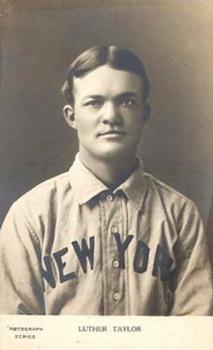

Luther Taylor

It was raining on October 11, a day that Luther Taylor had awaited since he began playing in the major leagues, a chance to start a World Series game. So the game was cancelled. The next day Christy Mathewson would take the mound, to pitch the second of his three shutouts in the 1905 Series. It was the only World Series to end with shutouts in each of five contests, with the Giants winning 4 to 1.

It was raining on October 11, a day that Luther Taylor had awaited since he began playing in the major leagues, a chance to start a World Series game. So the game was cancelled. The next day Christy Mathewson would take the mound, to pitch the second of his three shutouts in the 1905 Series. It was the only World Series to end with shutouts in each of five contests, with the Giants winning 4 to 1.

During an interview that appeared in The Sporting News on December 24, 1942, Taylor explained simply why he did not start that game on the next day: “Two answers to that one. Matty and Joe McGinnity.”1

Why did a start mean so much to Taylor? It was very simple: If he had gotten the ball the next day, he would have been the first deaf player to play in a World Series.

Luther Haden “Dummy” Taylor was a remarkable character in a time when baseball was beginning to take hold as the national pastime. Taylor was born February 21, 1875, in Oskaloosa, Kansas, to hearing parents Arnold B. Taylor and Emeline Chapman. Luther went to school at the Kansas School for the Deaf in nearby Olathe and graduated in 1895 as valedictorian.2

Luther liked boxing and wanted to be a boxer. He attributed his long life to constant working out in the gym and boxing all comers, but his parents said no and he opted for baseball. Taylor said, “I had visions of being another Bob Fitzsimmons or Jack Dempsey… But Ma and Pa objected.”3

Taylor began his journey to the big leagues after graduation. He pitched for semi-professional teams in Missouri, Kansas, and Illinois. In 1900 he made a minor league team in Albany, New York; his first major league manager, future Hall of Famer George Davis, scouted him. While at Albany, he won 11 and lost 8 and received a call up to the Giants on August 28, 1900. He completed the season with a 4-3 record.

In 1901, his first full big league season, Taylor’s record was 18 and 27 with an ERA of 3.18. He was the workhorse of the staff, collecting a third of the Giants’ 52 wins. Taylor began the 1902 season with Cleveland in the one-year-old American League, where he expected to receive more money to play with them. He had jumped to the new league on the advice of Jim McAleer, a player and manager.

But Taylor was not happy in Cleveland. The players were uncommunicative, having not learned sign language, and the outgoing Taylor was miserable. Early in May Giant owner Andrew C. Freedman sent a friend of his, catcher Frank Bowerman, to try to get him back to the Giants. As Taylor tells it, “Frank sat in the grandstand and every time I walked to the pitching mound and back to the bench he kept talking to me with his fingers. I kept shaking my head ‘No’ and Frank kept boosting the money. Soon, I nodded my head ‘Yes’ and that night I was on my way back to New York with Frank.”4

Before Taylor left Cleveland, Napoleon Lajoie said he was the only deaf mute who was ever tossed out of a ball game for talking back to an umpire. According to Lajoie, “Taylor was having a lot of trouble that day. His lips moved continuously as he pitched, but the umpire ignored him. Finally, Taylor walked to the plate, stuck out his chin and framed some words slowly and distinctly.” The umpire tossed him.5

Dummy Taylor had just one win against three losses, despite a 1.59 ERA, in Cleveland when he jumped the team. Upon returning to New York, he found a club in turmoil. At the top, Freedman was negotiating with John T. Brush over ownership of the team. At the same time John McGraw, who was managing the Baltimore Orioles in the American League, was actively plotting to go to the National League with the Giants. The players would be caught in the middle of this.

Taylor finished the 1902 season with a 7-15 record and 2.29 ERA on a team that John McGraw was developing into a pennant winner. On May 16 of that year the Giants paid a visit to Cincinnati at their new ballpark, the Palace of the Fans. In that game for the first time two deaf-mute players, Taylor and William Ellsworth “Dummy” Hoy, met on a ball field. Hoy, in his last year in the major leagues, had two hits in the game. Taylor had given up no earned runs, but in the eighth the Reds scored three times. Taylor was replaced by a pinch-hitter in the top of the ninth, and the Giants scored five times. Tully Sparks shut down the Reds in the bottom of the inning, giving Taylor the win.

Late in the season John T. Brush became the owner, and things turned around for the Giants. With Brush in the front office and McGraw in the dugout, the Giants became a winner with a 1903 record of 84-55. They finished second, and Taylor had a 13-13 finish, albeit with a 4.23 ERA.

Only three people stayed with the team in 1903: Taylor, Mathewson and Bowerman. The rest of team came from the old Baltimore team and free agents. There was ample reason to keep Mathewson, a future Hall of Famer, and Bowerman, a solid catcher. But why did McGraw keep Taylor?

In large part, Taylor was an above-average pitcher, as his ERAs usually showed, and perhaps because of the challenges he faced, popular with teammates and fans. His teammates learned sign language, he was visible because he was with the Giants, and as the Saturday Evening Post said, “Wherever Taylor goes he will always be visited by scores of the silent fraternity among whom he is regarded as a prodigy.”6

On the mound Taylor had an unorthodox corkscrew delivery. He had a good fastball, curve and a devastating drop ball. But he had another edge. He was adept at stealing other team’s signs because of his eyesight, and he could read a base runner’s intentions by studying his facial expressions.7

His first game with the Giants proved his point. “It was against Frank Selee’s Boston club, one of the best. It had Billy Hamilton, Bobby Lowe, Herman Long, Fred Tenney, Dick Cooley, Jim Slagle, all fast men. Those fellows thought they would take advantage of me because of my deafness. Five of them tried to steal third base and I nailed each one. I walked over to Long, the last man caught, and let him know by signs I could hear him stealing.”8

Taylor was part of the Giants, and they were part of him. Player-manager George Davis learned signs and encouraged his players to do the same. When John McGraw came on he did the same, because Taylor had “a genial, humorous spirit that covets companionship.”9

Fred Snodgrass in The Glory of Their Times said Dummy Taylor would take offense if one did not do sign language. Snodgrass said, “We could all read and speak the deaf and dumb sign language…” He added, “He wanted to be one of us, to be a full-fledged member of the team. If we went to a vaudeville show, he wanted to know what the joke was, and somebody had to tell him. So we all learned.”10

The Giants learned signs and used them in games, at least until opponents caught on. Signs had been used in other contexts with other teams, but the Giants used sign language, especially when Taylor was coaching first base.

Taylor would put on a show when he coached first base. Not only did he give signs to his teammates, but he also showed approval and disapproval of the umpire’s calls. As Taylor put it, “I had a lot of fun with all of them. But they sure gave me all I had coming. Emslie was one of the most kind-hearted. O’Day was fine, too. And Hurst. Rigler was one of the best arbiters who ever called balls and strikes.”11

Some of the encounters between Taylor and umpires border upon the apocryphal, but in his words they are amusing, and showed a different treatment of players and umpires back in the early 1900s.

Hank O’Day may have gotten the last word, or sign, on Taylor. Taylor was coaching first base and O’Day was behind the plate. Taylor was making a spinning motion, indicating that O’Day had wheels in his head. Taylor was telling him off in sign language. O’Day got even, spelling “You go to the clubhouse. Pay $25.”12 O’Day knew sign language, having been raised by a deaf parent and other relatives.

Another umpire, Charlie Zimmer, became irate when Taylor made loud shrieking sound. Teammate Mike Donlin likened it to the “crazed shrieking of a jackass.”13 He used it to rattle opposing pitchers or just to irk the umpires. He chased Taylor for making the sound, perhaps the only time a deaf mute was tossed from a game for making too much noise.

Another time James Johnstone kept the Giants playing in a hard rain against the Cubs. Taylor decided to try to get the game cancelled. He went to the clubhouse and put on a pair of rubber boots. When Taylor came out to coach third base, Johnstone chased him and declared the game a forfeit.14

Hall of Fame umpire Bill Klem also crept into Taylor’s sights. It all began when roommate and friend Mike Donlin taught Taylor the word “catfish.” Klem had piscine features and was so sensitive that anyone who wanted to be thrown out of a game simply had to call him “catfish.” Early in the game Klem had thrown out all of the Giants except Donlin and Taylor. “I said ‘Catfish’ as plainly as I could. Bill looked around. He only saw Mike and me and he chased Mike. As Bill started back to the plate, I repeated it. Bill looked around. He saw me, all alone. He scratched his head. No, he was sure it couldn’t be me.”15

Ironically, Taylor became an umpire when his playing days were over, working in Kansas, Iowa, Nebraska and Illinois from 1915 to 1938 for the House of David and Union Giants. It had to be a “treat” for those who loved to ride umpires, because Taylor couldn’t hear any abuse.

Taylor played five more years for the Giants. In 1904 he went 21-15 with a 2.34 ERA for a team that won the National League pennant. They didn’t play the World Series that year because John McGraw and John T. Brush did not want to play a series with what they called a “minor league club.”

They played the Series in 1905. Taylor contributed a 16-9 mark and 2.66 ERA to the Giants’ efforts, but was kept from starting the third game of the series because of rain. From 1906 through 1908 Taylor was effective, winning 36 and losing 21. Unfortunately, his arm went bad and ended his career in 1908. He finished up with 116 wins, 106 losses, and a solid 2.75 ERA. Taylor played another five years for Buffalo, Montreal and New Orleans, but it was clear that he was through as a pitcher.

Taylor went back to the Kansas School for the Deaf and coached five different sports, including football, boys’ and girls’ basketball and baseball until 1923 when he went to the Iowa School for the Deaf in Council Bluffs. His teams ran up outstanding records in both football and baseball.

Taylor began working for the Illinois School for the Deaf in Jacksonville in 1933. He was a coach, teacher and housefather for the school until 1949. One of his proudest moments came in 1945 when Dick Sipek played with the Cincinnati Reds. Sipek, a deaf mute, was the first player to escape the “Dummy” nickname.

Taylor told Baseball Magazine that the nickname “Dummy” was not a problem. “In the old days Hoy and I were called Dummy. It didn’t hurt us. Made us fight harder. Nobody ever felt sorry for me …”16

In his life after baseball Taylor was a popular figure, bridging the gap between those who hear and those who don’t. He often told stories about his days with the Giants.

“Frank Bowerman was the Giants’ best catcher. He made Matty one of the greatest pitchers before Bresnahan came to New York.” He added, “He had a style of his own and steadiness was such that a pitcher contracted it like a disease. A pitcher’s control was always better when Bowerman caught him. He was tops …”17

As for Mathewson, Taylor said he was a square shooter and “King of them all. He had everything and could put the ball wherever he wanted to. Besides his arm, he had the best head on his shoulders any pitcher in the game ever had, and the heart of a lion.”18 According to the National League Service Bureau, Taylor was renowned as a good fielder, and Mathewson learned from him.19

He enjoyed playing for John McGraw. Taylor said he was above everyone, even Frank Chance of the Cubs and Fred Clarke. “All of them were fine managers, but I believe McGraw was one of the wisest managers I ever pitched for, and he knew how and when to pick his men.” Taylor continued, “McGraw treated players liberally with salaries and demanded good hotels for his men.”20

Taylor was a live wire in training camp. Sam Crane, a sportswriter, noted that Taylor was full of life. “Bresnahan began to spar with him, but Luther is pretty good with his hands and knocked off Bresnahan’s dicer the first crack out of the box. … Needham tried to break in with it, but Luther looked at Tom’s knotted digits and spelled out on his fingers: ‘Another Bowerman; I’ll bet he has a brogue.’”

When Bresnahan or Bowerman went to the mound, they would always use sign language to get their point across. Taylor was in a way “… baseball’s silent jester, the forerunner of today’s team mascots. He would use his mime skills to mock the umpires behind their backs to the delight of New York crowds.”21

Mike Donlin was Taylor’s roommate on the road. Donlin liked show business and married a vaudeville star. But Taylor and Donlin got along: “Funny, Mike was great when he drank. I would sneak into a bar and grab him many a time so as not to let McGraw know. But then, that was the Irish for you in my days. Besides, McGraw and Mike, McGann, Billy Gilbert, Bresnahan, George Browne all were Irishers, and proud of it.”22

Taylor would often leave the hotel door open in the evening because of his inability to hear a knock. When players knew he was entertaining deaf friends, they would break up the conversation by turning off the lights. Nevertheless, Taylor gave as good as he got.

Taylor was married three times, but had no children. His first wife, Della Ramsey, died in November 1931. His second wife, Lenora Borjquest, came from Iowa; they were married only a short time before she died. His third wife, Lina Belle Davies, came from Little Rock, Arkansas, and they met at the Illinois School for the Deaf. They were married on August 29, 1941.

William Milliken, Athletic Director with the Jacksonville School for the Deaf said, “He’s a wonder and a big favorite with all in charge of the school, the faculty, the children and their parents. … Well, as soon as spring arrived, we laid out a diamond, issued a call for candidates and our school team was one of the strongest in Central Illinois.”23

Taylor often met with former teammates and on August 7, 1941, came back to New York and visited Yankee Stadium. He was with Andy Coakley, Columbia’s baseball coach, who had discovered Lou Gehrig. But this day their conversation went back to their playing days. Coakley lost to Christy Mathewson in the 1905 World Series by a score of 9-0 in game three. They communicated by pen and paper.24

Taylor died on August 22, 1958, at the age of 82, just 11 days after suffering a presumably mild heart attack. He was clear-minded and in excellent spirits to the end. He is buried in Baldwin City, Kansas, with his first wife Della.

Taylor accomplished a great deal in his life, building a bridge between those who could hear and those that didn’t. In 1936 he was awarded a lifetime pass to the major leagues. In 1952 he became the second player inducted into the American Athletic Association for the Deaf. After he died, the Kansas School for the Deaf named its gymnasium for him in 1961. In 2006 Luther Taylor was inducted into the Kansas Baseball Hall of Fame.

A monument was erected on Taylor’s gravesite on May 24, 2008.

This biography is an expansion of one written by Sean Lahman which appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Notes

1 The Sporting News, December 24, 1942.

2 Kimberley Dawson, Deaf Sports Review, Winter 1993, and Dummy Taylor Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

3 The Sporting News, December 24, 1942.

4 The Sporting News, December 24, 1942.

5 Dummy Taylor Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

6 Sean Lahman, “Dummy Taylor,” in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

7 Lahman.

8 The Sporting News, December 24, 1942.

9 Lahman.

10 Lawrence S. Ritter, “Fred Snodgrass,” The Glory of Their Times (New York: Quill, 1984).

11 The Sporting News, December 24, 1942.

12 Saturday Evening Post, October 2, 1943.

13 Lahman.

14 The Sporting News, December 24, 1942.

15 The Sporting News, December 24, 1942.

16 Baseball Magazine, September 1945.

17 Baseball Magazine, September 1945.

18 The Sporting News, December 24, 1942.

19 Dummy Taylor Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

20 The Sporting News, December 24, 1942.

21 Timothy Wayne, “Dummy vs. Dummy: A Brilliant Confrontation,” Deaf American, undated article found in Dummy Taylor Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

22 The Sporting News, December 24, 1942.

23 Dummy Taylor Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

24 Dummy Taylor Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Full Name

Luther Haden Taylor

Born

February 21, 1875 at Oskaloosa, KS (USA)

Died

August 22, 1958 at Jacksonville, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.