William Hoy

If William Ellsworth Hoy were playing today, he would not be called “Dummy”–not by players nor by fans nor by the media. He’d be “Bill” or “Billy,” perhaps “Will” or “Willie,” maybe even “Ellie.” He wouldn’t be a deaf mute, either. He’d be “aurally and vocally challenged.” But back when Hoy was playing, nicknames were descriptive, often to the point of cruelty. To Hoy, his condition wasn’t an excuse; it was what it was. Indeed, he referred to himself as “Dummy” and politely corrected those who, for whatever reason, called him “William.”

If William Ellsworth Hoy were playing today, he would not be called “Dummy”–not by players nor by fans nor by the media. He’d be “Bill” or “Billy,” perhaps “Will” or “Willie,” maybe even “Ellie.” He wouldn’t be a deaf mute, either. He’d be “aurally and vocally challenged.” But back when Hoy was playing, nicknames were descriptive, often to the point of cruelty. To Hoy, his condition wasn’t an excuse; it was what it was. Indeed, he referred to himself as “Dummy” and politely corrected those who, for whatever reason, called him “William.”

Hoy would have been an exceptional man with or without his handicap. After his baseball career was over, he used his celebrity status to foster the needs and concerns of the deaf. He had a zest for life and once walked 72 blocks at the age of 80 to see his son, Judge Carson Hoy, preside in court. At that advanced age he also danced the Charleston and pruned trees on his farm.

William Ellsworth Hoy was born in Houcktown, Ohio, on May 23, 1862. His parents, Rebecca Hoffman and Jacob Hoy, were of English-German and Scottish stock and had a farm in Houcktown. William had three brothers, Smith, Frank, and John, as well as sister Ora. Contracting meningitis when he was three years old left William deaf and mute. Hoy entered the Ohio School for the Deaf in 1872, graduating in 1879. Highly intelligent and hardworking, he was valedictorian of his high school class. In those days many deaf people were either employed or self-employed as shoemakers or shoe repair people. Hoy was no exception, and in his early twenties opened his own shoe shop. During the summer in his hometown many of the rural people went barefoot. Business would grind almost to a halt then, and Dummy would play ball outside his shop with the local kids. One day a man passed by and saw Dummy playing. He was impressed but moved on when he found out Dummy was deaf. The man returned the next day, however, and asked Hoy if he would be interested in playing on the Kenton, Ohio, team against its bitter rival Urbana. Hoy accepted the invitation. Billy Hart, the Urbana pitcher, was a professional, but Dummy had no trouble solving him for some base hits. The following day Dummy closed his shop and set out for the Northwest League in search of starting a professional baseball career. Some teams turned him down because of his handicap, but he caught on with Oshkosh in Wisconsin in 1886. Hoy was a smart, fast and alert ballplayer who put together arguably “the greatest career of any seriously handicapped player” (Shatzkin and Charlton, 494).

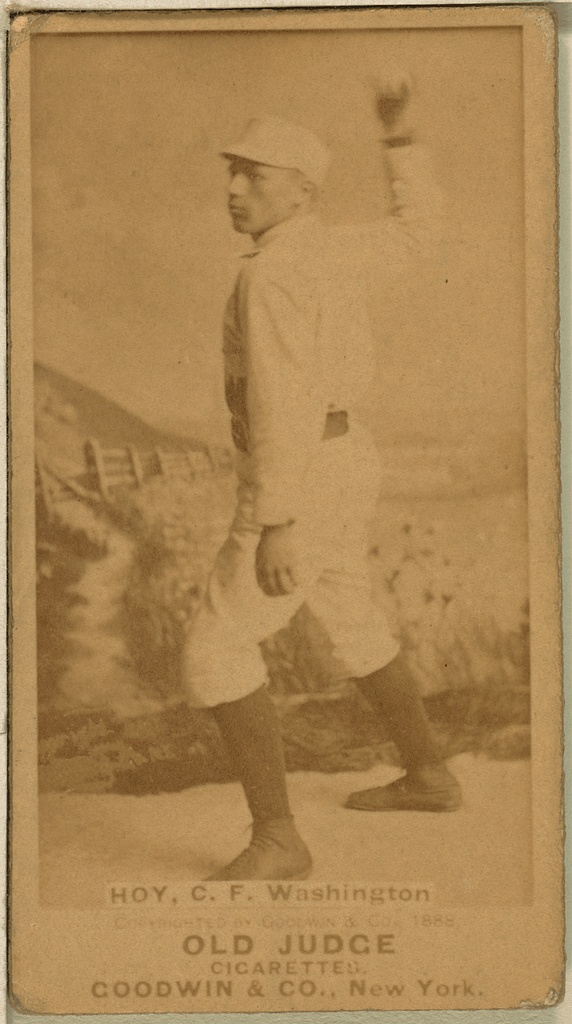

Hoy began his major league career in 1888 with Washington of the National League. A left-handed batter and right-handed thrower, he played with Buffalo, St. Louis, Cincinnati, Chicago and Louisville. When Hoy joined the Washington ballclub, he posted a statement on the clubhouse wall: “Being totally deaf as you know and some of my teammates being unacquainted with my play, I think it is timely to bring about an understanding between myself, the left fielder, the shortstop and the second baseman and the right fielder. The main point is to avoid possible collisions with any of these four who surround me when in the field going for a fly ball. Whenever I take a fly ball I always yell I’ll take it–the same as I have been doing for many seasons, and of course the other fielders let me take it. Whenever you don’t hear me yell, it is understood I am not after the ball, and they govern themselves accordingly.” Hoy’s yell was actually a squeak. Hoy was with Buffalo in the Players League in 1890, with the St. Louis team of the American Association in 1891, then back with Washington in the National League in 1892 and 1893. He moved on to Cincinnati of the National League in 1894, where he stayed until going to Louisville of the National League in 1898 and 1899. He then played for Chicago of the American League in 1900 and 1901. He spent one more season with Cincinnati in 1902 and finally ended his baseball career with Los Angeles of the Pacific Coast League in 1903. Hoy’s moving around made him one of 19 players to play in four major leagues.

All told, Hoy played in 1797 games with an average of .288 that included 2048 hits, 1429 runs, 40 homers and 725 runs batted in. Possessing great speed, he is credited with 596 steals. However, it is difficult to compare him to modern-day players because during his time going from first to third or second to home on a single was considered a steal. This rule was in effect from 1886 to the end of the 1897 season. Nevertheless, Hoy’s ability to take the extra base shows he was an outstanding runner. A small man standing only 5′ 6″ inches tall and never weighing more than 160 pounds, he gave all he had in his small stature. Hoy is one of three outfielders to throw out three base runners at home plate in one game. On June 19, 1889, he threw perfect strikes to catcher Connie Mack to throw out runners attempting to score from second base. In 1900 with the White Sox, Hoy had 45 assists. He has a career mark of 274 assists. (See Note)

Tommy Leach, Hoy’s roommate in 1899, said, “We got to be good friends. He was a real fine ballplayer. When you played with him in the outfield, the thing was that you never called for a ball. You listened for him and if he made this little squeaky sound, that meant he was going to take it.” Leach went on to say, “We hardly ever had to use our fingers to talk, though most of the fellows did learn the sign language, so that when we got confused or something we could straighten it out with our hands.”

Some historians credit Hoy with umpires using hand signals for balls and strikes and safe and out calls, but their view is open to question. Bill Deane challenges that claim. Deane said, “We can find no contemporary articles about Hoy, or even any written while he was alive, that claim a connection between Hoy and the umpire’s hand signals–much less any claim by Hoy himself.” Bill Klem, a showboating umpire who began his umpiring career two years after Hoy retired, is officially credited with inventing hand signals as noted on his Hall of Fame plaque.

Hoy was directly involved in a funny situation when he was with the Washington club. The team was scheduled to play an exhibition game in Paterson, New Jersey, but the traveling secretary forgot to make a special note of it to Hoy. When the team was rounded up for the train trip to Paterson, Dummy was among the missing. A few players went up to his room to see what was the matter. Loud knocking and raised voices, of course, were of no avail. One little guy tried to squeeze inside the transom but couldn’t get through. The players tried to squeeze a bellboy over the transom, but he was too big to hoist over. Then the players threw several plugs of tobacco at Hoy, hitting him in the shoulder but also to no avail. A pack of cards went into effect as they sailed all around Hoy. Still no response. Finally, a set of keys was sent through the transom tied to a bed sheet and dragged across Hoy until it caught in his night shirt whereupon he sleepily awoke to find a bunch of playing cards lying all over him. Thinking his mates were playing a trick on him, he quickly grabbed a pitcher of water and flung it at the heads peeping at him from the transom. Apologies and explanations followed, but from then on Hoy was always informed of any changes that were to occur.

A historic moment came about on May 26, 1902, when Luther Haden “Dummy” Taylor, pitching for the Giants, faced Dummy Hoy of the Cincinnati Reds. When Hoy came to bat for the first time, he greeted Taylor by hand signing, “I’m glad to see you!”–and then cracked a single to center. Forty years later the two met in Toledo during the Ohio State Deaf Softball Tournament held on Labor Day Weekend in 1942. They were batterymates (Taylor pitching and Hoy catching). At the time Taylor was 67 and Hoy 80.

On October 26, 1898, Hoy married Anna Maria Lowry, who was also deaf. Anna Maria became a prominent teacher of the deaf in Ohio. They raised three children, Carson, Carmen and Clover. Two others died during childbirth. A third succumbed to the Spanish flu. Carson became a lawyer and a jurist. Carmen and Clover became schoolteachers.

A caring human being, Hoy took on the responsibility of raising his nephew, whose mother had passed away and whose father was in bad health. Ora Hoy had married Elmer Helms. The marriage produced a son, Paul Hoy Helms, who would become the founder and sponsor of the Helms Athletic Foundation and Helms Hall, in Los Angeles. The family took care of young Paul, and Dummy Hoy lent him money for his education. Paul graduated from Syracuse University in 1912 and settled in California, where he became a millionaire through wise investments; in addition, he founded the Helms Bakery, which financed the Olympic Committee for the United States in 1932 and 1936.

After his retirement from baseball Hoy bought a farm in Mount Healthy, Ohio, where he succeeded as a dairy farmer. He also worked for a time as a personnel director for the Goodyear Tire Company. When all his children had reached adulthood, he sold the farm and made a connection with a book firm and remained there until he was 75. After retiring from business, he continued his involvement in baseball. He received a silver pass from both the American and National League presidents and used it frequently. He never liked to go to opening day games because he felt there was too much of a crowd. He also attended five or six meetings a year of the old timers club. In 1951 Hoy became the first deaf athlete elected into the American Athletic Association of the Deaf Hall of Fame. A baseball field at Gallaudet University in Washington, DC, was named for him.

Anna Maria died after several months of illness on September 24, 1951, at age 75.

There has been a push by many people to have Dummy Hoy elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, but all attempts have failed. The 19th century figure picked for the Hall in 1999 was Frank Selee, the manager of the Oshkosh team where Hoy got his start in baseball. In 2000 Bid McPhee was the 19th century player chosen despite the push for Hoy. Hoy supporters asked, “What’s McPhee have that Hoy doesn’t?” Since 1991, the USA Deaf Sports Federation has been lobbying to get Hoy into the Hall of Fame. Joan Sampson, Hoy’s granddaughter living in Cincinnati, said, “I’m sure my grandfather would love to be in Cooperstown. He was very proud of his career.” But she felt his chances of entering the Hall were very slim. However, in 1941 Hoy was inducted into the Louisville Colonels Hall of Fame. Hoy has also been honored by the Ohio School for the Deaf, Hancock County Sports, Ohio Baseball, “Stars in Their Time,” the Cincinnati Reds, and the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals.

In 1961 Hoy, now 99, threw out the ceremonial first pitch before game three of the World Series between the Reds and the Yankees in Cincinnati. He died on December 15, 1961. Hoy by living to the age of 99 was a bridge between the old game and the modern one. He was living proof of how the game had changed over the years. Hoy set the record at the time for the oldest living ex-major leaguer. Surviving him were son Carson, daughter Clover Skaggs of Sacramento, seven grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren. Two of the grandchildren are Judson Hoy, a Cincinnati lawyer, and Bruce Hoy, a Hollywood and New York entertainer.

Hoy never sought the limelight and did not look for praise. However, in December of 1987, a play called The Signal Season of Dummy Hoy was produced telling of the 1886 season when hand signals were supposedly developed to aid Hoy. The play received mixed reviews.

William Ellsworth Hoy overcame his handicap not only in a successful baseball career but also as an ordinary citizen. He was admired both as a hero and as a solid citizen. Hoy was truly a man for all seasons.

Note

Total Baseball, Baseball-Reference.com, and The Ballplayers differ slightly on Hoy’s career totals. Total Baseball claims 2,048 hits, Baseball-Reference says 2,044, and The Ballplayers says 2,054. These sources also differ on runs, RBI, batting average, and steals. While The Ballplayers claims Hoy stood 5’4″ and weighed 148 pounds, Total Baseball lists Hoy at 5’6″ and 160 pounds.

Sources

Appendices B “Decisions of the Special Baseball Records Committee” and C “Major Changes in Playing Rules and Scoring Rules.” The Baseball Encyclopedia. 10th ed. New York: Macmillan, 1996.

Chase, Dennis T. “Tom.” “Hoy, William Ellsworth ‘Dummy.’” Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball. David L. Porter, ed. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000.

Dummy Hoy files at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum at Cooperstown, New York.

The Dummy Hoy Homeplate, Online Website.

New York Times, Obituary, December 15, 1961.

Ritter, Lawrence S. The Glory of Their Times: The Story of the Early Days of Baseball Told by the Men Who Played It. New York: Macmillan, 1966.

Shatzkin, Mike, and Jim Charlton. The Ballplayers. New York: William Morrow, 1990.

Full Name

William Ellsworth Hoy

Born

May 23, 1862 at Houcktown, OH (USA)

Died

December 15, 1961 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.