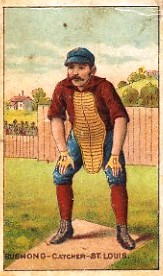

Doc Bushong

A.J. Bushong was better known as Doc or Bush in baseball circles. The Bush nickname is self-explanatory. The doctor reference denotes his degree in dentistry from the University of Pennsylvania. He obtained the degree early in his major-league career but only dabbled at the profession until his baseball career ended nearly a decade later. As a young man, he much preferred the diamond and would barnstorm throughout the country, and even into Cuba, well into the winter rather than devote himself to building a dental practice.

A.J. Bushong was better known as Doc or Bush in baseball circles. The Bush nickname is self-explanatory. The doctor reference denotes his degree in dentistry from the University of Pennsylvania. He obtained the degree early in his major-league career but only dabbled at the profession until his baseball career ended nearly a decade later. As a young man, he much preferred the diamond and would barnstorm throughout the country, and even into Cuba, well into the winter rather than devote himself to building a dental practice.

Though Bushong’s full-time career in baseball was rather short – less than a decade – he built a reputation as one of the finest catchers of the 19th century. Standing 5-feet-11 and weighing 165 pounds, according to the encyclopedias (the Brooklyn Eagle in 1889 described him as 5-feet-8½ and weighing 140 pounds), Bush was among the pioneers behind the plate in calling pitches, crouching, one-handed catching, coaching, and glove/mitt construction. He was highly regarded among the press corps and among his colleagues and fans for his scientific approach to the game. As an intelligent, temperate, and educated man, he was often sought out and cited in the newspapers to help explain the nuances and evolutionary process of the game from the perspective of the backstop.

Bushong played on five league champions in St. Louis and Brooklyn. It perhaps says a good deal about his catching abilities that he couldn’t hit a lick. His career average, .214, resides among the all-time lowest. His flailing with the stick probably looked even worse considering that his finest years were spent catching Bob Caruthers and Dave Foutz, two of the finest hitting pitchers in history. The championship clubs could afford and thrive with a solid backstop at the bottom of the order.

Albert John Bushong was born on September 15, 1856, in Philadelphia to Pennsylvania natives Charles Augustus and Margaret Bushong. The couple had five children: Andrew, born circa 1850; William, 1851; Franklin, 1853; Albert; and Sarah, 1858. The Bushongs moved around the state over the years. In 1850 they resided in Philadelphia. By the end of the decade, they lived in Reading, only to later return to Philadelphia. Charles supported the family by working various jobs such as distiller, clerk, and printer.

Albert attended public schools in Philadelphia, including Central High School, where he graduated in 1876. He played baseball as an amateur in the area with various teams, including the Archer club. While still in high school, Bushong, 18, appeared in one game for the Brooklyn Atlantics of the old National Association, before the formation of the National League. On July 19, 1875, the woeful Atlantics, a club that amassed only a 2-42 record that season, arrived in Philadelphia for a game with the local Athletics; however, only five men made the trip. The Brooklyn club added four Philadelphia amateurs to fill out the roster that day: Bushong, Harry Arundel, Washington Fulmer, and someone known only as Hellings. Bushong caught John Cassidy. An article in the Chicago Tribune said, “The Philadelphia amateurs did the best fielding and batting for the Atlantics.” The backstop went 3-for-5 with a triple, his three hits equaled the hit total of the other amateurs combined. It wasn’t enough; the home team romped to a 23-3 victory.

In 1876, Bushong played for the semipro Brandywine club of West Chester, Pennsylvania. That year, while the Athletics of the new National League were at home between August 12 and 24, Bushong filled in behind the plate in five games. He got one hit in 21-at bats, and when the team played its next league game, two weeks later, he was no longer with the club. In March 1877, Bushong signed with the Mutuals in Janesville, Wisconsin. In May the club joined the League Alliance, a loosely-formed league initially created in conjunction with the National League. It is recognized by some as the game’s first minor league. Two Philadelphians formed the battery, as the club also enticed pitcher Harry Arundel to travel west. At the end of July, 17-year-old Monte Ward, also from Pennsylvania, joined the rotation.

Bushong appeared in every game for the club, occasionally starting in the outfield. At the time, he wore neither a mask nor glove, nor any other protection, for that matter. Janesville faced several National League clubs and fared well. After the Mutuals defeated the Chicago White Stockings on August 17, rumors spread that Chicago owner William Hulbert wished to add Ward and his catcher to the Chicago roster. The Wisconsin State Journal wrote, “The Mutuals are a professional nine, with few equals in the country; they scooped the Chicago White Stockings last week, 5 to 3, and recently beat the Milwaukees for the fifth game, 5 to 4; their pitcher, Ward, is said to be the best in the United States and to have refused very advantageous offers to throw up his present engagement; Bushong, the catcher, is also the best in the country.” The season, however, was a financial disaster for Janesville, “due principally to mismanagement,” and the club disbanded after its September 14-game. Bushong appeared in 42 games and hit a mere .202.

Bushong, Ward, and shortstop Frank Bliss headed east and joined Buffalo of the League Alliance for the last two weeks of the season. The team included another burgeoning 17-year-old pitcher, Larry Corcoran. In mid-October the Janesville Gazette exclaimed, “Mr. A.J. Bushong, formerly catcher of the Mutuals, has signed with the Buffalo club for the season of ’78. We think the Buffalos could not have done better. All who saw Mr. Bushong play here, and compare his playing with the catchers who visited us, acknowledge that he was not surpassed in that position.”

In 1878, Bushong reported to Buffalo, now a member of the International Association. However, he was slated as a substitute player and may never have played a league game for the club. After Buffalo played Utica in the third week of May, Bushong asked for his release to join Utica so he could get more playing time. He stayed with Utica through the end of the season but appeared in only 17 league games. That fall, Bushong entered the dental program at the University of Pennsylvania. He received a DDS in early 1882.

Utica wavered on keeping Bush for the 1879 season, so he joined the Worcester Grays of the minor National Association in March. The club also included another top catcher of the 19th century, Charlie Bennett. Bennett had been a member of Janesville’s main rival, the West End Club of Milwaukee, in 1877. The two backstops caught Worcester’s main hurler, left-handed curveballer Lee Richmond from Brown University. Bushong appeared in 46 games for Worcester and hit a better than normal .290. Worcester manager Frank Bancroft persuaded some of his players to barnstorm during the winter. They headed south with the financial support of Asa Soule of the Hop Bitters Manufacturing Company of Rochester, New York. In late November, the group, which included George Wood, Alonzo Knight, Bennett, Art Whitney, Chub Sullivan, Curry Foley, Bushong, Arthur Irwin, and Tricky Nichols, headed to Cuba. Calling themselves the Hop Bitters, the club became the first American professional team to visit Cuba. Their first game was played in Havana on December 21. The Americans easily won. The trip was a financial flop, though. The men arrived back in New Orleans on December 31 and may have played as few as two games in Cuba.

It doesn’t appear that Bushong spent time in dental school over the winter of 1879-80; he barnstormed with Frank Bancroft into February in New Orleans, Mississippi, and Texas. At times, Bushong opposed the Hop Bitters as a member of the Robert E. Lee club of New Orleans. After returning to the Northeast, he headed to Providence to practice with Lee Richmond. Worcester joined the National League in February 1880, with Bancroft as its manager. Now a full-time major leaguer at the age of 23, Bushong caught 40 games for the Ruby Legs, Bennett 46. Bushong had 25 hits, and a .171 batting average. Richmond performed most of the mound duties, starting 66 of the team’s 85 games. In May a local sportswriter commented, “Bushong’s catching being as good as the best ever seen on the home grounds.” Worcester finished under .500, 40-43 (with two ties), in fifth place. After the season, Bushong resumed his dental studies at the University of Pennsylvania. The Chicago Tribune had an interesting take on the catcher’s endeavor: “When Bush’s teeth are knocked down his throat, he can set them up for himself.”

Bushong and Bennett were in essence holding each other back. They were both superior catchers. The problem was solved in 1881, when Bennett joined Detroit, and they both became full-time National League starters. Bushong caught 76 of Worcester’s 83 games in 1881, leading the league in assists, errors, and double plays. His batting average rose to .233. The team dropped into last place, with a 32-50 record. After the season, Bushong returned to Philadelphia to study. He also barnstormed with the local Burlington club in October and November. Bushong earned his dental degree in early 1882.

Worcester held up the league again in 1882, with an even worse record, 18-66. Bushong caught 69 games. The year saw the rise of a rival major league, the American Association. With the competition, the National League decided to cut its two weakest members, Troy and Worcester. Both clubs drew from inadequate population bases, and probably shouldn’t have been admitted to the league in the first place. The league corrected a longstanding blunder and readmitted teams from New York City and Philadelphia. The news that Worcester would be dropped in 1883 came by midsummer of ’82, and attendance for the lame-duck franchise plummeted. The last home game, on September 29, drew fewer than two dozen fans. With old barnstorming colleague Frank Bancroft slated to manage Cleveland in 1883, Bushong signed with that club in October. He caught 63 of 100 games for the fourth-place club, sharing the backstop duties with Fatty Briody. After the season, Bushong headed to Bordeaux, France, to continue his dental education.

No one in Cleveland, or all of baseball for that matter, heard from Bushong as the season approached. Most assumed that he wouldn’t play in 1884 or perhaps any more at all. Henry Lucas, the man behind the upstart Union Association, was trying to lure as much established talent into his would-be major league as possible. One of his targets was Bushong. In January, he fired off cables to France offering a significant raise if the catcher would join his new St. Louis team. Whether Lucas actually located Bushong and communicated with him is left to conjecture. Lucas claimed he did, but that might merely be a little white lie to conjure up a few headlines for the new enterprise and help him attract better talent. In late February, the St. Louis Union Organ said, “Bushong writes from Bordeaux, France, to a friend, that he does not think he will return to the diamond again, and if he does it will not be with the Clevelands, but with the club that offered the largest inducements.” In all likelihood this was a little propaganda spread by Lucas, who was also trying to land Bushong’s old batterymate Monte Ward.

Bushong finally sent a cable to Cleveland officials on April 2 accepting their contract offer. He hoped to arrive back home before the season started on May 1 and promised to work out aboard the ship. (In the end, he didn’t leave Bordeaux until the 20th.) After hearing that Bushong would return, the Cleveland Herald wrote, “Bushong is not only one of the most honorable men who ever played baseball, but he is also one of the most reliable catchers that ever donned a mask. We congratulate the Cleveland directors, for they have secured a prize.” Bushong met the club in Providence on May 6 but had a little business to attend to. He was married that day to Theresa Gottry, a New York native five years his junior. Once again, Bushong was the main catcher for Cleveland in 1884, working 62 games to Briody’s 42.

The Cleveland club was hit hard that year. First, the team performed poorly on the field, finishing in seventh place under manager Charlie Hackett. Second, and not unrelated, the team suffered financially. With the upstart Union Association, there were more than 30 teams performing in three major leagues. The toll was felt by all. The Cleveland team went on the block. Henry Lucas, the founder of the Union Association, agreed to purchase the club and made a down payment. Hackett had already agreed to manage the Brooklyn Bridegrooms of the American Association, and before Lucas could secure his franchise, Hackett persuaded seven men (Bushong, John Harkins, Pete Hotaling, Bill Krieg, Bill Phillips, George Pinkney, and Germany Smith) to sign with Brooklyn. Uproar followed. It wasn’t the first tampering between the leagues but it was clearly in violation of the spirit of the accord between the leagues. The rift wasn’t mended until the National Agreement, the accord between signing leagues, was revised.

On January 3, 1885, Brooklyn transferred Bushong to the St. Louis Browns of the American Association; the Bridegrooms apparently had enough catchers (in fact using nine of them that year). Brooklyn owner Charlie Byrne may have been rewarding Chris von der Ahe, the Browns’ owner, for support in pushing the controversial signings through. Byrne later regretted the deal as Bushong soon developed the reputation as perhaps the top catcher in the game, helping drive St. Louis to three consecutive pennants. Bushong worked behind the plate in 85 games as St. Louis took first place with a 79-33 win-loss record behind the mound work of Bob Caruthers and Dave Foutz. Bushong led all catchers in games, putouts, and assists. In the postseason series, the second 19th century World Series, against the Chicago White Stockings of the National League the teams tied, three victories apiece with one tie. Bushong went 2-for-13 in four games.

Sporting Life reported in September, “Bushong will, in all probability, make St. Louis his home this winter. He has a good practice among those who know him here as a dentist, and makes quite considerable at his profession.” He also made quite a few friends on the club and spent a part of each winter he was with St. Louis hunting with manager Charles Comiskey and several teammates. In November and December, Bushong joined members of the New York National League and St. Louis American Association teams on a barnstorming tour in the South, mainly in New Orleans. Bushong and Caruthers then sailed for Paris, threatening to hold out from the club if their salaries weren’t raised. Like many players, they were irate over the instituted salary cap of $2,000. Initially, von der Ahe dismissed the tantrum, convinced that they had never actually left the country. In fact, they did. Bushong signed after trading a few telegrams with von der Ahe but Caruthers stuck to his guns. He proved much harder to sign, gaining the nickname Parisian Bob.

St. Louis won the American Association pennant again in 1886. Bushong solidified his reputation behind the plate, catching 106 games for the champions. Foutz and Caruthers won 71 games between them. The team posted a 93-46 record, 12 games ahead of second-place Pittsburgh. Baseball men around the league noticed Bushong’s contributions. For example, the Brooklyn Eagle exclaimed in May, “Bushong is certainly a wonderful catcher. He officiated in two games last Sunday – eighteen innings and three pitchers, and not a passed ball.” Sporting Life noted in September, “The visitors at Sportsman’s Park have wondered at the marvelous work performed of late by Dr. Bushong. Foul tips and wild pitches have been handled with the greatest of ease by the great backstop, and he has been lining the ball down to second in beautiful shape, his throwing of last Sunday being the finest ever witnessed in St. Louis or anywhere else.”

On June 3 in Baltimore, Bushong and teammate Arlie Latham, the Browns’ third baseman, scuffled on the bench. Bushong got in a blow to the face before they were separated. At a special meeting of the Association on the 9th in Columbus, Ohio, president Wheeler Wyckoff suspended the pair for 30 days. Team owner von der Ahe accused the Browns’ rivals of trying to skew the pennant race; he suggested a fine instead. Wyckoff accepted a $100 fine each in lieu of the suspension plus letters of apology from both participants. His offer was readily accepted.

Despite the fact that Bushong was the aggressor, Sporting Life took his side: “It was unfortunate for Bushong that he allowed himself to be provoked by Latham into an open fight on the Baltimore grounds. He is a gentleman by education and instinct and could hardly help resenting Latham’s vile language. … It would have been well had the Association made a distinction between the gentleman and the blackguard and fined the latter about five times as much as the former.”

The Browns faced Chicago again in the World Series. This time a winner emerged, St. Louis, 4 games to 2. Bushong caught every game but as usual produced little at the plate, going 3-for-16. He was at bat when the winning run scored in Game Six. Curt Welch stole home as John Clarkson threw a pitch wide of catcher King Kelly. The winning run was dubbed the $15,000 Slide in recognition of the winner-take-all agreement between the clubs. The Missouri Pacific Railroad honored several of the St. Louis players by naming several of its stops in their honor. Bushong, Kansas (formerly Weeks), is the only one still named as such. The town, a 0.2-square-mile agricultural trading center, was listed with a population of 55 in the 2000 U.S. Census. Bushong the ballplayer continued to barnstorm through November. After working hard all season without an injury, he ironically had a fingernail knocked off in the last exhibition game of the tour.

The American Association expanded its schedule in 1886 from approximately 110 games the previous year to about 140 (Teams in those days seldom played a full schedule). Bushong caught 106 games, the first major-league catcher behind the bat for more than 100 games. He led the league in games, putouts, double plays, and fielding average. The totals for double plays, 14, and putouts, 647, are American Association records. The putouts were also the most by any catcher during the 19th century.

During the American Association’s strongest seasons, Bushong was the best catcher in the league. Many contemporaries considered him the best in the game. Even the leading newspaper from rival Brooklyn, the Eagle, acknowledged: “His work for the Browns was truly remarkable. As a backstop, thrower, and coacher of young pitchers he had perhaps no equal in the profession. It is generally admitted that he made Caruthers, Foutz, (Nat) Hudson, and (Silver) King what they are, professionally speaking, and no catcher ever did better work than Bushong did in 1885, 1886, and 1887.” The St. Louis men concurred. Von der Ahe later called Bushong “one of the most intelligent and gentlemanly men (I’ve) ever met – either as a ballplayer or outside of that profession.” Browns manager Comiskey said Bush was “one of the gamest catchers I ever saw, one who never knew when he was beaten, or hurt either, for that matter. … Foutz says Doc Bushong was the best catcher to help a pitcher that ever stood behind a plate.”

Bushong played during a crucial developmental stage for backstops. He was among the pioneers in several aspects. For one, he was among the first, if not the first, to crouch behind the plate, as opposed to the catchers’ stooped stance of that day. He also gave the signs, a controversial subject at the time. The Portsmouth Daily Times said of his signaling, “He held his hands out with his palms together and moved them back and forth in this way: By holding them on a line with the outside corner of the plate he gave a sign for a curve; with his hands on a line with the inside corner of a plate he called for an in-shoot, and by putting them behind the center of the rubber he asked for a fast one right over.” Bushong explained his catching philosophy: “A catcher’s position has much to do with his effectiveness. He should stand firm, and move around just as little as possible. Some catchers, in waiting for the ball from the pitcher, generally rest their hands on their knees and wait in that position. I find by experience that that is a mistaken policy. I stand with my hands extended directly in front of me. I can follow the course of the ball and catch it much easier.”

But Bushong was slow to adapt in certain areas. In 1888 he was still wearing his chest protector beneath his uniform, one of the last catchers to do so. Most had taken to the outside protector by the middle of the decade. Bushong at first rejected using a glove when they came into vogue in the 1870s. However, when he did start wearing a glove, he did so wholeheartedly. He put considerable effort into maintaining his gloves, constantly mending, adjusting and fortifying them. Said Sporting Life in 1890, “He will never get new gloves, and prefers to patch up the old ones until they are almost a bundle of rags.”

Bushong was looking ahead; he wanted to protect his hands. Though he wouldn’t dive full time into dentistry until he could no longer play ball at a top level, he knew the day was coming. As was the case with all catchers, his hands were beaten up over the years. He said, “I have learned that in receiving a right-handed pitcher I get all the balls on my left hand. With a left-handed pitcher it is just the reverse, and I get all the balls on my right hand. As we catch more right-handed pitchers than left-handers, our catchers’ left hands are generally pretty well battered out of shape.” After leaving Cleveland and lefty Lee Richmond, Bushong almost exclusively caught right-handers. This helped protect his right hand. He padded the other the best he could with sponges. As one journalist put it, he wore “a conglomeration of ragged buckskin, string, sponges, and cloth.” Bushong was right-handed, so he couldn’t pad that glove excessively as it might interfere with his throws. Therefore, he took a rather large leap – pioneering one-handed catching by at least 1886, as noted in Peter Morris’s comprehensive work Catcher. Bushong at least made inroads along these lines; in the days before modern mitts, consistently catching one-handed was, of course, impossible. The objective was more to trap the ball with the hand against the body or ground. Though he didn’t spark a movement, as Randy Hundley and Johnny Bench later did, he took more steps than others to protect his right hand.

One newspaper declared in 1892, “After catching for ten years, Bushong had a pair of hands as delicate and trim as those of the average dry goods salesman. There were no notches, twist, or serpentine twirls about his hands.” This wasn’t exactly the case. It was a tough era and every catcher’s hands took a beating. A drawing that accompanied an 1888 interview depicted his left hand gnarled and beaten up. He took measures to protect it, though. A newspaper wire story in 1889 declared, “Catcher Bushong of the Brooklyns has had a mitten made for his left hand which greatly resembles a small-sized pillow.” This was probably the source for a New York Times declaration in 1915: “Doc Bushong, the famous catcher of the old St. Louis Browns, was very careful about his fingers, as he intended practicing dentistry after his days as a ballplayer were over. He wore the largest glove he could find, and had added pads until it looked like a pillow. The Doctor was proud of this affair, and would not allow anyone to use it. Out of Bushong’s idea grew the idea of the mitt.” Morris in Catcher wrote that the development of the catcher’s mitt is more complicated than that but that perhaps Bushong’s efforts show an evolutionary link between early leather gloves and modern mitts.

St. Louis won another championship in 1887 with a stellar 95-40 record. The season proceeded as the first two had – Bushong catching Foutz and Caruthers most of the games. On July 1 though, he broke his finger. “Bushong’s fingers were mashed by a wildly-pitched ball in the Louisville-St. Louis game yesterday,” the Baltimore Sun reported on July 2. He later offered this odd perspective on the injury: “I think that every man that plays ball ought to wear hair on his upper lip – that is if he can raise it. I am positive that the shaving of the upper lip is a big drawback to a man’s sight. I have watched the thing closely, and I am sure that I am right. Take my case, for instance. When I shave my upper lip it always makes my eyes discharge more or less water and a man can’t see in such a condition. The day that I had my finger broken in Louisville by a pitched ball I had no moustache. It had been taken off the day before, and I truly believe that this alone was the cause of the accident. I am an advocate of hairy lips in the profession.” The balding Bushong was indeed attached to his facial hair.

Jack Boyle stepped up and essentially took Bushong’s job. He caught more than 40 games in a row, a remarkable feat for the era. Bushong didn’t rejoin the club until August 14; even then he played the outfield. Boyle finally was too sore to cover behind the plate, but Bushong wasn’t ready to return. Others had to cover for a few games. Bush caught again for the first time on September 18. The Browns faced Detroit in the World Series, an extended affair. The Wolverines won, 10 games to 5. Bushong caught nine of the 15 games, going 7-for-29. He wasn’t the only one injured in 1887. Earlier in the year, he challenged another player with a rocket arm, third baseman Arlie Latham, his old sparring partner, to a throwing contest. Manager Charlie Comiskey put up $100 to make things interesting. Latham didn’t warm up. He won on his first toss, but his arm was forever damaged. His strong arm was once his pride; soon it would be his ridicule.

Bushong and others barnstormed through the winter in New Orleans, eventually landing in California and playing into the new year. While Comiskey and the boys were away, von der Ahe sold off a good portion of his club in late November. Curt Welch and Bill Gleason were shipped to Philadelphia for three players and $3,000. The heart of the Browns’ battery was sold to Brooklyn: Foutz (for $5,500), Caruthers ($8,500), and Bushong ($4,500). von der Ahe, seeking to justify his actions, said, “Bushong has acted as though he cared little for the success of the team.” The owner also accused the catcher of being jealous of Jack Boyle. Sporting Life saw additional motives behind the move, asserting that Bushong’s arm was becoming more and more inaccurate; his best days were behind him (he was now 31 years old); his tentativeness at bat after a beaning left his stick even less effective than usual; and the rise of Jack Boyle made him expendable. Sporting Life didn’t say, but the underlying motive was more probably pecuniary. Von der Ahe often battled family, lawyers, business partners, and employees over finances. His abundant legal troubles were fodder for the local papers. He also had expensive tastes, including a string of young mistresses. After securing the funds from Philadelphia and Brooklyn, he took an extended vacation, leaving an irate Comiskey to rework the franchise.

Bushong returned to St. Louis from the West Coast in January 1888, sold his home and established a residence in Brooklyn, where he lived the rest of his life. Bushong played in 69 games for the Bridegrooms, catching his two old St. Louis battery mates Foutz and Caruthers, plus Adonis Terry, Mickey Hughes, and Al Mays. The Bridegrooms battled St. Louis for the pennant. In July they ran neck and neck. Much to Chris von der Ahe’s dismay, the former Browns were hailed upon their return to St. Louis on July 6. “Foutz, Caruthers, and Bushong met their old friends on the St. Louis club for the first time this season in St. Louis, and they were welcomed by a parade of about twenty carriages and a brass band.” the Baltimore Sun reported on July 7. Soon thereafter sparks flew between the franchises. Bushong wrote an ill-advised letter to Tip O’Neill, the Browns’ slugger, encouraging O’Neill to tank his performance in a coming series and gain his release from the Browns. After he did so, Brooklyn would then offer him a lucrative contract. The letter was penned at the behest of Bridegrooms minority owner Frederick Abell.

Von der Ahe hit the roof when he found out. He accused Brooklyn of tampering but instead of Bushong and Abell, he focused his blame on club president Charlie Byrne. The issue helped fuel an extended rivalry between the two clubs and their owners. von der Ahe also went after his own men, suspending O’Neill for a weak performance and fining Silver King for blowing a 4-1 lead on July 10. For his part, O’Neill blamed his poor play on dysentery. Fanning the flames, Byrne asked von der Ahe for terms on O’Neill. The American Association held a special meeting in Philadelphia on August 7 to resolve the matter. After the hubbub, Brooklyn was merely reprimanded for tampering. St. Louis proved to be the stronger club in 1888 despite the loss of the five men. King and Nat Hudson stepped up to carry the workload on the mound, collecting 70 of the club’s 92 victories. Brooklyn finished in second place, 6½ games behind.

Over the winter, Bushong didn’t practice dentistry, preferring to take the time off. He and Adonis Terry rode bicycles to keep in shape. In the spring, they talked manager Bill McGunnigle into working the men out on bikes, though few of the players took to the new exercise. By 1889, Bushong, at 32, was among the oldest men in the league, and he began coaching the pitchers and catchers as much as playing. He appeared in only 25 games for Brooklyn, backing up Bob Clark and Joe Visner. On July 4 in the second game of a doubleheader in St. Louis, Bushong injured his arm and played in only two more games during the regular season. The injury marked the beginning of the end of his career in baseball. After the game on August 24, the Brooklyn Eagle wrote, somewhat paradoxically, “Al Bushong gave about as yellow an exhibition of catching as has been seen at the Cincinnati park this season. For one of the Reds to reach first base was as good as two, ‘Bush’ being powerless to stop them. Although he made five attempts to catch men going to second, his throwing was very bad. He nailed no less than three men at third base, however, and his fine work with the stick helped not a little to pull out the game.”

Despite his idleness, Bushong remained with the club during home stands. He didn’t travel with the club. He umpired on the bases on July 20, a 3-2 loss to Philadelphia. He also umpired an entire three-game series against Kansas City on August 30 and 31. The Bridegrooms won each game by a significant margin: 14-4; 11-4; 8-2. Entering the August 30 game, Brooklyn was 2½ games behind St. Louis. With those three victories plus two St. Louis losses, the two clubs sat tied at the top of the leader board to kick off September. On September 5, St. Louis was two games behind. Irate, von der Ahe filed a protest because Bushong had umpired those three crucial games against Kansas City. It was merely a desperate effort; after four straight pennants, von der Ahe had come to believe the championship belonged to him. The rules permitted the team captains to select an umpire prior to a contest. It was all aboveboard and, in fact, not uncommon. Besides, Kansas City lost by 10, 7, and 6 runs. They were not particularly close affairs. The protest would not be von der Ahe’s last.

The Bridegrooms finally edged St. Louis for the pennant, by two games. Von der Ahe didn’t take the loss gracefully. He accused Columbus shortstop Charlie Marr, a lefty, of throwing the final game of the season on October 14 to Brooklyn, a 6-1 loss. Marr’s sin was committing four errors. Von der Ahe further charged the Brooklyn franchise with crookedness. Al Spink, a biased Browns’ fan and publisher of the locally produced The Sporting News, chimed in and blasted the Brooklyn franchise as well for its heavy-handedness, and even charged the club with bribery and fraud. The two major gripes involved Bushong. Owner Byrne had sent Bush to Cincinnati to encourage the Reds, long out of the pennant race, to give it their best against St. Louis on their final day of the season, October 15. Spink wrote, “Bushong the Brooklyn catcher, offered (Cincinnati pitcher Jesse Duryea and catcher Jim Keenan) $100 each to win the decided St. Louis-Cincinnati game, and handed the money over after the success had followed their efforts. President Byrne furnished the bribe.” This was a common occurrence in early baseball, an inducement to play hard and defeat a pennant contender. Game-fixing wasn’t involved but the questionable nature of the gesture eventually led to its banishment – decades later.

In November, von der Ahe had team representative J.J. O’Neill issue the following statement: “The Brooklyn club had resorted to methods that we believed were dishonorable, and if they had remained in the organization, we had intended to prefer charges of indirect bribery. We have a telegram sent by A.J. Bushong to (St. Louis catcher) John Milligan, offering Milligan money.” The letter read, “Brooklyn, Oct. 19. – John Milligan, Catcher St. Louis Base Ball Club: — Friend Jack. – Hope you will answer the telegram I sent you, which was that I will give you a check for $200 for your share in our agreement. It will be a personal favor to me if you will, and besides will be a sure thing for you and yet give me a chance to make a little. Don’t lose your chance as you did with (Tommy) Tucker. Reply immediately, at my expense. A.J. Bushong.” Von der Ahe gave no context to the letter and was pushing its supposed crookedness, an angle he knew didn’t exist. Not only did he embarrass Bushong but his own player, Milligan, as well. (Sporting Life wrote, “It was learned that the Tucker matter in Bushong’s telegram referred to an agreement made between Milligan and [Tommy] Tucker, of the Baltimore team, to divide equally a prize of $250, offered by a chewing gum firm for the leading batsman of the American Association, no matter which one of them should win the prize.”)

The agreement between Bushong and Milligan (and between Bushong and Tucker) was a hedging of bets. With the two clubs battling for the pennant, the pair agreed that whichever one made the World Series, half the anticipated earnings, which they guessed would be about $200 to $250, would go to the other. In this way, they each accepted a half payday rather than risk an all-or-nothing shot. This was also not new in sporting circles. Similar agreements were made for decades in baseball, sometimes publicly, sometimes not. In the Series, the New York Giants defeated the Bridegrooms, six games to three. Bushong, with big-game experience, returned to the lineup and caught three games, going hitless in eight at-bats.

Over the winter, Bushong played indoor baseball, a growing fad that began in Chicago. More significantly, the Brooklyn franchise switched leagues and moved into the National League for the 1890 season. After winning the American Association pennant in 1889, the Bridegrooms won the National League championship in ’90, an achievement never equaled. Once again, Bushong played little, catching in only 15 games, despite holding a roster spot the entire season. He also appeared in two World Series contests against Louisville. The clubs tied with three victories apiece (they played one tie). With those contests, Bush’s major-league career ended. He had appeared in 672 games, catching in all but four of them. He finished with a meager .214 batting average, getting only 73 extra-base hits (two home runs) in 2,397 at-bats. His career average resides among the lowest for major leaguers with at least 2,000 at-bats. Not surprisingly, the list contains quite a few catchers.

The raw numbers for games caught pales in comparison to those put up today, so a little perspective is needed. First, Bushong was exclusively a catcher. Some men typically thought to have put up a more significant career behind the plate during the 19th century, including King Kelly and Buck Ewing, were in fact just part-time catchers. Only Charlie Bennett caught more games than Bushong did in the majors during the 1880s, 664 to 647. Bushong falls fourth on the list of games caught prior to 1890 with 653, behind Pop Snyder (861), Silver Flint (743), and Bennett (699).

Hedging for the 1891 season, the Bridegrooms didn’t officially release Bushong until March 26. On April 8, he signed with Syracuse of the Eastern Association. He was released by Syracuse on May 26 and immediately signed with Lebanon, Pennsylvania, of the same league, playing with the club through mid-July. He was actually released twice by Lebanon. The Brooklyn Eagle noted after his final departure, “Catcher Bushong has been again released from the latest minor-league team he had joined. Cause – salary too high for the club’s receipts.” In all, he appeared in 29 games in the Eastern Association, batting only .160 with no extra-base hits. In his last professional game, on July 9 (a 4-3 win over Syracuse), Bushong caught Joe Fitzgerald, placing one hit in four at-bats.

Soon after his release, the Eastern Association hired Bushong as an umpire. He had umpired 12 major-league games between 1880 and 1890 and also worked some exhibition contests. By the end of August, Bushong was home in Brooklyn with his family. But not before a little drama on August 8, as Sporting Life reported: “At Albany last Saturday, the 8th, Umpire Bushong had a narrow escape from being mobbed at the close of the game between the Buffalo and Albany clubs. His decisions were bad and throughout the game there was no end of growling from the players of both teams. It was a critical game for Albany as the local team was tied with Syracuse for second place in the race. In the ninth inning the last man had been no sooner declared out, with Buffalo the winner, than the howling mob made a rush for Bushong. In an instant he was surrounded. Then the ballplayers hastened to his rescue, and while the police force at the grounds tried to keep the thoroughly aroused ball cranks back, the march to the dressing room began. The police were obliged to use force, striking promiscuously in the crowd. At last the rooms were reached, and it was nearly ten minutes before the mob stopped trying to force their way in.”

Bushong finally had time to dive full force into his dental career. He worked at a large dental house in Hoboken, New Jersey, eventually becoming manager of the facility. His brothers and sons worked there as well. Concurrently, he also developed a large practice in his hometown, Brooklyn. On the side, he loved to bowl and was regularly cited in Brooklyn newspapers for his accomplishments on the lanes from at least 1888 throughout the 1890s.

The Bushongs settled at 423 Tenth Street in Brooklyn. They had seven children: Stewart, born in 1885; Alice, 1886; Charles, 1888; Beatrice, 1890; William, 1892; Mary, 1899; and John, 1895. John died a horrible death when he was 3 years old on the night of Election Day in November 1898. He strayed too close to a bonfire. His clothes caught fire and death soon followed. The other three sons, Stewart, Charles, and William, all became dentists. On August 19, 1908, Albert Bushong died of cancer at his home at the age of 51. He was interred at Holy Cross Cemetery in Brooklyn.

Sources

Thanks to Baseball-fever.com for verifying some data.

Ancestry.com.

Ashwill, Gary, Agate Type website.

Atchison Daily Globe, Kansas, 1888.

Ball, David, The Nineteenth Century Transaction Register, SABR.

Baltimore Sun, 1887-91.

Baseball-reference.com.

Bismarck Daily Tribune, North Dakota, 1887.

Boston Daily Advertiser, 1876.

Boston Globe, 1879, ’82, ’86, ’91, 1908.

Brooklyn Eagle, 1885-98.

Cash, Jon David. Before They Were Cardinals: Major League Baseball in Nineteenth-Century St. Louis. St. Louis: University of St. Louis Press, 2002.

Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette, Iowa, 1887.

Chicago Tribune, 1875-91, 1908-09.

Cincinnati Enquirer, 1884.

Cleveland Herald, 1883-84.

Daily Inter Ocean, Chicago, 1877, ’80, ’87, ’90-91.

Daily Picayune, New Orleans, 1887.

Decatur Saturday Herald, Illinois, 1890.

Dewey, Donald, and Nicholas Acocella. Total Ballclubs: The Ultimate Book of Baseball Teams. Wilmington, DE: Sports Media Publishing, Inc., 2005.

Egan, James M. Jr. Baseball on the Western Reserve: The Early Game in Cleveland and Northeast Ohio, Year by Year and Town by Town 1865-1900. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2008.

Familysearch.com.

Fitchburg Sentinel, Massachusetts, 1890.

Frederick News, Maryland, 1887.

Hetrick, J. Thomas. Chris von der Ahe and the St. Louis Browns. Lanham, Maryland: Rowan and Littlefield, 1999.

Janesville Gazette, Wisconsin, 1877-87, ’92, ’98

Logansport Journal, Indiana, 1888, ’92.

Logansport Pharos, Indiana, 1886.

Lowell Daily Citizen, Massachusetts, 1878-79.

Milwaukee Journal, 1885.

Milwaukee Sentinel, 1877, ’84, ’87.

Morris, Peter. A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball, The Game on the Field. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006.

_____. Catcher: How the Man Behind the Plate Became an American Folk Hero. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2009.

Nemec, David. The Beer and Whiskey League: The Illustrated History of the American Association — Baseball’s Renegade Major League. New York: Lyons and Buford, Publishers, 1994.

Newark Daily Advocate, Ohio, 1886.

New York Times, 1875, ’85-86, 1908, ’15.

Outing, 1886.

Pearson, Daniel Merle. Baseball in 1889: Players vs. Owners. Madison, Wisconsin: Popular Press, 1993.

Piqua Daily Call, Ohio, 1886.

Pittsburg Post, 1889.

Portsmouth Daily Times, Ohio, 1896.

Retrosheet.org.

Rocky Mountain News, Denver, 1886, ’89.

San Francisco Examiner, 1887.

Sporting Life, 1885-91, ’96, ’98, 1905, ’08.

The Sporting News, 1889.

St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 1881-87.

St. Louis News, 1889.

St. Louis Union Organ, 1884.

Syracuse Evening Herald, 1891.

Syracuse Herald, 1882, ’89.

Tiemann, Robert L. and Mark Rucker. Nineteenth Century Stars. Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1989.

Washington Post, 1891, ’96, 1908.

Wikipedia.org.

Wisconsin State Journal, Madison, 1877.

Wright, Marshall D. The International League: Year-by-Year Statistics, 1884-1953. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1998.

Full Name

Albert John Bushong

Born

September 15, 1856 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

August 19, 1908 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.