Clyde Day

Pea Ridge Day was a big, strong Arkansas farmboy. If he hadn’t already had a colorful nickname denoting his hometown, he surely would have been dubbed Rube. Despite his entries in the baseball encyclopedias, Clyde Day wasn’t born in Pea Ridge, or Arkansas for that matter. Day grew up in Pea Ridge, though, and brought perhaps the most national attention to the remote town in northern Arkansas since the Battle of Pea Ridge in March 1862 during the Civil War.

Pea Ridge Day was a big, strong Arkansas farmboy. If he hadn’t already had a colorful nickname denoting his hometown, he surely would have been dubbed Rube. Despite his entries in the baseball encyclopedias, Clyde Day wasn’t born in Pea Ridge, or Arkansas for that matter. Day grew up in Pea Ridge, though, and brought perhaps the most national attention to the remote town in northern Arkansas since the Battle of Pea Ridge in March 1862 during the Civil War.

Despite his mediocre record, Day was known for a lot of things during his baseball career. He brought fame of a sort to his hometown. Nary a newspaper article could be found during his career that didn’t note where he hailed from. Sportswriters were seemingly in love with the sound of the phrase “Pea Ridge.” They also loved to note the fact that Day bounced around organized baseball from one team to another. At times the tally became hard to keep. The real legend of Pea Ridge Day, though, stems from the man’s personality. He was one of the most colorful characters of his era, or any era for that matter, often compared in print to Rube Waddell. Perhaps it seemed apt that Day was one of the few pitchers to throw a screwball.

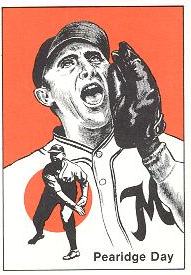

If sportswriters loved to type “Pea Ridge,” they were absolutely enamored with printing descriptions of the “Hog Calling Pitcher.” After strikeouts or other advantageous events on the diamond, Day would strike a pose on the mound and bellow out a prolonged hog call or other such screech. It became so annoying that league presidents asked him to refrain from such antics while he was on the mound. That didn’t stop him from whooping it up while he was on the bench or — in an opponent’s nightmare — from whistling or screaming taunts while in the coach’s box. The fans, though, loved every little hoot and holler. They would chant “P-e-a R-i-d-g-e,” just to rile him up during a lull in the game.

Things didn’t end well for Clyde Day, though. He developed bone chips in his elbow and seemingly overnight lost the ability to pitch at a professional level. As a result, he sank into depression and into a liquor bottle. On a March night in 1934, Day pulled out a hunting knife and slashed his throat. The 34-year-old father of a newborn fell dead in a friend’s apartment.

In parts of four seasons in the majors with three clubs, Day pitched a total of 122 innings in nine starts and 37 relief appearances, amassing an ordinary 5-7 record with a 5.30 earned-run average. Day relied on a screwball and had decent speed on his fastball, but possessed an unimpressive curveball. For a time in the minors, he also experimented with throwing ambidextrously. Al Lopez, who caught Day on the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1931, said of Day, “He was a character, big barrel-chested guy. Had a helluva screwball, never could pitch, though.”

Day was fun-loving and carefree, with a personality honed in “the wilds of Arkansas.” Like many a country boy, he loved the outdoors, especially hunting and fishing. He normally didn’t use a rifle or reel, though. He preferred to catch his fish and game with a bow and arrow, becoming proficient in making his own weapons and in utilizing them to snare fish and small game. Day would often slip away during the baseball season for a day or two to return to Pea Ridge for a little outdoor activity and to tend to his strawberry farm. Day was decent sized, about 6 feet and 190 pounds, and possessed a strong build chiseled from his days working on the farm. He continually bragged about being the strongest man in professional baseball. Day would wrap a belt around his chest, fasten it and then expand his lungs so that the belt buckle would break from the leather. His boasting led him to playfully clash with the biggest braggart in the game, Art Shires, the self-professed “Art the Great.” The two scheduled a boxing match for February 1, 1930, in Kansas City, but the bout never took place because the National Boxing Commission suspended Shires’ license in January for allegedly throwing a previous match.

Day made his reputation, though, for his stunts on the field. A newspaper said of him, “Pea Ridge has more color than a funny name. He is a hog caller. He made so much noise yelling, even when he was pitching, that the umpires and players protested.” Day would hoot, holler, or break into a prolonged hog call while on the mound after a strikeout or other key play. During particularly tense moments in the game, he would cut the tension with one of his spontaneous eruptions. Pretty soon, though, the leagues were asking him to knock off such antics while he was on the mound. He acquiesced for the most part, but then stepped up his outbursts while he was on the bench to distract opposing pitchers, batters, and fielders. Day even fashioned a whistle out of elm and blew on it until all were seething. At times Day’s minor-league managers also had him coaching on the basepaths to hoot and otherwise taunt opposing pitchers. The fans loved it. But the participants in the game, even his teammates, grew weary of the antics. As colorful as the hog calls were, the high-pitched whistling was often too much to take.

Contrary to popular belief, Henry Clyde Day did not hail from Pea Ridge, Arkansas, at least originally. He was born on August 26, 1899, in the town of Center in McDonald County, Missouri, near the borders of Arkansas and Oklahoma. Center (not to be confused with another town named Center in the northeastern part of the state, near Hannibal) was the hometown of his father, James Day. His mother, Elizabeth, or Lizzie, was from Arkansas. The family had moved to Benton County, Arkansas, the location of Pea Ridge, by 1907. James Day had worked a farm since his childhood; he continued to do so both in Missouri and Arkansas as an adult. James and Lizzie were married in 1892. They had three children born in Missouri: Lemmie, born in 1895, Henry, born in 1899, and another child who died young. In Arkansas, they had three more children Maude and Claude, twins born in 1907, and Pebble, born around 1912. The man we know as Pea Ridge was called Clyde from a young age, though his given name was Henry.

Clyde and his brother Lemmie loved playing baseball when they weren’t working the family farm. Both brothers were listed as partners on the farm in the 1920 U.S. Census. The boys learned to throw by tossing rocks at birds and “varmints.” They became well-known throughout the area for their pitching skills. Many claimed that Lemmie, four years older, was actually the better of the two. They played amateur and semipro ball throughout Benton County, sometimes on the same team, sometimes as opponents. They played with the Rogers club, managed by local baseball enthusiast Doc Buckley. Clyde, with a wicked screwball, was the one who broke into professional baseball. (Throughout his time in organized baseball, he continued to play with local Arkansas clubs, including Rogers, in the late fall and winter.)

In 1922, Day entered professional baseball with nearby Fort Smith, Arkansas, in the Class C Western Association. He appeared in 30 games, posting a 4-13 record in 173 innings pitched. The following year, he pitched for Joplin, Missouri, in the same league, managed by Gabby Street. In 43 games and 326 innings Day won 19 games with 14 losses. He rejoined Street in 1924, this time with Muskogee, Oklahoma, again in the Western Association. He led the league with 28 victories, against 17 losses, in innings pitched with a whopping 377, and in shutouts. In 50 games he posted a 3.56 ERA. Moving up to Syracuse of the International League in 1925, he appeared in only 26 games (10-9 record) but gained a bit of a reputation for pitching in both games of doubleheaders. On July 19 he won both games against Jersey City; however, he lost as well, two games to Toronto on another day. Day also gained a reputation in the minors for being weak at fielding bunts.

The St. Louis Cardinals purchased Day from Muskogee in September 1924. He made his major-league debut on the 19th, at the age of 25, tossing a six-hit, complete-game victory over the Boston Braves and allowing only one run in the 4-1 win. He started two more games that season. On the 23rd, he pitched seven innings without a decision; the Cardinals pulled out the victory in the tenth inning. On September 28, Day lost the final game of the season, 8-2 to Cincinnati, to finish with a 1-1 record. The next year, 1925, he appeared in 17 games for the Cardinals, starting only four. In 40 innings he posted a meager 2-4 record with a 6.30 ERA. On June 22, he was traded with outfielder Chick Hafey to Syracuse of the International League for left-handed pitcher Art Reinhart. Hafey was recalled by St. Louis a month later, but Day remained in the minors. On September 19, he pitched the fastest game of the year. It took him only 65 minutes to shut out Rochester, 3-0, without striking out a batter. Day finished the season at Syracuse with a 10-9 record in 26 games.

In October, Day was drafted by the Cincinnati Reds. He stuck with the team through spring training, but was gone after only about three weeks. In four games in relief, Day had no won-lost record and gave up six earned runs in 7 1/3 innings. On May 6, the Reds sold him to the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League. The Angels won the PCL pennant with a 121-81 record. Day’s record wasn’t as impressive; in 41 appearances he posted a 6-11 record with a 3.66 earned run average, though he struck out 12 batters in one game. Day’s antics – he was always a character on the field – displeased Los Angeles manager Marty Krug. During one especially tense game, Day made a snide comment to liven the bench. Krug ripped into his pitcher for his lack of intensity and for not keeping his head in the game. After the season ended, Krug tried to ship Day to Portland but the deal fell through. But just before spring training, on February 23, 1927, Day was sold to Wichita of the Western League. Wichita finished in second place under Doc Crandall. Day won 13 games and lost 11.

In early 1928, Wichita sold Day to Omaha in the same league. He posted an unimpressive 17-18 record for the club. He did eat up innings, though, amassing 313 in 52 games. On September 15, the Chicago Cubs purchased Day from Omaha. When spring training began, Day was a holdout, demanding more money than the Cubs offered him. He had mailed back club president Bill Veeck Sr.’s initial contract offer unsigned. Veeck raised the salary offer twice, but Day refused to respond to either letter. Finally the Cubs had enough and shipped him to to Kansas City of the American Association.

Day’s habit of expressing himself vocally on the diamond began in 1929. He made frequent loud outbursts designed to upset his opponents’ concentration and entertain the audience. He hadn’t done so in previous summers, at least not so much that the scribes noted it. Considering the fact that he had played in parts of three previous seasons in the majors and that the sportswriters loved such a colorful story, Day’s eccentricities surely would have merited mention, probably extensively. He joined the Kansas City club in May, pitched his first game of the year on the 17th and immediately gained lasting national fame. Soon the entire country knew of the “Hog Calling Pitcher.”

After striking out a batter or at the end of each half-inning or any time he felt like it, Day would strike a pose on the mound and let out a screeching yell or a hog call. He would also scream or hog call while not on the mound to upset opposing pitchers or batters. Naturally, no opponents cared for this; neither did the umpires, and after a while neither did his teammates. The matter was brought before American Association president Tom Hickey by the end of May. Day confessed to the league president that he was a champion hog caller in his youth in Pea Ridge; he also claimed that he couldn’t contain his enthusiasm, the whoops just poured out of him. Though Hickey admitted there was no rule against Day’s behavior, he asked the pitcher to refrain from the hooting while he was on the mound. Day agreed to perform his act only from the bench during the game and not until until after the last out of the game while he was on the mound. The Kansas City club that year turned in one of the top performances in minor-league history, capturing the pennant with a 111-56 record. Day posted a 12-5 record for the club and finished second in the league with a 2.98 ERA. Max Thomas, who would figure into Day’s story later, led the club with 18 victories. Kansas City defeated Rochester of the International League five games to four in the Little World Series in 1929. Day pitched in six of the games, five in relief. He lost two games but triumphantly was declared the victor in the ninth and deciding contest.

He returned to Kansas City in 1930; the club didn’t fare as well, though, falling to fifth place with a mediocre 75-79 record. Day posted a 13-14 record in 37 games. In the offseason, Day was drafted by the Brooklyn Dodgers. He appeared in 22 games for the Dodgers in 1931, all but two in relief, and had a 2-2 record with a 4.55 ERA.

Four days before the 1932 season opened, the Dodgers, needing a first baseman because Del Bissonette was out after arm surgery, shipped Day to the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association for veteran first sacker and future Hall of Famer George “Highpockets” Kelly. Minneapolis, under manager Donie Bush, won 100 games and the pennant. Day appeared in 37 games, posting a 9-8 record in 145 innings. However, he developed arm trouble that season, bone chips in his pitching elbow that never went away. He was placed on the inactive list on August 24 but returned at the end of the season to pitch in the Little World Series against the Newark Bears of the International League. The Bears won in six games, with Day being saddled with one of the losses in his only appearance.

Day tried all winter to get his arm in shape, but it wasn’t cooperating. The bone chips were causing too much friction and pain. Minneapolis listed him on the inactive list to start the season but sold him anyway to Baltimore on April 24, 1933. Day arrived in Baltimore on the 30th and threw some balls under the watchful eye of manager Frank McGowan. He didn’t pitch well, so McGowan returned his contract to Minneapolis the next day; however, McGowan ended up using him anyway with mixed results. After six games and a 1-1 record, Day was released. By now, the typically carefree Day was stressing over the probable ending of his baseball career. He tried to get his arm in shape but it wasn’t happening. The more he failed, the more he drank. In a last-ditch effort to revive his career, Day sought treatment at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. There, he decided to undergo surgery on his pitching arm, a major endeavor for a ballplayer during the era. Day claimed he spent $10,000 for the surgery and rehabilitation. In the end it was for naught; he couldn’t regain his old form. With each passing day he became more distraught about his plight and drank more and more to cope with the anxiety.

Family tragedies over the years had increased Day’s pain. In 1922, Clyde’s older brother, Lemmie, whom he grew up idolizing and playing ball with, contracted blood poisoning. His right leg was amputated in an effort to stave off the spread of the infection. It was unsuccessful; Day’s 27-year-old brother died. In 1929, Day’s mother, Lizzie, killed herself by drinking poison. In May 1933, Day’s father died after suffering a heart attack. Day did have some good news in 1933, though, and hope for the future. After ten years of marriage, Clyde and his wife, Lois, were expecting their first child. Day was enthusiastic about the new baby and his hopes soared for a time. The child, John Charles, was born in February.

As spring of 1934 rolled around, Day feared that his days on the diamond were about to end. But he talked the San Francisco Seals into bringing him to camp. On March 18, Day, suffering from prolonged depression compounded by his drinking binges, had an argument with his wife over his insistence on leaving for the West Coast despite having a bad arm and so soon after his son was born. Day then left for San Francisco but first stopped in Kansas City first to visit with his former Kansas City teammate Max Thomas. By the time Day arrived in Kansas City, on March 21, he wasn’t feeling well, complaining of “lapses in memory.” Thomas took him to the hospital, where a doctor advised Day to rest a few days before going on to San Francisco. Thomas took Day back to his apartment. There, said Thomas, “He was unpacking a bag when I stepped out of the room a minute. When I returned he was in a small closet. He stepped out with a hunting knife and slashed his throat. I tried to stop him but he brushed me aside.”

Clyde Day was dead at the age of 34. His wife fainted upon hearing the news and was taken to a hospital. More than 500 mourners attended Day’s funeral at the Pea Ridge Baptist Church on the 23rd. He was buried in Pea Ridge Cemetery.

Sources

Ancestry.com

Baseball Magazine, February 1998

Charleston Gazette, West Virginia

Chicago Tribune

Christian Science Monitor

Constitution Tribune, Chillicothe, Missouri

Daily Mail, Hagerstown, Maryland

Decatur Daily Review, Illinois

Evening Huronite, Huron, South Dakota

Evening Independent, Massillon, Ohio

Evening State Journal and Lincoln Daily News, Nebraska

Evening Tribune, Albert Lea, Minnesota

Fayetteville Daily Democrat, Arkansas

Findagrave.com

Fresno Bee

Galveston Daily News

Hartford Courant

Kingsport Times, Tennessee

Lima News, Ohio

Los Angeles Times

Minorleaguebaseball.com

Moberly Monitor-Index, Missouri

New York Times

Oakland Tribune

Port Arthur News, Texas

Sabrwebs.com

Salt Lake Tribune

San Antonio Express

Stevens Point Daily Journal, Wisconsin

Stewthornley.net

Syracuse Herald

The Sporting News

Full Name

Henry Clyde Day

Born

August 25, 1899 at Center, MO (USA)

Died

March 21, 1934 at Kansas City, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.