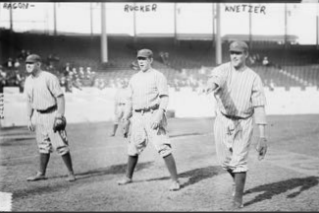

Elmer Knetzer

In the final month of the 1909 National League season, Elmer Knetzer of the Brooklyn Superbas took the mound for his first major-league game. His opponents were John McGraw’s mighty New York Giants. Before 10,000 Giants rooters at the Polo Grounds, the rookie right-hander could not have been matched with a more formidable opponent than Christy Mathewson, the best pitcher in the game.

In the final month of the 1909 National League season, Elmer Knetzer of the Brooklyn Superbas took the mound for his first major-league game. His opponents were John McGraw’s mighty New York Giants. Before 10,000 Giants rooters at the Polo Grounds, the rookie right-hander could not have been matched with a more formidable opponent than Christy Mathewson, the best pitcher in the game.

The shaky rookie walked the first batter, Larry Doyle, who stole second base, then third. Knetzer was able to escape the first inning, but he walked the first two batters in the second. Later that inning, the Giants’ Chief Meyers slugged a home run off the parapet in left-center field, putting the newcomer’s team down, 3-0. Knetzer settled down after that and posted zeros on the scoreboard for the remainder of the contest. But it was Mathewson who ruled the day with a three-hit shutout.

“I took a razzing from John McGraw when I made my debut against the Giants,” recalled Knetzer. “McGraw started after me from the coaching line with the first pitch and never ceased his verbal fire. But it didn’t bother me.”1

Two and a half weeks later, in Cincinnati, Knetzer won his first major-league game with an 11-inning, 4-1 victory. Despite his losing three of four decisions that September, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle predicted, “Knetzer has all the earmarks of a good pitcher.”2

Knetzer’s success was due to an “extremely good fast ball,” and “the best balk motion in the game,” with an occasional “wet one” thrown in.3

Elmer Ellsworth Knetzer was born on July 22, 1885, in Carrick, Pennsylvania (the community eventually was annexed by Pittsburgh.) His grandparents had left Germany for a life in the coal fields of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. Elmer’s father, Christian Knetzer, and his older brother, John, labored in the coal mines, and when Elmer completed sixth grade, he too would be expected to do the same.

Elmer’s passion was playing baseball with independent sandlot teams, including the Carrick Volunteers, sponsored by the local fire department. Joe Kelly of the Boston National League club heard about this sensational pitcher and traveled to Carrick, where he liked what he saw in Elmer. However, Elmer’s father forbade his son to sign a professional baseball contract.4

Knetzer continued to play the game he loved, as a shortstop and pitcher. In 1909 Mal Eason, manager of the Lawrence (Massachusetts) team in the New England League, signed Elmer to pitch for his team in the New England League. The 24-year-old rookie wasn’t with Lawrence very long.

Knetzer, soon to be nicknamed “Carrick Baron” by Abe Yager of the Brooklyn Eagle, would pitch for the Superbas over the next three years. In his first full major-league season, Knetzer won seven of 12 decisions, three of them shutouts. His club had its usual second-division finish, even changing the nickname from Superbas to Trolley Dodgers after the 1910 season. The change did not affect the club’s losing ways.

John B. Foster, baseball writer and sports editor for The Spalding Guide, praised Knetzer in the final weeks of the 1911 season: “If he can only start next Spring with some of the stuff that he has this Fall, he will be one of the best pitchers in the National League. … His speed is admirable, and he can whiff a drop around the corners of the plate that is only exceeded in speed by the general whiffing on the part of the batters who try to hit the ball.”5

Knetzer’s performance in 1912 was unexpected, as he declined in almost every pitching category. When it came time for his 1913 contract renewal, club owner Charles Ebbets reduced his salary. Knetzer refused the club’s offer and swore he would stay at home in Carrick until President Ebbets agreed to his terms. He held out well into the season.

By summer it was obvious that neither party was going to give in. Manager Deacon Phillippe of the Pittsburgh club in the fledgling Federal League, sought to acquire Knetzer. The lure of playing near his home might have convinced Elmer, though he was joining a low-level minor league. In June 1913 Knetzer became the first player bound to the major leagues’ reserve clause to sign a contract with the Federal League. In its second season, the league declared itself a major league and commenced recruiting as many major-league players as it could.

On April 14, 1914, Knetzer was the Pittsburgh Rebels’ Opening Day pitcher against Tom Seaton of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops. The game was scoreless until the 10th inning, when Pittsburgh’s shortstop Tex McDonald couldn’t handle a bad hop with a runner on third base. Knetzer was on the losing end of a 1-0 score.

For Knetzer, the Rebels weren’t any better than the Dodgers. After winning only three of their first 11 games, manager Doc Gessler was replaced by outfielder Rebel Oakes. The Rebels finished the season in seventh place.

Knetzer was stellar despite the team’s losing ways, winning 20 of the Rebels’ 64 victories. (He lost 12 games.) Perhaps his best pitching performance came on October 9. Both Knetzer and Buffalo’s Russ Ford put zeros on the scoreboard for 15 innings. Buffalo scored the only run of the contest in the 16th inning.

Afterward, Knetzer received a check for $1,000 from the Pittsburgh club president, Edward W. Gwinner, for being the team’s most consistent pitcher. Knetzer also signed a two-year contract with a pay increase to $5,100 per season.6

Knetzer had a fever and missed pitching the Opening Day game in 1915. As his condition regressed, his affliction was diagnosed as malaria. The disease sapped his strength, allowing Knetzer to be used only in relief in the first part of the season.

Knetzer’s first start of the season came in the first game of a doubleheader at Pittsburgh’s Exposition Park on May 25. He allowed 12 hits and four walks in a loss to the Tip-Tops. Five days later, in St. Louis, he was his old self with a “baffling selection of twists and shoots.”7 In his 4-0 victory, Knetzer allowed the Terriers only four singles, but was rusty in issuing five walks.

With the addition of several new players, Pittsburgh stayed in the pennant hunt, and going into the final weekend the Rebels were in first place by the smallest of margins; they had held a half-game lead for several days. Because of rainouts, Pittsburgh was to play doubleheaders at Chicago’s Weeghman Park on consecutive days. On Saturday, Pittsburgh lost both games, giving the Whales a half-game lead over the Rebels going into the final day of the season.

Knetzer was scheduled to pitch the second game on Sunday, despite throwing two-plus innings the previous day. However, Rebels manager Oakes summoned him in the first game with the score knotted at 4-4 after nine innings. There was no scoring in the 10th, but an inning later Knetzer led off with a single, then was sacrificed to second base. Al Wickland’s wicked smash caromed off the shin of Whales shortstop Mickey Doolin allowing Knetzer to score the lead run. Knetzer retired the side in the bottom of the inning to secure a 5-4 victory.

Although he would pitch for the third time in two days, Knetzer took the mound for the second game, which would decide the championship. For the first five innings, Elmer and the Whales’ Bill Bailey put zeros on the scoreboard. In the sixth, Chicago shortstop Doolin led off with a single. A sacrifice and an infield out landed Doolin on third base. If Knetzer could retire the next batter, the game was likely to end in a tie because of the setting sun. If so, the Rebels would win the championship.

Knetzer ran the count on Chicago’s Max Flack to 2-and-2 before Flack connected with his next pitch. Because of the descending darkness, center fielder Oakes misplayed the ball and deflected it into the standing-room crowd behind a rope line. Knetzer always maintained that in normal conditions “it would have been duck soup for (Oakes). Yep, if Reb had just held that ball we’d won.”8

Chicago scored three runs in that fateful inning. After the Rebels were retired in the top of the seventh, the game was called. Chicago became the 1915 Federal League champion.

On November 9, 1915, Knetzer married 24-year-old Theresa Lehrman in Pittsburgh’s St. Michael’s Church. Two days before Christmas, news broke that the Federal League was defunct, and its players were to be sold to the highest bidders.

In February 1916 the Boston Braves purchased the contracts of Knetzer and two other former Rebels. Knetzer pitched in only two games before the Braves released him on waivers. He was claimed by the Cincinnati Reds with a two-week option. Knetzer’s first appearance on the mound for the Reds was so-so, then he secured a spot with the team on May 16 when he allowed no runs in a relief stint of seven innings.

Knetzer’s most notable game in 1916 was a match with his former team, the Dodgers, on September 18. He and Brooklyn’s Rube Marquard pitched brilliantly, the score knotted at 1-1 until Cincinnati scored the go-ahead run in the 10th inning. In the face of an impending storm, Knetzer “put up some extra steam” and retired the side in order in the bottom of the inning.9

During spring training at Shreveport, Louisiana, in 1917, Knetzer complained that his right shoulder “went bad” from tonsillitis. He could not match the success of previous seasons. He pitched in only 11 games, all in relief.

When Knetzer was released to Columbus of the American Association, he refused to report. However, he decided that a good salary with a Double-A league was better than returning to the mines. The 22 games he pitched in Columbus turned out to be the 32-year-old Knetzer’s last in Organized Baseball.

When the government issued a work-or-fight order in 1918, Knetzer went to work as an electrician at the Allegheny Steel plant at Tarentum, Pennsylvania. He pitched for the plant team until a workers’ strike in the summer of 1919. Knetzer continued to play baseball for various city clubs and sandlot teams until he “retired” at the age of 55.

“I always kept in good shape, never smoking or drinking in my playing career although I was a heavy tobacco chewer,” he said in 1943.10

After baseball, Knetzer was a doorman and watchman for the Joseph Horne department store in Pittsburgh, retiring in 1954 after 16 years. He celebrated his 72nd birthday at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field by pitching one inning of an exhibition game between ex-major leaguers and former sandlotters.

Knetzer resided in the Pittsburgh area until he died on October 3, 1975. He is buried in St. Wendelin Church Cemetery in Pittsburgh.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, and the Pittsburgh Daily Post and Pittsburgh Gazette-Times.

Notes

1 Volney Walsh, “Pitching Against Christy Mathewson Gave Elmer Knetzer Thrill,” Pittsburgh Press, January 9, 1933: 23.

2 “Knetzer Pitches a Great Game,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 29, 1919: 22.

3 “Reds Hitting Ball and Sure to Climb,” The Sporting News, July 5, 1917: 3.

4 Paul A.R. Kurtz, “47-Year-Old Elmer Knetzer, ‘Carrick Baron’…,” Pittsburgh Press, March 27, 1932: 20.

5 John B. Foster, “Brooklyn Budget,” Sporting Life, September 16, 1911: 6.

6 “Pittsburgh Sensation,” Sporting Life, September 16, 1911: 6.

7 “Cincinnati Beats Pittsburgh, 4 to 0,” Pittsburgh Gazette-Times, May 31, 1915: 14.

8 “Pennant Tease,” Pittsburgh Press, August 19, 1958: 21.

9 “Double-Header Briefs,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 19, 1916: 6.

10 “Knetzer Tells of Thrills,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 12, 1943: 24.

Full Name

Elmer Ellsworth Knetzer

Born

July 22, 1885 at Carrick, PA (USA)

Died

October 3, 1975 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.