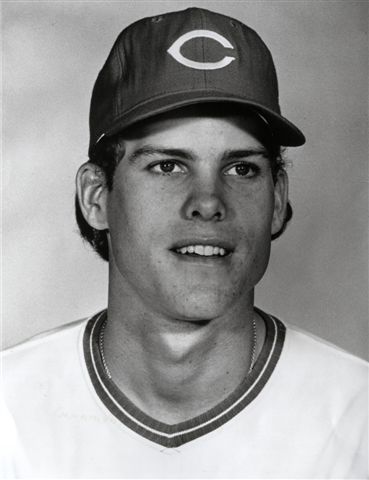

Rawly Eastwick

In art, a painter may create masterpieces on canvas. In baseball the verb “paint” applies to a craft no less skillful. The Dickson Baseball Dictionary defines the verb as “… To throw pitches over the edges of the plate, which appear to be dark or black because of the contrast of the white rubber plate with the surrounding dirt.”1 The ability to keep the ball away from the middle of the plate and on the edges is crucial to the success of any pitcher. It is truly unusual to find a pitcher to whom the act of putting paint on canvas holds as much meaning as putting a fastball on the outside corner. Rawly Eastwick was an exception, as professionally he painted corners, and on the side he painted landscapes.

In art, a painter may create masterpieces on canvas. In baseball the verb “paint” applies to a craft no less skillful. The Dickson Baseball Dictionary defines the verb as “… To throw pitches over the edges of the plate, which appear to be dark or black because of the contrast of the white rubber plate with the surrounding dirt.”1 The ability to keep the ball away from the middle of the plate and on the edges is crucial to the success of any pitcher. It is truly unusual to find a pitcher to whom the act of putting paint on canvas holds as much meaning as putting a fastball on the outside corner. Rawly Eastwick was an exception, as professionally he painted corners, and on the side he painted landscapes.

Rawlins Jackson Eastwick, III was born on October 24, 1950, in Camden, New Jersey, and grew up in the upper-middle-class Philadelphia suburb of Haddonfield, New Jersey. He was the youngest child of Rawlins Jackson Eastwick, Jr. and Ruth Brown Eastwick. The elder Eastwick worked as an engineer for Bell Telephone, and friends simply called him Bud.2 While Rawly was given his father’s name, he was actually the youngest in his family, arriving after a set of twin brothers, Robert and Richard, a sister, Nancy, and his own twin brother, Ralph. Of his name, the youngest Eastwick said, “(My parents) knew what they wanted to name one of us, but they ran out of names. So they were standing around wondering what to name me, and my father said, ‘Give him my name.’ I’m glad they didn’t name me Walter or Horatio or something like that.”3 At Haddonfield High School, Eastwick earned all-state honors on the diamond and was an honorable mention All-American in 1969. He also excelled as a wrestler, twice winning the district high-school championship.4

Selected by the Reds in the third round of the 1969 amateur draft, the 18-year-old Eastwick struggled in his first professional season, posting an earned-run average near 5.00 for the Gulf Coast League Reds and allowing almost two baserunners an inning. His performance ebbed and flowed over the few seasons before he really asserted himself in Double-A in 1972, when he posted a 2.34 ERA in 119 innings (all in relief) and an Eastern League-leading 20 saves for Trois-Rivieres (Quebec). After two seasons at Triple-A Indianapolis, Eastwick was called up to the Reds in September 1974 and made his debut against the Braves on the 12th in Cincinnati against the Atlanta Braves. The first batter he faced was Hank Aaron, who earlier in the season had broken Babe Ruth’s career home-run record. Aaron flied out to center this time. (Eastwick became the answer to a trivia question in the last game of the season when he surrendered Aaron’s 733rd and final National League home run.) In his brief cameo at the end of 1974, Eastwick pitched eight times and earned two saves.

Eastwick pitched well in spring training of 1975 but was sent to Indianapolis when the final cuts were made. Reds pitching coach Larry Shepard encouraged him, saying, “I don’t think it’ll be long till you’re back.”5 Taking Shepard’s words and a positive attitude with him, Eastwick was not gone long; he was recalled by the Reds in mid-May. When he arrived in the clubhouse none of his teammates had been expecting him, and he was asked what he was doing there. The rookie matter-of-factly stated, “They told me to come here, so I came.”6 He also brashly asserted, “I’ve got a job to do. I’m here to help this team win.”7

When Eastwick was called up, infielder John Vukovich was sent to Indianapolis to clear a roster spot for him. Pete Rose was moved from left field to third base and George Foster was installed in the lineup as the everyday left fielder. After these moves the Reds ripped off a 63-19 run between late May and mid-August that propelled the team from five games back in the NL West to 17½ games ahead of the Dodgers, putting the division race away.

Eastwick started out slowly with the Reds; he had a lusty 5.93 ERA on July 1. Veteran starter Don Gullett was on the disabled list at the time, and Shepard challenged Eastwick: “Just who do you suppose is going to be the one to go when Gullett gets healthy? You, that’s who. Unless you start throwing the ball. You’re trying to guide it, to be too fine. The way you throw, just go ahead and turn it loose.”8

On July 24, at Shea Stadium, Eastwick got his chance to turn it loose. Entering a 2-1 game against the Mets with runners on first and second and two outs in the ninth inning, he blew away slugger Dave Kingman with three fastballs to end the game. “I stair-stepped him,” Eastwick said afterward. “A low fastball, a higher fastball, and a high fastball.”9

As the 1975 season developed so too did Eastwick’s importance to the Reds. The fresh-faced 24-year-old and another rookie reliever, 23-year-old left-hander Will McEnaney, formed the “Kiddie Korps,” anchoring the back end of the bullpen for manager Sparky Anderson, known as baseball’s “Captain Hook” because of his reliance on his relief pitchers. Eastwick finished the season with a record of 5-3, 22 saves and a 2.60 ERA in 58 games, including 40 games finished. His 22 saves tied him with St. Louis’s Al Hrabosky for the National League lead, and he finished second to Hrabosky for the National League Fireman of the Year award.

The 6-foot-3, 185-pound right-hander overflowed with a confidence that could rightly be labeled as arrogance. He claimed to never have a negative thought, and believed that this attitude radiated to the hitter.10 He maintained that he had never been nervous or frightened by anything in his life. Reds second baseman Joe Morgan once ran to the mound during a tense moment in a game and told Rawly, “If you get uptight, step off and take a few breaths.” The unmoved Eastwick later said, “Well, I don’t really know what he was talking about.”11

The rookie believed that his regimen for caring for his arm was best. The regimen? Nothing, and no one was allowed to touch his arm.12 As an 18-year-old in the rookie league, he had challenged a teammate from Chicago with reputed Mafia connections to a fight in the woods. Only Eastwick walked out. His cockiness not surprisingly carried over to the pitcher’s mound. Anderson described him as possessing a “here-it-is-and-now-try-to-hit-it” fastball.13 Regarding his recall from Indianapolis, Eastwick said, “The bullpen needed a shot in the arm. I think I did it.” Bob Hertzel, author of The Big Red Machine, where the quote appeared, wrote that Eastwick made his comment without the least bit of modesty.14

While Eastwick’s self-assurance squared easily with his on-field persona as a fireballing relief ace, it didn’t mesh with his off-field interests. Unlike many ballplayers, he enjoyed reading and talking about current events. He was a painter and a sculptor. He collected art and antiques. A painter since he was a boy, as a big-leaguer he continued to work with pastels and water colors, calling himself an expressionist and painting landscapes and still lifes. He gave one of his works to Johnny Bench as a wedding present, Bench pledging to display it in his living room.15

In the playoff matchup with the Pirates, Eastwick threw three scoreless innings of relief in the Reds’ 6-1 win in Game Two, then relieved McEnaney with a runner on first and one out in the ninth inning of Game Three in Pittsburgh, with the Reds leading 3-2 and only two outs from the pennant. Eastwick gave up a single and two walks, with his second free pass forcing in the tying run. But Cincinnati scored twice in the top of the tenth and the Reds won their third NL pennant in the last six seasons.

For most of the 1975 World Series Eastwick was in line to be the Series MVP. He had pitched in Games Two through Five, allowed one run in seven innings and picked up two wins and a save as the Reds led the Boston Red Sox three games to two. He was the first rookie to earn a win and a save in the same postseason series.16 In Game Six, with the Reds leading 6-3 going in the bottom of the eighth inning, sportswriters in the press box voted Eastwick the MVP.17 Then the first two Red Sox reached base and Eastwick was summoned from the bullpen to relieve Pedro Borbon. He looked untouchable in striking out Dwight Evans and retiring Rick Burleson on a liner to shallow left. With two outs Boston sent up left-hand hitting Bernie Carbo to pinch-hit. Anderson stuck with Eastwick, and it appeared he made the right decision as Eastwick worked the count to 2 and 2. But then he threw a fastball that Carbo launched into the center-field bleachers, tying the score. The Reds’ lead and Eastwick’s World Series MVP award evaporated with one pitch.18 Four innings later Carlton Fisk hit his game-winning home run, and the Red Sox had forced a seventh game. Eastwick didn’t pitch in that game as the Reds rallied and won, 4-3, to capture their first title since 1940. In the champagne-soaked clubhouse after the game, Eastwick declared, “I can’t believe it. What a year. What a rookie year.”19 Eastwick tied for third in the National League Rookie of the Year voting.

Not content to rest on the success of his rookie season, Eastwick was very direct in his plan for 1976. “I want to win the NL Fireman of the Year Award,” he told The Sporting News.20 Toward that end he worked hard in the offseason, running and throwing in the Cincinnati area with McEnaney.

While McEnaney struggled with a severe sophomore slump, Eastwick thrived on his expanded role in his first full major-league season. Pitching in 71 games, he compiled an 11-5 record and a 2.09 ERA in 107⅔ innings. He had a league-leading 26 saves. He finished fifth in the league’s Cy Young voting, but did capture the Fireman of the Year award. The Reds steamrolled through the season, then swept the Phillies in the NLCS and the Yankees in the World Series. Eastwick became the first pitcher to lead the league in saves in his first two major-league seasons since Gordon Maltzberger of the White Sox in 1943-44 (before saves were a statistic).21

Before the 1977 season Eastwick made headlines for his unhappiness with the Reds organization. After the team traded Tony Perez and McEnaney to the Montreal Expos, Eastwick referred to the deal as “stupidity.”22 He also complained that his $29,000 salary in 1976 left him underpaid.

Unable to come to terms on a contract for 1977, Eastwick determined to play out his option year and become a free agent. He suggested that the Reds management had decided to use him less than needed because of his contract situation. In early June the Reds informed him that they were looking to move him by the June 15 trade deadline, and he was almost included in the deal that brought Tom Seaver to the Reds; the Mets were scared off by his contract situation.23 The same day the Reds got Seaver, Eastwick was sent to the St. Louis Cardinals for minor-league pitcher Doug Capilla. His stay in St. Louis was short and uneventful (3-7, 4.70 ERA, four saves in 41 games aside from his continued insistence on becoming a free agent at the end of the season and for his return to Cincinnati in an enemy uniform, during which he was booed loudly.24

After the season Eastwick hit the free-agent market, one of the prized clients of 1970s super-agent Jerry Kapstein. During the winter meetings in Hawaii, they struck a deal with the Yankees for $1.1 million over five years.

The deal was curious from both sides. From Eastwick’s perspective, he was a relief pitcher who voluntarily signed with a club that had reliever Sparky Lyle, the 1977 American League Cy Young Award winner, and had just signed another premier reliever, Goose Gossage (another Kapstein client). Yankees owner George Steinbrenner had been warned before the signing that Eastwick was not throwing well, and there was concern that his arm was dead. Ever the involved owner, Steinbrenner met with Eastwick and Kapstein and decided to sign him anyway.25

Eastwick’s signing with the Yankees proved to be one of the earliest busts in the era of free agency. He made only eight appearances for the Yankees, mostly in garbage time. On June 14, barely six months after signing with the Yankees, he was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies for outfielders Bobby Brown and Jay Johnstone. Eastwick’s status as one of Steinbrenner’s favorites likely kept manager Billy Martin from ever embracing him.26

Eastwick expressed excitement about his arrival in Philadelphia, just across the Delaware River from his hometown of Haddonfield. He talked of living and dying with the Phillies as a boy and expressed regret that he had not signed with them before the 1978 season.27 Despite the good feelings, little changed in Eastwick’s career arc in Philadelphia. He pitched in 73 games for the team in 1978 and 1979, recording six saves and a 4.61 ERA. He was never counted on too heavily in a bullpen that featured veterans Tug McGraw and Ron Reed. The highlight of his Phillies career came on a blustery day at Wrigley Field in May 1979 when he threw two perfect innings to secure a 23-22 win over the Cubs. Before that day he had given up nine runs in his previous 5⅓ innings. But in the ninth inning he retired the side in order to send the game to extra innings at 22-22, then did it again in bottom of the tenth after Mike Schmidt hit a home run in the top of the inning. Eleven pitchers were used by the two teams that day with Eastwick being the only hurler of the game not give up a hit. Eastwick’s Phillies career ended in spring training of 1980, when no-nonsense manager Dallas Green cut him, along with Bud Harrelson, Doug Bird, and Mike Anderson, players the manager felt carried attitude and acted as though they were entitled to a spot on a major-league roster.28

Eastwick signed as a free agent with Kansas City in June, 1980, and spent a month at Omaha of the American Association before being recalled to the Royals. He pitched in 14 games before he was released in late August. The Cubs invited him to spring training on a minor-league deal in 1981. He made the club and threw well as a middle reliever, posting a 2.28 ERA in 30 games. He was released at the end of spring training in 1982, and his professional baseball career was over. Made a millionaire by the Yankees at the age of 27, Eastwick threw his last professional pitch a full year before the Yankee contract was even set to expire. He had been released three times in the interim.

What happened to Rawly Eastwick? Was he blown out by overuse early in his career with the Reds? While Eastwick asserted that he pitched better with more work, the evidence shows that he never even got close to the level of success he attained during his first two seasons in the majors, when he pitched 232⅓ innings, including playoffs and a stint in the minors. While Sparky Anderson acknowledged that it would be unwise to run Eastwick out to the mound every night, he appeared to do just that in 1975 and 1976.

After his playing career ended, Eastwick embarked on a career in commercial real estate in New England. In 2011 he resided with his wife, Sandra, in West Newbury, Massachusetts.

Last revised: May 1, 2014

This biography is included in the book “The Great Eight: The 1975 Cincinnati Reds” (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Mark Armour. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Notes

1 Paul Dickson, The Dickson Baseball Dictionary (New York: Facts on File, 1989), 291.

2 New York Times, October 19, 1975.

3 New York Times, October 19, 1975.

4 1980 Philadelphia Phillies Media Guide.

5 Portsmouth (Ohio) Times, October 18, 1975.

6 Portsmouth Times, October 18, 1975.

7 Joe Posnanski, The Machine (New York: William Morrow, 2009), 115.

8 Anchorage (Alaska) Daily News, July 25, 1975.

9 Bob Hertzel, The Big Red Machine (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1976), 101.

10 Mark Frost, Game Six. Cincinnati, Boston, and the 1975 World Series: The Triumph of America’s Pastime (New York: Hyperion, 2009), 231.

11 Sports Illustrated, November 3, 1975.

12 Hertzel, The Big Red Machine, 102.

13 The Sporting News, October 16, 1976.

14 Hertzel, The Big Red Machine, 100.

15 Posnanski, The Machine, 166.

16 Tim Wendell, High Heat (Boston: Da Capo Press, 2010), 53.

17 Darryl Smith and Lee May, Making the Big Red Machine (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2009), 209.

18 Frost, Game Six, 242.

19 Hertzel, The Big Red Machine, 21.

20 The Sporting News, January 24, 1976.

21 Dave Zeman and David Nemec, The Baseball Rookies Encylopedia (Dulles, Virginia: Potomac, 2004).

22 Miami News, January 25, 1977.

23 Smith and May, Making the Big Red Machine, 264.

24 The Deseret News (Salt Lake City), August 1, 1977.

25 The Sporting News, May 20, 1978.

26 Richard Bradley, The Greatest Game (New York: Free Press, 2009), 139.

27 The Sporting News, March 31, 1979.

28 William C. Kashatus, Almost a Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the 1980 Phillies (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 166.

Full Name

Rawlins Jackson Eastwick

Born

October 24, 1950 at Camden, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.