready to go,” he said. “I understood.”

Baldwin, then 36, walked away with a 6-11 big-league record, 164 strikeouts in 224 2/3 innings, 3.08 earned run average, 23 saves and his face on four Topps baseball cards.

In 1974, Baldwin played briefly for Triple-A Iowa before effectively putting away his glove and turning to his cerebral pursuits. Yet he was out of baseball for only a month when the Islanders’ Quinn, after losing a couple pitchers to injury, asked Baldwin to come back one last time for two weeks to bolster his Hawaii bullpen. Fittingly, Baldwin made his final pro baseball appearance in Salt Lake City, throwing two scoreless innings in the midst of a thick dust storm, easily the worst playing conditions he had ever encountered. He struck out the last batter that he faced.

Paying back the Islanders in full, Baldwin finished with a collective 20-24 record and 3.43 ERA in 310 innings and 139 games over five tours of duty in this Triple-A baseball paradise. It was the longest he played for anyone.

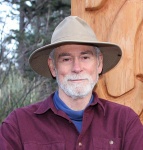

Baldwin returned to Tucson and became a genetics researcher, systems engineer and artist. He had articles published in the Harvard Business Review, American Scientist and other diverse periodicals. Unexpectedly embracing baseball once more, he collaborated with others to study the physics, physiology and psychology of the pitcher/batter confrontation.

In 2011 Baldwin was inducted into the Pima County, Arizona Sports Hall of Fame. That was followed by his induction into the University of Arizona Sports Hall of Fame in 2015.

With his second wife, Burgundy Featherkile, Baldwin retired and relocated to Yachats, Oregon, a sleepy coastal town. He had one of his colorful portraits hung on request in the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. He wrote a memoir titled Snake Jazz, which was baseball slang for curvy pitches. He created his own website.

Baldwin was never one of those players who dwelled on what might have been had he not injured his arm; instead, he marveled about all the good things that happened to him with his baseball career, and he considered himself a fortunate man.

There was never anything wrong with being “the pitcher who threw funny.” It allowed Baldwin to continually beat long odds and on occasion reputable hitters such as Reggie Jackson.

“There was no reason I should have ever made it to the Major Leagues,” Baldwin said.

Sources

In preparing this biography, I relied heavily on a recent interview I conducted with Dave Baldwin, an old interview I held with Baldwin for a 2008 Seattle Post-Intelligencer story that I wrote about him in a “Where Are They Now” format, and recent interviews with Senators teammate Jim French and minor-league teammate Al Neiger. I double-checked Baldwin facts against his 2007 autobiography Snake Jazz. Baldwin’s stats against individual hitters were provided by researcher Dave Smith of Retrosheet.org. Other anecdotal stats were provided by my research or that of Eric Sallee, a Seattle-based SABR member.

Full Name

David George Baldwin

Born

March 30, 1938 at Tucson, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.