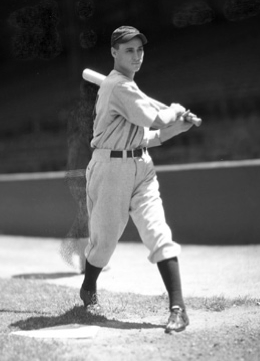

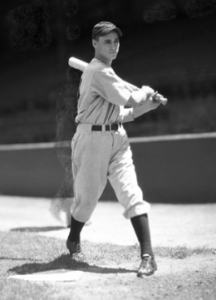

Flea Clifton

The Great Depression is remembered as a time that ruined many a man. People could no longer rely on help from their families, money and shelter were hard to come by, and hunger was commonplace. Long before these hardships started hitting the average man, Herman Clifton had grown to expect hardship as everyday life. In later years Herman sometimes said he would gladly relive the Depression. They were some of the best years of his life.

The Great Depression is remembered as a time that ruined many a man. People could no longer rely on help from their families, money and shelter were hard to come by, and hunger was commonplace. Long before these hardships started hitting the average man, Herman Clifton had grown to expect hardship as everyday life. In later years Herman sometimes said he would gladly relive the Depression. They were some of the best years of his life.

Herman Clifton was born on December 12, 1908, in Cincinnati’s West End, an area that had known hardship both before and after the Great Depression. (During his playing career his year of birth was listed as 1911.) Herman remembered little of his father. He knew he was a tall man, 6-feet-2, and he weighed 175 pounds. His dad left Herman to go fight overseas in the First World War. In 1918 he fought in the Argonne Forest; the Argonne Offensive was the final battle of the Great War that led to Germany’s surrender. It also was the bloodiest battle in the United States’ history. Herman’s father was one of 26,277 Americans who never returned.

At the age of 9, Herman found himself without a father, but his tragedies were far from over. When he was 15, a “friend of the family” had been drinking heavily.1 The man was an acquaintance of Herman’s stepfather and ended up strangling Clifton’s mother with Herman’s own school necktie. The same man eventually killed another woman and was put to death for that murder.

Herman’s stepfather had never got along with his stepson and, in turn, Herman had little respect for the man. It wasn’t long after his mother’s death that Clifton found himself kicked out in the snow. He ended up crossing over into Ludlow, Kentucky, and lived behind a garage that had a potbellied stove. He ate whatever generous locals had to offer; whether they were willing donors didn’t always matter to the young teen.

Through it all, Herman continued to go to school. He loved school and he excelled athletically. It was at this period in his life that he found a direction from reading a book. As Herman would claim, he found his patron saint: Tyrus Raymond Cobb. A book on Ty Cobb became a major influence in his life.

Herman knew that Cobb was much bigger than the slight teen but Clifton’s goal was to match Ty in tenacity. In Herman’s own words, “My philosophy was to attach my wagon to a star.”2 Throughout Clifton’s career he would show a loyalty to “star” players. Whether it was his lifelong defending of Ty Cobb, or praising and supporting Mickey Cochrane or Rogers Hornsby, Clifton showed sincere loyalty to some of baseball’s biggest names. In defense of Hank Greenberg, Clifton once told teammates, “Where the hell would you guys be if it wasn’t for Hank up to this time? Hank has really been putting the bucks in our pockets. Hell, don’t kick the horse you’re going to ride.”3

Cobb has not always been considered the ideal role model, yet Clifton credited him with keeping his life clean and out of trouble. Herman chose not to drink, smoke, chew, chase women, or stay out late as he focused to pursue his goal of becoming a Detroit Tiger like Cobb.

In school he excelled in both football and baseball. With little outside guidance, it was a Ludlow High School teacher who instructed the teen to turn down football scholarships to Dayton, Iowa, and Purdue to pursue his dream of becoming a Detroit Tiger. Clifton claimed to have attended the “College of Hard Knocks” but others claim he played baseball for the University of Cincinnati.4 Regardless, he played sandlot and semipro baseball throughout Cincinnati and played shortstop for Cincinnati Pleasant Ride, a local team that won the 1929 National Baseball Federation championship. At the tournament, just months before the stock market crash that helped launch the Great Depression, Clifton’s life suddenly took an upswing.

Billy Doyle had a notable career as a longtime scout. He discovered or signed such players as future Hall of Famers Rick Ferrell, Hank Greenberg, Branch Rickey, George Sisler, and Billy Southworth, as well as notables like Tommy Bridges, Floyd Giebell, Hank Gowdy, Ray Hayworth, Sam Jones, Dickie Kerr, and dozens of other major leaguers. Yet in 1929, then a Tigers scout, Doyle must have thought he was dreaming when the all-tourney shortstop told him his ambition was to become a Detroit Tiger. Cobb himself might have questioned Clifton’s turning down more money from the St. Louis Cardinals, but to Clifton the decision was simple. He signed with Ty Cobb’s Tigers.

Clifton’s first stop was the Raleigh Capitals in the Piedmont League. It was there he met a fellow first-year professional named Hank Greenberg. Raleigh’s field was built on an old brickyard. The young shortstop committed 44 errors on the challenging field but still led the league’s shortstops in fielding. The following season in Raleigh was spent without Greenberg, who was already moving up. Still the Capitals saw a marked improvement, jumping from fifth place to second. Clifton’s batting average climbed to .301, good enough to find himself rejoined with Greenberg, this time in Beaumont, Texas.

The Beaumont Exporters gave Clifton a taste of what the big leagues would be like. The vast majority of the Exporters ended up with major-league experience and it showed as they won both the Texas League regular season and the championship series. Clifton played well in Beaumont, switching to second base in his second season in Texas. Once again he hit .301 and he added a Cobb-like 49 stolen bases to his 1932 totals.

The Exporters would also give Clifton the nickname that would be his moniker for the rest of his life. After a knee injury Clifton tried relentlessly to convince his manager, Del Baker, that he was fit to play. Baker finally responded that the annoying Clifton was worse than a sand flea. The days of “Herman” were over.

One assessment of Clifton’s skills stated, “Flea is a fightin’ man —Reports are that he has flattened many a foe who towered a foot above him.”5 An exaggeration for sure, but probably more because Clifton could not find a 6-foot-10 player to tangle with. In the minors he did enjoy a good scrape even if it was his own teammate —the 6-foot-4 Hank Greenberg. Not that fighting over who gets to practice first isn’t a worthy cause, but as Greenberg found out, it didn’t take much to set Flea off. Greenberg remembered another episode with Clifton’s bat: “Flea guarded that bat with his life: he’d fight anybody that came near it. He was a tough little guy, even though he weighed only about 150 pounds. On the road, he used to eat nothing but doughnuts and bananas. He said they were cheap and filling and they stretched his meal money. Flea was the only ballplayer who could show a profit on $1-a-day meal money.”6 To be sure, Ty Cobb always appreciated a fightin’ but frugal man.

In 1934 Clifton was finally called up to play with Detroit. “It wasn’t a very enviable position,” he recalled.7 In 1934 the Tigers had one of the greatest infields ever. Marv Owen and Billy Rogell handled third and short, and the right side of the infield was manned by future Hall of Famers Charlie Gehringer at second and Greenberg at first. Nicknamed “The Battalion of Death,” the 1934 Tigers infield still (as of 2014) holds the record for the most RBIs by a unit, 462. Clifton remembered, “There wasn’t anybody that’d have a chance to break in on that infield. But I practiced every day just like I was gonna play in every game.”8 He was aware that his chances of playing would be better outside of Detroit, but that was never the plan. With no regrets, Clifton reminisced, “Mickey [Cochrane] knew that. He knew that I would be playing second base for about four or five teams in that league, but they weren’t about to tell me at that time. I understood this, but that was my ambition —to play ball with Detroit and I was going to make the best of it.”9

Clifton was a utility infielder from 1934 to 1937. All of his time in the majors was with Detroit. He played in only 87 games over the four-year span, never hit a home run, and was a lifetime .200 hitter. His big year was 1935, when he started 30 games in the infield, usually for Owen at third base but occasionally spelling Gehringer or Clifton’s roommate Rogell. Three times he had three hits in a game, all in 1935. Clifton collected five hits in a doubleheader against the Yankees in which Lefty Gomez pitched the first game. Late in the season, against Washington, he led both teams with three hits and two runs in a 5-4 Tigers win.

Overall, Clifton had more of an “I’m just glad to be here” type of career. His favorite play was a Cobb-like moment he had in 1934 against the Washington Senators. He came in as a pinch-runner in the eighth inning. Tiger Jo-Jo White chopped one to second and Flea was off to the races. As the second baseman flipped the ball over to first to get the speedy White, Clifton was already rounding third and blowing through third-base coach Del Baker’s stop sign. By the time the relay came home, Clifton was already sliding in safely. Manager Mickey Cochrane greeted the daredevil in the dugout with a congratulatory pat and said something similar to, “You know, son, if you wouldn’t have scored I would have shipped your ass so far away it’d cost you $75 to send me a postcard to let me know where you were.”10 But, for that moment, Cobb and Clifton were one.

Clifton did not appear in the 1934 World Series. However, in baseball lore he will always be linked to Hank Greenberg and the 1935 Series. In Game Two Greenberg broke his wrist sliding into home. The devastated Tigers scrambled for a plan to try to replace their top offensive weapon for Game Three. Pitcher Schoolboy Rowe (Clifton’s roommate in Beaumont) volunteered to play first base. Manager Cochrane contemplated putting himself at first and letting Ray Hayworth catch. The Tigers rotated four outfielders on a regular basis. Maybe one of them could play first. Even Clifton was caught by Greenberg testing out Greenberg’s own glove just in case Clifton would be the fill-in at first. But it would be Tigers owner Frank Navin who made the decision. He ordered Cochrane to move third baseman Marv Owen over to first. The kicker was that Navin wanted Clifton to start the remaining games at third base.

For four games, Flea Clifton was a starter in the World Series. By the second inning of his first game, he had already committed an error. At the plate it was even worse: 0-for-16 in the four games that would define his career. But it didn’t matter. After those four games he would be known as “Flea” Clifton, 1935 World Series champion. Even Ty Cobb could never claim world-champion status.

Clifton never did like the scorer’s decision to give him what ended up being his only error as the Tigers won Game Three, 6-5. In Game Four he scored what proved to be the winning run in a 2-1 game after reaching second on an error, though he believed to the day he died that he had hit a double. He did draw a pair of walks in the Series, and even batted leadoff in the deciding game, but he was probably best known for his nonstop banter with the Cubs players and coaches. Ty Cobb would have been proud.

Over the next two years, Clifton played in just 28 more games in the majors. By the middle of 1937 he was back to the minor leagues for good. He went from Toledo to Toronto to Oklahoma City to Fort Worth before finally ending up in Minneapolis in 1943. Clifton had a good year in ’43. He considered managing the team in 1944 or even trying for a major-league comeback with so many younger players off fighting in World War II. But he was tired of traveling. He missed his wife, Marcella, and their kids. He missed Cincinnati. It was time to move on.

Flea Clifton became an insurance salesman, retiring a second time 40 years later as a vice president of George R. Hammerlein Insurance. The hours worked well with coaching baseball, being a Shriner, gardening, and always graciously signing autographs. He continued to encourage others to read about Ty Cobb and ironically, stressed “manners first” to his teams that won several local as well as national championships.

In 1997 Flea Clifton was interviewed along with Billy Rogell for a documentary about Hank Greenberg, The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg. It was critically well received but Clifton never saw it. On December 22, 1997, he died from a stroke before the documentary was released in 1998. He was survived by Marcella, his Cincinnatian wife of 66 years, their three daughters, Arlene Nixon, Carol Couch, and Gwenn Smith, and their son, Kerry Clifton. He also had 15 grandchildren, and 15 great-grandchildren. He was buried in his coaching uniform in Bridgetown, Ohio, overlooking the local baseball field. The same Cincinnati Enquirer that had written a headline 62 years earlier calling Flea “Cincinnati Hero of Series” now wrote an obituary titled “Clifton Hero of ’35 World Series,” leaving Ty a little envious.

Sources

Bevis, Charles, Mickey Cochrane: The Life of a Baseball Hall of Fame Catcher (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1998).

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Second Edition (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 1997).

Lieb, Frederick, The Detroit Tigers (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1946).

Rosengren, John, Hank Greenberg: The Hero of Heroes (New York: New American Library, 2013).

Skipper, John C., Charlie Gehringer: A Biography of a Hall of Fame Tigers Second Baseman (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008).

Smith, Fred T., Tiger Tales and Trivia (Lathrup Village, Michigan: Fred Smith, 1988).

Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Flea Clifton

Baseball-reference.com

Notes

1 Richard Bak, Cobb Would Have Caught It: The Golden Age of Baseball in Detroit (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1991). 243.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Brent Kelley, “Flea Clifton; Lifelong Disciple of Ty Cobb,” Sports Collectors Digest, July 15, 1994.

5 Russ Murphy Tiger Tales. (Your Plymouth Dealer, pamphlet, Detroit, 1934).

6 Ira Berkow, Hank Greenberg: The Story of My Life (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee Books, 2009), 23.

7 Kelley, 137

8 Kelley, 137.

9 Kelley, 137

10 Bak, 249.

Full Name

Herman Earl Clifton

Born

December 12, 1908 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

December 22, 1997 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.