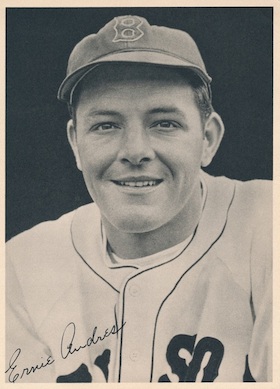

Ernie Andres

If the NBA was as big in the 1940s as it is today, Ernie Andres might have been a star basketball player. He was a guard for Indianapolis in the National Basketball League, a forerunner of the NBA, and in 1974 was inducted into the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame.1

If the NBA was as big in the 1940s as it is today, Ernie Andres might have been a star basketball player. He was a guard for Indianapolis in the National Basketball League, a forerunner of the NBA, and in 1974 was inducted into the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame.1

And in 1942, he played in an All-Star Game against the American League.

In 1946, he was a third baseman on the pennant-winning Boston Red Sox team.

It all sounds very impressive and, to be fair, he accomplished far more in professional sports than 99% of those who read this biography will have ever done. But if you look up his record, you find that sometimes it was a matter of being in the right place at the right time. Or, perhaps, the wrong place for a guy seeking a pro career.

Ernest Henry Andres Jr., was born in Jeffersonville, Indiana, on January 11, 1918, the first-born child of Minnie and Ernest. “I’m a junior,” he said in a 2001 interview. “They called me ‘Junie’ even when I was playing in Louisville.”2 Both parents were Hoosiers by birth, but Ernest’s father had come to America from the German part of Switzerland. Minnie’s parents were both native Kentuckians. His father, a bookkeeper in a state bank at the time, advanced over the years at the bank, becoming an assistant cashier by the time of the 1930 census and cashier by 1940. Junie’s younger siblings were Norma and Anna.

Ernie went to McCullough’s School, then graduated from Jeffersonville High School in 1935 and went to college at Indiana University, from which he graduated in 1939. He earned a bachelor’s and later a master’s degree in Physical Education.

He was something of a star in college, perhaps no more so than in the December 23, 1937, basketball game at the University of Nebraska. The lead had been deadlocked 11 times during the game, six times in the last period. With the score tied, 42-42, and four seconds to play, Andres was fouled and sank the game-winning free throw.3 In the March 5, 1938, games against Illinois, he set a single-game conference record, scoring 30 points. Indiana won, 45-35. He was named to the All-Big Ten first team in 1938 and 1939. In 1939 he was captain of both the basketball and baseball teams, and twice won the Balfour Award as the college’s top athlete.

Local sporting goods dealer Stan Feezle and I.U. coach Pooch Harrell recommended Andres to Louisville Colonels acting manager Bill Burwell and he was given a 10-day tryout. Burwell “put his OK on me and the club signed me at the end of 7 days.”4

Signed by the Boston Red Sox on June 1, Andres began professional play as soon as he completed college, appearing in 78 games for manager Donie Bush and the Double-A American Association Louisville Colonels in 1939 and batting .298 with four home runs. In his last at-bat in college, he’d hit a home run, and in his first at-bat for the Colonels he also hit a home run.5 There was an “Andres Night” during the season, and Louisville was trailing Kansas City by four runs in the bottom of the eighth. Andres hit a grand slam to tie the game.6 The Colonels won it in the 11th.

That winter, Andres played professional basketball for Indianapolis, and again made the occasional headline. On December 31, his last-minute field goal beat Hammond in an NBL game, earning a headline “Andres’ Shot Wins.”7

Bill Burwell replaced Bush as Louisville manager during 1939 and remained for all of 1940 and 1941. Andres completed both of the latter two seasons, playing in 111 games in 1940 and in all 154 games in 1941. His batting averages were .276 and .289, with him showing a power burst in the latter season – 15 home runs and an even 100 runs batted in. Andres was appreciative of the way Burwell helped him develop, even perhaps at the expense of simply trying to win games. “Bill Burwell was a great guy. He gave you a chance to play. He took out the only .300 hitter in the lineup he had just to give me a chance to play – me being a local boy. I lived just across the river.” The Colonels finished fourth in 1939 and 1940, and second in 1941.

It was clear that war was on the horizon and the armed forces were increasing their numbers. He drew a high draft number (“When they shook that bowl up in Washington, they left my number on top”), and was expected to be taken in the draft during the summer of 1941. He enlisted in the Navy that June, before he got the call, and as it happens was not called until after the baseball season, in September. Before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Andres was already stationed at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station. He played basketball there, and was on the first Great Lakes baseball team under Mickey Cochrane, a team featuring several former major-league ball players.

The Great Lakes Bluejackets played against a number of college and pro teams. His 3-for-5 day against his former teammates at Louisville on May 29 helped the Bluejackets win, 10-4. His home run beat Ohio State on June 13.

On the day after the major-league All-Star Game, there was another All-Star Game held — with a team of Army-Navy All-Stars playing against the winner of the All-Star Game. The American League beat the National League, 3-1, on July 6 at the Polo Grounds. So it was the A.L. team that played again the following day, July 7, at Municipal Stadium in Cleveland against the Service All-Star team. Pitching for the Service All-Stars was Chief Bos’n’s Mate Bob Feller of the U. S. Navy. Jim Bagby and Tex Hughson pitched for the A.L. team. The American Leaguers won, 5-0. The Boston Traveler observed, “The only batting of any moment — the service men made only six hits in all — was done by Ernie Andres, who was the property of the Red Sox down at Louisville before going into the Navy…he fielded his position slickly and was the only service man to make two hits.”8 He hit .360 for the Great Lakes team. Mickey Cochrane later said Andres was his “rookie of the year.”9

Andres received his commission as an ensign on October 3. Of his 52 months in the Navy, Andres said, “I was pretty lucky. I spent most of my time in the country, but I did spend a year on a sub chaser. In the Pacific. Late ’43, ’44.” He may have spent a little longer in danger’s way than he recalled in the 2001 interview. An April 8 story reported him as already “aboard a submarine chaser.”10 Much of his service was off the coast of Alaska; he was then transferred to Miami “training for the sub chaser command.”11 He wound up spending 25 months in Miami teaching sports to sailors there.

Andres had married Doris Mann of Delta, Ohio, on September 26, 1942. Their first child, Carol Jean, was born in Miami.

After he was mustered out of the service as Lt. (J.G.) E. Andres on October 5, civilian Andres was quickly signed again by Indianapolis to play pro basketball.12 And in December, the Red Sox acquired him from their farm club in Louisville. If nothing else, it was hoped he would “put a stinger under [Jim] Tabor, and do the Red Sox…a tremendous amount of good.”13 In other words, give Tabor some real competition for the third-base job, Tabor being a player seen to need extra motivation to get the most out of his exceptional natural abilities. In January 1946, the Sox sold Tabor on waivers to the Phillies.

Ty LaForest and Eddie Pellagrini were other possibilities to take Tabor’s place at third. In the end, it was Rip Russell and Mike “Pinky” Higgins who filled the slot. During the springtime, though, the job was largely Andres’s to lose. Joe Cronin had been impressed with seeing him at Great Lakes, and a Boston Herald story in early March presented favorable comments from a number of other Red Sox players.14 Cronin strongly requested that he give up playing basketball at the professional level.

Pellagrini put up some strong competition for the position; Andres struggled with his batting. It was Andres who got the 11th-hour nod, starting at third base on April 16 Opening Day in Washington. “The two new Red Sox, Rudy York at first, and Ernie Andres at third, more than filled the bill,” wrote Burt Whitman in the Boston Herald.15 Batting seventh, Andres was 1-for-4 with a double past third base in his first time at bat, and fielded and threw well, particularly on a roller that he scooped up and threw to first to close out the Senators’ sixth.

Andres started the first eight games of the season for the Red Sox but on April 23 he pulled a leg muscle running out a hit in the second inning. He didn’t return to action until May 3, and didn’t start until May 11.

His batting average had dropped to .103 after the May 11 start, his only hits being that opening day double, a single the next day, and another two-base hit on April 21. The April 21 game, a 10-inning 12-11 win over the Athletics at Fenway Park, saw him get his only RBI, on a sacrifice fly in the bottom of the sixth.

He got one more hit, a single on May 12. He was .098 after the May 16 game, the 15th in which he’d appeared. The Red Sox were 23-6 and five games ahead of the second-place Yankees in the standings at the time. It was Andres’s last game in the big leagues. He had handled 33 chances without an error.

On May 11, Joe Cronin seems to have already pretty much given up, talking about the third-base situation: “I tried Ernie Andres and Eddie Pellagrini there but neither of them worked out. Pellagrini didn’t hit his hat size and Andres didn’t look so well with the stick, either. Then Ernie hurt his leg on top of that. I’ve got Leon Culberson playing third now.”16 Glenn “Rip” Russell became the replacement at third base. On May 19, the Red Sox purchased Pinky Higgins from the Tigers. On the 29th, they optioned Andres to the Buffalo Bisons (International League.)

It seemed a logical move, even at the time, but years later Andres expressed some sense of surprise as to where he was sent. “They optioned me to Buffalo. I never could understand that. Buffalo was a Detroit farm. Why they sent me there…? I was there for about 10 days, and I finally told Bucky Harris — he was the general manager of Buffalo — and I told him to call Boston and tell them to send me some place I could play. They already had a young kid playing third base and what they’d want with me at 26 or 27, I didn’t know. They’d optioned me. They sent me out. To Detroit! Finally, after two or three days, they called back and they told me to report to Minneapolis. So I went to Minneapolis for the rest of ’46.”

He had only gotten into one game for Buffalo and was 1-for-3. And, at least with the passage of time, he really did know why he’d been let go by Boston: “I was up for a cup of coffee. I was getting old. I opened the season there. I stayed for 15 games. I was there about three weeks, maybe a month, but I wasn’t hitting very much and third basemen don’t stay there very long if they don’t hit some.”

For the 1946 Minneapolis Millers, a New York Giants affiliate, Andres played in 90 games, hit .287 with four homers, and drove in 59 runs.

On September 18, Frank Kautsky of the Indianapolis basketball club announced that he had rehired Andres for 1946-47, this time as player-coach. He was reportedly making $15,000 a year. “I was a better basketball player than I was a baseball player,” Andres said in 2001. “I was an All-American basketball player. People asked me which I liked better and I told them, ‘Well, baseball in the summer and basketball in the winter.’ I made more money playing basketball than I did playing baseball. It wasn’t very much back at that time.”17

Still on a Louisville Colonels contract, Andres let them know his basketball commitments would make him report late to spring training. This perhaps didn’t sit well. It’s also possible that Joe Cronin didn’t appreciate Andres’s remark regarding his seeking a job with the Red Sox in 1947: “I wrote him [Cronin] and didn’t get a postcard in reply.”18 A few days later, Louisville sold his contract to the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association, a Pittsburgh Pirates affiliate in 1947. Just over two weeks later, he was fired as coach by the basketball team but would stay with the team, the announcement said, “as long as he proves valuable.”19

He played in 150 games for the Indianapolis Indians in 1947, batting .266 with 85 RBIs. They were his last games in baseball. On April 2, 1948, he was named head baseball coach for Indiana University. He also worked as assistant basketball coach.

After 25 years as coach, Andres resigned in 1963 to become field secretary for the Indiana University Alumni Office. He worked for the alumni office for 10 years before retiring. Andres lived for a long time after retirement, dying at 90 in Bradenton, Florida, on September 19, 2008. He is buried in his home town of Jeffersonville.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Andres’ player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee.

Notes

1 For a history of the National Basketball League, see Murry R. Nelson, The National Basketball League: A History, 1935-1949 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009). The NBL and the Basketball Association of America merged to form the NBA. For Andres in the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame, see: http://www.hoopshall.com/index.php?xsearch%5B0%5D=Ernie+Andres&xsearch_id=HallofFame_Last_Name&src=directory&srctype=HallofFame_lister&view=HallofFame&submenu=hall_of_fame_dir&Go.x=15&Go.y=12

2 Bill Nowlin interview with Ernie Andres on May 18, 2001. All quotations attributed to Andres come from this interview unless otherwise noted.

3 Associated Press, “Hoosiers Defeat Nebraska Cagers in Red-Hot Tilt,” San Diego Union, December 24, 1937: 14.

4 Handwritten note by Ernie Andres in his Hall of Fame player file.

5 Sam Otis, “It’s New to Most of You,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 8, 1939: 19. In a John Drohan column of last 1945, Red Sox farm director Herb Pennock was given credit. John Drohan, “Sox Get Jim Bagby,” Boston Traveler, December 12, 1945: 10.

6 American League questionnaire, found in Andres’ Hall of Fame player file. See also Tommy Fitzgerald, “Andres Now Ready for His Red Sox Bid After Four-Year Detour With the Navy,” The Sporting News, February 14, 1946: 8.

7 Associated Press, Evansville Courier and Press, January 1, 1940: 13.

8 “American Leaguers Proved They’re Still Baseball Tops,” Boston Traveler, July 8, 1942: 19.

9 Associated Press, “”Mickey Cochran Names Andres As ‘Rookie’ of the Year,” Christian Science Monitor, August 1, 1942: 11.

10 Hugh Fullerton, Jr., Associated Press, “10 Major Loop Teams Booked; Great Lakes Sailors to See Best in Major Leagues,” Morning Star (Rockford, Illinois), April 8, 1943: 11.

11 Hugh Fullerton, Jr., Associated Press, “Fear Veils Real Names,” Kansas City Star, January 1, 1944: 4.

12 “Kautskys Lose,” Evansville Courier and Press, December 10, 1945: 10.

13 Ralph Cannon, INS, “Great Lakes Nine Sends Two Youngsters to Big Leagues,” Daily Illinois State Journal (Springfield, Illinois), January 13, 1946: 13.

14 Ed Cunningham, “Andres Says He’ll Win Red Sox Post; Louisville Mates Second Motion,” Boston Herald, March 5, 1946: 18.

15 Burt Whitman, “Sox Triumph, 6-3, Over Nats,” Boston Herald, April 17, 1946: 34.

16 “Joe Cronin Lauds Team Spirit of His Red Sox,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, May 12, 1946: 9.

17 Andres interview in 2001 by Bill Nowlin. The $15,000 figure was reported in Arthur Siegel’s column in the January 27, 1947 Boston Herald, on page 20.

18 Harold Kaese, “Andres Hurt Red Sox Not Giving Him Another Trail, Wants Release,” Boston Globe, January 31, 1947: 14.

19 Associated Press, “Andres Fired As Coach,” Evansville Courier and Press, February 18, 1947: 10.

Full Name

Ernest Henry Andres

Born

January 11, 1918 at Jeffersonville, IN (USA)

Died

September 19, 2008 at Bradenton, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.