Maurice Archdeacon

A 23-year-old minor-league outfielder named Maurice Archdeacon became a well-known individual in baseball circles when he gained the title of “the fastest man in baseball” following a baserunning contest. Archdeacon’s feat came about on September 2, 1921, when the fleet outfielder attempted to circle the bases faster than the then record of 13.8 seconds set by Hans Lobert in 1910.

A 23-year-old minor-league outfielder named Maurice Archdeacon became a well-known individual in baseball circles when he gained the title of “the fastest man in baseball” following a baserunning contest. Archdeacon’s feat came about on September 2, 1921, when the fleet outfielder attempted to circle the bases faster than the then record of 13.8 seconds set by Hans Lobert in 1910.

Prior to the day’s game at Rochester’s Bay Street ball grounds, Archdeacon would be timed in a sprint around the bases by three college track officials to certify the result. The umpires for the day’s game and the opposing manager were stationed near each base to verify that Archdeacon touched the bags. His dash was timed in an amazing 13.4 seconds, breaking Lobert’s mark. In his position near third base, umpire Bill McGowan noted, “Had he not slipped and almost ruined his stride after having passed third base, it sure would have clipped some time from his mark.”1

A native son of St. Louis and of Irish parents, Maurice John Archdeacon Jr. was born on December 14, 1897.2 His parents, Maurice Archdeacon Sr. and his wife, Mary, were children when their families emigrated from County Cork, Ireland, to the United States in the mid-1880s. The senior Archdeacon eventually landed in St. Louis, where he found work as a laborer at a railroad shop. The Archdeacons lived in an Irish neighborhood, the well-known Kerry Patch of Ward 23. Young Maurice hung around the Cardinals ballpark, Robison Field, until he landed a job selling peanuts, then became visiting-team batboy and encountered Boston Braves manager George Stallings, who would play a significant part in his baseball career. However, his initial association with Stallings ended poorly. The batboy cheered so loudly for the Braves that the annoyed manager expelled the youngster from the team’s bench.

Maurice completed the eighth grade then dropped out of high school for a paying job with an electrical concern. He displayed his athletic prowess with company-sponsored amateur soccer and baseball teams. Friends and teammates often referred to him as Arch or Archie.

Archdeacon pestered an ex-minor leaguer and Cardinals scout, Charley Barrett, for a tryout with a professional team, and his persistence paid off in 1919 when he secured a spot as an outfielder for the Charleston Gulls of the South Atlantic League. Not a big fellow at 5-feet-7 and just over 150 pounds, the 21-year-old outfielder batted only .229 in 97 games. But the left-handed-batting Archdeacon was extremely fast in the outfield and on the bases, swiping 42 bags. He worked as a clerk for the Wabash Railroad during the offseason and returned to Charleston for the 1920 season.

On the way home from spring training the Boston Braves stopped off in Charleston. Manager Stallings was impressed with the speed and hustle of his former batboy, and the Braves purchased Archdeacon’s contract for delivery the next season.

Archdeacon made progress in his second year with Charleston, batting .310 and stealing 44 bases. Baseball writer John B. Sheridan declared that George Sisler was “the fastest man getting to first or anywhere else in the majors, the fastest I have ever seen I think, except a kid named Archdeacon, who is playing in the South Atlantic, and who is faster than a ghost.”3

In 1921 Archdeacon reported to spring training with the Braves but failed to stick. His mentor, George Stallings, had resigned as Boston’s manager after the 1920 season to become part-owner and manager of the Rochester International League team. Stallings purchased Archdeacon from the Braves for $4,500, the amount Boston originally paid the Charleston club.

Stallings saw potential in the young player and made Archdeacon his pet project. The manager schooled the slight left-handed hitter in the drag bunt and showed him how to choke up on the bat in order to punch a ball past a drawn-in third baseman. Stallings also instructed him to crouch at the plate to draw more walks.

Archdeacon not only was called the “Fastest Man in Baseball,” he became known by the nicknames “Flash” and “Comet.” In his first season with the Colts, Archdeacon scored 166 runs, got 202 hits, stole 53 bases, batted .325, and became a fan favorite. (Rochester won 103 games in 1921 and eclipsed the 100-win barrier for the three seasons Archdeacon was with the team, but finished second to the Baltimore Orioles each season.)

Ty Cobb’s Detroit Tigers played Rochester in an exhibition game at Americus, Georgia, on April 4, 1922. Fellow Southerners George Stallings and Ty Cobb were personal friends and had a working agreement regarding player acquisitions. Stallings touted his young center fielder to Cobb, even declaring that Archdeacon was faster that the Georgia Peach himself.

In the game at Americus, Cobb attempted to go from first to third on Bob Fothergill’s dink hit to short center field. Archdeacon’s throw beat him to the bag by 15 feet. Cobb attempted to evade the tag, but in the slide his spikes caught in the rugged surface, and he sprained ligaments in the right knee and ankle.

Within a few days, the Tigers purchased Archdeacon, for delivery at the end of the International League season. In return, Rochester got $15,000 in cash, outfielder Bob Fothergill, and another player to be named.

As the summer progressed, it became apparent that Archdeacon’s type of play was not conducive to the lively-ball style of the 1920s. Bert Walker of the Detroit News cautioned that “being able to hit .300 on all infield hits isn’t so very valuable because such hits are not likely to score men who are ahead on him and not blessed with much fastness.”4 Archdeacon batted .322 and scored 151 runs in 163 games with Rochester, but in September the deal was canceled and Fothergill was recalled to the Tigers.

Archdeacon’s outfield assists dropped from 32 in 1922 to 18 in 1923. In three years as Rochester’s center fielder he made 49 errors. He batted .357 in 162 games, but his stolen bases dropped from 55 in 1922 to 31 a year later.

There were still suitors for a speedster like Archdeacon. In September his contract was sold to the Chicago White Sox. The outfielder rushed to catch a train for Boston in order to play in his first major-league game as soon as possible. Archdeacon made his major-league debut in a doubleheader with the Boston Red Sox on September 17, 1923. In the two games at Fenway Park he had three singles, a double and a walk in 10 plate appearances. Gus Rooney of the Boston Traveler wrote: “Archdeacon is about the fastest bird that has come along into baseball for many years. He goes across first base faster than any man in the game today, and he makes second base easily on a ball that is fumbled the slightest in the outfield.”5

Archdeacon batted .402 in 22 games with the White Sox in the last three weeks of the season. Summing up the rookie’s foray in the major leagues, The Sporting News wrote, “He runs so fast you can’t count his legs.” The paper referred to Archdeacon as “the player with the $50,000 legs.”6

The White Sox already had a loaded outfield, consisting of Harry Hooper, Johnny Mostil, and Bibb Falk, so the newcomer would have to bide his time. Furthermore, Archdeacon suffered a setback in spring training due to tonsillitis, and he was still recuperating when the 1924 season began.

In Chicago’s first 11 games Archdeacon made only three plate appearances. Then on April 28 he was the starting center fielder and leadoff batter. By May 25 he had only seven hits for a batting mark of .206, and his fielding was a problem, but on the 25th Archdeacon began a hitting binge in Washington. He went 3-for-3 with a triple, and drew a walk. By the end of May Archdeacon was hitting .280. A 5-for-6 performance against Boston on June 10 raised his batting average to .366.

Archdeacon was batting .367 when he suffered a charley horse in mid-June. While resting the sore limb, he was taken ill with stomach trouble and was laid up for 10 days at his parents’ home in St. Louis. Mostil, back in center field, played well, and Archdeacon, once healthy, was relegated to the bench except for an occasional pinch-hitting appearance. Then Mostil fell and jammed his thumb so badly that Archdeacon again assumed the center-field position on July 14 in Boston.

The highlight of Archdeacon’s major-league career may have been the two games against the defending World Series champion Yankees at Chicago’s Comiskey Park on the weekend of July 26-27. Although Babe Ruth got the accolades on Saturday for his game-winning home run, Archdeacon had five hits in eight at-bats in the 14-inning marathon. Twice he bunted directly at second baseman Aaron Ward and beat both plays so easily that Ward did not even attempt a throw. Three other times he punched the ball through or over the drawn-in Yankees infield.

On Sunday, July 27, it appeared that the Yankees would capture another victory, but this time the White Sox fans in the crowd of 40,000 did not go home disappointed as Archdeacon “again drove the Yanks nuts trying to outsmart him.”7 He punched one hit past third baseman Joe Dugan into the overflow crowd for a ground-rule double, then beat out a grounder to shortstop in a two-run seventh inning, and opened the ninth with a line drive over Everett Scott’s head at shortstop to begin a rally that secured the White Sox a 7-6 victory. With three more hits, Archdeacon’s batting average zoomed from .378 to .396.

At the end of July, Archdeacon had 73 hits in 190 at-bats for a .384 average, but over the next five games he made only two hits in 21 at-bats. Though slumping, he still could rely on speed to make up for some deficiencies in the batter’s box. His favorite trick from the left-handed batter’s box was a drag bunt to the right side. Because of his speed, a second baseman could make a perfect play but still not deliver the ball to the first baseman in time. If the first baseman went after the bunted ball, Archdeacon usually beat the pitcher to first base.

Player-manager Bucky Harris of the Washington Nationals had been burned on previous occasions when Archdeacon bunted and beat the pitcher to first base. Harris decided to leave the second base position open and edge closer to first base when Archdeacon came to bat.

“The next time Archdeacon dragged,” recalled Nats first baseman Joe Judge, “I fielded the ball, turned and threw hard, and there was Bucky on the bag. We stopped Archdeacon a few times that way, and eventually he drifted out of the league.”8

Other teams adopted the same strategy and Archdeacon’s slump persisted. On August 2 he was second only to Ruth in AL batting average, but as his struggles at the plate worsened, he began to get less playing time.

Since he was not hitting, Archdeacon’s play in the outfield became problematic. In New York on August 16, Archdeacon cost his team a game against the Yankees. The White Sox led 2-1 in the ninth inning with two outs and runners on first and second. With Wally Pipp coming up, a New York Times reporter wrote, White Sox manager Johnny Evers prayed that the ball would not be hit to center fielder Archdeacon, “who can cover a given space in quicker time than anybody else in baseball but doesn’t know what to do with the ball when he arrives at the appointed spot.”9

Pipp hit a line drive to center field. Perhaps Archdeacon had a problem with the sun or just misjudged the ball’s flight. He came in a few steps then had to retreat at full speed toward the flagpole. He leaped in an effort to corral the ball, but it deflected off his glove and kept on going, the two baserunners scoring easily.

The fortunes of the White Sox mirrored Archdeacon’s failings. Chicago won only 19 games after July 31 and sank to the bottom of the standings. Archdeacon continued to struggle through September and began to get less playing time. Only in a doubleheader against Philadelphia on September 20 did he temporarily escape his two-month-long slump when he went 5-for-7 with two walks and a stolen base. He finished the season with a batting average of .319 in 288 at-bats. Archdeacon’s stolen-base numbers in the minor leagues did not translate into steals at the major-league level; in 1924 he swiped only 11 bases in 18 attempts.

In the spring of 1925, Archdeacon again was hampered by an injury during training, this time a bruised big toe. He maintained that he slipped on a cake of soap while taking a shower in the clubhouse.10 Archdeacon’s frequent injuries and maladies led to speculation that he was a “bad actor” and there was talk about drinking. The Sporting News revisited the allegation some 20 years after Archdeacon retired from professional baseball. Said the paper’s article, under the byline of publisher J.G. Taylor Spink, “‘The truth is, I’ve never had a drink in my life,’ Arch said, smiling wryly.”11

In the early stages of the 1925 season, new White Sox manager Eddie Collins used Archdeacon in only 11 games, mostly as a late-inning replacement or pinch-hitter. His only hit of the season was a pinch-hit single in the ninth inning of a game against Detroit on May 29. That was also Archdeacon’s final appearance in a major-league game. After the game Archdeacon was released to the Baltimore Orioles of the International League.

During an Orioles game on July 11 Archdeacon was knocked unconscious when he made a head-first slide into a knee of the Syracuse third baseman. He was taken to a hospital where his condition was said to be serious. It was initially feared he had dislocated a vertebra in addition to a concussion. However he quickly recovered and was released from the hospital the next day. Archdeacon was advised to rest a few days before playing, but the very next afternoon he was in the lineup for the second game of a doubleheader at Rochester and went 1-for-3.

Archdeacon helped Baltimore to its seventh consecutive International League championship in 1925, batting .310 in 98 games with 20 stolen bases. That October, Orioles owner Jack Dunn was incensed when the Washington Senators drafted Archdeacon for $5,000. The Orioles did manage to recover the center fielder in April of 1926 when the Nationals decided there wasn’t room for Archdeacon as a sixth outfielder. In exchange, Washington acquired a pair of Orioles pitchers.

That July Archdeacon was sidelined again by a severe charley horse. He managed to play in 133 games and his .328 batting average was second highest among the Orioles.

By the start of the International League’s 1927 season, Archdeacon had yet to sign his contract because it called for a pay cut. In response the Orioles suspended him. Archdeacon remained defiant and was set to leave the team for his home in St. Louis when the two sides came to terms a week into the season. As in the previous season, his .338 average was second best among the Orioles.

Dunn’s sale of Baltimore’s best players combined with the major leagues’ draft of International League players dropped the Orioles into fifth place in 1927. They finished fifth again in 1928 but Archdeacon was not around to experience the decline. Eight days into the season Dunn sold him to Buffalo for $3,500.

On June 23, 1928, Archdeacon was the last person to bat against Walter Johnson in Organized Baseball. The occasion was Walter Johnson Day in Newark to honor the great pitcher and to welcome him as new manager of the local International League club. Archdeacon led off and Johnson walked him. The fourth ball was the last pitch Johnson would throw in Organized Baseball.

Archdeacon played in 142 games with the Bisons, batting .299. He split the 1929 season between Atlanta (Southern Association) and Toronto (International League), playing in 84 games altogether. Archdeacon batted .265 in 60 games with Toronto and .234 in 24 games for Atlanta. He suffered a split hand the latter part of the season that kept him out of the game for several weeks. Archdeacon married Eleanor Lyons in November and the couple left their hometown of St. Louis for California. When Archdeacon requested a trade to a Pacific Coast League club, Toronto didn’t even bother to seek a trade and gave the declining outfielder his unconditional release.

In 1930 Archdeacon played in 33 games with Pittsfield (Massachusetts) of the Eastern League before he was released in May. He did not play in Organized Baseball the following season, but his name made the newspapers in 1931 when Evar Swanson of the Cincinnati Reds bested his baserunning record by one-tenth of a second.

In February 1932 Archdeacon signed with the Dubuque (Iowa) Tigers of the Class D Mississippi Valley League. Though he missed two weeks in June with a lacerated thumb, he played in 112 games and batted .337, the second best average in the league. In August he was named manager of the Tigers for what remained of the season.

“I was manager, water boy, president and outfielder,” Archdeacon said with a chuckle. “I decided that I had hit bottom and hung up my spikes at the end of the season.”12

Having ended his professional baseball career, Archdeacon and Eleanor returned to St. Louis, where he operated a tavern and secured government jobs as an auditor and as a purchasing agent for the Army Engineers. In April 1947 Archdeacon became a part-time scout for the New York Yankees in St. Louis and southern Illinois. In January 1950 he joined the St. Louis Browns as a scout, a position he held until the club moved to Baltimore after the 1953 season.

Archdeacon died on September 5, 1954, after an extended illness. His funeral was held at St. Luke Catholic Church in Richmond Heights and he was buried in Memorial Park Cemetery, St. Louis County. He was survived by his wife, father, and a younger sister.

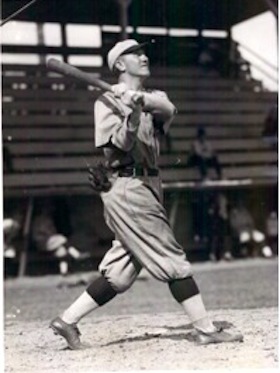

Photo credit

Maurice Archdeacon, Charleston, March 30, 1921 (Sporting News Collection)

Sources

Besides the sources cited in the notes, the author also consulted the following:

Thomas, Henry W. Walter Johnson: Baseball’s Big Train (Washington, DC: Phenom Press, 1995), 307.

Detroit Free Press.

Reading Eagle.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Syracuse Herald.

Ancestry.com.

Notes

1 # Bill McGowan, “Calling ’Em in the Bushes,” Delmarva Star (Wilmington, Delaware), May 9, 1924: 16.

2 Sources, including census records, conflict on Archdeacon’s year of birth. Recent baseball encyclopedias say 1898, but earlier editions gave 1897. In a sworn, handwritten statement on his World War I draft registration card, Archdeacon said he was born on December 14, 1897.

3 The Sporting News, June 24, 1920: 4.

4 Ibid.

5 The Sporting News, September 27, 1923: 2.

6 “Maurice Archdeacon,” The Sporting News, October 4, 1923: 1.

7 “Injuries Set Back Both Sox and Cubs,” The Sporting News, July 31, 1924, 1.

8 “Wig-Wag Wizard Harris Flashes His Sign System,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1946: 4.

9 “Yanks Win in 9th on Triple by Pipp,” New York Times, August 17, 1924: 25.

10 “Archdeacon Stubs Toe,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 29, 1925: 43.

11 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Looping the Loops,” The Sporting News, February 1, 1950: 6.

12 “Archdeacon, Ex-Stallings Ace, Visits Friends Here,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, July 13, 1939: 19.

Full Name

Maurice John Archdeacon

Born

December 14, 1898 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

September 5, 1954 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.