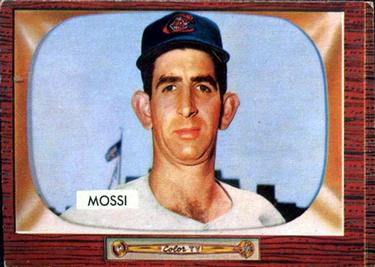

Don Mossi

One of the rarest things in baseball is a shut-down righty-lefty bullpen. Players, managers, and – let’s face it – agents, like relief roles defined. Today you have eighth-inning guys and ninth-inning guys. And if you’re lucky, you have hurlers who can form a human bridge from the starters to those players. Having two closers—one to dispose of lefties, another to clamp down on righties—is either an unheard-of or unaffordable luxury. The short list includes Eastwick & McEnaney, Gossage & Lyle, Hernandez & Lopez, and Dibble & Myers. From there you have to think really hard. Of course, fans of the Cleveland Indians can tell you who the originals were: Don Mossi and Ray Narleski, rookie roommates on the fabled 1954 American League champions.

One of the rarest things in baseball is a shut-down righty-lefty bullpen. Players, managers, and – let’s face it – agents, like relief roles defined. Today you have eighth-inning guys and ninth-inning guys. And if you’re lucky, you have hurlers who can form a human bridge from the starters to those players. Having two closers—one to dispose of lefties, another to clamp down on righties—is either an unheard-of or unaffordable luxury. The short list includes Eastwick & McEnaney, Gossage & Lyle, Hernandez & Lopez, and Dibble & Myers. From there you have to think really hard. Of course, fans of the Cleveland Indians can tell you who the originals were: Don Mossi and Ray Narleski, rookie roommates on the fabled 1954 American League champions.

Narleski, the flamethrower, didn’t survive the 1950s. Mossi, the control artist, was a different story. He not only had a grand career as a reliever, he was a top starter for several seasons, too, and was still getting batters out in 1965. As memorable for his peculiar looks as his pinpoint pitching, Don was the kind of guy every manager wanted on the team.

Donald Louis Mossi was born on January 11, 1929, in St. Helena, California, in Sonoma County, north of San Francisco. He grew up in Daly City, just south of San Francisco, and attended Jefferson High School. Like many other schools in the Bay Area, “Jeff” would produce several outstanding athletes and sports personalities—including major leaguers Ken Reitz and Tony Solaita, and NFL coaching legend John Madden.

During the summers Don played on youth-league teams, typically made up of his schoolmates and neighborhood kids. He threw hard, hid the ball well, and had a lot of poise for a young left-hander.

The Cleveland Indians signed Mossi after his 19th birthday and assigned him to the Bakersfield Indians of the Class C California League for the 1949 season. Bakersfield may have seemed miles away from the majors, but Mossi’s spirits must have been buoyed by the knowledge that three seasons earlier, Mike Garcia had toiled for these same Indians. Now he was elbowing his way into the Cleveland rotation.

Manager Harry Griswold guided Bakersfield to a first-place finish with an 85-54 record, largely on the strength of the league’s top player, Earl Escalante. Escalante won 28 games—ten more than anyone else in the loop—and provided a veteran presence for Mossi and the team’s other young pitchers. Bakersfield’s season ended when they lost in the first round of the playoffs. Mossi won 13 games and lost 9, fanning 149 California League hitters in 195 innings. He projected as a strikeout pitcher, which made his 115 walks a matter of concern.

Mossi returned to Bakersfield in 1950. The Indians finished the year 61-79, in sixth place. Mossi went 11-10 in 29 starts. His control issues were still present, but there was little else to complain about. As a 21-year-old lefty he was making progress and getting critically important innings under his belt.

In 1951 Mossi began with the Wichita Indians of the Class A Western League. Although he still struggled with bouts of wildness, he had refined his approach considerably, as witnessed by his 2.29 ERA in 122 innings. He went 7-6 for Wichita and also pitched for Wilkes-Barre of the Eastern League, where he was equally effective in six appearances.

In 1952 Mossi was assigned to Dallas of the Double-A Texas League. One of five starting pitchers on the Eagles, he was a swingman in the four-man rotation logging 42 appearances with 22 starts, and went 9-8 in 179 innings with a 3.42 ERA against the stiffer competition. He was still walking a batter every other inning.

The 1953 season was a pivotal one for Mossi. He found himself back in the Texas League, this time with the Tulsa Oilers, a Cincinnati Reds farm team. The Indians no longer had an affiliate agreement with Dallas, and Mossi was one of many Cleveland players at this level to be sprinkled around the minors. Recognizing Mossi’s resiliency, manager Joe Schultz used him liberally in 1953. Mossi led the team in innings pitched with 201, going 12-12 with an ERA under 3.00. Lost in these statistics was the fact that he effected a significant change in his pitching style at Tulsa. He began experimenting with a three-finger grip instead of the traditional two, and found he could spot the ball without losing velocity or movement. This discovery could not have come at a better time, for the rules of Organized Baseball dictated that the Indians either had to promote Mossi to the majors in 1954 or waive him, for he had spent his fifth season in the minors.

Thus Mossi found himself in spring training with the Indians in 1954, pitching for a spot on the big-league roster. Among the pitchers in camp were starters Mike Garcia, Early Wynn, and Bob Lemon. Among them they totaled 56 victories in 1953. Bob Feller, who at 35 no longer had his blinding speed, still had a killer curve and brought nearly two decades of professional mound experience to the fifth starter’s job. The question for manager Al Lopez was who would get the fourth starter’s role. The most likely candidates included Dave Hoskins, Bill Wight, Bob Hooper, rookie Dick Tomanek, and Art Houtteman. Mossi was never mentioned among the competitors for a rotation spot. He was pitching for his baseball life, and when he arrived at camp and saw the wealth of arms on the Cleveland roster, he literally started thinking about a second career. During the winters he had been working construction to support himself and his wife, Eunice, whom he had married in the summer of 1950. He showed a flair for carpentry and decided this would make a fine fallback profession. With the Indians he didn’t have a particularly outstanding spring, but Indians manager Al Lopez was a shrewd judge of potential, and saw that Mossi had mostly licked his control problems, had a good fastball, and could clearly throw his curve for strikes. Both pitches were well above average for a rookie. To Lopez, keeping a competent two-pitch pitcher like Mossi in the bullpen was for more appealing than the prospect of letting him go.

As the season began, the Indians faced the prospect of unseating the New York Yankees, who had won the pennant (and World Series) every year since Casey Stengel assumed the helm in 1949. The experts were predicting that the Yankees would finish on top again in 1954 with the. Indians in third place. In ’53 the Indians had a 92-win season, which left the Tribe seven wins short of New York. Lopez knew that his club could not think seriously about breaking the Yankees’ death grip on first place without winning at least 100 games. To gain those extra victories, Cleveland had to improve in three areas: the infield, the outfield, and the bullpen. In the infield, Cleveland had the talent to do so, with the exception of first base, which was manned by light-hitting Bill Glynn. Six weeks into the season they swung a deal with the Baltimore Orioles for the streaky but powerful Vic Wertz, a 29-year-old lefty who had once been an All-Star with Detroit. Second baseman Bobby Avila enjoyed a career year, batting a league-leading .341. Wertz, Avila, reigning MVP Al Rosen at third base, and talented glove man George Strickland gave the Indians a superb inner defense.

The Cleveland outfield featured clutch-hitting Larry Doby, but from there the starting situation was unclear. The incumbents after Doby were Wally Westlake and Dale Mitchell, both in their 30s. Harry Simpson failed to impress and was sent to the minors. This opened the door for Al Smith, a patient hitter who could play multiple positions, and Dave Philley, a switch-hitting journeyman who today would be called a “professional hitter.” Philley hit just well enough to allow Lopez to spot Westlake off the bench. Smith did a terrific job batting at the top of the lineup with Avila.

That left the bullpen. Former catcher Lopez understood that left-handed hurlers were more effective against left-handed batters, and that right-handed pitchers did better against right-handed hitters. This was hardly revelatory information, but few managers until then were willing to build and then utilize a bullpen around this concept. The 1953 Indians had not had the arms to make this happen, particularly from the left side. The 1954 Indians did. Mossi joined veteran Hal Newhouser, signed by GM Hank Greenberg after being released by the Tigers, as the two southpaws in the Cleveland relief corps. Future Hall of Famer Newhouser performed in long relief for the Indians in 1954. Mossi, with his fastball and curve, newly minted pinpoint control, and ability to hide the ball from batters, functioned as the short man and sometimes-starter when Cleveland faced a tough left-handed lineup, or when Feller or Houtteman was unable to go.

The right-handed half of the bullpen was made up of Mossi’s former minor-league teammates Dave Hoskins and Bob Hooper, along with Garcia, who warmed up quickly and could be used in emergencies. The man who stepped up and seized the mantle of short relief was fellow rookie Ray Narleski. The skinny New Jerseyan was a second-generation major leaguer. He had climbed the organizational ladder a step ahead of Don, but here they were, asked to close out the games that the previous year’s bullpen had allowed to slip away. Narleski threw a white-hot fastball that enemy hitters found irresistible. He would take opponents up the ladder until they were swinging at pitches out of the zone, and either striking out or hitting harmless flies. Mossi and Narleski roomed together during the 1954 campaign.

Handling the pitching staff was Jim Hegan, a light-hitting 34-year-old veteran who had been playing in the Indians’ system since the 1930s.

Mossi may not have let it show, but going into his first big-league campaign, surrounded by superstars and awash in impossibly high expectations, he was downright scared. He later said that the team’s veterans helped him find his comfort zone, particularly Lemon and Feller. Of course, there wasn’t much time for him to ponder his surroundings. The Tigers and White Sox got off to blistering starts, while Cleveland found itself in the cellar after nine games.

An 11-game winning streak in May enabled the Indians to claw their way to the top of the standings, where they proceeded to engage in a spirited battle with the White Sox and Yankees for much of the summer. On June 12 the Indians returned to the top of the standings and, with the exception of a brief moment in mid-July between games of a doubleheader, that is where they stayed until the end of the season, finishing with a league-record-shattering 111 victories. The Indians shook off the White Sox in early July, when they beat Chicago in four consecutive one-run games at Municipal Stadium. The Yankees were harder to shake, but the Indians left them for good on September 12, when they took both ends of a Sunday doubleheader in front of a record 86,563 cheering fans. At season’s end, the Tribe ended up eight games in front of the Yankees who, ironically, topped 100 wins for the first time during the Stengel regime.

Mossi finished the year with a 6-1 record in 40 appearances, 35 of them in relief. He finished 16 games as a reliever, seven of which qualified as saves (which were not a statistic in those days). In his five starts, Mossi went 2-1 and pitched two complete games. His only loss as a starter was inflicted by the Tigers in extra innings. In all, he hurled 93 innings, gave up 56 hits and walked 39 batters. He struck out 55 and turned in an excellent 1.94 ERA, contributing to the team’s league-best 2.78 mark. Narleski was just as good, finishing 19 games with 13 saves and a 2.22 ERA.

The 1954 World Series was a watershed moment for baseball, though for reasons largely untold. For the first time, baseball fans were talking about the battle of the bullpens. Other pennant winners had relied on good relief pitching, but never before had two opponents in the fall classic boasted such impressive bullpens. Hoyt Wilhelm and Marv Grissom combined for 22 wins and 26 saves for the Giants, more than a match for the 16 wins and 27 saves shared by Mossi, Narleski, and Newhouser. As for Mossi, his role heading into the Series seemed clear. He would be used to quell the left-handed bats of Don Mueller, Whitey Lockman, and Hank Thompson.

In Game One, with the score tied 2-2, Mossi and his teammates watched Willie Mays reel in Vic Wertz’s eighth-inning drive to deep center field, a play that turned out to be pivotal and famous. With a scoring opportunity lost, the Indians were focused on holding the Giants. In the tenth inning, starter Bob Lemon walked Mays, who stole second. Lemon issued an intentional pass to Thompson to create a force with one out.

Were the year 2004 instead of 1954, Mossi might have been inserted in the game to face left-handed pinch-hitter Dusty Rhodes. Instead, Lopez left the right-handed Lemon on the mound, hoping he would induce a grounder for a double play. Rhodes homered to win the game.

Mossi saw action in the final three games of New York’s jaw-dropping four-game sweep. In Game Two, one inning after Rhodes homered against Early Wynn in the seventh, Mossi took the mound and retired Lockman on a foul pop to first, Alvin Dark on a liner to second, and Thompson on a comebacker. The Indians put the first two runners on in the top of the ninth, but Johnny Antonelli retired the next three to preserve a 3-1 victory.

The Series switched to Cleveland for Game Three, but the Indians’ luck failed to change. For the third contest in a row, Rhodes got the backbreaking hit, this one a two-run pinch single off of Art Houtteman in the third inning. Mossi took the mound in the ninth to mop up a 6-2 loss. He gave up two hits, but retired the Giants with a double play and a strikeout of Rhodes, who had stayed in the game.

Game Four was a rout, with the Giants touching Lemon, Newhouser, and Narleski for four runs in the fifth inning to open a 7-0 lead. Mossi pitched the sixth and seventh, retiring six straight hitters as his teammates scored three times to make the game interesting. In the bottom of the seventh, Lopez lifted Mossi for Rudy Regalado, whose single to center cut the deficit to 7-4. Manager Leo Durocher brought Hoyt Wilhelm into the game, and he retired Dave Pope on a comebacker to end the inning. Antonelli, the Game Two starter, followed Wilhelm and finished off the Indians without allowing another run.

In four World Series innings, Mossi allowed a couple of screamers, but held the Giants scoreless in his three appearances. Cleveland fans were left to wonder what might have been had Lopez matched Durocher lefty for lefty at the three key moments during the Series. Mossi’s assessment of the Indians’ loss was simple: “We were overconfident.”

The law of gravity seized the Indians in 1955, as they finished with 93 wins—three behind the Yankees. With the exception of Al Smith, none of the hitters could reproduce his 1954 numbers. Nor could the Big Three, though Lemon tied for the AL lead with 18 wins. Lemon, Wynn and Garcia accumulated 46 victories—19 fewer than the year before. Needless to say, Lopez counted more heavily on his bullpen, and once again Mossi and Narleski answered the call. They made 57 and 60 appearances, respectively and combined for 13 wins and 28 saves. Mossi was sharp all year. In 81⅔ innings he gave up 81 hits, while he walked a meager 18 batters. He struck out 69 and had a 2.42 ERA to go with four wins and nine saves. Herb Score, the rookie starter who won 16 games for the Indians that summer—and called games on TV and radio for decades—said often that he never saw a better lefty-righty duo than Mossi and Narleski in 1955. At season’s end, Mossi even received a handful of MVP votes from the baseball writers.

An elbow injury nagged Narleski for much of the following season, as the Indians finished behind the Yankees in the pennant race yet again. Mossi finished 24 games, winning 6 and saving 11 in support of Wynn, Lemon, and Score, who won 20 games each. His ERA rose to 3.59, but his other numbers stayed more or less the same.

The 1957 season saw the departure of Al Lopez to the White Sox. Chicago ascended to second place while Cleveland, under Kerby Farrell, finished a game below .500, in sixth place. The starting staff disintegrated due to age and injury, the most notable event being the Gil McDougald line drive that destroyed Score’s career. With Cleveland’s acquisition of Hoyt Wilhelm, Farrell pressed Mossi into action as a starter 22 times in 1957. He responded with six complete games and a shutout. He went 11-10 with a pair of saves and an uncharacteristically high 4.13 ERA.

That July Mossi was selected to play in his one and only All-Star Game. Called in to preserve a 6-4 lead in the ninth inning with two on and none out, he struck out Eddie Mathews looking, then allowed a ground single to left by Ernie Banks that plated a run. Gus Bell, running from first base, was thrown out trying to reach third base for the second out. Gil Hodges entered the game as a pinch-hitter and Bob Grim of the Yankees replaced Mossi. Hodges hit a liner to left, which Minnie Minoso snagged to end the game. After his All-Star appearance, Mossi had a rough July, dropping five straight at one point and getting roughed up by Senators, Yankees, and Red Sox.

Mossi returned to the bullpen in 1958, as the Indians brought in a passel of new starters, including Mudcat Grant, Gary Bell, and Cal McLish. The new-look Tribe improved by exactly one win, finishing a game over .500, in fourth place. Mossi contributed seven wins and three saves, assuming more finishing duties after Wilhelm was waived and picked up by the Orioles.

Mossi had actually enjoyed his time as a starter in 1957, and although he helped make history with his relief work in 1954, he was never entirely comfortable going game to game without knowing if he’d be working or not. Thus when the Indians dealt Mossi, Narleski, and infielder Ossie Alvarez to Detroit for Billy Martin and Al Cicotte prior to the 1959 season, Don looked forward to the change of scenery. There he was reunited with a former minor-league manager, Bill Norman, and joined a starting staff that included Frank Lary, Jim Bunning, and Paul Foytack. The season got off to a disastrous start, as the Tigers limped to a 2-15 record. Norman was replaced with Jimmy Dykes and the ship was righted, as the Tigers went 74-63 the rest of the way. To the amazement of Tiger fans, Mossi turned out to be the star of the staff. He went 17-9, hurling 228 innings, giving up 210 hits and walking 49. He tied for the team lead with three shutouts and tied with Milt Pappas for second in the American League with 15 complete games.

The highlight of the year for Mossi was his five straight wins over New York. He and Lary, the famous “Yankee Killer,” were a major reason why the Bronx Bombers slipped into third place. Mossi actually preferred facing slugging lineups to teams that scratched out hits. He succeeded by changing speeds and locations and upsetting the timing of enemy hitters. Mickey Mantle, Elston Howard, and Bill Skowron were much easier for him to deal with than, say, Nellie Fox and Luis Aparicio. Besides, by that point, Mossi had lost a little off his fastball and was starting to feel the arm discomfort that would accompany him the rest of his career. Blowing the ball past power hitters wasn’t really an option anymore. In fact, he had started working a changeup into the mix, if only to create the illusion of speed when he fired a fastball over the plate.

Mossi began the 1960 campaign by beating the Yankees twice more, running his personal string to seven. He completed 9 of 22 starts and had a 9-8 record when a sore arm ended his season in late August. The Tigers finished a disappointing 71-83, in sixth place. The team’s pitching returned to form in 1961, as Lary won 23 games and Jim Bunning added 17. Mossi bounced back with a 15-7 mark during a relatively pain-free season, as he logged 240 innings and led the starters with a 2.96 ERA. The Tigers held first place for most of the first half, but relinquished their grip after the All-Star break to the Yankees. New York took the pennant with 109 wins to second-place Detroit’s 101. If Mossi ever wondered how the Yankees felt the year Cleveland won 111, now he knew. Sometimes, it just wasn’t your year.

By this time Mossi had appeared on enough bubble-gum cards to have caught the attention of millions of young fans, who marveled at his unusual visage. He did not have the classic country-boy good looks of a Mickey Mantle or the dark, handsome face of a Sandy Koufax. Don was, well, different. He had a long, slightly crooked nose, his eyes were close together, and his ears stuck out to the edges of the cardboard. Indeed, some of his teammates called him Ears. Others nicknamed him The Sphinx. Later, when these young fans grew up, they were less diplomatic. One said he looked like “Mount Rushmore on a rainy day.” Bill James wrote that Don was the “complete ugly player. He could run ugly, hit ugly, throw ugly, field ugly, and ugly for power. He was ugly to all fields.”

Well, Don could certainly win ugly. During that remarkable 1961 season, for instance, he proved it in a June game against the Indians. His former teammates launched no fewer than five home runs off him, yet he persevered and won the game. It took 38 years for another Tiger, Jeff Weaver, to match Mossi’s team record by allowing five dingers against the Boston Red Sox.

Alas, Detroit’s aging rotation could not maintain its high standards in 1962, and the team sank to fourth place with an 85-76 record. Mossi, now 33 years old, made 27 starts and won 11 times against 13 defeats, with a 4.19 ERA. That wonderful 1961 season was starting to look like his last hurrah as a starter. This proved to be the case, as 22-year-old Mickey Lolich usurped Mossi’s spot in the rotation during the 1963 campaign. Don finished his 10th year in the majors with a 7-7 record and a 3.74 ERA. No one was complaining about his control—he walked just 17 batters in 123 innings—but as far as the Tigers were concerned, he was nearing the end of the line.

Mossi reported to spring training in 1964 to find the Tigers were committed to dismantling their entire starting staff. He was sold to the White Sox in March—a vertical move, given Chicago’s second-place finish the year before, and the fact that he would be reunited with Al Lopez. A fringe benefit of this arrangement was the chance to work with Ray Berres, the team’s pitching coach. Berres was known for coaxing quality innings out of tired arms. Mossi and Frank Bauman served as the lefties in the Chicago bullpen during an enthralling summer. Hoyt Wilhelm was the team’s primary closer, but Mossi got to finish 17 games, picking up seven saves in the process. The White Sox, Orioles, and Yankees spent the summer in a death struggle for first place.

Mossi’s season ended before the September stretch run began thanks to his recurring arm trouble. The White Sox finished one game behind New York. In a season of what-ifs for South Side fans, having a healthy Don Mossi available might have been one of the difference makers the team needed.

The White Sox released Mossi after the 1964 season. He caught on with the Kansas City A’s the following spring. Although the team finished dead last with 103 losses, and Mossi’s arm hurt almost all the time, he cherished his last summer as a big leaguer. In an effort to qualify Satchel Paige for a pension, owner Charles Finley signed him and planted him in the bullpen until he had enough days under his belt. Paige, who was pushing 60 at the time, regaled the relievers with fables from his Negro League days.

Mossi felt old and out of place in the youthful Kansas City clubhouse. His kids weren’t much younger than his catcher, Rene Lachemann, or fellow pitcher Catfish Hunter. He threw his final pitch on October 1 against the White Sox, giving up the winning runs in a meaningless ballgame. His last big-league season ended with 5 wins and 7 saves, and a 3.74 ERA in 51 relief appearances.

That winter Finley sent Mossi a new contract, but he never signed it, choosing to retire instead. His final career numbers were 101 wins, 80 losses, and 50 saves. He completed one-third of his 165 starts, and made 295 relief appearances. In 1,548 innings, he allowed 1,493 hits, walked 385, and fanned 932 batters. His career ERA was 3.43. Though never recognized for his defense, he handled 311 chances while committing just three errors. His .990 fielding percentage was the best in history at the time he retired.

Life after baseball mostly meant life without baseball. Mossi watched the occasional game on television and once appeared at a Giants Old Timer’s Day at the behest of his old teammate, Al Rosen. Mossi coached some youth teams. Otherwise, his contact with baseball was minimal. He received a fair number of letters and autographs from fans at his home in Ukiah, about three hours north of San Francisco. When fans sent him an extra card, he would set it aside for his grandchildren.

Over the years, when team physicians examined Mossi’s slightly crooked arm, they surmised that he must have suffered an accident as a child. He could not remember one. If an accident did occur, it was a happy one. For Don Mossi could hurl a baseball with the best of them.

This biography is included in the book Pitching to the Pennant: The 1954 Cleveland Indians (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Joseph Wancho. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Sources

Books and Guides

Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Free Press, 2001)

David Neft, Richard Cohen & Michael Neft, The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball (New York: St. Martin’s Press)

Mike Shatzkin and Jim Charlton, The Ballplayers (New York: Arbor House, 1990)

John Thorn, The Relief Pitcher: Baseball’s New Hero (New York: Penguin Group, 1985)

The Sporting News Baseball Guide

The Sporting News Baseball Register

Magazines

Dell Sports Baseball Stars

Sport

Sport World

Newspapers

Chicago Sun-Times

Cleveland Plain Dealer

The New York Times

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

The Sporting News

Washington Post

Websites

Baseball-Reference.com

Baseball-Almanac.com

Other

Interview with Don Mossi by James Floto and Randy Rosenblatt, 1995

Full Name

Donald Louis Mossi

Born

January 11, 1929 at St. Helena, CA (USA)

Died

July 19, 2019 at Nampa, ID (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.