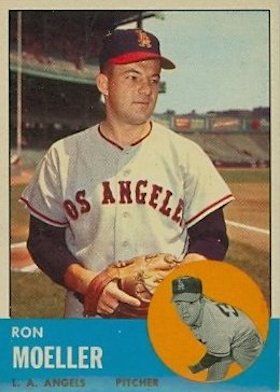

Ron Moeller

In 1962 the Los Angeles Times veteran sportswriter Braven Dyer offered in three short sentences an apt analysis of the brief career of Ron Moeller: “Moeller is something of a problem pitcher. At times, he seems to have everything. The next time out, he seems devoid of confidence.”1 Emerging on the major league stage in 1956 at the tender age of 17, “The Kid” was generally perceived as a can’t-miss prospect. Seven years later Moeller retired with an uninspiring record of 6-9, 5.78 in 152⅔ innings.

In 1962 the Los Angeles Times veteran sportswriter Braven Dyer offered in three short sentences an apt analysis of the brief career of Ron Moeller: “Moeller is something of a problem pitcher. At times, he seems to have everything. The next time out, he seems devoid of confidence.”1 Emerging on the major league stage in 1956 at the tender age of 17, “The Kid” was generally perceived as a can’t-miss prospect. Seven years later Moeller retired with an uninspiring record of 6-9, 5.78 in 152⅔ innings.

Ronald Ralph Moeller was born on October 13, 1938, to Ralph F. and Claire E. (Batter) Moeller, in Cincinnati, Ohio. He was the great-great-grandson of German immigrants Henry William and Hannah Marie Elizabeth (Menke) Möllers who arrived separately in Indiana in the first half of the 19th century. Their son Ben, a shoemaker, appears to have been the first to change the surname to Moeller. Around 1870 he gravitated the short distance to the Cincinnati region. Ben’s grandson Ralph—the ballplayer’s father—and his twin sister Ruth were born in the Queen City in 1910. Ralph initially found work as a shipping clerk for a machine shop before forging a long career as a travelling salesman. Growing up within walking distance of Cincinnati’s Crosley Field, it is believed Ralph was a devoted baseball fan. He passed this passion on to his son.

Moeller went to school just two miles west of the Reds’ famed park. Built in the 1920s, Elder High School, named after the Archbishop of Cincinnati (1883-1904), was the city’s first Catholic diocesan high school. It is renowned for the large number of professional athlete alumni. In 1955-56, during his junior and senior years, Moeller pitched a combined 12-1 record to lead the Elder Panthers to consecutive state championships.2 In 1955, he also led his US Postal Employees American Legion Post No. 216 to a national crown, posting a record of 9-0, 1.23 with 77 strikeouts in 51⅓. Though the post came up short the following year, Moeller was even more dominant: 12-1, 1.68 with 149 strikeouts in 122 innings. “[D]ubbed the leading American Legion pitcher in the country by [Baltimore] Farm Director Jim McLaughlin,”3 the Orioles wooed Moeller from a Notre Dame athletic scholarship and away from the scouts of every other major league club to sign the left-handed hurler in June 1956, shortly after his high school graduation.

Still four months removed from his 18th birthday, Moeller was assigned more than 1,000 miles south to the Lubbock (Texas) Hubbers4 in the Class B Big State League. The youngest of six teenagers in the circuit, the kid did not appear to have been intimidated by former major leaguers Monty Basgall and Sibby Sisti, both of whom were twice his age. Moeller “showed considerable promise”5 despite a meager 4-7 mark. Five of the seven losses were by one run, and he managed a 3.88 ERA in 72 innings (11 appearances, nine starts) in the high scoring league.

The Orioles were unable to contain their excitement over their 17-year-old lefty. They promoted Moeller among the late-season call-ups, and he made his major league debut on September 8, 1956 at home against the Boston Red Sox. Facing seven batters over two innings, Moeller surrendered one hit while striking out the first and last hitters faced. Excluding a run-scoring wild pitch in his next outing (the run charged to reliever Don Ferrarese) Moeller delivered 1⅔ perfect innings over two appearances to earn his first big league start on September 29 against the Washington Senators. Not nearly as sharp, Moeller yielded nine hits and two walks in five innings to suffer a loss in his first decision.

During the winter Moeller was transferred to the Orioles 40-man roster. Whether the club seriously considered moving the youngster on to the parent roster in the spring of 1957 isn’t known, but the decision was soon taken out of their hands after Moeller contracted a severe tonsil infection. Though he chose to forgo surgery to return quickly to camp, the Orioles assigned him to the Class AA San Antonio Missions in the Texas League. “[L]oaded with right-handed batters . . . [the circuit was] referred to as a graveyard for southpaw pitchers,” a fierce reputation that Moeller found not the least bit daunting. He earned the Opening Day nod over a corps of veteran hurlers and won his first four starts. “He’s got the poise of a veteran,” said Missions’ manager Joe Schultz. “You’d think he had been around for seven or eight years. That’s how much baseball sense he has.”6 Noted for his fastball, Moeller took particular pride in his curve, using it effectively on June 9 in a two-hit win over the Shreveport Sports before visiting family and friends. Exactly one month later Moeller twirled his first professional shutout, a five-hit,10-strikeout gem against the Fort Worth Cats. Though the league eventually caught up with him—he lost eight of his last 12 decision—the Texas League Baseball Writers’ Association honored Moeller with selection to the All Star team. “We’re banking on him [next year,]” said Orioles’ manager Paul Richards.7

In 1958, the Orioles embarked on a robust youth movement that eventually resulted in the franchise’s first world championship in 1966. The youth move was particularly evident in the pitching staff where Moeller was one of three 19-year-olds vying for a spot in the Orioles’ rotation. In the long run this fast-track proved beneficial to only one: Milt Pappas. Injuries spelled much of Moeller’s season (and thereafter much of his career). He was assigned to the Class AAA Vancouver Mounties in the Pacific Coast League after a sore arm sidelined him during the Orioles Arizona-based spring training camp. On May 13, after fellow 19-year-old righty Jerry Walker stumbled at the major league level, Moeller was recalled. He fared no better in limited use—4⅓ innings over 26 days—before landing on the disabled list with an ailing shoulder. His combined use between Vancouver and Baltimore was a mere 35⅓ innings for the year.

Hopes for a successful rebound remained high when, a week before spring training opened Moeller joined a premium cast of Oriole upper-tier prospects that included Bo Belinsky, Chuck Estrada and Jack Fisher among others pitchers for special instruction. But the club’s entire contingent had barely arrived on February 22, 1959, when Moeller got injured again. In April he was assigned to the Class AAA Miami Marlins in the International League and promptly placed on the disabled list. Arm problems continued to plague the 20-year-old when he was reassigned to Texas with the Class AA Amarillo Gold Sox.. He concluded his two-stop season with an uninspiring record of 6-8, 3.73 in 135 innings.

Mostly injury-free throughout the 1960 season, Moeller again started in Miami before spending the bulk of the year with Vancouver. A deceiving 8-8 record belied a 3.26 ERA as Moeller placed among the Pacific Coast League hurlers with 120 strikeouts (on the down side he also placed among the leaders in walks: 76 in 171 innings). On August 17, under the watchful eyes of Orioles scout Eddie Robinson, Moeller delivered a 2-1 complete game win over the Salt Lake City Bees. Two weeks later he twirled a four-hit, 13-2 victory against the Seattle Rainiers. Apparently Moeller was among the parent club’s September call-ups, but he did not make an appearance. Jim McLaughlin, the same farm director who declared Moeller the country’s best American Legion pitcher four years earlier, tabbed the youngster among the club’s top prospects.

But neither McLaughlin nor the Orioles would benefit from their investments. On December 14, Moeller was chosen with another Oriole pitching prospect—future Cy Young award winner Dean Chance—in the 1960 expansion draft. Los Angeles Angels had picked both, and Moeller drew the lion’s share of attention: in a nationwide poll of sportswriters he was selected as the club’s “Best Young Pitcher.”8 “[T]he former Oriole boy-wonder farmhand . . . may be a star in the making for [general manager Fred] Haney. [Manager Bill] Rigney thinks so [too] and . . . is limiting the kid to six or seven innings at [a] time to avoid strain.”9 On April 30, 1961, following four relief appearances, Moeller made his first major league start in five years. He held the Kansas City Athletics to three hits and an unearned run over six innings before an erratic streak—two walks, a single and two wild pitches—overtook him in the seventh. He did not figure in the decision in the Angels’ 6-4 win. Moeller came away with another no decision five days later after surrendering just three hits and one earned run in 6⅓ innings against the reigning AL champion New York Yankees.

On June 5, after suffering five big league losses, Moeller finally captured his first major league win, and in grand style: shutting out his former Baltimore teammates. He scattered six hits and preserved the gem after escaping a one out, bases loaded jam in the fifth by striking out future HOF Brooks Robinson and All Star first baseman Jim Gentile. The whitewash marked the Angels’ second shutout in franchise history, and Moeller became the club’s third pitcher to post a complete game. “I’d say that Paul Richards probably helped me the most with my pitching,” Moeller claimed after the game. “He took me right after I got out of high school and changed my motion.”10

The shutout—the only one of his career—proved to be Moeller’s highlight for the season. Excepting a second strong performance against the Orioles on June 24, the southpaw crumbled to a record of 1-4, 7.76 over his final 21 appearances, including a dreadful start against the Chicago White Sox on June 14 in which the lefty yielded seven runs while retiring just two batters. In September, a mere five months after raving about Moeller’s potential, general manager Haney was forced to reevaluate. “I’d say that Pitcher Ron Moeller and Outfielder Chuck Tanner are fringe players. We don’t know for sure about their futures.”11 In Moeller’s case any such evaluation would have to be deferred for more than a year after he was called into active service with the US Army. Then a knee injury he suffered while in service delayed an anticipated August 1962 return further.

The 1963 season was Moeller’s last in the major leagues. A solid spring training yielded to a disappointing season start—three uninspiring relief appearances—and a quick demotion to the Class AAA Hawaii Islanders in the PCL. On May 27, Moeller delivered a four-hit shutout against the Salt Lake City Bees. And a month later he was deprived of another whitewash—this time against the Dallas-Fort Worth Rangers—when his teammates’ fielding miscues resulted in an unearned run. On July 9 the Washington Senators, who had the worst pitching staff in the majors, purchased Moeller’s contract. But he couldn’t appear in the rotation until August 15 because of an arm injury he’d sustained days before the purchase. Six days later he beat the Athletics and, on September 25, captured his last major league victory, a 6-2 win over the Detroit Tigers. It was also his last big league appearance. The Senators released him in October. He attended their camp the following spring as a non-roster invitee and was assigned to the Class AA York (Pennsylvania) White Roses in the Eastern League. Moeller was subsequently released in May without making an appearance.

The prior November Moeller married Cincinnati native Arleen Gleason in the small city of Mt. Healthy, Ohio. The union produced two children. Moeller found work with an automotive products company and eventually was promoted to sales manager. He died on November 2, 2009, one month after his 71st birthday survived by his wife of 46 years, two children, and four grandchildren.

Moeller’s professional career represents the classic case of rushing a prime prospect to the majors too quickly. Lauded by sportswriters, farm directors, managers, and general managers alike, Moeller’s forecasted baseball future shined far brighter than its reality.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the Elder High School Alumni Office. Further thanks are extended to Rod Nelson, chair of the SABR Scouts Committee and Tom Schott for review and edit of the narrative.

Websites

Ancestry.com

Notes

1 “’Angels’ Fate Rests on Each of You,’ Rig Tells Twirling Staff,” The Sporting News, February 16, 1963.

2 “1956 State Baseball Champions,” accessed March 1, 2016, http://media.elderhs.net/EHSportsArchives/StateChampionships/1956_state_baseball_champi.htm.

3 “Paul Faults Orioles With Color Movies,” The Sporting News, September 5, 1956: 9.

4 Midway through the season the Hubbers relocated across the state to Texas City.

5 “Paul Faults Orioles With Color Movies,” The Sporting News, September 5, 1956: 9.

6 “Moeller of Missions, 18, Like an Old Pro on Hill,” ibid., May 29, 1957: 36.

7 “415 Gs Gambled by Orioles on Bonus Babies Since ’54,” ibid., February 5, 1958: 6.

8 “Names to Watch? Scriveners Spill Lowdown,” ibid., April 19, 1961: 2.

9 “Haney Explodes ‘Misfit’ Handle, Hails A.L. Expansion as Success,” ibid., May 17: 8.

10 “Kid Moeller Blanks Ex-Mate Orioles—First Big-Time Win,” ibid., June 14; 14.

11 “Angels Silence Early Critics—See Rise in ’62,” ibid., October 4: 32.

Full Name

Ronald Ralph Moeller

Born

October 13, 1938 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

November 2, 2009 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.