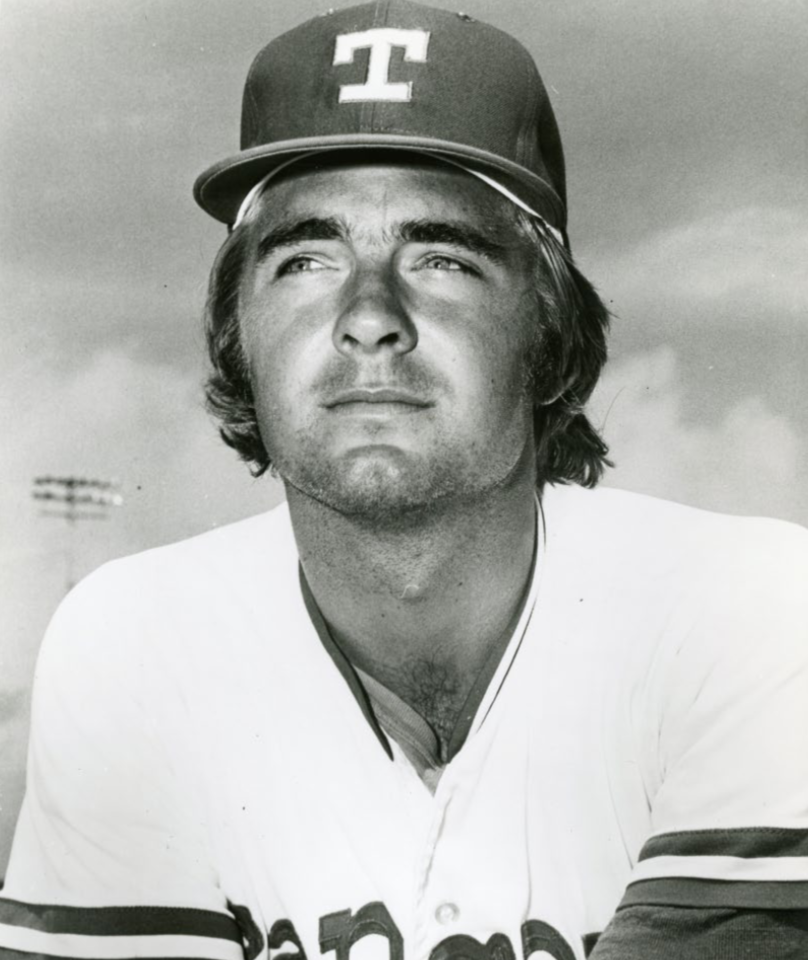

Pete Broberg

“It was all so new,” reminisced Pete Broberg about suiting up for the Texas Rangers in their inaugural season in 1972. “A new city, new stadium, a new look. We weren’t wearing the flannels anymore; we had the new stretchy ones.”1 It was the dawn of a new era in football-crazed Texas as the Washington Senators relocated to Arlington, a suburb of Dallas-Fort Worth. Broberg, a hard-throwing right-hander who joined the Senators straight from the campus of Dartmouth College the previous season, holds the distinction of winning the first game (April 16) and tossing the first shutout (April 22) in Rangers’ history. “I liked pitching there – anywhere where there was humidity,” said Broberg. While NL players enjoyed the comfort of the climate-controlled Houston Astrodome, players in the AL were introduced to the Texas summer heat.

“It was all so new,” reminisced Pete Broberg about suiting up for the Texas Rangers in their inaugural season in 1972. “A new city, new stadium, a new look. We weren’t wearing the flannels anymore; we had the new stretchy ones.”1 It was the dawn of a new era in football-crazed Texas as the Washington Senators relocated to Arlington, a suburb of Dallas-Fort Worth. Broberg, a hard-throwing right-hander who joined the Senators straight from the campus of Dartmouth College the previous season, holds the distinction of winning the first game (April 16) and tossing the first shutout (April 22) in Rangers’ history. “I liked pitching there – anywhere where there was humidity,” said Broberg. While NL players enjoyed the comfort of the climate-controlled Houston Astrodome, players in the AL were introduced to the Texas summer heat.

Peter Sven Broberg was born on March 2, 1950, in West Palm Beach, Florida, to Gustave T. Broberg Jr. and Mary Stewart (Colwell) Broberg. The elder Broberg, whose parents emigrated from Sweden, was an attorney and municipal judge in the seaside town. An All-American basketball player at Dartmouth College and three-time Ivy League scoring champion (1939-1941), Gus Broberg was also accomplished outfielder. He turned down an offer from the New York Yankees to join their farm system in order to enlist in the Marines during World War II. As a pilot he lost his right arm in a crash in Okinawa, but he never lost his love for baseball. “My father, overtly or subliminally pushed me into baseball, and I stayed with it,” Broberg the younger told the author. “We’d throw the ball to each other. He’d catch it with his left hand, sling off his glove and throw the ball back to me. He could bat one-handed, and hit popups to me.”

By the time Broberg was about 14 years old, he began to recognize his baseball talents. “Tom Howser – Dick’s brother – was my coach in Babe Ruth ball. He was a big influence and showed me how to pitch,” said Broberg. Over the course of the next four years, Broberg established his reputation as a flamethrowing sensation pitching for West Palm Beach High School and American Legion Post 12. He regularly racked up double-digit strikeout totals, and once whiffed 23 while hurling nine perfect innings, but getting a no-decision.2 Big-league scouts were commonplace in the fertile grounds of South Florida, but Broberg did not remember talking to any as a prep phenom, though he knew they were on his trail. Just weeks after graduating from high school, Broberg was selected by the Oakland A’s with the second overall pick in the amateur draft, on June 7, 1968. “I was playing in the American Legion state tournament,” he recalled. “There was a pretty good crowd and I threw a perfect game with all of the scouts there. That was probably one of the reasons they drafted me out of high school.”

After several weeks of negotiations with A’s owner Charles O. Finley, Broberg made national headlines when he turned down a reported signing bonus of $175,000 and enrolled at Dartmouth. “I don’t remember being pushed one way or the other to sign or go to college,” Broberg explained. “It was my own decision.”

Broberg fell under the tutelage of Tony Lupien, longtime head baseball coach at Dartmouth. “He played with the Red Sox [in the early 1940s],” said Broberg. “I felt that he knew the ropes to the big leagues, and that’s why I always asked him questions. He was a tough old timer.” As a sophomore Broberg led the school to its first-ever College World Series. He struck out 11 against Florida State, but the Big Green committed six errors and lost, 6-0, in the second round.3 Broberg gained additional experience as a member of the Fairbanks Goldpanners and played against many of the top prospects in the country in the Alaska Summer League in 1969 and 1970. “[The league] was touted as being better than the Cape Cod League,” said the pitcher. “I agreed [to play] if I could bring a friend. I brought Charlie Janes, another pitcher for Dartmouth. We were the first players east of the Mississippi to play there.” United Press International reported that Broberg had the “attention of every major-league scout in the business” by the end of his junior year.4 “[He’s] the fastest pitcher I’ve seen since Bob Feller,” said Lupien of his prized right-hander, who fanned 127 in 82 innings (including 20 in a game against Boston College) and finished with a 1.42 ERA in 1971.5

The Washington Senators selected Broberg with the first overall pick of the secondary phase of the 1971 amateur draft (for players who had already been drafted and refused to sign). “I was honored to be chosen,” said Broberg, who clarified his behind-the-scenes pre-draft negotiations with both Washington and the Boston Red Sox. “[Boston] wanted me to turn down [Washington owner] Bob Short and fall to them. That was very tempting and in hindsight perhaps I should have done that. But Washington was going to send me to the big leagues and the Red Sox were going to send me to [Triple-A] Pawtucket. The choice was easy.”

“The countdown has started,” wrote the Associated Press, speculating on when and if the Senators could sign Broberg, who once again was in the national spotlight.6 But there was never any doubt in Broberg’s mind where he would be. Twelve days after the lowly Senators drafted him, the flamethrowing right-hander made his major-league debut on June 20 in front of just under 20,000 spectators at Robert F. Kennedy Stadium in Washington. Broberg put on a “formidable exhibition,” mused the AP, holding Boston to just two runs (both earned) in 6⅓ strong innings but got a no-decision in Washington’s eventual 4-3 defeat.7 “I wasn’t nervous,” reminisced Broberg, who threw 97 pitches.8 “I was leading the game when they took me out. I called my dad and told him I had seven strikeouts, but man, I gave up three hits.”

After losses in his next two starts, Broberg went on a roll, winning five of his next eight starts. During that impressive stretch of 59⅔ innings, he sported a nifty 1.81 ERA, held opponents to a .208 batting average, and completed four games, including a five-hit shutout against Cleveland. Broberg drew rave reviews: “That kid has a tremendous fastball and has tremendous poise for his lack of experience,” said Jim Lonborg, former Cy Young Award winner with Boston.9 Jim Spencer of the California Angels claimed, “He throws harder than Vida Blue.”10 Even manager Ted Williams, notoriously hard on his own pitchers, chimed in: “I’ve never seen a more impressive youngster come into the league.”11 But Broberg had little room for error on a team that averaged just 3.38 runs per game . He lost his final six decisions (Washington tallied just 12 runs) to finish with a 5-9 record and 3.47 ERA in 124⅔ innings while the Senators limped to a 63-96 record, good for fifth in the six-team AL East.

Like most pitchers who played for Ted Williams, Broberg’s relationship with his manager was curt and to the point. “We didn’t talk much,” admitted Broberg. “Williams said a few nice things about me to the papers after my first few starts, but not to me.” He added that Williams showed little concern and sometimes outright contempt for pitchers. Broberg recounted the time he first met Williams in the Senators’ clubhouse. “I was told that Williams would ask me if I know what makes a curveball curve.” Not one to play the deferential rookie pitcher to the living legend, Broberg promptly told William the answer. “Williams walked off in a harrumph after that,” chuckled Broberg. “I don’t think he liked it.”

Broberg responded resolutely when asked if he felt pressure about jumping from college to the big leagues in 1971: “That’s where I felt I should be in my natural progress. It was a comfortable state and I felt at home. I really don’t think that starting in the minor leagues would have helped my career. I think some more understanding and benevolent coaches could have done a better job for me.” Looking back on his big-league career, Broberg praised Sid Hudson, his pitching coach with Washington/Texas in 1971-72, as the exception to the rule.

Described by sportswriter Red Smith as “large, long haired, good looking, blond, personable, and rich,” the 6-foot-3, 205-pound Broberg commanded the mound.12 Often sporting fashionable sideburns, he relied on a three-quarters to overhand fastball to overpower hitters; he occasionally dropped to a side-arm delivery to right-handed hitters. He also threw a 12-to-6 overhand curve and a hard slider. “The pitch I wish I had learned was the circle change,” Broberg confessed, referring to pitcher John Smoltz, who mentioned in his Hall of Fame induction speech in 2015 that the pitch was the difference maker in his career. “I think that is one of the greatest pitches ever invented,” said Broberg, and added, “I never learned a good changeup.” Broberg also looked back in awe of Bruce Sutter’s split-finger fastball. When the two were teammates in 1977 with the Chicago Cubs, Broberg tried in vain to learn the pitch from coach Fred Martin, who taught it to Sutter.

The cash-strapped Washington Senators’ 11-year tenure in the nation’s capital came to a conclusion on September 21, 1971, when American League owners voted 10-2 to allow Bob Short to relocate the team to Arlington, Texas. “I don’t think I even knew about the move until the last few games of the season when it was announced,” said Broberg. “It wasn’t a distraction for me.”

Rechristened the Texas Rangers, in honor of the state’s famous law enforcers and to establish an identity as Texas’s baseball team, the club played its games in Arlington Stadium. “The stadium was like an Erector Set,” joked Broberg about the former Turnpike Stadium where the Double-A Dallas-Fort Worth Spurs had played beginning in 1965. “It was just a minor-league stadium with more seats in the outfield and a big scoreboard. But I liked pitching there.”

Broberg got off to a hot start in 1972. After the Rangers’ tough-luck, 1-0 loss to the California Angels in the season opener, Broberg collected the first win in the history of the relocated franchise by limiting the Angels to just five hits over eight innings in a 5-1 victory at Anaheim Stadium. In his next start, he tossed the first shutout in Rangers’ and Arlington Stadium’s history. Praised by the AP for his “crackling fastball and a whipping curve,” Broberg blanked the Angels on four hits. “He’s getting confidence and he’s going more to the slider and curve,” said Ted Williams. “You can see him getting better and better.”13 While the Rangers proved that their early-season success by sliding to the AL West basement, Broberg improved his record to 5-4 and lowered his ERA to 2.66 on June 13 with arguably the best game of his career, a three-hit shutout of Milwaukee in Arlington. The victory was even more impressive considering that Broberg had just returned to the team after graduating from Dartmouth two days earlier. And then the roof caved in.

Broberg’s degree in economics could not help the Rangers’ hitting, which was dismal even by the depressed offensive output of the era. The club batted just .217, the second lowest average in the AL in the Live Ball era, and scored an average of 2.99 runs per game. After Broberg’s three-hitter, the Rangers lost 70 of their next 102 games. Broberg lost his next eight decisions, and finally his spot in the rotation. Pitching out of the bullpen and primarily in mop-up situations in the last two months of the season, he concluded a once promising campaign with a 5-12 record and a 4.29 ERA in a team-high 176⅓ innings; he started 25 of a career-high 39 games. Though he ranked eighth in strikeouts per nine innings (6.8) and whiffed a career-high 11 over 7⅓ innings in a no-decision against Chicago on June 24, he also battled control problems in 1972, ranking third in walks issued per nine innings.

In the offseason, Broberg played for Aguilas del Zuila in the Venezuelan Winter League. “Rich Billings, the Rangers catcher, was the manager for Aguilas and asked me to come down and play. That’s how it started,” said Broberg who posted a 6-3 record and 1.73 ERA in 96⅓ innings. “I played for Leonas del Caracas (1974-1975) and Tigres de Aragua (1976-1977). They were good experiences, though Caracas was a little nerve-racking at times.”

“People have a tendency to black out memories they don’t want to remember,” Broberg responded when asked about his second season with the Rangers. The 1973 club finished last in scoring and last in team ERA, a toxic mix that produced a franchise worst 57-105 record. New manager Whitey Herzog, a brash 41-year-old, vowed to mold the team with old-school discipline, but his approach alienated players, including Broberg. “Herzog and I did not get along,” said the pitcher bluntly. Broberg got off to a rough start, losing his first four decisions, before tossing a complete game to defeat Cleveland, 3-2, on May 30 his first victory in almost a year. Broberg seemed to get on track in June, winning three straight starts; however, he felt he never gained Herzog’s confidence. After a nightmarish relief outing on July 4, Broberg was unceremoniously optioned to Spokane in the Pacific Coast League. By the time he was recalled in September, Herzog had been fired and another firebrand, Billy Martin, had been hired. Known for giving his pitchers a long leash, Martin reinserted Broberg into the rotation. Broberg concluded the campaign by tossing a nifty seven-hit shutout against Kansas City for a 5-9 record and 5.61 ERA in 118⅔ innings.

In his first full season with Texas, Billy Martin transformed the club from the laughingstock of the AL to a division contender, finishing in second place with a then-team record 84 victories. The club was led by Jim Sundberg, Mike Hargrove, Toby Harrah, and MVP Jeff Burroughs, each 25 years old or younger. Broberg, after dealing with trade rumors most of the offseason, spent the campaign shuttling between Texas and Triple-A Spokane, and never found his rhythm on either team. Despite an 0-4 record and 8.07 ERA in just 29 innings over 12 appearances (two starts) with the Rangers, he maintained he never lost his confidence, even when he was demoted. “I never had one of those ‘What’s happening? What am I going to do tomorrow?’ moments,” said a reflective Broberg. “I was playing baseball and getting paid. We rolled with the punches.” Broberg’s tenure with the Rangers ended on December 5, 1974, when he was shipped to the Milwaukee Brewers in exchange for pitcher Clyde Wright.

The 25-year-old hurler looked forward to a fresh start in Milwaukee and the chance to escape Texas, where he thought he had not had a chance to pitch regularly the previous two years. “He can pitch,” said skipper Del Crandall of Broberg, “but he has to convince me that he can be a consistent pitcher.”14 And Broberg quickly did. Earning a spot in the rotation, he held Boston to four hits (three runs) in 6⅓ innings to win his first start, on April 9. He concluded his first month in Beer City by tossing a stellar three-hit shutout against the New York Yankees at Shea Stadium (where the club played in 1974-1975 while Yankee Stadium was being renovated). In that game Hank Aaron knocked in his 2,209th run to tie Babe Ruth’s record. (Ruth’s RBI total has since then been adjusted.) Described by beat writer Lou Chapman as “Milwaukee’s nearest version of a stopper,” Broberg was arguably the biggest surprise on the 94-loss club.15 After a rough patch in late July, Broberg unveiled a new no-windup delivery in a complete-game three-hit loss to Oakland on August 17. In his final 10 starts of the season, Broberg posted a sturdy 2.85 ERA in 79 innings, yet won just four times for the low-scoring Brewers. During that stretch he tossed a career-high 10⅓ innings against the Yankees, yielding two earned runs to pick up the loss; and blanked Detroit on six hits to record the sixth and final shutout of his career.

“I played for my favorite manager, Del Crandall,” Broberg responded when asked about his seemingly unexpected turnaround. “Instead of pitching and looking over my shoulder and wondering if the pitching coach or manager was going to come get me the first time I walked somebody, Del said I’d pitch every four days.” In what proved to be the first and only time Broberg pitched in the starting rotation for a full season, the big right-hander set career highs in practically every category, including starts (32), innings (220⅓), and wins (14); he also led the AL in hit batters (16), and issued 106 walks. A tough-luck loser, Broberg was saddled with 16 defeats; however, in 14 of them Milwaukee scored just 17 total runs.

Although Broberg had paced the Brewers in most pitching categories in 1975, new manager Alex Grammas was unimpressed in 1976. Citing Broberg’s control problems in spring training, Grammas relegated the right-hander to swingman to start the season. Insulted, Broberg felt that he had earned a chance start regularly. “Alex and I didn’t get along,” said Broberg bluntly. “They wanted to tinker with my motion and windup. I lost a couple close ones in the beginning, and all of a sudden I wasn’t getting a lot of work.” Broberg lost three straight starts despite yielding just four earned runs in 19⅔ innings to fall to 1-4 on May 27. After dropping his fifth straight decision, on June 5 (three earned runs in six innings against Kansas City), Broberg was shunted to the far end of the bullpen and made only 12 more appearances (three starts) the rest of the season. He finished with a 1-7 record and 4.97 ERA in 92⅓ innings.

Left unprotected in the major-league expansion draft in November 1976, Broberg was selected by the Seattle Mariners with the 35th overall pick. Broberg can be seen in an airbrushed Mariners cap on his 1977 Topps baseball card, but he never actually pitched a regular-season game for the club. Near the end of spring training, Broberg was designated for assignment;16 however, the Mariners had only a short-season Class A minor-league team. “Seattle loaned me to Wichita, the Cubs Triple-A team,” explained Broberg, whose anticipated journey back to the big leagues was shorter than expected. “I pitched against the Cubs in an exhibition game and had a lot of strikeouts, and then the Cubs traded for me.” On April 20 Chicago acquired Broberg. (Jim Todd was shipped to Oakland on October 25 to complete the deal.) Assigned officially to Wichita, Broberg was recalled in early July. He made 22 relief appearances, often in mopup situations, and logged 36 innings.

Broberg looked forward to camp with the Cubs in 1978 and an opportunity to prove that he was still a capable starting pitcher. “I was having too good of a spring and [the Cubs] didn’t know what to do with me,” said Broberg of his unexpected trade to the Oakland A’s on March 29 for utilityman Rodney Scott and cash. “The Cubs had used me a reliever, and they didn’t know what person they’d bump out of the rotation.” Defying expectations, Broberg resurrected his career yet again by scattering four hits over 7⅓ scoreless innings against Seattle to win the first of four consecutive decisions. With a record of 9-6 (3.53 ERA) on July 3, Broberg seemed headed for his best year as the surprising A’s challenged for the AL West crown, just 1½ games off the pace (41-39). But as Oakland slumped the rest of the season to finish in last place, so too did Broberg. He went winless in his next 10 starts (11 appearances), posting a 6.85 ERA and logging just 44 , and was relegated to the bullpen. In a spot start in the second game of a doubleheader against Texas at Arlington Stadium on September 10, Broberg tossed a four-hit complete game to win, 4-1, in what proved to be his last big-league victory. He finished with a 10-12 record and 4.62 ERA in 165⅔ innings.

Just 28 years old, Broberg signed with the Los Angeles Dodgers as a free agent in 1979. “When the general manager [Al Campanis] told me they wanted to send me down, I asked about my other options,” explained Broberg. “He tells me I can have my outright release. So I said just give it to me. I was released on Opening Day.” The Dodgers were forced to pay Broberg his entire $65,000 salary instead of just a portion of it. But it turned out to be a blessing in disguise. Three years earlier, Broberg had been accepted to law school and received notice that he could no longer defer matriculation. That fall he began his law studies at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Spending April at home in Palm Beach for the first time since his high-school days, Broberg turned down offers from the New York Mets and Seattle Mariners, who offered him the league minimum to pitch. “When they told me that they wouldn’t pay for my apartment or help with those kinds of expenses, I told them that it would cost me more money to play ball than stay at home and start law school in the autumn. And that’s what I did.”

In parts of eight seasons in the big leagues, Broberg fashioned a 41-71 record, started 134 of 206 games, and posted a 4.56 ERA in 963 innings. He never suffered a baseball-related injury, but admitted with a chuckle, “I got my ego bruised.” He toiled for primarily terrible teams which finished in last or next to last in six of his eight seasons. “It’s a real distraction,” said Broberg candidly about playing for poor ball clubs. “Guys come to the ballpark expecting to lose and that’s not a good mindset. Teams I played for were 198 games under .500. A bad statistic – but the actual one.”

Asked about his most vivid memory in his major-league career, Broberg gave a surprising response. “Ted [Williams] was a surly guy,” he began, and then reminisced about a hitting contest and fundraiser in support of the Jimmy Fund cancer charity prior to a game between the Texas and Boston at Fenway Park on August 25, 1972. “Finally it’s time for Ted to hit – he’s hitting last,” said Broberg. “He takes off his jacket and has his big belly hanging down. He goes up to the bat rack, going around looking for a bat. And then turns around to us in the dugout and says ‘No wonder you fucking guys can’t hit.’” Just shy of his 54th birthday, Williams popped up a few before the scene changed dramatically. “You could hear him yell at the batting practice pitcher [Boston’s pitching coach Lee Stange], ‘throw the fucking ball harder.’ ” recalled Broberg. “Williams started hitting line drives all over Fenway and into the seats. It was unbelievable to watch him hit.”

As of 2015, Broberg has lived his entire life in Palm Beach. In July 1975 he married local resident Beverly Deitz, and together they raised two children, Erik and Elizabeth. Following his father’s footsteps, Broberg became a successful attorney, focusing primarily on estate planning and real estate, and a partner in the law firm of Coe & Broberg. He has been active in the community, and has served as director of the Palm Beach Chamber of Commerce, chairman of the local recreation committee, and member of the planning and zoning board for the town.

Inducted with his father into the Palm Beach County Sports Hall of Fame in 1984, Broberg never lost his passion for baseball. He briefly revived his career when he played for the West Palm Beach Tropics in the short-lived Senior Professional Baseball Association in 1989. He often pitched batting practice to his son’s high-school baseball team, and participated in reunions and old-timer’s games with his former teams. In 2000 he was one of the guest speakers at SABR’s national convention in West Palm Beach.

As of 2015, Broberg lived with his wife in Palm Beach.

The author expresses his gratitude to Peter Broberg whom the author interviewed on July 29, 2015. Broberg subsequently read this biography to ensure its accuracy.

This article was published in “The Team That Couldn’t Hit: The 1972 Texas Rangers” (SABR, 2019), edited by Steve West and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 All quotations from Pete Broberg are from the author’s interview with the player on July 29, 2015.

2 “Indians Outlast PB Broberg, 1-0,” Fort Pierce (Florida) News Tribune, March 25, 1968.

3 Charles Chamberlain, “Two Undefeated Teams in NCAA Baseball,” Indiana (Pennsylvania) Gazette, June 15, 1970: 19.

4 UPI, “Pete Broberg Is Draft Bait,” Zanesville (Ohio) Times Recorder, May 13, 1971: 8-B.

5 Ibid.; Season statistics from Dartmouth Big Green Baseball, dartmouthsports.com/ViewArticle.dbml?ATCLID=205122513. Twenty strikeouts from Will Parrish, “Broberg Ready to Give Pro Ball a Whirl,” Palm Beach (Florida) Post, May 28, 1971, D4.

6 AP, “Senators Made Pitcher No. 1 Pick in Draft,” Salisbury (Maryland) Times Daily, June 10, 1971: 17.

7 AP, “Broberg Makes Sox Believers; Bonus Baby Lives Up to Name,” Lowell (Massachusetts) Sun, June 21, 1971: 40.

8 Pitch count from “Williams Happy; Broberg Dissatisfied by Debut,” Palm Beach (Florida) Post, June 21, 1971: C1.

9 Larry Eldridge, AP, “Pete Broberg Impresses Ted,” Cumberland (Maryland) Evening Times, June 30, 1971: 38.

10 AP, “One Pitch Beats Broberg,” The Capitol (Annapolis, Maryland), August 25, 1971: 19.

11 Ibid.

12 Red Smith, “Sports of the Times. Walter Johnson II,” Warren (Pennsylvania) Times-Mirror and Observer,” March 21, 1971: 8

13 AP, “Peter Broberg. Ted Williams Expects Assist From Pitcher,” Lubbock (Texas) Avalanche-Journal, April 25, 1872: 12.

14 Joe Saggis, UPI, “Team Sizeup: Milwaukee Brewers,” Raleigh Register (Beckley, West Virginia), March 17, 1975: 1.

15 Lou Chapman, “Broberg Must Prove Self to Join Starting Rotation,” Milwaukee Sentinel,” April 7, 1976: 1.

16 AP, “Pete Broberg Sent to Cubs,” Progress Bulletin (Pomona, California), April 20, 1977: 41.

Full Name

Peter Sven Broberg

Born

March 2, 1950 at West Palm Beach, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.