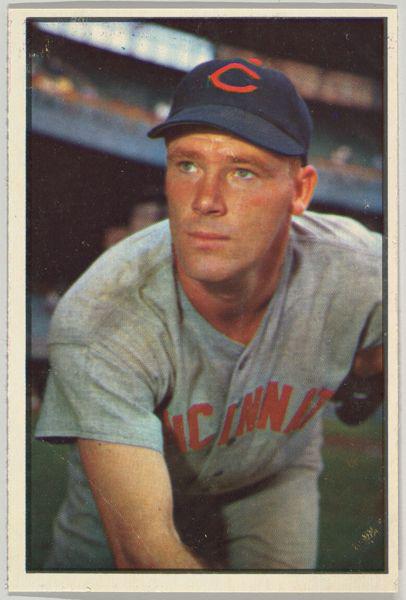

Herm Wehmeier

“Hometown boy makes good” is a classic trope of film, fiction, and sports pages. The dirty-faced boy from the sandlots grows up to be the star of the local nine, the surrogate son or brother, buddy or boyfriend of every fan.

“Hometown boy makes good” is a classic trope of film, fiction, and sports pages. The dirty-faced boy from the sandlots grows up to be the star of the local nine, the surrogate son or brother, buddy or boyfriend of every fan.

When the hometown boy fails to make good — or good enough — the result can be brutal.

Pitcher Herm Wehmeier had the misfortune to sign with the team of his birthplace, the Cincinnati Reds. In six full seasons, the muscular right-hander became “the No. 1 whipping boy for Crosley Field fans.”1

“He was one of the greatest natural athletes we ever had in Cincinnati,” Reds general manager Gabe Paul said. “But never in my long baseball experience have I heard a man booed as bitterly as was Wehmeier. Nothing he could do was right. Even when he won, they booed him.”2

When he was mercifully traded, Wehmeier said, “I like the Cincinnati fans—but they evidently didn’t like me. And no matter how much you try not to hear the boos, they sink through.”3

The storybook ending would have the transplant bloom in his new garden and live happily into a golden old age. This is not a storybook.

Herman Ralph Wehmeier was born in Cincinnati on February 18, 1927, the third child of Edith Mae (Herron) and Herman Wehmeier, an interior decorator who played trumpet in a band. Young Hermie became a star in football and baseball at Western Hills High and won 52 consecutive games while leading the Bentley Post team to the American Legion national championship in 1944. A hard-running fullback at 6-feet-2 and around 190 pounds, he turned down college scholarship offers to choose baseball. “Ever since I was a kid, I had wanted to play with the Reds,” he said.4

In 1945, with major-league clubs desperate for players in the fourth year of World War II, the 18-year-old high school senior went to the major-league spring training camp in Bloomington, Indiana, where the other job seekers included 43-year-old Guy Bush and 46-year-old Hod Lisenbee. The Reds had tried out a 15-year-old, Joe Nuxhall, the previous year. Although Wehmeier stayed only a week during his spring break from classes, manager Bill McKechnie saw enough of his fastball to label him a “surefire star.”5

After graduation in June, Wehmeier joined the Reds’ top farm club at Syracuse. He was called up to make his debut with seventh-place Cincinnati on September 7. Starting the second game of a doubleheader against the Phillies, he walked the leadoff batter and gave up two hits and a run before he retired the side. The second inning was worse, much worse: two doubles, two singles, and two runs before Wehmeier was lifted with two on and nobody out. Reliever Lisenbee let both inherited runners score.

Wehmeier’s second test, a week later against the Giants, looked like more of the same when he gave up a walk and a single to the first two men he faced. But a double play killed the rally, and another double play saved him in the second inning. His luck ran out in the fourth when the Giants scored twice to end the rookie’s season with a 12.60 ERA.

The return of real big leaguers in 1946 sent Wehmeier back to the minors, where he belonged. He stuck with the Reds in 1948 to begin a soul-killing six seasons. The club was bad and he was worse. “He walked out to boos and tried just as hard as he could; too hard,” first baseman Ted Kluszewski recalled. “The more they would boo, the madder he would get, and the harder he would throw. Of course, there went his control.”6

Wehmeier led the National League in walks three times, in wild pitches twice, and in hit batters once. He walked around five per nine innings while with Cincinnati. He couldn’t keep his breaking pitches in the strike zone, so hitters sat on his fastball, and those fastballs left the park at an alarming rate. Although he had the build of a power pitcher, he didn’t have the stuff. He didn’t miss bats, usually striking out only three or four per nine innings.

While the home fans savaged him, Wehmeier was just as bad on the road with an ERA over 5.00 at home and away. Still, the club hung onto him, unwilling to give up on a live arm no matter what the fans thought.

“The trouble with you guys is you all grew up with Hermie,” Pirates manager Fred Haney once told a Cincinnati audience. “You’re jealous because he’s making more money than you are. So you go out to the ballpark and the first time he shows a weakness, you boo.”7

In his best year with Cincinnati in 1951, he posted a 110 ERA+ (100 is average) but a 7-10 record for the sixth-place club. He hit bottom in 1953 when his ERA soared to 7.16 and he gave up 20 home runs in only 81 2/3 innings. The Redlegss parked him in the bullpen to begin the 1954 season. After a pair of strong relief appearances, he got another trial in the starting rotation with ugly results: 13 runs allowed in 18 innings over three starts.

On June 11 Wehmeier relieved in the seventh against Brooklyn to protect a 5-2 lead. He faced eight batters and gave up four runs and the lead. As fans jeered him off the mound, GM Paul got on the phone to his Philadelphia counterpart, Roy Hamey.

“Are you interested in purchasing Wehmeier’s contract?” Paul asked.

“We are.”

“He’s yours. When do you want him to report?”8

The 27-year-old Wehmeier left Cincinnati with a 5.25 lifetime ERA, a 49-69 record, and a battered ego. He had once been one of the league’s most promising young pitchers; Paul said Brooklyn’s Branch Rickey had offered $300,000 for him in 1948. Now the Phillies bought him for a little more than the $10,000 waiver price.

“I still say Wehmeier will win for the Phils,” Paul told a reporter. “It’s a case of sending a player to another team when you know he’s going to help them, but there’s nothing I can do. I’m convinced that Wehmeier would never win for the Redlegs.”9

In a script too far-fetched for Hollywood, his first start for his new team came against his old one when the Redlegs visited Philadelphia. It was a horror movie. In the first inning Wehmeier gave up a walk, a single, a wild pitch, an intentional walk, and a bases-loaded walk. He left the game without retiring a batter.

But he quickly turned his season around with an 11-inning complete-game victory over the Cubs and a shutout of Pittsburgh. Using a slider he learned from new teammate Murry Dickson, he finished 10-8, 3.85 for Philadelphia with improved control and a career-best 1.217 WHIP. He fell back the next year as his ERA rose to 4.41 to go with a 10-12 record.

In May 1956, Philadelphia and St. Louis swapped a bunch of middling pitchers. Wehmeier and Dickson, a 39-year-old former Cardinal, went to St. Louis for Harvey Haddix, a onetime 20-game winner hobbled by a bad knee, Stu Miller, and Ben Flowers. Why the Cardinals wanted him is a mystery; he sported a 0-11 record against them.

He gave St. Louis two years of about league-average pitching as a swing man, starting and relieving. He adopted an elaborate high-kicking windup and developed an effective change-up.

On the next-to-last day of the 1956 season, he faced the Milwaukee Braves, who were tied for first place with Brooklyn. Wehmeier served up a first-inning solo home run to Bill Bruton, but the Cardinals evened the score in the sixth against Milwaukee’s Warren Spahn. The future Hall of Famer and the journeyman dueled into extra innings with Wehmeier shutting out the Braves through the 12th before St. Louis plated the game-winner on doubles by Stan Musial and Rip Repulski. The loss dropped Milwaukee behind the Dodgers, who clinched the pennant the next day.

Manager Fred Hutchinson tapped Wehmeier as the Cards’ Opening Day starter in 1957 in Cincinnati. With his family in the stands, the exile conquered his hometown jitters to hold the Redlegs to eight hits, two of them cheap doubles into the overflow crowd that spilled onto the outfield grass. He came away with a 13-4 victory.

Although he never lived up to his promise, Wehmeier was a different pitcher after he was traded away from Cincinnati. For the rest of his career, he notched a 43-39 record and 4.11 ERA, more than a full run better than he had done for his hometown team.

A sore elbow forced him into premature retirement. After three appearances in 1958, the Cardinals let him go on waivers to the Detroit Tigers. He spent a month on the disabled list and pitched only seven times for Detroit. Offseason surgery provided no cure. “The elbow gets real sore and it swells up,” he said. “I get a tingling in my little finger and the one next to it, and they go numb.”10 When the Tigers released him the next spring, he was finished at age 32.

Wehmeier had married a hometown girl, Mary Sue Satzger, in 1950, and they had four sons and a daughter. He scouted for the Reds while working as an executive in the trucking industry in Cincinnati and Indianapolis. His second son, Jeff, was the Chicago Cubs’ first-round draft choice in 1971, the sixteenth player selected right after the Red Sox took Jim Rice. Jeff, a right-handed pitcher who had recorded five no-hitters at Brebeuf Jesuit Preparatory High School in Indianapolis, played for three seasons in the minors.

The year after Jeff was drafted, Wehmeier moved his family to Texas, where he became district terminal manager for Midland Trans-National Trucking. When a company employee was charged with stealing a shipment of trousers off a truck, Wehmeier was called to testify at the trial in Dallas federal court. While on the witness stand on May 21, 1973, he dropped dead of a heart attack at 46.11

Wehmeier’s rough treatment by Cincinnati fans scared off another Western Hills High graduate and sought-after pitching prospect, Dick Drott. “I didn’t want to pitch in my hometown and have the people get on me like they did on Wehmeier,” Drott said after he signed with the Cubs.12 But yet another Western Hills product, Pete Rose, joined the Reds and became a local hero. Rose said Wehmeier was “the example everyone uses to show it’s hard to play in your hometown.”13

“I didn’t mind the boos for myself,” Wehmeier said. “It’s when my family was at the park that it hurt. But ever since I was a kid, I had wanted to play with the Reds. That’s why I signed with them, and that’s why I’d still sign if I had it all over again.”14

Acknowledgments

Photo credit: Bowman Gum Co. This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 Lou Smith, “Big Klu Gets Rest; Drew Hurls Today,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 19, 1954: 15.

2 “Obituaries,” The Sporting News, June 9, 1973: 40.

3 “Wehmeier, ‘Glad,’ Joins Phillies,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 14, 1954: 23.

4 “Quotes,” The Sporting News, June 10, 1959: 14.

5 “Reds, Bruins Again Today; Big Mac Slams Long Homer,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 9, 1945: 16.

6 Tom Callahan, “No More Boos for Herm,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 23, 1973: 29.

7 Pat Harmon, “Wehmeier Leaves a Mystery,” Cincinnati Post, June 14, 1954, in Wehmeier’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

8 Smith, “Picone Makes Debut for Redlegs Today,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 12, 1954: 58.

9 Earl Lawson, “Phils Buy Hermie as Bums Bombard Him,” Cincinnati Times-Star, June 12, 1954, in HOF file.

10 Harmon, “Wehmeier Released,” Cincinnati Post & Times-Star, May 25, 1957, in HOF file.

11 “Ex-Pitcher Collapses,” Dallas Morning News, May 22, 1973: 4. The judge in the trial was Sarah Hughes, who had administered the oath of office to President Johnson aboard Air Force One after President Kennedy was assassinated.

12 Harmon, “Wehmeier Released.”

13 Callahan.

14 Harmon, “Wehmeier Released.”

Full Name

Herman Ralph Wehmeier

Born

February 18, 1927 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

May 21, 1973 at Dallas, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.