Don Bradey

Don Bradey’s professional baseball career spanned 15 seasons—a career that saw him travel the country, with stops in Colorado Springs, Memphis, Waterloo, Syracuse, New Orleans, Little Rock, Durham, Oklahoma City, San Antonio, Amarillo, and Charlotte. But it was during his 12th season that Don was elevated to major-league status with the Houston Colt .45s. Although he pitched in only three games—for a total of 2 1/3 innings—during the ten days he was in the majors, Bradey started the last game the Colt .45s ever played; was at the close of mosquito-infested Colt Stadium; played in both Candlestick Park in San Francisco and Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles; roomed with future Hall of Famer Nellie Fox; and pitched to many baseball greats from the 1950s and ’60s, like Willie Mays, Duke Snider, Orlando Cepeda and Maury Wills.

Don Bradey’s professional baseball career spanned 15 seasons—a career that saw him travel the country, with stops in Colorado Springs, Memphis, Waterloo, Syracuse, New Orleans, Little Rock, Durham, Oklahoma City, San Antonio, Amarillo, and Charlotte. But it was during his 12th season that Don was elevated to major-league status with the Houston Colt .45s. Although he pitched in only three games—for a total of 2 1/3 innings—during the ten days he was in the majors, Bradey started the last game the Colt .45s ever played; was at the close of mosquito-infested Colt Stadium; played in both Candlestick Park in San Francisco and Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles; roomed with future Hall of Famer Nellie Fox; and pitched to many baseball greats from the 1950s and ’60s, like Willie Mays, Duke Snider, Orlando Cepeda and Maury Wills.

Donald Eugene Bradey was born on October 4, 1934, in Charlotte, North Carolina, to Roy Lee and Agnes (Barrett) Brady. He was the third of four brothers. (The others were John, Raymond, and Ken.) His parents both worked for the Highland Park Manufacturing Company, a textile firm, for many years. Roy was a loomfixer while Agnes was a weaver. Roy grew up playing baseball, and pitched on the Victor-Monaghan Company team in Greer, South Carolina. His career ended when he hurt his arm at the age of 18, pitching in two games in the same day.

Don followed in his father’s footsteps, beginning to play baseball, along with other sports, when he was 6 years old. When he reached high school (Charlotte Tech) he first played right field. Then as a sophomore, he began to pitch, while continuing to play right field whenever he wasn’t on the mound. Charlotte Tech was a small school (enrollment of about 250), but the baseball team reached the state playoffs all of his four years, and he earned all-state honors in his last three years. The 5-foot-9, 180-pound right-handed pitcher and batter posted a 23-4 high-school won-loss pitching record while batting .500 in his senior year. His baseball mentors were his father and the coach of Charlotte Tech, Daniel “Doc” Martin. Doc helped Bradey with his fastball, curve, and change-up. Doc was an honest, straight-talking, hard-working teacher in his mid-20s who coached both the baseball and football teams.

Major-league scouts started to follow Bradey during his junior year. He had played the previous summer for a mill team in Maiden, North Carolina, and he caught the eye of scouts in the area, including those from the Pittsburgh Pirates, Washington Senators, and Harry Postove of the Chicago White Sox.

As his senior year started, at the age of 17, Bradey married his high-school sweetheart, Nancy Bracket. They moved in with her parents, and as Bradey later acknowledged, they were basically just kids at the time: “If we did not both have great parents, I don’t know how that would have turned out.”

At the end of his senior season, Bradey accepted tryout offers from the Pirates and White Sox. He and Doc Martin flew to Pittsburgh and he worked out for the Pirates and their general manager Branch Rickey at Forbes Field. In Pittsburgh he saw his first major-league game. Don and Doc then flew to Chicago and worked out for the White Sox and their general manager, Frank Lane, and farm director, John Rigney, at Comiskey Park (throwing to catcher Sherm Lollar). After the tryouts Bradey agreed to sign with the White Sox. Harry Postove, in his second year as a scout for the White Sox, was credited with signing Don.

Bradey’s decision to sign with the White Sox created a lifelong family story. Before the 18-year-old’s signing could be official, the White Sox said, a parent had to sign the contract. Don’s father was back in Charlotte and had never flown in an airplane. On the phone he told Don he would come to Chicago but only by train. So Roy and Don’s oldest brother, John, rode the train to Chicago and signed the contract. The White Sox assigned Don to the Colorado Springs Sky Sox (Western League) and told him to report there within a week. Bradey first wanted to return to Charlotte, where his wife was expecting their first baby. “Dad said he would not fly, so Doc and my brother take my father to a bar, and after a couple drinks, he says he’ll fly home,” Bradey recalled. “We then get on a flight, but bad weather forces the plane to divert to Charleston, West Virginia. After a rough landing and the unplanned layover, we fly on to Charlotte. Dad didn’t say anything during the flight, but when we got off the plane in Charlotte, he turned to me and said, ‘Son, that was my first—and last—flight. You’ll never get me on another plane!’ ”

After a few days back home, Bradey joined the Sky Sox on June 15, 1953. Don says, “It was a whirlwind. It was pretty awesome. I was shy at the time. I was only 18. After I arrived the night before, I remember walking out the door of the hotel the next morning and looking at Pikes Peak, and wow, I had never seen anything like that before, snow on the mountain and all. Then the first person I met was the team’s general manager, Bill MacPhail. He was a real gentleman and made me feel at ease.”

The Sky Sox manager, Don Gutteridge, “was a no-nonsense manager. He liked to cut up, but when it came to play, he was no-nonsense. I thought I was in decent shape when I got there, but in the high altitude (6,035 feet above sea level), I wasn’t. He believed in run, run, run. I got in good shape.” Among Bradey’s teammates were a young Jim Landis, who was making his first mark in professional baseball; catcher Sam Hairston, a former Negro League player, who was voted the Western League’s MVP in 1953; 18-year-old Earl Battey, Hairston’s backup; and fellow rookie Joe Hicks, an outfielder who played for the White Sox’ 1959 pennant winners. Of Landis, Bradey said, “Jim was my roommate, a really good center fielder, a good hitter and really a great guy. We kind of buddied around together as we were about the same age and we had a lot of fun together.” Of Hairston, he commented, “Sam helped me a lot with my pitching. I really worked with him. He was a special person.”

Bradey made his debut on June 17, pitching one inning and giving up a run. On the 23rd the home crowd gave him an ovation when the public-address announcer informed them that he was the father of a baby girl born that day back in Charlotte.

As the end of the season neared, the Sky Sox and the Denver Bears were fighting for the pennant. Because of rainouts the Sky Sox had to play three doubleheaders in the last five days of the season. On the next-to-last day of the season, the Sky Sox won the first game of a doubleheader over the Des Moines Bruins, and a win in the second game would give them at least a tie for the league title. With a worn-out pitching staff, the Colorado Springs Free Press reported, “Between games, Manager Don Gutteridge, in the Skysox clubhouse, proposed a flip of a coin to decide who would pitch the nightcap. ‘Flip, hell,’ said Bradey, ‘Just give me the ball and I’ll take care of the pitching.’ ” He did just that with a four-hit, 7-0 shutout, which the Free Press termed “his greatest game of the season.” The Sky Sox then defeated the Lincoln Chiefs 10-7 the next day to finish in first place. They lost in the first round of the league playoffs. Bradey finished his first professional season with a 5-4 won-loss record and a 3.23 ERA.

At that time most minor-league ballplayers went back home to work, and then waited for a contract to come in the mail and a letter telling them where to report. Bradey didn’t know if he’d be back in Colorado Springs or moved up to another city. But this first offseason started what would become the norm for the next 14 years—returning to Charlotte and working in the mill at his “second” job—a job that was always there as Nancy had a connection to the mill owners. Bradey did everything at the mill through the years: cleaning looms, working in the spinning room and opening room, etc. He did this in all but one year from the fall/winter of 1953 through the fall/winter of 1966.

In 1954 Bradey attended spring training with the White Sox and then was assigned back to Colorado Springs, where Nancy and their baby joined him. But 1954 in Colorado Springs was different than the previous year. Manager Gutteridge was gone, having moved up to Double-A Memphis, and many of the players had moved on as well, including Sam Hairston, Jim Landis and Len Johnston. Bradey said, “It was a team coming, a team going, and a team there. There were three different managers, attendance was way off and we were not very good. Nothing ever jelled.” The team finished 48-104, dead last in eighth place, 47 games behind the Denver Bears. Bradey had a 6-8 record and a 5.88 ERA, pitching 124 innings.

In 1955 Bradey was moved up to Class AA Memphis but after a few weeks was sent back to Colorado Springs, then after a short time was sent to the Class B team in Waterloo, Iowa. Used as a starter and reliever, he ended the season with an overall 4-8 record.

With the demotions in 1955, Bradey felt his tenure with the White Sox organization was likely coming to an end. He was right; in 1956 the White Sox sold his contract to the Detroit Tigers. He spent 1956 with the Syracuse Chiefs of the Eastern League, mainly as a starting pitcher, finishing with a 7-13 record.

In January 1957 the Tigers sold Bradey’s rights to the New York Yankees and the Yankees sent him to their Double-A team in the Southern Association, the New Orleans Pelicans. He spent the next five years playing in the Southern Association. He spent the first three years in New Orleans, the first two as a Yankee affiliate and the final year with no affiliation. Peanuts Lowry was his manager in 1957. Bradey was used as a reliever, finishing with a 10-8 record in 56 games. In 1958, under managers Charlie Silvera and with Ray Yochim, Bradey was used as a reliever again and finished with a 7-9 record in 60 games.

In 1959 the Yankees dropped their affiliation with New Orleans and the Pelicans were unaffiliated. The manager, former Boston Red Sox pitching star Mel Parnell, used him as a starter. Bradey had a good season. He had won 18 games entering the last day of the season, on which the Pelicans were to play a doubleheader. Parnell wanted Bradey to have a chance to win 20 games, so he started Bradey in both games. “I’ll never forget that,” Bradey recalled. “I started the first game—won that by a score of 6-3 over the Mobile Bears. Then I started the second game, pitched five innings, we were behind 6-3 at the time and Parnell takes me out and puts me in left field. I played 3-plus innings out there, and then he had me come back in to pitch the last out in the top of the ninth. Unfortunately, we didn’t win the second game (lost 7-6) and I finished with 19 wins for the season.” Bradey achieved a career high in wins with a 19-14 record.

The team moved to Little Rock in 1960. Fred Hatfield was the manager. Bradey again was used mainly as a starting pitcher and finished with a 17-8 record. The team won the Southern Association playoffs after finishing third in the regular season.

After the season Bradey played winter ball in Panama. It was an experience he would never forget, and one he would only do once. “The Panama National Guard was on the field from the left-field foul line, around home plate to the right-field foul line—all with automatic weapons. We knew no one was coming onto the field. There were about 25,000 fans in attendance for that first game.” This was a time of unrest in Central America and the Caribbean. Castro had just taken over Cuba. There were Panama Canal issues. “We stayed through Christmas. I had the whole family with me, Nancy, Donna and 8-month old Don Jr. Then one day in January, we got a call from a team representative who said ‘could we be ready to leave in two hours,’ and we did. Nancy was tickled to death to get back to this country.” Bradey said he was paid well but he felt unsafe and it was an experience he would not do again.

In 1961 the Little Rock team became affiliated with the Baltimore Orioles. Bradey again was used mainly as a starter and finished with a 12-7 record and a 3.51 ERA. Bradey said he had fond memories of Little Rock, where “the people were nice and very supportive of the team,” but at the end of the season the Southern Association went out of business.

In the offseason of 1961 the brand-new Houston Colt .45s, seeking to stock their roster, purchased Bradey’s contract, along with those of three other players, from Little Rock. Bradey

reported to the team’s spring training camp in Apache Junction, Arizona, and later spent time with the Colt .45s’ minor leaguers in Chandler, Arizona. From spring training he was assigned to the Colt .45s’ Triple-A team in Oklahoma City. But two months into the season, Bradey wasn’t getting along with the team’s manager, Connie Ryan, and Bradey asked Tal Smith, Houston’s farm director, to send him somewhere else. Smith sent Bradey to Durham in the Class B Carolina League. Although Durham was a step down, it was the start of Bradey’s true road to the majors. The manager was Lou Fitzgerald and, said Bradey, “If it wasn’t for Lou, I probably wouldn’t have made it to the majors. He believed in me and he helped my confidence.” Fitzgerald used him as a starter, and he finished the season in Durham with a 10-2 record and a 2.69 ERA.

Heading into the 1963 season Bradey was excited and had high hopes. He had been assigned to the Colt .45s’ new Double-A franchise in San Antonio, managed by Fitzgerald. “Lou wanted me to be a player-coach, but I really wasn’t interested in that, I still hoped to make the majors,” Bradey said. Fitzgerald made him a reliever again, with a few spot starts. “I think they considered me an older pitcher, and they had younger pitchers they wanted to pitch. … But it was a great year. We came together as a team and we won the regular season pennant. Although we lost to Tulsa in the playoffs, it was a good year.” Bradey finished the season with a 4-9 record in 52 games, 88 innings pitched, and a 2.66 ERA. “I did see this guy, that guy go up to the majors. But it didn’t happen with me then, and I just stayed with it,” Bradey said.

In 1964 Bradey was sent again to San Antonio, which won both the pennant and the playoffs. He was picked to play in the Texas League All-Star Game against the Colt .45s, and was the winning pitcher as the All-Stars defeated the Colt .45s, 8-7. “I remember I pitched the last two innings and in the eighth inning, I hung a curve ball and Carroll Hardy hit a home run. I was really upset about that, but we came back in the ninth inning and won. All the guys on the all-star team were really elated because they beat a major-league team.” Bradey was San Antonio’s relief specialist that season with a 12-5 record and a 2.88 ERA. “It’s amazing when you have that confidence,” he recalled. “I couldn’t wait to get into a game. I just felt like I was going to do the job every time I walked out there. Not that I did, but I just felt like that I was. I had that kind of confidence.”

It was that confidence and performance that finally gave Bradey a shot at the majors—with a push from his manager. “If it hadn’t been for Lou Fitzgerald, I may never have gotten a shot. Lou stayed on Paul Richards (Colt .45s’ general manager) and the scouts constantly. I think they finally heard Lou and Clint Courtney say that I needed to get a look.” Bradey was called up to the major leagues on Friday, September 25, with eight games left in the season. “I was told I’d be used as a reliever,” he said. “Lum Harris was the manager—he took over from Harry Craft who had been fired about a week before.”

On his first day wearing a major-league uniform and with his family in the stands, Bradey experienced his first action, as a reliever in the eighth inning against the Los Angeles Dodgers. On this night 5,323 came out to witness the final night game in Colt Stadium history. When Bradey came on to pitch in the eighth inning, the Colts had only two hits and were down 6-2. But put in perspective, it was a night he would never forget. Future Astros greats Joe Morgan, Bob Aspromonte, Jim Wynn, Rusty Staub, and Jerry Grote were all on the field backing up the “rookie” pitcher. Future Hall of Fame umpires Doug Harvey (home plate) and Jocko Conlan (third base) were on the field.

The first batter Bradey faced, Johnny Roseboro, flied out to Wynn in center field. Second baseman Nate Oliver singled and stole second. Grote’s throw ended up in center field and Oliver advanced to third base, then scored an unearned run on a groundball. Bradey then struck out Dodgers pitcher Ron Perranoski. Bradey was taken out for a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the inning. He recalled, “I was about as nervous as anyone could be. With the team losing the game, it’s always kind of tough to take, but as a reliever, you always look to the next game.”

The next day, a Saturday, was an off day in deference to college football, which is king in Texas. Sunday, September 27, was the final game in Colt Stadium, as the Astrodome was to be the team’s new home for the 1965 season. The Colts won, 1-0, in 12 innings but Bradey didn’t get into the game.

On Monday the Colt .45s flew to California to close out the season in San Francisco and Los Angeles. Bradey didn’t get into Tuesday’s game, but on the next day, September 30, Don appeared in his second major-league game, and earned a decision, albeit a losing one, thanks to two errors by Houston infielders. He entered the game in the 11th inning with the score 1-1. He got Willie Mays on a pop-up and struck out Jim Ray Hart. Then he walked Tom Haller, and Orlando Cepeda singled. Haller stopped at second. Duke Snider, in the next-to-last at-bat of his career, grounded to rookie second baseman Joe Morgan, who booted the ball, loading the bases. Jim Davenport was up next and he grounded to third baseman Eddie Kasko, who promptly fumbled the ball, allowing Haller to score the winning run. Houston Post sportswriter Mickey Herskowitz noted that Bradey’s teammates “gave the Giants five outs in the 11th.” “I thought Bradey looked good,” manager Harris said.

The Colts lost the finale of their series in San Francisco and moved on to Los Angeles for a three-game season-ending series. Harris surprised Bradey by deciding that he would start the final game of the season, which also happened to be Bradey’s 30th birthday. “When I got to the clubhouse on the day of the game, after I was dressed, the manager comes over and hands me a ball and says, ‘You’re starting.’ All this is about an hour and a half before the game. I had no idea that I was starting. I had come up with the understanding that I would be used strictly as a relief pitcher. So when I went out to warm up, I had more butterflies than I think I ever had in my life. …”

After the Colts went quietly in the top of the first, Bradey faced the first of his eight batters in the bottom of the inning. Maury Wills and Junior Gilliam singled and Willie Davis hit a sacrifice fly. Tommy Davis flied out. At this point, with two out and Gilliam on first, the inning turned ugly. Darrell Griffith doubled and Gilliam moved to third. Johnny Roseboro singled, and both Gilliam and Griffith scored with Roseboro going to second base as Rusty Staub bobbled the ball in right field. Bradey intentionally walked Ron Fairly. As Bart Shirley batted, the Dodgers executed a double steal. Then Bradey threw a wild pitch and Roseboro scored with Fairly moving to third. Bradey then walked Shirley, and Harris came to the mound and removed Bradey. “Lum Harris didn’t say anything when he took me out,” Bradey said. “Some guys on the bench patted me on the back and said hang in there.” The Dodgers won the game, 11-1. Bradey gave up five earned runs in two-thirds of an inning on five hits, two walks, and a wild pitch. “It was probably one of the worst games I ever pitched,” Bradey said. “At that time, it was more embarrassing than anything. Looking back now, it is kind of something—a lot of people don’t get to play in the major leagues.”

Bradey’s 1964 major-league season – and his major-league career – ended with three games, an 0-2 record, 2 1/3 innings pitched, six hits, seven runs, five earned runs, three walks (one intentional), two strikeouts, one wild pitch and a 19.29 ERA.

As spring training of 1965 drew near, Bradey found out he was not in the Astros’ plans for the major-league team and he balked at their contract offer. “When I found out I was assigned to Amarillo (formerly the San Antonio franchise), I just about didn’t go,” he said. “I was ready to retire. I had played against Amarillo and that was one terrible ballpark to pitch in. It was windy. … In one game, I saw the shortstop calling for a ball, then the left fielder calling for it, and next thing you know, it’s a home run. It was a tough park to play in. … I eventually did sign, didn’t go to spring training over a contract issue, wasn’t in shape and in my first game I pitched, I gave up a home run with a curveball. That was not a good way to start the season. And an Amarillo sportswriter came up with ‘Boom Boom’ Bradey. All the guys called me Boom Boom from then on. But the only reason I stayed and went to Amarillo was because Lou Fitzgerald was the manager.” Bradey was a full-time reliever and had a 9-11 record in 50 games.

After the season Bradey went back to Charlotte, worked in the mill, and called up Phil Howser, the general manager of the Charlotte Hornets of the Southern League, who were affiliated with the Minnesota Twins. Bradey wanted to be near home in the twilight of his baseball career. He also thought a new team might be his last chance to make it back to the major leagues. Howser told Bradey that if he could get his release from Houston, Charlotte would sign him. Houston agreed and Bradey became a Hornet for 1966. “It was fun playing at home, family getting to come to the ballpark, people from high school,” he said. “I thought maybe even with the Twins, if I could have that one more ‘good year,’ that maybe I’d get another look, but it didn’t happen.” Used almost exclusively as a reliever, he ended the season with a 4-7 record and a 2.14 ERA.

In 1967 Bradey again was a reliever but started five games. After pitching in 30 games with a 1-4 record and a 2.63 ERA, “That tendinitis came back and there was just no way I could pitch.”

It was time for him to find another career. He went to work for Holman Moody, an auto racing team and engine manufacturer. Bradey started in the warehouse and then moved into parts and sales. In 1973 Holman Moody began helping the Ford Motor Company with an automotive emissions program. Eventually Bradey went to work for Ford in Michigan. Nancy, who was working for the Celanese Corporation in the Charlotte area, was able to transfer to Michigan as well. The family first moved to Southfield, Michigan, and then to West Bloomfield. For the next 24 years, Bradey worked in training, engineering, and recertification programs for Ford. He retired in 1997.

The plan was for Nancy to retire in late 2000, and then they would move south to be near their children. But in April 2000, after 47 years of marriage, Nancy died suddenly. “Nancy was a very special person,” Bradey said. “For all those years she enjoyed being around baseball. I think it was because I was playing, she wanted to be there. We did everything together—all our life together with the kids. I thought about that traipsing around the country and she never complained. She was always there to back me up.”

Afterward Bradey moved to Murfreesboro, Tennessee, where his son lived. In December 2005 he married a neighbor, Betty Charlton.

Did he miss baseball? “I did when I left it. It’s kind of like retirement. It took a couple of years for it to sink in. Every time spring training would come around, it was like well, not going this year. It was an adjustment. Every one asked what do you do after baseball, and I say, you find a job, unless you made the big bucks! But when I signed, not many made the big bucks. I viewed it as you had a good ride; you enjoyed it; didn’t get hurt. I saw so many get hurt and end their careers because of injuries. Except for the tendinitis at the end of my career, I was blessed by not having any serious health problems during my baseball playing days.”

Reflecting back on his short time in the majors, Bradey said: “It’s unbelievable to me how many people I’ve been involved with because of those three games in the majors. … It’s like the minor leagues didn’t mean anything, but those three games in the major leagues, wow, like I was there for ten years. It’s hard to believe. … I met some wonderful people, and I’m still meeting great people from that experience. At times it was really tough especially being away from family and all, but I had a great time. I enjoyed it immensely.”

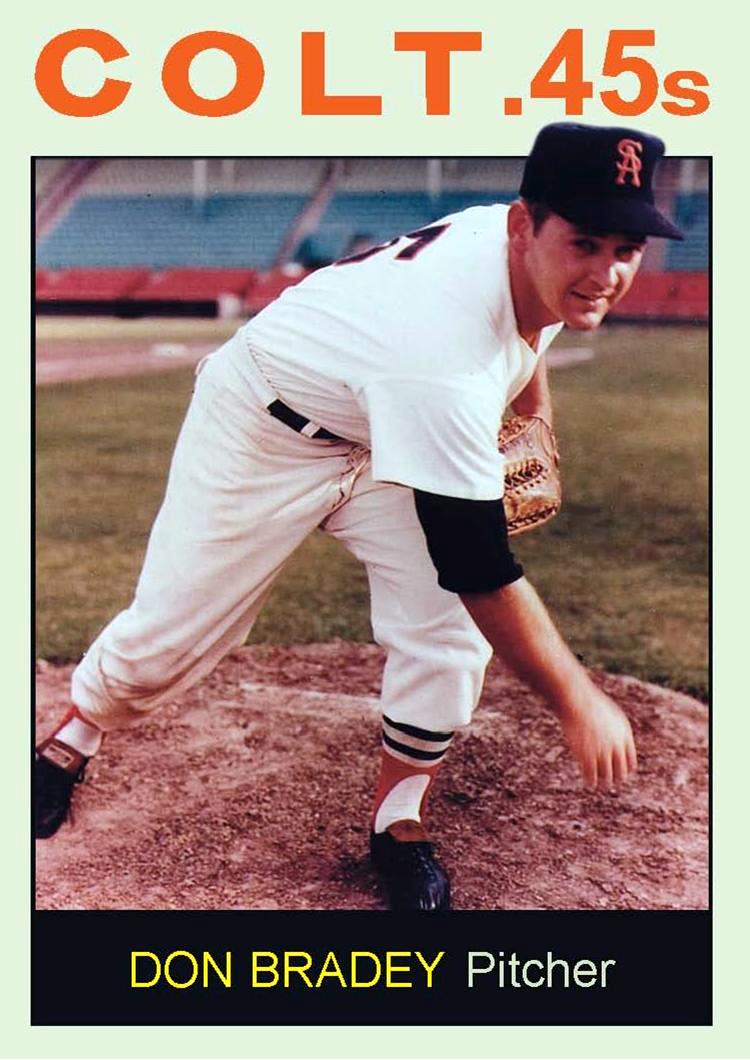

An example of this continued connection with baseball is reflected in Bradey’s baseball card. Three games in the majors does not provide the type of career that necessarily earns one a baseball card, and of the 82 players who played for the Colt 45s, Bradey is the only one who never appeared on a card at one time or another during his career. However, in 2010, Colt .45s card collector Glynn Ligon rectified that. After contacting both the Astros and Bradey, Ligon found out neither had a photo of Bradey in a Colt 45s team uniform. Since he only suited up for two games in a home Colt uniform, and then six games in Houston’s road uniforms, no one seemed to have taken a picture of Bradey in his major-league uniform. So Ligon used a picture supplied by Bradey in his San Antonio Bullets uniform—just before he was called up to the Colt .45s—to produce the one and only Don Bradey card (pictured above).

Sources

Interviews with Don Bradey December 13, 2009, July 25 and September 12, 2011

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph

Colorado Springs Free Press

Houston Chronicle

Houston Post

Los Angeles Times

New Orleans Times Picayune

New York Times

San Francisco Examiner

San Francisco Chronicle

The Sporting News

Telephone interview with Tal Smith, September 13, 2011

Ligon, Glynn. “The Bradey Card,”

http://colt45scards.squarespace.com/the-bradey-card-12162010/

Card photo courtesy of Glynn Ligon and www.colt45scards.com

Charlotte Observer

Cleveland (Tennessee) Banner

Petersburg (Virginia) Progress-Index

Reed, Robert. A Six Gun Salute: An Illustrated History of the Colt .45s. (Houston: Gulf Publishing Company, 1999)

Ray, Edgar W. The Grand Huckster: Houston’s Judge Roy Hofheinz, Genius of the Astrodome. (Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1980)

Corbett, Warren. The Wizard of Waxahachie: Paul Richards and the End of Baseball as We Knew It. (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 2009)

King, David. San Antonio at Bat: Professional Baseball in the Alamo City. (College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 2004)

About Holman Moody—http://www.mshf.com/hof/holman_moody.htm

Full Name

Donald Eugene Bradey

Born

October 4, 1934 at Charlotte, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.