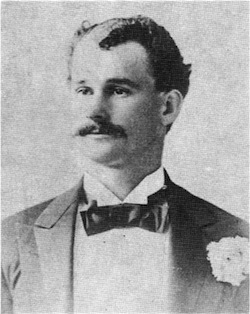

Bill Hawke

From his early days as an amateur, pitcher Bill Hawke mowed down opposing batsmen with a lightning quick fastball and tantalizing off-speed pitches. When the distance between the batter and pitcher was expanded to 60 feet, 6 inches in 1893, Hawke changed his strategy and began to induce outs with grounders and pop flys. In addition to his overpowering heater, Bill’s pitching arsenal consisted of what baseball writers of the day described as “drops and shoots.” Hawke himself used the term “sinker” when describing his deceptive drop ball to a reporter from the Baltimore Sun.

From his early days as an amateur, pitcher Bill Hawke mowed down opposing batsmen with a lightning quick fastball and tantalizing off-speed pitches. When the distance between the batter and pitcher was expanded to 60 feet, 6 inches in 1893, Hawke changed his strategy and began to induce outs with grounders and pop flys. In addition to his overpowering heater, Bill’s pitching arsenal consisted of what baseball writers of the day described as “drops and shoots.” Hawke himself used the term “sinker” when describing his deceptive drop ball to a reporter from the Baltimore Sun.

A severely broken wrist put an end to his big league career after only three seasons. Modern medical treatment would have had Hawke back in the lineup in a few months, but sadly this would not be the case for the man who threw the first major league no-hitter at the present-day pitching distance.

William Victor “Bill” Hawke was born in Elsmere, Delaware, on April 28, 1870. His parents were John and Jane Hawke, and the 1870 census shows him as the youngest of seven children. Bill attended public school in Wilmington, Delaware, until the age of fourteen. At that time, he got a job at a local wheelwright’s shop. Later on, he was employed at a Morocco factory1.

Bill, who was occasionally referred to in some newspaper accounts as Dick Hawke2, first made his mark on the diamond as a third baseman and catcher for the Defiance team out of Wilmington. By 1889, he had moved on to a nine from nearby Middleton. The following season, he joined the Elkton, Maryland, club and became a pitcher, striking out 20 of his former Middleton teammates in a nine-inning game. During this time, Hawke also pitched for a team from Chestertown, Maryland.

On July 2, 1891, the Baltimore Sun noted that Oriole vice- president Billy Waltz received a letter from what was described in the newspaper as “a well known resident of Elkton,” recommending Hawke for the Baltimore pitching staff. The dedicated Oriole fan wrote that the previous Saturday, Hawke, who was pitching for Elkton, threw a no-hitter against a very talented ballclub from Chester, Pennsylvania, striking out 23 men. A previous dispatch to the Sun that had been received on the evening of July 1 noted that earlier in the day, Hawke shut out a team called the Columbias from Wilmington, Delaware, 19-0, fanning 20 batters in the process.

The Baltimore Orioles, who were playing in the American Association at this time, were not keen on signing amateur pitchers and rushing them into the fast-paced competition of major league baseball. Bill didn’t sign with Baltimore, although an article in the July 6 Baltimore Sun noted that he was offered a trial by Orioles manager Billie Barnie but hadn’t undecided whether he would accept. Hawke eventually chose not to sign with Baltimore.

On August 8, Hawke led Elkton to 2-0 victory over the Rising Sun club for the championship of Cecil County, allowing just three hits while striking out 24 batters. On August 12, he struck out 26 men in a 13-inning contest while pitching for an aggregation from Pocomoke City, Virginia. Three days later, Bill was back pitching for the Elkton nine in a 5-3 loss to a local Baltimore team called the Pastimes at Union Park. In regard to Hawke’s pitching that day the Baltimore Sun of August 17 noted a few days later, “Hawke has good speed, curves and control and made a favorable impression.”

The following week, the speed-baller posted 19 strikeouts in a game against the Schuylkill Navy Yard team and soon after whiffed another 16 batters in an 18–3 victory over New Castle.

With performances like this, it did not take long for minor league teams to come calling. In late May of 1892, Bill inked his first professional contract with the Reading Actives of the Pennsylvania State League for an annual salary of $1500. Hawke’s brother Harry, who was a catcher, joined the team on June 27.

In regard to Bill Hawke signing with Reading, The Chestertown Transcript of June 16, 1892 wrote,“ He differs from most professional ball players, in that he is quiet and gentlemanly, two qualifications too seldom found in professional players.”

When the Actives folded in July, the Delaware native joined back up the Pocomoke City team. One of the games Hawke pitched for Pocomoke was an 18-inning victory over Norfolk in which he struck out 29 opposing batsmen.

A short time later, Hawke traveled to Baltimore to inquire about a pitching job with the major league Orioles. When he arrived at Union Park, the Baltimore front office made it clear that they were not interested in his services. At that point, Bill walked over to the visiting St. Louis Browns’ clubhouse to ask for a tryout. By chance the Browns’ scheduled starting pitcher Kid Gleason had come down with a sore arm and the team needed an immediate replacement. Due to their pressing need for someone to fill Gleason’s place in the rotation, St. Louis owner Chris von der Ahe agreed to give Hawke a trial.

Shaking off any nerves he may have had regarding his first major league start, the 5’8,” 169-pound Hawke strode out to the pitcher’s box and went to work. As it turned out, Bill had his good stuff that afternoon. He gave up four hits and struck out four while leading the Browns to a 2-1 victory over the team that turned him down earlier in the day. This stellar performance earned him a permanent contract with St. Louis for the rest of the season. In regard to Hawke’s pitching the previous day, the Baltimore Sun of July 29, 1892, wrote, “He has good curves, fine speed and above all, excellent control of the sphere.”

After spending about a month with the Browns, Hawke left the ballclub in Baltimore and went back home to Wilmington and sat out the season after a disagreement over a fine that was levied upon him by owner Chris Von der Ahe3. Bill compiled a record of five wins and five losses to go along with a 3.70 earned run average for a St. Louis club that finished 11th in the 12-team National League. Hawke eventually joined back up with the Elkton squad for the remainder of the 1892 campaign.

Over the following winter, the Browns hired former major leaguer William Henry “Watty” Watkins as their new manager. Part of his preseason duties were to settle any past differences between Von der Ahe and some of the players on the team. In the next few weeks, Watkins made trips around the country signing new players while visiting a number of disgruntled Browns including Jack Glasscock, King Crooks, Kid Gleason, and Hawke. After a lengthy meeting with Watkins in Wilmington, Bill agreed to play for the Browns.

In order to give the hitters of the day a better chance, the pitcher’s rubber was moved from 55 feet to 60 feet 6 inches from home plate at the start of the 1893 season4. This led to higher batting averages and more scoring throughout baseball, making the games more exciting for the fans.

That spring, Hawke didn’t report to the Browns because of a disagreement over his salary for the upcoming season. After a brief holdout, Bill eventually came to terms with the St. Louis club and agreed to join the team. Upon his arrival, he immediately made his presence known, striking out 12 men in an April 8 exhibition game against a local amateur club.

As it turned out, Von der Ahe was still harboring ill feelings towards Hawke, presumably for walking out on the team the previous year or possibly his more recent preseason holdout. Whatever the reason, after trying to sell Hawke’s contract to Baltimore for $500, Von der Ahe released him after just one unsuccessful start.

Bill was given his ten days’ notice by the Browns on May 14. Von der Ahe was going with Kid Gleason (21-22), Pink Hawley (5-17), Ted Breitenstein (19-24) and John Dolan (0-1) as his starting pitchers so he felt that Hawke was expendable. When Baltimore manager Ned Hanlon heard that the right-hander might be available, he told a reporter for the Baltimore Sun, “I did not know of Hawke’s release, but if he can come we will take him as a member of the Oriole team.” True to his word, Hanlon signed him to a contract a few weeks later.

In his first start with Baltimore on June 9, Hawke bested Hall of Fame first baseman Cap Anson’s Chicago Colts 11-9. For the next two months, his work for Orioles was credible but not spectacular. It also soon became apparent that the headstrong pitcher was not enamored with the pitch calling of Oriole catcher Wilbert Robinson. On July 3,1893, the Baltimore Sun observed, “ If Hawke would follow Robinson’s instructions as to what kind of balls to pitch he would be 50 percent more effective than he is.”

There is no way to know if he started taking Robinson’s advice, but the burly backstop was behind the plate on Wednesday August 16, 1893, when Hawke became the first man to toss a no-hitter from the new pitching distance. The Orioles defeated the Washington Senators 5-0 that day as Bill’s drop ball worked with pinpoint accuracy. His overwhelming command of this elusive pitch led to a number of Senators tapping the ball weakly to a waiting Oriole infielder or popping up an easy fly to one of the Baltimore outfielders. Hawke also took care of a few of the Washington batsmen himself, striking out six Senators and making one putout from the pitcher’s box. Hawke, who was a bit superstitious, attributed his good luck that day to a new felt hat that he recently purchased. He finished the 1893 season with a record of 11 wins and 16 losses for a Baltimore team that finished eighth in the National League.

Pitching from a greater distance and facing professional batsmen instead of amateurs, Hawke was no longer racking up high strikeout totals. Instead, he pitched to contact and let his fielders do the rest. Even so, his 2.74 strikeouts per every nine innings was still the fifth highest in the National League.

In late February 1894, Bill declined to join the Oriole team when it left Baltimore for its southern spring training workouts in Macon, Georgia. The March 31,1894 edition of the Sporting Life noted that Hawke was not leaving his home in Elkton until Oriole manager Ned Hanlon restructured his contract. Bill stubbornly held out until the beginning of May, eventually garnering a substantial raise in salary from Hanlon. In his first game back with the club on May 17, Hawke defeated the Washington Senators 10-2, giving up only three hits.

As the season progressed, Hawke, who battled a sore arm for most of the year, continued to pitch well, going 16-9 while completing 17 of his 25 starts. The Orioles captured their first National League pennant, and Bill finished second in the league with a little under three strikeouts per game.

Discussing Hawke’s outstanding pitching, the Sporting Life of October 6, 1894, noted, “He is what is called a ‘phenom’ and pitches a very swift, puzzling ball, difficult to fathom.”

In an article that appeared in the same edition of the Sporting Life, St. Louis Browns pitcher Ted Breitenstein commented on the toughness of his former teammate: “Hawke of Baltimore has lots of sand. When he was with the Browns, a knot the size of an egg would form near the elbow of his pitching arm after every game. I told him he must quit using his drop ball so often or he would lose his arm. How he stands the pain and suffering which he goes through after every game is a source of wonder to me. You seldom find him in two games in the same week.”

Hawke started Game Four of the Temple Cup Championship5 for Baltimore against the New York Giants in the fall of 1894. The wear and tear on his arm from the regular season possibly contributed to his giving up nine hits and four runs in just four innings. Kid Gleason took over in the fifth inning, and the hot hitting Giants scored 11 more runs on their way to a four-game sweep of the Birds.

Bill notified Oriole team officials in the spring of 1895 that he would not be reporting to the team until he received a raise in his annual salary. Because this had become a yearly ritual, Baltimore’s management was not unduly alarmed. Unfortunately, this time was different as Bill was suffering from a severely broken wrist that occurred when he fell off a horse about a week before he was scheduled to report to the team. Keeping the injury under wraps, he hoped to buy himself some recuperating time by prolonging his contract negotiations. By early June, the Orioles were ready to meet Hawke’s demands, but his wrist still had not healed sufficiently so he had no choice other than to make the Oriole front office aware of his injury.

While attending a game at Union Park in Baltimore on June 19, Bill spoke to reporters about the status of his wrist injury. Hawke told the local press that at the present time he could barely close his hand, but he had been pitching a little bit in the last few days and hoped to come around in a few weeks. Unfortunately for Hawke, the broken bone never did mend correctly. The January 18, 1896, edition of the Sporting Life reported that his wrist was going to be re-broken and set again in order for it to heal properly.

In order to supplement his income, Hawke took on employment at a Wilmington saloon. In late March of 1896, he received a contract offer from Al Lawson, who was managing the Pottsville team. However, Hawke’s slow recovery prevented him from joining the club. A short time later, Bill returned to the game as a substitute umpire in the Atlantic League.

By 1898, Bill was working at a local feed shop and still not pitching. He was also an avid outdoorsman who liked hunting and fishing. In addition, Hawke enjoyed attending and betting on the bantam rooster fights that were held around the Wilmington area. A brief line in the March 16, 1895 Sporting Life noted that Hawke would walk five miles on stilts through a swamp to watch two roosters go at it.

In 1899, Hawke attempted a comeback with the Brockton Shoemakers of the New England League. Bill’s good work in the box for the Shoemakers was noted in the July 29, 1899, edition of the Sporting Life: “Hawke has improved steadily since joining the team, until now he is pitching the best ball of all the pitchers. He is the speediest man in the league. Besides having a wonderful drop ball, he is steady and seldom gives a base on balls.”

Bill seemed to regain his old form, going 11-6 before the ballclub disbanded in early August. A lifetime .230 hitter in the minors, Hawke batted .277 for Brockton with 18 hits and a home run.

After the Shoemakers folded, Hawke signed with the Albany Senators of the New York State League on August 13. The Senators went on to win the pennant, and Bill went 3-2 in 84 innings of work. When the New York State League season ended, Bill finished out the year pitching for an independent team from McClure, Pennsylvania.

Hawke started out the 1900 season with Albany. On June 30, the Sporting Life noted that Hawke and teammate Lem Bailey were suspended from the team6. Bill never gained reinstatement, and his professional baseball career ended at this time7.

Sadly, Bill’s health began to deteriorate rapidly and on December 11, 1902, Hawke passed away at his home from carcinoma8 at the age of 32. His Death Certificate lists his last occupation as Saloon Keeper. The funeral service was held on December 15 at his residence at the corner of Cedar and Brown Streets in Wilmington. Numerous friends and family along with the Wilmington Chapter of the Fraternal Order of Eagles, attended the service. Hawke’s obituary in the Wilmington News shows him as being married, but his wife’s name is not mentioned, nor are any children in the newspaper article or on the death certificate9. He is buried at the Brandywine and Wilmington Cemetery. During his days on the diamond, Hawke was evidently willing to share his knowledge of the game with aspiring ballplayers in the Wilmington area. In 1995, ninety-three years after his death, he was elected to the Delaware High School Baseball Coaches Hall of Fame.

An updated version of this biography appears in SABR’s No-Hitters book (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Wilmington News

Sporting Life

Baltimore American

Baltimore Sun

Wilmington Sunday News

Chestertown Transcript

Special thanks

Frank Russo for providing me with Bill Hawke’s Death Certificate

Marty Payne for providing me with information on Hawke’s career.

Reed Howard for providing me with information on Hawke’s career.

Ben Prestianni, Wilmington Public Library Reference Department

Notes

1 “Morocco” was the term that was given to the process of turning goatskin into shoe leather.

2 A line in the April 5,1894 edition of the Chestertown Transcript noted that Richard (R.V.) Hawke had not yet signed with Baltimore. There are also other numerous instances in various newspaper accounts where Hawke’s first name was given as “Dick,” yet his given name on all documents I located was William Victor Hawke.

3 St. Louis owner Chris Von der Ahe was well known throughout baseball circles for issuing frivolous fines to his players for a variety of minor infractions.

4 In 1892, the overall batting average for National League teams was .245. The following season, when the pitching distance was expanded from fifty-five feet to sixty feet, six inches, team batting averages jumped up to .280. Conversely, the National League cumulative earned run averages went from 3.28 in 1892 to 4.66 in 1893.

5 The Temple Cup was a best-of-seven games post-season series that was played between the first- and second-place teams in the National League from 1894 through 1897.

6 I was unable to locate the reason for Hawke’s suspension from the Albany team in 1900.

7 I found no other mention of Hawke playing professionally, but it is possible he continued to play amateur ball in the Wilmington area.

8 Carcinoma is a subtype of cancer that arises from epithelial cells. The epithelial cells form the linings of the internal organs, cavities, glands and skin.

9 The 1900 U.S. Census lists William V. Hawke as single and living at his father’s residence. Hawke’s marriage took place after the 1900 Census was taken so I was unable to find out his wife’s first name.

Full Name

William Victor Hawke

Born

April 28, 1870 at Elsmere, DE (USA)

Died

December 11, 1902 at Wilmington, DE (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.