Edgar “Blue” Washington

The mere mention of Edgar “Blue” Washington evokes thought and a curious smile, as he is undoubtedly one of the rarest of all Negro League treasures. During the early part of the twentieth century, Edgar flaunted his athleticism as a gallant young prizefighter in open-air boxing arenas in Southern California and on weekend afternoons could be found toeing the rubber for the semiprofessional Los Angeles White Sox, where his moundsmanship landed him a slot in the starting rotation of Rube Foster’s famed Chicago American Giants baseball club. After a few years in the sandlots, he held down first base for a fledgling Kansas City Monarchs franchise before hanging up his spikes to forge a career as a motion picture film actor. Edgar Washington, a brave African-American man, earning a scattered living in an unyielding world: boxer, ballplayer, actor — a true pioneer.

The mere mention of Edgar “Blue” Washington evokes thought and a curious smile, as he is undoubtedly one of the rarest of all Negro League treasures. During the early part of the twentieth century, Edgar flaunted his athleticism as a gallant young prizefighter in open-air boxing arenas in Southern California and on weekend afternoons could be found toeing the rubber for the semiprofessional Los Angeles White Sox, where his moundsmanship landed him a slot in the starting rotation of Rube Foster’s famed Chicago American Giants baseball club. After a few years in the sandlots, he held down first base for a fledgling Kansas City Monarchs franchise before hanging up his spikes to forge a career as a motion picture film actor. Edgar Washington, a brave African-American man, earning a scattered living in an unyielding world: boxer, ballplayer, actor — a true pioneer.

Washington was a ruggedly charismatic character, whether knocking heads, bruising baseballs or performing his own movie stunts as a close family friend, Woody Strode, marveled in his autobiography, Goal Dust: The Warm and Candid Memoirs of a Pioneer Black Athlete and Actor: “Athletically, Blue had the ability to do just about any damn thing he wanted. He was a hell of a baseball player, a big powerful man; he went about six-feet-five and weighed well over 200 pounds.”1 Washington’s unshakable image followed him like a star throughout his life: boisterous, entertaining and forever a rolling stone. Strode explained: “Blue was a playboy, for want of a better name. He liked the girls, bright lights, and so forth and he really put his heart and soul into it. … Blue could have been a star. At one point they gave him his own dressing room. … Blue was making seventy-five dollars a day when guys were making ten, fifteen dollars a week. He’d get four or five days in, have $300 in his pocket and nobody would see him again until the money was gone. The Washington family was constantly looking for Blue because some director was holding up a production until he could be found.”2

Edgar Hughes Washington was born on February 26, 1898, in Los Angeles, and was raised along with five siblings.3 His mother ran a nursery at the local grammar school and took additional work that included anything from janitorial work to sewing in order to raise her family.4 Edgar was a rambunctious kid with an appetite to go along with his larger-than-life stature. His family called him “Biscuits,” for he would often devour an entire pan of baked delights before his brothers and sister arrived home from school.5 The nickname that eventually stuck was “Blue,” and it came from none other than Frank Capra, one of his best pals in the ethnically diverse surroundings of Lincoln Heights, East Los Angeles, and later one of the most powerful film directors in Hollywood during the 1930s and ’40s.6

Boxer Kid Blue

Rather than follow in the footsteps of his older brothers as laborers at the local brickyard, the 14-year-old, nearly 6-foot, 170-pounder began boxing professionally as “Kid” Blue (after fudging his age). In a time when Jack Johnson reigned as the first African-American world heavyweight champion, Blue fought gamely against well-seasoned opponents 10 years his senior, enduring relentless hecklings in the largest arenas the area had to offer. He fought a four-round exhibition match against 6-foot-2-inch Harry Wills, then holder of the World Colored Heavyweight Championship. A Los Angeles Times newspaper article published on November 23, 1914, described the previous afternoon’s bout: “Gosh! Harry Wills floors Blue. … The Children’s Hospital got $323.96, Kid Blue got a sore jaw. … Wills took himself thoroughly in earnest, wading into Kid Blue in the second round of their argument and precipitating him upon his posterior organism. Four rounds with Blue, two with Jimmy Carter and four with Bob Summerville constituted a day’s work for the tall guy.”7

Washington’s professional boxing career is chronicled in Kevin R. Smith’s The Sundowners: The History of the Black Prizefighter 1870-1930, Volume II, Part One. As Kid Blue, he fought a half-dozen times without defeat in three years, debuting with an August 23, 1912, first-round knockout of Jim Newton and concluding his career with a September 21, 1915, six-round draw against Arthur Collins.8

Remaining true to Blue’s character, a retrospective article titled “Graveyards Close When He Quits” in the Times on August 19, 1920, reads: “One of Harold Lloyd’s supporting cast is an old-time colored heavyweight boxer named ‘Kid’ Blue, who never loses an opportunity of telling how ‘bad’ he used to be. ‘On the level, now,’ said Lloyd. ‘Were you a tough man in the ring — just how tough were you?’ ‘Draw yo’ own conclusions, Mistah Lloyd,’ answered the solemn veteran, ‘when Ah stopped fightin’ they closed up the graveyards.’”9 Acclaimed boxing historian Smith followed with “Edgar was well-liked in Hollywood. He had a friendly manner, was intelligent and always ready to make people laugh. In his early career he worked a great deal with Harold Lloyd, the silent film comedian who was a master of physical stunts. Lloyd was close enough with Blue that the former rented the ex-fighter one of his bungalows in Los Angeles. Lloyd found Blue to be amusing and often times retold stories to the press of Edgar’s musings.”10

To those who knew him, Blue was considered to be a “bad boy,” an attitude molded from the rough-and-tumble neighborhood in which he grew.11 Between stints in the ring, trouble reluctantly found young Washington when on December 8, 1914, a Los Angeles Times article noted that “two young colored men awaited trial on charges of auto machine thefts” and that one of these youths, Edgar Washington, would come up for trial in the juvenile court.12 The results of which are irrelevant as Washington sidestepped the chain gang, donned vertical stripes and went on to compete with the finest players on two of the greatest baseball teams in Negro League history.

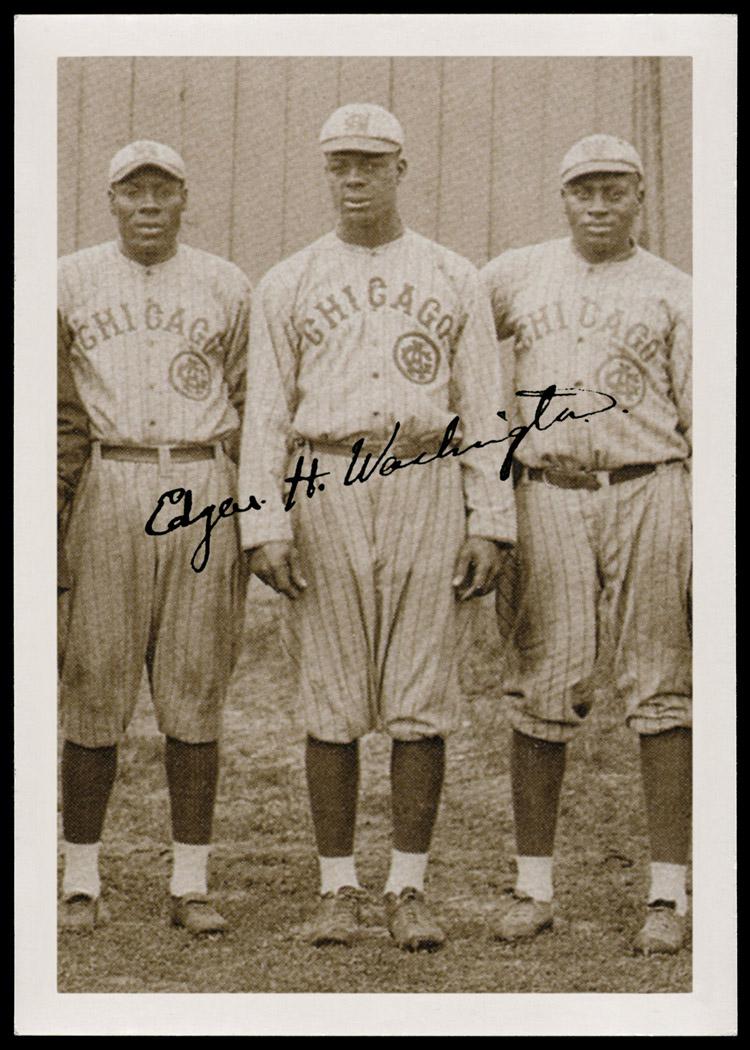

The only known photograph of Edgar Washington’s pitching days with the 1916 Chicago American Giants (left to right): Pete Hill, Harry Bauchman, Steve Dixon, Tom Johnson, Judy Gans, Bruce Petway, Rube Foster, Leroy Grant, Edgar Washington, Unknown #1 (Possibly C. Bernice Wood), John Henry “Pop” Lloyd, Unknown #2 (Possibly Clarkson Brazelton), and Frank Duncan. Note: This panoramic photo was taken by Stuart Thomson in mid-April 1916, inside Athletic Park, Vancouver, British Columbia. It was auctioned in the spring of 2012, by Robert Edward Auctions, and sold for an astounding $38,513.00. Positive player identifications by Gary Ashwill and Mark V. Perkins.

Pitcher Ed Washington

While pitching for Lonnie Goodwin’s Los Angeles White Sox, Rube Foster – the Father of Black Baseball — discovered Edgar during the Chicago American Giants’ 1916 West Coast spring-training schedule. Washington was invited to travel along and pitch for the legendary team, one comparable to the fabled New York Yankees’ Murderers’ Row, at a time when Babe Ruth was still polishing his pitching skills as a member of the Boston Red Sox. This Giants team produced three National Baseball Hall of Famers: Pete Hill, Pop Lloyd, and of course Foster.

During Washington’s brief tenure with the American Giants, he pitched in seven games, recording three victories against one loss versus white aggregations of the Pacific Coast and Northwestern Leagues.13 “Ed Washington,” as the sportswriters initially referred to him, ruled the mound with an unorthodox pitching style. Of his first appearance, a March 31, 1916, contest against the Portland Beavers in Sacramento, the Chicago Defender on April 8, reported the action:

“Inability to hit the offerings of Ed Washington, 18-year-old pitching phenom picked up in Los Angeles by ‘Rube’ Foster and the poor fielding of Shortstop Ward were two things that beat Portland again Friday, the American Giants walking off with the second game by a 5 to 2 score. With a deceiving underhanded delivery and some shoots a sight more deceiving than his delivery, Washington tolled on the mound to good effect. Inning after inning Mack [Walter “Judge” McCredie] sent his heavy hitters to the plate, only to have the majority of them return to their starting point. Portland’s two runs were not primarily the fault of the youthful black hurler. They were both made after Second Baseman Bauchman had allowed two men on bases by boots on easy chances. … Although Portland got men on in the second and third, they were unable to get around, due to the effective pitching of Washington.”14

The Portland Oregonian on April 1, 1916, carried another account of Washington’s near- shutout pitching performance headlined, “Colored Giants With Gem’m’m Known as Washington in Box Wallop Beavers”:

“The Chicago Colored Giants gave his Coast League hopes another severe lacing today — the second straight. This time the score was 5 to 2. …The colored gentleman plunked the boys for some 13 safety big swats. … Washington was having the time of his life out there in the box for the Negroes. … He allowed only five hits and would have pitched a shutout except for a couple of boots by Bauchman in the seventh inning.”15

As good fortune would have it, Washington’s string of stellar pitching performances seemed to all but guarantee him a spot on the Giants’ Opening Day roster. On April 29 the Chicago Defender printed an enthusiastic article with the lead “American Giants open to-day, big crowd see opener, eighteen-year-old Washington may pitch”:

“The Chicago American Giants left Chicago October 15, and when they return they will have been gone just six months and fifteen days. They won the Winter League pennant in California, jumped from Los Angeles to Havana, Cuba, a distance of 4,700 miles, to play in the Cuban Winter League, winning seven and losing eight games. Then they jumped to Sacramento, keeping their spring schedule intact. They have won 57 games and lost 15 up to date. When the Giants hit Chicago they will have traveled over 20,000 miles. … Rube picked up a youngster from Los Angeles named Washington and he is a comer, a cool clever pitcher with a curve ball and plenty of nerve to use it. … Mr. Foster has plenty up his sleeve. Come out and welcome the boys and see a real ball game.”16

However, unbeknownst to the local Chicagoans, Washington’s string of remarkable pitching performances had begun to unravel. In a rocky start on April 16, 1916, he hit a batter, walked four, and allowed five runs to score in one inning. Catching up with the game on the 29th, the Defender headlined its story “American Giants Win Uphill Game 10-8, Rube Sends Washington to the Showers When He Blows.”17

Back then, word traveled slowly to the Eastern periodicals, and it wasn’t until the May 6 Defender hit the streets that the tale unfolded: “Woods and Washington given walking papers, failure to keep in condition costs Los Angeles boy his place. … The boys were all well, but the two new faces we expected to see were missing. Woods had been handed his release because his arm went back on him and Washington, the kid pitcher of Los Angeles, who was the most promising in years, was found with a couple questionable characters (white, at that), and too much King Alcohol under his belt. No place on a ball team for those who want to get soused, and the little blue slip was handed Washington, to his dismay. Any manager is forced to have discipline. So be it with Foster.”18

Down the coast, the California Eagle picked up the story on April 29 and offered another twist, as sportswriter Hilbert L. Rozier questioned in his column: “We never had any reason to believe ‘Rube’ Foster doesn’t know much about ball players until he sent Washington and Woods home. Woods says that Rube told them their arms needed rest but we are inclined to believe he was a little bit out of form when he said this. When ‘Blue’ Washington was pitching at Seal Garden last Sunday he crossed Baker, his catcher up. Baker side-stepped and the ball went all the way to the grandstand before striking the ground. The grandstand is 90 feet back of the home plate. Does not look much like a sore arm, does it?”19

With a giant opportunity spoiled, Blue returned home, hooked on with his former White Sox teammates and seamlessly assumed his pitching duties. Washington also earned his keep as the team’s hard-hitting shortstop and put together a banner 1916-17 season.20 At one point during the season, the White Sox strolled along undefeated as described in a San Diego Tribune article dated October 19, 1916: “The White Sox claim to have passed through the present season without suffering the sting of defeat, and are most hopeful of burying the most bragged of San Diegans along with the rest they have laid on the wayside. … Goodwin has a staff of three pitchers and two catchers, but will likely employ his star battery Edgar Washington and Tommy Shores. Washington is said to possess a tremendous amount of steam.”21

The September 22, 1916, Chicago Defender boasted, “Far Western Champions Los Angeles White Sox; Managed by Lonnie Goodwin, recognized as the best baseball man in the west. He was one of the best pitchers in baseball, being the official scout of the American Giants. It was from his club that the American Giants were able to use Woods and Washington, two of his star pitchers, on their recent trip on the coast; both are highly spoken of by Rube Foster. In the past four years the American Giants was the only club that has bested them in a series of games. Out of thirty-six games they have played this season they have returned victorious in thirty. They will play in the Winter league this fall in California, having been voted the franchise of the American Giants, who will play the winter in Palm Beach, Florida.”22

On September 12, 1918, Washington honored his country and registered for the World War I draft, though he was not selected for service.23 Prior to enlistment, he married 16-year-old Marion Lenán, from Kingston, Jamaica, who gave birth to their son, Kenneth Stanley Washington, on August 31, 1918.24 Kenny Washington eventually became a football legend, the first African-American to play baseball at UCLA, the first Bruin player to be named an All-American and to have his number retired.25 His teammate, Jackie Robinson, described him as the greatest football player he had ever seen, adding that Kenny “had everything needed for greatness — size, speed, tremendous strength, and was probably the greatest long passer ever.”26 Kenny was the first black to reintegrate the National Football League, signing a contract to play professional football for the Los Angeles Rams in 1946. Had Kenny been allowed to come directly into the league at his prime, when he was the number-one player in the nation in 1940, he could have been one of the greatest players in NFL history.27

Indeed, the Washingtons were a family of firsts. Edgar’s younger brother Roscoe “Rocky” Washington holds the distinction of being the first black lieutenant on the Los Angeles Police Department.28 Rocky’s wife, Hazel, a socialite who became a business partner with actress Rosalind Russell, earned her star as one of Hollywood’s first black licensed hairdressers. It’s important to note that Uncle Rocky and Aunt Hazel are credited for raising the young Kenny Washington and setting the standard that carried him into the prestigious UCLA.29 Grandson Kenny Washington Jr. was a baseball star at the University of Southern California, as were great-grandsons Kraig and Kirk Washington, both of whom were drafted by the Chicago Cubs and played minor-league baseball.30

Slugger Blue Washington

While Blue eked out a living playing semipro ball, he hankered for the bright lights of Hollywood and stumbled onto the silver screen with his comedic silent film debut in Rowdy Ann (1919), with moderate success.31 By the spring of 1920, however, Washington was invited to join his former Los Angeles White Sox teammates George “Tank” Carr and John Wesley Donaldson as members of J.L. Wilkinson’s newly formed Kansas City Monarchs.32 After his debut with the club, the Kansas City Star wrote on April 19, “The batting of Edgar Washington was a feature. He got four hits out of as many trips to the plate. Two of the wallops were 3-baggers, one coming with the bases loaded and the other with two teammates on.”33 The Kansas City Sun hopped on the Blue bandwagon with a May 1 article touting, “On first base is Big Blue Washington, a new man from Los Angeles, Mendez says he has a find, a hard hitter and a player with lots of pep.”34

Washington was the starting first baseman for the Monarchs and dotted sports pages with outstanding play as noted by the Chicago Defender during a May 9, 1920, league game that spoiled the debut of the St. Louis Giants: “There were no thrill producing stunts on either side until the sixth, when with two outs, Washington, the movie star from the coast, now playing first base for the Monarchs, slammed one out in right field for two sacks; Donaldson followed with a two out station blow to left field, the movie star scoring.”35

Blue furthered his batting exploits on May 22 as a Muncie (Indiana) Morning Star article described the action: “The K.C. squad batted around and Washington had the unique distinction to make a double and triple in one inning. … Triples by Lightner, Washington and Shively went to the fence.”36 Word galloped around baseball circles, for both his baseball prowess and big-screen success as a May 22 spread offered by the Chicago Defender noted: “Blue Washington, who has been featured recently in the motion picture, ‘Haunted Spooks,’ is playing first base for the K.C.’s and he is not only a grand fielder, but he is one of the heaviest batters in the game today.”37

After a few months of arduous barnstorming, Washington made history when he played in the Monarchs’ very first Negro National League game at Association Park in Kansas City on May 29, 1920.38 He played his final game on June 15, appearing as a pitcher, and was unceremoniously knocked out of the box in the first inning after allowing five runs.39 In 24 official league games, the 6-foot-2 slugger batted .275 with 16 RBIs for a heralded Monarchs team that boasted future Hall of Famers José Méndez and Bullet Rogan.40 Why did his promising baseball career end so abruptly? Perhaps one could venture a guess that all the ballyhooed press had gone to his head. One thing for sure, and not so surprisingly for athletes from any era, he would again rejoin the Los Angeles White Sox for few games in December 1920 and was believed to have played a number of California Winter League independent play games with Alexander’s Giants.41

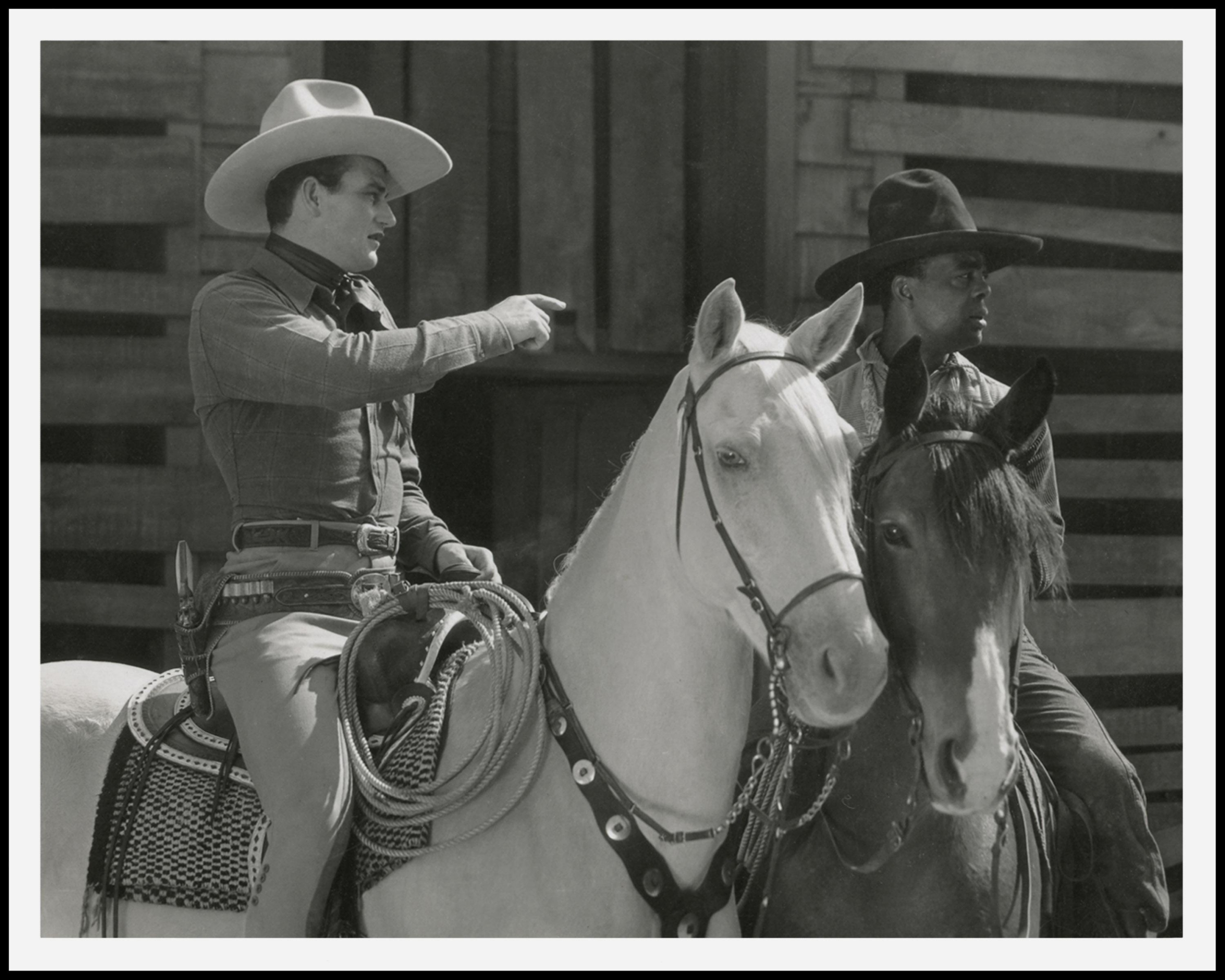

Haunted Gold (1932) unpublished publicity still – HG 31 #3 – featuring John Wayne (as John Mason) and Blue Washington (as Clarence Washington Brown). Courtesy of Kysa Lenán Washington.

Actor Blue Washington

While using the screen name “Edgar Blue,” Washington became one the earliest African-American actors in the silent-film era, having been selected for some of the finest comedic and dramatic roles of his time. As Blue Washington, he holds the distinction of being one of only two black cowboy sidekicks ever featured in B-westerns, appearing opposite John Wayne in Haunted Gold (1932).42 Blue acted in some of Hollywood’s classics: The Birth of a Nation (1915),43 the first ever epic and highest-grossing silent film of its era; Beggars of Life (1928); the original King Kong (1933); and Gone With the Wind (1939).44 He acted alongside Richard Arlen, Lex Barker, Charlie Bowers, Warner Baxter, Wallace Beery, Louise Brooks, Bing Crosby, Mildred Davis, Bob Hope, Dorothy Lamour, Vivien Leigh, Harold Lloyd, Ken Maynard, and Fay Tincher.

On July 24, 1927, Los Angeles Times film columnist Norbert Lusk described Washington’s on-screen performance: “‘Blood Ship’ Hailed as Best Picture of Week in Gotham. … Blue Washington, a colored actor, has been singled out for honorable mention on the score of vivid and spontaneous acting.”45 In a film review published in the Afro-American on May 4, 1929, Blue’s acting abilities were given quite a boost with his portrayal of “Big Mose” in Paramount Pictures’ first sound film with dialogue: “In ‘Beggars of Life’ Edgar Blue Washington, race star, was signed by Paramount for what is regarded as the most important Negro screen role of the year.”46

Author Thomas Cripps noted Washington’s on-screen abilities in Slow Fade to Black: The Negro in American Film 1900-1942: “After years of conversation movies began to catch up with social change by creating some Negro roles that were far more assimilationist than would have been possible in the actual life of the twenties. In one of his first pictures, Beggars of Life, William Wellman adapted Jim Tully’s picaresque tale of hobo life to the screen. Louise Brooks played a young girl who accidentally kills her brutal foster father. Richard Arlen’s hobo helps her escape to the dangers of hobo jungles and the brutality of ‘Oklahoma Red’ (Wallace Beery). Along the way Edgar ‘Blue’ Washington, a sometime Los Angeles policeman, appears as Mose, a black wanderer who joins the pair in their struggle. Throughout their brief alliance he is their equal and their champion. When Red and Arkansas Snake fight over the girl, it is Mose who knocks a knife from the Snake’s hand. He is the train-wise hobo who can elude the railroad police and miraculously forage for food. … In their final moments together Mose and Red dress a corpse in the girl’s clothes and set it afire in a boxcar in order to let the girl escape to Canada. Mose covers the escape by elaborately ‘tomming’ the police. Even so, despite Washington’s central role, Variety took no notice of his presence.”47

Cripps followed with a similar critique in a subsequent film: “Rare was a role like Blue Washington’s tribal chief who kills a Boer in Passion Song (1928). Generally blacks remained exotic atmosphere for white plots even though the bulk of racial ambiguity peered through.”48 Although Washington’s landmark role in Haunted Gold stands as his most visible, he is thought to have appeared in close to 100 films. Vintage Hollywood movie posters, lobby cards and glossies featuring Washington’s image have fetched a premium in the collectible markets.

The spotlight on Washington’s acting career dimmed with stereotypical roles in movies such as Law of the Jungle (1942), Tales of Manhattan (1942), and Tarzan’s Magic Fountain (1949), after which he faded into obscurity with brief, uncredited screen performances in Stars and Stripes Forever (1952), The Wings of Eagles (1957),49 and The Horse Soldiers (1959).50 Author and Negro Leagues baseball researcher Gary Ashwill noted: “According to some accounts Blue had to endure hazing and practical jokes from white co-workers, and often appeared in the credits as ‘handyman’ instead of actor.”51

The recollections are varied, but none encapsulates his personality more than in Woody Strode’s memoir: “Blue could have been a star. At one point they gave him his own dressing room. They made a picture in which he was the star but they never did release it because towards the end Blue screwed up and disappeared. It was called Ormsby the Faithful Servant. Blue played Ormsby. They shot the last scenes out on the Santa Cruz Island and Blue never showed up. They spent a lot of money on that picture; Blue alone was getting $750 a week. I’ve never forgotten that; that was a fortune. And it was that production that pretty much ended his career in the movies.”52

As far as the historical marker left from his extensive acting career goes, the closing sentiment should suffice; Edgar “Blue” Washington, a film pioneer and for such trailblazing efforts, for which a host of African-American successors are unwittingly grateful.

Edgar Hughes “Blue” Washington, died on September 15, 1970, at Mira Loma Hospital in Lancaster, California. He was laid to rest on September 18 at Evergreen Memorial Park, the oldest existing cemetery in Los Angeles.53 A single burial in a double-grave plot became his eternal resting place. Beside him lies son Kenny, who died less than a year later, on June 24, 1971.54

Haunted Spooks (1920) reissue lobby card – A ghost in disguise – featuring Harold Lloyd (as the Boy) tangled in bed sheet and Edgar Blue (as the Butler) gazing from the foot of staircase.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Gary Ashwill and Peter Gorton, who both contributed mightily. John Klima, who urged me as “Blue’s champion” to fight the good fight, and Jeremy Krock, with the Negro Leagues Grave Marker Project, honoring those forgotten baseball stars, like Blue Washington, with proper visual remembrances.

Notes

1 Woody Strode and Sam Young, Goal Dust: The Warm and Candid Memoirs of a Pioneer Black Athlete and Actor (Aurora, Ontario: Madison Books, 1984), 53.

2 Ibid.

3 Author Mark V. Perkins has chosen February 26 as Edgar Washington’s birthday, although February 6 is listed in the Social Security index and February 12 is listed on his death certificate (and thus canonized as the official date), since the February 26 date is written on the earliest document known to be signed by Washington himself, his World War I draft registration card.

4 Donald Bogle, The Story of Black Hollywood: Bright Boulevards, Bold Dreams (New York: Ballantine Books, 2005), 142.

5 Woody Strode and Sam Young, 53.

6 Joseph McBride, Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success (Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 1992), 35.

7 “Gosh! Harry Wills Floors Blue,” Los Angeles Times, November 23, 1914.

8 Kevin R. Smith, The Sundowners: The History of the Black Prizefighter 1870-1930, Volume II Part One (New York: CCK Publications, 2006), 94.

9 “Graveyards Close When He Quits,” Los Angeles Times, August 19, 1920.

10 Kevin R. Smith, 93.

11 Donald Bogle, 142.

12 “Comb City for Auto Thieves,” Los Angeles Times, December 8, 1914.

13 Email correspondence with Gary Ashwill, 2012.

14 “Beaver Veteran Hurler Looks Same to Giants,” Chicago Defender, April 8, 1916.

15 Roscoe Fawcett, “Hig And Sothoron Lose To Tune of 5-2,” Portland Oregonian, April 1, 1916.

16 “American Giants Open To-Day,” Chicago Defender, April 29, 1916.

17 “American Giants Win Uphill Game 10-8,” Chicago Defender, April 29, 1916.

18 Home Run, “E. Pluvius Is King,” Chicago Defender, May 6, 1916.

19 Hilbert L. Rozier, “Our Athletics,” California Eagle, April 29, 1916.

20 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2002), 60. See also email correspondence with Peter Gorton, 2012, The John Wesley Donaldson Network, “Teams,” johndonaldson.bravehost.com/t.html and “Calendars 1917-1919” johndonaldson.bravehost.com/ds.html, accessed January 1, 2013.

21 “White Sox Proud Record,” San Diego Tribune, October 19, 1916.

22 “Brilliant Pitchers’ Battle to Sox, 4-3,” Chicago Defender, September 22, 1916.

23 National Archives, Atlanta. William F. McNeil, 61. See also Agate Type, “George Carr, Movie Actor, August 12, 2007.” agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/george-carr/, accessed January 1, 2013.

24 Woody Strode and Sam Young, 52. Personal and telephone interviews with Kysa Lenán Washington, 2012.

25 Woody Strode and Sam Young, 59; Donald Bogle, 143; Baseball Reference, BR Bullpen, “Kenny Washington” baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Kenny_Washington, accessed January 1, 2013.

26 Thomas G. Smith, “Outside the Pale: The Exclusion of Blacks From the National Football League, 1934-1936,” Journal of Sports History, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Winter 1988): 266, aafla.org/SportsLibrary/JSH/JSH1988/JSH1503/jsh1503d.pdf, accessed January 1, 2013.

27 “Lost History: The NFL’s Jackie Robinson,” Sports Illustrated, October 12, 2009. Kenny Washington Stadium Foundation, “Kenny,” kwsfoundation.org/kenny/, accessed January 1, 2013. Personal, telephone, email correspondence with Stephen Lampson, 2012. Additionally, Kenny Washington appeared in a number of films, from While Thousands Cheer (1940), an all-black-cast sports drama, to The Jackie Robinson Story (1950), in which he is credited as the “Tigers Manager.”

28 US Census Bureau, 1930 US Census; Agate Type, “Forgotten Negro Leaguers, Ajay Deforest Johnson, Part II,” July 4, 2008, posted by Gary Ashwill, agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/forgotten_negro_leaguers/, accessed January 1, 2013; Association Of Black Law Enforcement Executives, A History Of Honorable Service Since 1886, “Lieutenant Roscoe “Rocky” Washington,” ablelapd.com/article__rockywashington_pg2.html, accessed January 1, 2013.

29 Donald Bogle, 141.

30 Black College Nines, Black Pioneers of College Baseball, “Kenny Washington (UCLA),” February 16, 2010, blackcollegenines.com/?p=790, accessed January 10, 2013. Personal interview, telephone interview, email correspondence with Kirk Washington, 2012, and personal interview with Kraig Washington, 2012.

31 Internet Movie Database IMDb, “Blue Washington,” imdb.com/name/nm0913405/, accessed January 1, 2013.

32 Email correspondence with Peter Gorton, 2012. The John Wesley Donaldson Network, “Teams” johndonaldson.bravehost.com/t.html, and The John Wesley Donaldson Network, “Calendars 1917-1919” and “Calendars 1920-1922,” johndonaldson.bravehost.com/ds.html, accessed January 1, 2013. See also Agate Type, “George Carr, Movie Actor,” August 12, 2007. Posted by Gary Ashwill, agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/george-carr/, accessed January 1, 2013. “The Monarchs Play Today,” Kansas City Star, April 18, 1920.

33 “An Easy Win for the Monarchs,” Kansas City Times, April 19, 1920.

34 “Sports,” Kansas City Sun, May 1, 1920.

35 Dave Wyatt, “K.C. Monarchs Trim the St. Louis Giants,” Chicago Defender, May 15, 1920.

36 “Slugfest Held at Walnut Park,” Muncie (Indiana) Morning Star, May 23, 1920.

37 “K.C. Monarchs Here Sunday,” Chicago Defender, May 22, 1920.

38 “The Monarchs Play Today,” Kansas City Star, May 29, 1920.

39 Email correspondence with Peter Gorton, 2012. See also The John Wesley Donaldson Network, “Teams” and “Calendars 1920-1922.” “A Late Rally Beat Monarchs,” Kansas City Times, June 16, 1920.

40 Seamheads, “Edgar Washington,” seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?ID=811, accessed January 1, 2013.

41 William F. McNeil, 74, 78.

42 Boyd Magers, “The Westerns Of John Wayne,” westernclippings.com/westernsof/johnwayne_westernsof.shtml, accessed January 1, 2013.

43 Joseph McBride, 63. Internet Movie Database IMDb, “Blue Washington,” imdb.com/name/nm0913405/, accessed January 1, 2013.

44 American Film Institute Catalogue of Feature Films AFI, “Blue Washington,” afi.com/members/catalog/SearchResult.aspx?s=&retailCheck=&Type=PN&CatID=DATABIN_CAST&ID.=22331&AN_ID=16710&searchedFor=Blue_Washington, accessed January 1, 2013.

45 Norbert Lusk, “Columbia Produces Success,” Los Angeles Times, July 24, 1927.

46 “Wings, Beggars of Life, Sawdust Paradise,” The Afro-American, May 4, 1929.

47 Thomas Cripps, Slow Fade to Black: The Negro in American Film 1900-1942 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), 154, 165.

48 Ibid.

49 Internet Movie Database IMDb, “Blue Washington,” imdb.com/name/nm0913405/, accessed January 1, 2013.

50 Author Mark V. Perkins’ positive identification of Edgar “Blue” Washington appearing as “Himself-Blue,” servant at Newton Station Hotel, a previously undocumented credit in John Ford’s thunderous motion-picture spectacle The Horse Soldiers (1959), starring John Wayne and William Holden.

51 Email correspondence with Gary Ashwill, 2012.

52 Woody Strode and Sam Young, 53.

53 Personal and telephone interviews with Marvel Washington, 2012.

54 Evergreen Memorial Park, Los Angeles.

Full Name

Edgar Hughes Washington

Born

February 26, 1898 at Los Angeles, CA (US)

Died

September 15, 1970 at Los Angeles, CA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.