Frank McQuade

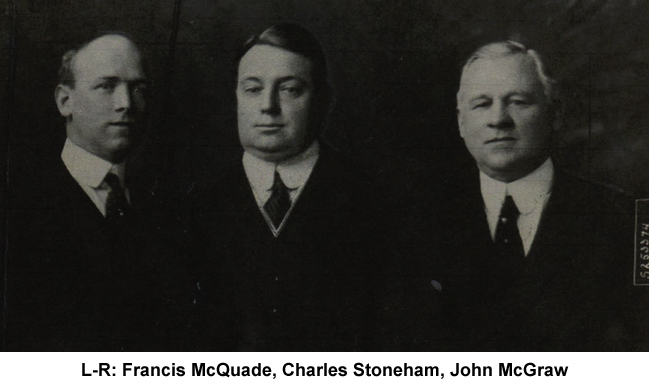

Although forgotten today, Frank McQuade was a figure well-known to New Yorkers of the Jazz Age. Among other things, McQuade was a highly visible Manhattan magistrate, an influential Tammany Hall operative, and widely regarded as “the father of Sunday baseball in New York.”1 He was also a peripheral target and/or government witness in various municipal corruption investigations. But the lion’s share of the considerable newsprint that McQuade garnered during his lifetime was generated by his stormy tenure as minority owner and club treasurer of the New York Giants. In May 1928 his ouster from the treasurer’s post by principal club owner Charles Stoneham touched off years of litigation, with often tawdry in-court revelations leaving McQuade, Stoneham, and Giants manager John McGraw considerably diminished in public esteem. In the end, McQuade lost his lawsuit against the Giants and spent the final two decades of his long life mostly out of the limelight.

Although forgotten today, Frank McQuade was a figure well-known to New Yorkers of the Jazz Age. Among other things, McQuade was a highly visible Manhattan magistrate, an influential Tammany Hall operative, and widely regarded as “the father of Sunday baseball in New York.”1 He was also a peripheral target and/or government witness in various municipal corruption investigations. But the lion’s share of the considerable newsprint that McQuade garnered during his lifetime was generated by his stormy tenure as minority owner and club treasurer of the New York Giants. In May 1928 his ouster from the treasurer’s post by principal club owner Charles Stoneham touched off years of litigation, with often tawdry in-court revelations leaving McQuade, Stoneham, and Giants manager John McGraw considerably diminished in public esteem. In the end, McQuade lost his lawsuit against the Giants and spent the final two decades of his long life mostly out of the limelight.

Francis Xavier McQuade was born on Staten Island on August 11, 1878, one of 12 children born to Irish-Catholic immigrant Arthur J. McQuade (1845-1909) and his wife, Ellen (née Tuite, 1850-1928), a native of New York.2 Brought to America with family as a child, the adult Arthur became well-to-do running the unchic but lucrative Manhattan rag and junk business started by his father, Thomas McQuade. As a result, Arthur’s children were raised in comfort. But not without the embarrassment attending their father’s arrest and imprisonment in the late 1880s.

Like others with ambition, Arthur McQuade joined Tammany Hall, the corrupt political organization that controlled the Democratic Party in Manhattan and soon proved himself a capable man. Elected as a Tammany candidate to the New York City Board of Aldermen in 1883,3 Arthur was one of 13 “boodlers” subsequently indicted for accepting bribes in connection with a railway franchise scheme. After his first trial ended in a hung jury, McQuade was convicted on retrial and sentenced to seven years’ hard labor at Sing Sing Prison. He had been incarcerated for 21 months when his conviction was vacated and a new trial ordered by the New York Court of Appeals.4 And when the prosecution fell apart on the do-over, McQuade was acquitted. His political aspirations irretrievably lost but again at liberty, Arthur refocused his attention on the family business and prospered, leaving an estate valued at over $200,000 when he died in 1909.5

The continued affluence of the family afforded Frank McQuade a first-class education that culminated in graduation from New York University Law School in 1900. Thereafter, he secured employment in city government as an assistant corporation counsel. In May 1906 he married Lucille Khrone and soon began the family that would eventually include son Arthur (born 1908) and daughters Helen (1911) and Lucille (1919). A protégé of Tammany powerhouse Big Tim Sullivan, McQuade was appointed a magistrate of the New York City Court in 1911. He was only 32, and would remain on the bench for the next 19 years.6

Although the McQuade clan had its share of athletes – uncle Barney (Bernard) McQuade had been a world-class handball player in the 1880s and cousin Jim McQuade was an outstanding World War I-era pitcher at Fordham College – the playing of sports is conspicuously absent from the resume of Frank McQuade.7 Still, McQuade, like many Tammany members, was a close follower of major-league baseball and an ardent fan of the New York Giants.8 Given that, and a shared fondness for alcohol, racetracks, and Manhattan nightlife, it was only a matter of time before McQuade and Giants manager John McGraw found each other. Another thing that the two had in common was a predilection for using their fists, particularly after heavy drinking. But unlike the small-but-pugnacious McGraw (who took his lumps more often than not in fights), the unimposing Frank McQuade, 5-feet-8, slightly built, and prematurely bald, was a fearsome brawler and a man to be avoided in a melee. Much alike, the two feisty Irishmen quickly became fast friends.

Whether typical of the times or a personal failing, Judge McQuade was not always sensitive to the ethical ramifications of matters that came into his court. Nor did he necessarily feel constrained to uphold the law that he was oath-bound to enforce. This was exemplified in the case that first brought him widespread public notice. Notwithstanding an express statutory prohibition against playing professional baseball games in New York on Sunday,9 McGraw’s Giants and manager Christy Mathewson’s Cincinnati Reds scheduled a Sunday game at the Polo Grounds in August 1917, with all game proceeds earmarked for World War charities. Predictably, the game was brought to a quick halt by New York City police officers, with the two managers cited for violating Sunday blue laws. Despite his personal friendship with defendant McGraw, Judge McQuade saw no need to recuse himself and refer the case to a disinterested jurist. Rather, he retained jurisdiction over the proceedings. Then, reading elements (like a showing that the repose or religious liberty of the community had to have been disturbed by the ball game) into the statute where none existed, McQuade effectively nullified the law. Indeed, the court declared, the accused were to be commended “for lending their services to the patriotic cause” that was to benefit from the activity.10 Thereafter, McQuade basked in the approbation of Baseball Magazine and other result-approving observers.11

In the months that followed and notwithstanding separation-of-powers niceties, Judge McQuade dove into the legislative arena, openly and actively campaigning for the repeal of the law prohibiting Sunday baseball. He spoke out forcefully to the press whenever the opportunity presented itself. He lobbied state senators and representatives in Albany.12 He even enlisted the support of ex-President (and former New York City Police Commissioner) Theodore Roosevelt.13 All to good effect. On April 19, 1919, a bill sponsored by State Senator (later New York Mayor) James J. Walker sanctioning Sunday baseball was signed into law by Governor Al Smith, both Tammany pals of McQuade. Overnight, telegrams of congratulations by the hundreds were dispatched to McQuade, while newspapers nationwide described the adoption of the Sunday baseball bill as “a great personal triumph” for him.14 Three weeks later, a throng of more than 35,000 was on hand at the Polo Grounds to see McQuade throw the ceremonial first pitch in the inaugural Sunday major-league game played in New York (which, unfortunately for the home side, the Giants lost to Philadelphia, 4-3). Finally, on May 24, 1919, more than 1,000 friends and admirers attended a testimonial dinner at the Commodore Hotel in Manhattan to honor McQuade for his efforts on behalf of Sunday baseball. The toastmaster, New York State Supreme Court Justice Victor J. Dowling, extolled the new law, calling its passage “a long step forward in the furtherance of personal liberty in this city.”15 McQuade was then presented with a diamond ring and the pen that Governor Smith had used to sign the Sunday baseball bill into law.16 All things considered, it may well have been the happiest evening of Frank McQuade’s life.

By the time of the glorious occasion at the Commodore, McQuade was more than just an avid baseball fan. He was a club owner, having acquired a small stake in the Giants franchise in January. The events that brought McQuade into club-owner ranks are somewhat murky, with reconstruction of the matter shrouded by the passage of time, inconsistent remembrance, and the sheer number of parties who held shares of franchise stock. Team ownership had been fragmented ever since the Players League conflict had forced club founder John B. Day to sell off parts of his Giants stock to stay afloat during the 1890 season. By 1918 a majority of club stock was owned by the female heirs (second wife and two daughters) of the late John T. Brush, but held in trust by Brush son-in-law and Giants club president Harry Hempstead. Ashley Lloyd, club secretary and longtime baseball junior partner of the Brush family, also held a sizable portion of Giants stock, as did elderly Arthur Soden, the former Boston Beaneaters president who had come to Day’s rescue in 1890. Meanwhile, there were always random lots of Giants stock unaccounted for. As observed by sportswriter Bob Considine decades later, “The Giants have no control over small sales of the club’s stock. A limited number of shares may change hands each year over the counter of a Wall Street brokerage, without knowledge of the team’s board of directors. Giant stock is about as hard to buy as a bar of soap, provided you have the inclination and 150 bucks.”17

In late 1918 McGraw was advised that the Brush heirs wanted to get out of baseball, and quietly set about looking for a buyer. But prospective purchaser George Loft, a millionaire candy manufacturer, soured on acquiring the Giants upon learning that 100 percent of the club stock was not available.18 Sometime thereafter, McQuade, New York Press editor-publisher E. Phocian Howard, or retired NYPD Captain William F. Peabody – accounts vary – introduced McGraw to Charles Stoneham, a wealthy, if unscrupulous, Manhattan stock trader and longtime Giants fan. In short order, a deal was arranged. But complexities resided on both sides. Regarding the sellers, Hempstead’s wife, the private but tough-minded Eleanor Brush Hempstead, refused to part with her shares in the club. Nor would Brush partner Lloyd sell his stock. But combining his own interest in the club with those of widow Elsie Brush and her daughter Natalie, Hempstead nevertheless managed to cobble together a controlling majority of Giants stock. The Hempstead asking price: somewhere between $1 million and $1.3 million.19

Buyer Stoneham had the necessary cash, but for reasons unknown did not simply buy the Hempstead-controlled stock himself. Instead, he formed a three-man syndicate, with himself as kingpin. Enlisted as minority syndicate partners were Giants manager John McGraw and Judge Francis X. McQuade. Under the new regime, Stoneham assumed the post of club president, while McGraw became club vice president and McQuade the new treasurer.20 Court records later revealed that Stoneham personally controlled 1,306 shares, a majority of club stock. Junior syndicate partners McGraw and McQuade each owned 70 shares, lots purchased from Stoneham at the price of $50,338.10 (sums that Stoneham had lent to both McGraw and McQuade for that purpose. Interestingly, the McGraw loan was interest-free; McQuade had to repay Stoneham at a 5 percent interest rate.)21

The elevation of McGraw to club executive rank was a shrewd move by Stoneham. It guaranteed that baseball’s most astute manager would remain in the Giants dugout indefinitely, while simultaneously gratifying a long-held McGraw ambition to move into the club’s front office. But what prompted Stoneham to embrace McQuade, apart from perhaps shoring up support on the political front, is indiscernible, particularly given that civil servant McQuade was not a rich man and required a loan from Stoneham to finance his purchase of club stock. Joining the Giants syndicate and accepting the $7,500-a-year salary paid the club treasurer also required McQuade to disregard the strictures of a New York judiciary statute that expressly prohibited a city magistrate from engaging in any other paid occupation or profession.22 He would act as a city court judge and New York Giants corporate official simultaneously – a course that would go unchallenged for a decade but ultimately cost McQuade dearly.

In the short run, the syndicate arrangement worked to everyone’s satisfaction. Stoneham reaped the benefits of a revitalized franchise, successful on the field while setting new league attendance records. With unfettered access to the ample Stoneham checkbook, McGraw rebuilt the Giants into the winner of four consecutive NL pennants (1921 to 1924) and captured World Series crowns the first two years. But perhaps happiest of all was Frank McQuade, who reveled in his association with the club. He invariably accompanied the players to spring training, cavorted merrily both on and off the field, and, unexpectedly, developed into a club spokesman, a task that Stoneham, for all his notoriety,23 preferred to avoid, and one for which manager McGraw often had no time.

There were many causes for the internal strife that came to plague the ownership syndicate, but the most serious one surfaced early: press speculation that Stoneham was looking to unload his interest in the Giants. Such reports invariably upset McGraw and McQuade because (1) they viewed the syndicate agreement as precluding any member (i.e, Stoneham) from selling his stock in the Giants without the preapproval of the other two (McGraw and McQuade), and/or (2) they believed that a right of first refusal had to be extended to the other syndicate members before a selling syndicator could begin negotiations with a third party for the purchase of his club holdings. The issue first came to public notice following published reports that Stoneham was entertaining sellout proposals made on behalf of ex-Giants president Harry Hempstead, who had come to regret his withdrawal from baseball.24 McGraw and McQuade raged at such reports and threatened legal action. Dissembling by Stoneham only enflamed the situation, soon prompting the portly club boss to retreat to Havana until the furor subsided.25 In time, tensions among the three abated, but the situation would recur time and again over the next decade.26

In September 1923 a far graver crisis confronted the club leadership: Stoneham’s indictment by a federal grand jury on fraud charges related to his stock-trading ventures. After a trial marred by acrimonious exchanges between the trial judge and prosecutors and allegations of jury tampering, Stoneham was acquitted. But ensuing civil suits by defrauded investors against the accused and the legal expenses incurred from continually needing to defend himself strained Stoneham’s finances, and put the brakes on the free spending that had allowed McGraw to build a championship team in the early years of the Giants syndicate. The change in club financial fortunes agreed with neither McGraw nor McQuade, and added to the growing animosity among the syndicate principals.

Court proceedings in late 1931 would expose details of a long-fractious relationship involving the club owners. But prior to that, the only front-office disharmony that received much contemporaneous press attention was McQuade’s criticism of the January 1928 deal that sent Hall of Fame-bound Rogers Hornsby to the Boston Braves in exchange for two pedestrian players, catcher Shanty Hogan and outfielder Jimmy Welsh. It was widely rumored that the gruff and tactless Hornsby had been banished for insulting Stoneham in a hotel lobby after a tough Giants loss. The one-sided deal was entirely Stoneham’s doing, and McGraw, who evidently had no foreknowledge of or input into the trade, kept a prudent public silence in the face of the panning given the transaction by McQuade and the New York press corps.27

At the annual club reorganization meeting months later, the directors of the National Exhibition Company, the Giants corporate alter ego, caught followers of New York baseball off-guard by ousting McQuade from his long-held post of club treasurer. Installed in his stead was Leo J. Bondy, Stoneham’s personal attorney. A formal statement issued by the board declared that the change at the club treasurer position had been made “in order to create greater harmony between the business management and the playing management of the New York National League club.”28 To no great surprise, McQuade did not take his ouster magnanimously. He blasted Stoneham, the obvious architect of his removal, asserting that the club boss had “shown no regard for the rights of minority stockholders, including myself.” He then added, ominously: “In the near future, by appropriate court action, the public will learn much more about Mr. Stoneham’s methods.”29

In the forthcoming battle with his syndicate partners, McQuade soon had an important ally. Sometime during the summer, New York construction magnate (and Tammany Hall buddy) William F. Kenny acquired the Giants stock held by the estate of the now-deceased Arthur Soden, becoming the club’s second largest individual share owner.30 Months thereafter, Kenny instituted litigation on behalf of minority Giants shareholders seeking an accounting of some $410,000 in club funds disbursed to Stoneham from 1919 to 1926. The Kenny action was widely seen as having been instigated by McQuade,31 and Stoneham responded with a lawsuit of his own, seeking $250,000 damages from McQuade for damaging the business reputation of the Giants corporation, disclosure of club secrets, harassment of club employees, and assault, the latter charge being grounded in a punch by McQuade that shattered the eyeglasses of Leo Bondy.32 McQuade was hardly cowed, immediately filing an affidavit that detailed a plethora of dubious club disbursements to Stoneham, some of which were then passed along to McGraw.33 Stoneham did not deny receiving the money, but insisted that the club treasury had long since been repaid, with interest.

But it was the third and final intra-syndicate lawsuit that inflicted the real damage to the Stoneham, McGraw, and McQuade reputations.34 Filed by McQuade in early January 1930, the action sought restoration of McQuade to the post of club treasurer and damages for his unlawful ouster from that post almost two years earlier. But before the suit could be tried, plaintiff McQuade found himself in hot water with the Bar Association of the City of New York, courtesy of perennial Socialist Party office seeker Norman Thomas. On the basis of a Thomas complaint, McQuade would be obliged to reconcile his years of employment and compensation as New York Giants club treasurer with the statute that prohibited a sitting city judge from holding any other paying job.35

From there, things only got worse for Frank McQuade. Soon, the Seabury Investigations Committee, the Tammany scourge that would later drive Mayor Walker from office and effect the dismissal of numerous New York City magistrates, began inquiring into McQuade’s conduct. Committee investigators found no corruption, but nonetheless recommended McQuade’s removal from the bench “for personal conduct and business and other activities which demonstrate his unfitness to continue to serve as a city magistrate.”36 On the morning set for McQuade to appear before the committee, he resigned from the bench, his formal letter of resignation declaring that he had come “to the conclusion that it was illegal for him to serve as a city magistrate and at the same time serve as an officer of the New York baseball club.”37 McQuade also deemed resignation necessary to protect his interest in the Giants, as he did not want to see Stoneham and McGraw escape liability from the still-pending McQuade lawsuit “on a technicality.”38 For its part, the committee saw no need for further proceedings against McQuade and promptly moved on to bigger fish.

After preliminary skirmishing, McQuade’s lawsuit finally came to trial before Justice Philip J. McCook of the New York State Supreme Court in December 1931.39 The linchpin of the action was a proviso in the original syndicate agreement that required Stoneham, McGraw, and McQuade to “use their best efforts for the purpose of continuing [each other] as officers” of the Giants club. Obviously, McQuade asserted, his ouster as club treasurer by board directors appointed and serving entirely at Stoneham’s pleasure [or “Stoneham dummies,” as McQuade called them] contravened that proviso.

While the outcome of the case turned on a point of contract law, the in-court proceedings largely degenerated into a mudslinging contest, with both McGraw and McQuade taking heavy hits (while Stoneham, whose personal reputation by 1931 was probably beyond further calumny, got off more lightly).40 Among other things, McQuade was accused of overuse of Polo Grounds passes for his political cronies; scalping World Series tickets; harassing front-office personnel, particularly the women; drunken escapades during Giants spring camp; threatening Stoneham with violence, and being generally impossible to work with. But the most titillating McQuade indiscretion was one disclosed by erstwhile friend McGraw, who maintained that Frank had slugged Mrs. McQuade when she lost their hotel room key one evening during 1922 spring training in New Orleans. Called to the stand subsequently, Lucille McQuade, by now estranged from her husband, denied the allegation. Besides, asked Lucille, how would McGraw know? He had drunk himself into semiconsciousness and been put to bed well before the alleged incident occurred.41 In his closing argument, Isaac Jacobson, McQuade’s hard-nosed attorney, characterized the warring trio aptly: “None of the men involved is an angel. They are all drinking men, all cursing men, all fighting men.”42

While baseball fans gorged on reportage of the unseemly antics of the three Giants owners, Justice McCook concentrated on the requirements of the syndicate agreement. And here, the court agreed with McQuade. Stoneham and McGraw, both of whom had abstained from the vote to oust McQuade as club treasurer, had breached an agreement-specified duty to assist McQuade in retaining his club officer post. To rectify the injury, a $42,827 judgment was entered in McQuade’s favor. And while the court would not reinstate McQuade as club treasurer over the objection of the other two syndicate members, McQuade was authorized to reinstitute legal action in future if the club failed to reinstate him voluntarily.43

Much to McQuade’s delight, the McCook decision was sustained on review by New York’s Appellate Division.44 The judgment, however, would not become final and collectible until endorsed by the state’s highest tribunal, the New York Court of Appeals. In the meantime, McQuade needed an income. In November 1933 this was arranged by Tammany friends who quietly slipped him onto the city payroll as an assistant in the office of corporation counsel. After a month on the job, McQuade put in his retirement papers.45 Government reform groups, and later the incoming LaGuardia administration, took action to prevent McQuade from receiving a city pension, initiating litigation that left the matter unresolved for months.46

By this time, John McGraw was also in retirement, having stepped down as Giants skipper midway in the 1932 season. Some 18 months later, McGraw lay in a Westchester County hospital suite awaiting terminal stomach cancer to do its worst. A day after being given the last rites, the rapidly failing McGraw received an unexpected visitor: Frank McQuade. “Hello, Judge,” saluted the patient weakly as McQuade entered the room and sat down beside McGraw for a final chat.47 A week after the deathbed reconciliation of the two, McQuade was among the throng in attendance at St. Patrick’s Cathedral for the Requiem Mass for his old friend, dead at age 64.48 McQuade would never reconcile with Giants boss Charles Stoneham (but nevertheless sold his Giants stock to Stoneham sometime after their court battle finally ended).49

By the time of McGraw’s death, Frank McQuade had suffered a punishing financial blow: the loss of his judgment against the New York Giants. In January 1934 the New York Court of Appeals reversed the lower-court decisions and vacated the $42,827 award granted McQuade at trial.50 In the court’s view, any agreement that compelled the directors of a publicly traded corporation to retain an officer deemed unfit for his office was contrary to public policy and unenforceable.51 Additionally, McQuade’s service as Giants club treasurer at the same time that he was a sitting city court judge had been forbidden by statute and rendered the syndicate agreement a legal nullity.52 The following year brought a happier courtroom occasion for McQuade. Following a one-day trial in Supreme Court, a Manhattan jury took all of five minutes deliberation to rule in McQuade’s favor in his pension fight with the city. For the remainder of his days, Frank would be the recipient of a $5,275 annual stipend.53

The quietude of McQuade’s final decades was punctured by two high-profile appearances before investigative bodies probing municipal corruption. In June 1938 McQuade was summoned to appear before a grand jury probing the finances of New York State Senator James A. Hines, a longtime Tammany bigwig and friend of McQuade’s who, despite modest visible sources of income, had managed to acquire Giants stock worth about $70,000.54 What light, if any, McQuade shed on the matter is unknown (but Hines was later convicted of racketeering-related charges and sent to prison). McQuade was back in the public spotlight one last time in January 1953, testifying before the State Crime Commission about an ancient shakedown of boxing promoter Tex Rickard by waterfront powerbroker William McCormick, a commission target. “Now 74, a little old man with a white fringe around his bald head,” McQuade had to be helped to the witness stand, but once there gave a “loud and clear” account of how he had compelled McCormick to surrender the $81,500 prefight tribute that McCormick had extracted from Rickard prior to the storied Jack Dempsey-Luis Firpo heavyweight title bout at the Polo Grounds in 1922.55

In failing health during his last years, Frank McQuade died at his home in Manhattan on April 6, 1955. He was 78. Following funeral services, his remains were interred in Calvary Cemetery in Queens, New York. Survivors included his long-estranged wife, Lucille (to whom the deceased left a bequest of $1),56 his son, Arthur, and daughters, Helen Egan and Lucille Muir.

Sources

The biographical data provided herein has been culled from US Censuses, McQuade family info posted on Ancestry.com, and certain of the newspaper articles cited below. Information about the political and baseball life of Frank McQuade has been taken from contemporary reportage, particularly that of the New York Times.

Notes

1 So described in the opening line of his obituary in the New York Times, April 7, 1955, and elsewhere.

2 The other McQuade children were Mary Ann (born 1871), Ellen (1872), Thomas (1874), Elizabeth (Bessie, 1875), Arthur (1876), Sarah (1877), Benjamin and John (1880), Raymond (1881), Philip (1882), and Harold (Harry, 1886). Four of the McQuade children, however, did not survive infancy.

3 Note that prior to 1898, New York City consisted only of Manhattan and adjoining parts of the West Bronx.

4 Relief was granted Arthur on the basis of a rather strained, hypertechnical reading of the New York jury impaneling statute. See People v. McQuade, 110 N.Y. 284 (1888). The McQuade decision was poorly received by judicial observers and denounced on many newspaper editorial pages. See, e.g., the Boston Advertiser, October 5, 1888, Chicago Tribune, October 6, 1888, New York Herald, October 12, 1888, and San Francisco Chronicle, October 14, 1888.

5 The last will and testament of Arthur J. McQuade, with September 28, 1908, codicil, is viewable on line via Ancestry.com. Frank was left a $20,000 bequest by his father.

6 First tabbed to fill a vacancy in 1911 and thereafter appointed to a full 10-year term by Major William J. Gaynor in 1912, McQuade was reappointed to a second 10-year tem by Mayor John F. Hylan in July 1921. Perhaps needless to say, both Gaynor and Hylan were Tammany stalwarts.

7 The only reference discovered by the writer to Frank McQuade ever playing any kind of ball is contained in a thank-you letter from an ailing Christy Mathewson that stated: “Little did I suspect, when you were my catcher down in Marlin (the Giants spring training spot) years ago, that one day you, as a big league magnate would be voting to have your club give me a testimonial game.” See Letter of Mathewson to Francis X. McQuade, dated December 13, 1921, on file at the Giamatti Research Center in Cooperstown.

8 Although New York Highlanders/Yankees owners Frank Farrell and Bill Devery (and later Jacob Ruppert) were Tammany heavyweights, Sachem men tended to be fans of the Giants, the club founded by Tammany Brave John B. Day back in 1883.

9 New York blue laws banning the playing of sports, selling alcohol, and the like had been on the books continuously since 1695.

10 As reported in the New York Times, Tampa Tribune, and Washington Evening Star, August 22, 1917.

11 See Editorial Comment, Baseball Magazine, Vol. 19, No. 6 (September 1917). Because constitutional protections against double jeopardy prohibit government appeal of a wrongful acquittal, the McQuade ruling was insulated from review and reversal by an appellate court.

12 As reported in the Washington Evening Star, January 29, 1918, Philadelphia Inquirer, December 5, 1918, and elsewhere.

13 As per the Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, April 8, 1918.

14 See, e.g., the Flint (Michigan) Journal, April 26, 1919, Lexington (Kentucky) Herald, April 27, 1919, (Cheyenne) Wyoming State Tribune, April 30, 1919, and (Baton Rouge) State Times Advocate, May 12, 1919. Almost all of these news articles featured a photo of McQuade, as well.

15 As per the New York Times, May 25, 1919. Scheduled to speak, Governor Smith was obliged to send his regrets, but Senator Walker, Tammany boss Charles F. Murphy, and Giants manager McGraw were among the dignitaries in attendance at the McQuade testimonial.

16 Ibid.

17 Omaha World-Herald, August 17, 1938.

18 According to Frank Graham, The New York Giants: An Informal History of a Great Baseball Club (New York: Putnam, 1952), 107-108.

19 The writer was unable to find a definitive purchase price in contemporary news accounts of the Giants sale, with most guesstimates offering the $1 million figure. See, e.g., the Chicago Tribune and New York Times, January 15, 1919. But a recent Giants history put a $1.3 million price tag on the sale of the club. See Tom Schott and Nick Peters, The Giants Encyclopedia (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, Inc., 1999), 90.

20 McQuade assumed the treasurer post formerly filled by Ashley Lloyd, while John B. Foster held over as club secretary until McGraw, who disliked Foster, arranged his removal.

21 As specified in the decision of the New York Court of Appeals in McQuade v. Stoneham, 263 N.Y. 323, 189 N.E. 234 (1934).

22 The Inferior Courts Act, NY Laws of 1910, ch. 659.

23 Charles Stoneham did not court press or public attention but seemed incapable of eluding it. Long before he entered the baseball world, cutthroat business practices and a scandalous personal life had made Stoneham a familiar figure to readers of the financial and gossip pages of New York dailies.

24 The Hempstead overture was first reported in the New York Sun, October 14, 1922, and thereafter in the New York Times, October 26, 1922, and The Sporting News, November 2, 1922.

25 See The Sporting News, November 23, 1922.

26 After Hempstead, those reportedly approaching Stoneham about selling his Giants stock included former Yankees co-owner Til Huston, boxing promoter Tex Rickard, circus impresario John Ringling, New York construction magnate William F. Kenny, the Madison Square Garden corporation, and bricklayers boss J. Henry McNally.

27 See Graham, 174-178.

28 As per the New York Times, May 3, 1928, which pointedly observed that this was the first known instance of a club treasurer being severed in midseason in the interest of “harmony,” and that heretofore, a treasurer had never “been deemed either an asset or a liability in regard to the play of a team upon the field.”

29 Ibid.

30 As belatedly reported in the New York Times and by Associated Press wire, December 28, 1928.

31 As reported in various AP outlets. See, e.g., the Macon (Georgia) Telegraph and New Orleans Times-Picayune, November 14, 1929.

32 As per the Chicago Tribune, New York Times, and various AP outlets, December 25, 1929.

33 As summarized in the Omaha World-Herald and Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, December 27, 1929, and specifically detailed in the New York Times, January 7, 1930.

34 The minority shareholders suit instituted by William F. Kenny appears to have gone dormant after Kenny lost interest in the Giants and sold his club stock in August 1930. In any event, its disposition was undiscovered by the writer, who presumes that the suit was eventually dismissed for lack of prosecution. The same outcome is likely regarding the Stoneham lawsuit against McQuade, its allegations having been subsumed into the defense of the suit subsequently instituted by McQuade against Stoneham and McGraw.

35 As reported in the New York Times and various AP outlets, July 2, 1930.

36 As per the New York Times, December 10, 1930.

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid.

39 Despite the appellation, the New York State Supreme Court is a trial-level tribunal. The state’s court of final resort is the New York Court of Appeals.

40 Space limitations preclude an accounting of the personal and business iniquities of Charles Stoneham. Still, it would have been interesting if counsel had inquired into the two separate wives (Johanna Stoneham in Jersey City and Margaret Stoneham in Westchester County) who, unbeknownst to each other, each identified Stoneham as her husband to 1930 US Census takers.

41 As reported in the New York Times, December 18, 19, and 22, 1931. See also, the Chicago Tribune and San Diego Evening Tribune, December 22, 1931.

42 As reported in the New York Times and AP outlets nationwide, December 23, 1931.

43 As reported in the New York Times, Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star, and elsewhere, January 13, 1932.

44 See the New York Times, March 18, 1933.

45 McQuade’s lengthy service as a city magistrate qualified him for a pension, but the law required McQuade to be in city employ on the date that he put his retirement papers in.

46 See the New York Times, December 15, 1933.

47 As reported the Aberdeen (South Dakota) News, Biloxi (Mississippi) Herald, Trenton Evening Times, and newspapers across the country, February 21, 1934.

48 As noted in the New York Times, March 1, 1934.

49 According to McQuade’s obituary in the New York Times, April 7, 1955. Stoneham died of Bright’s disease in January 1936, leaving control of the New York Giants to his son Horace.

50 McQuade v. Stoneham, above.

51 Id., at 263 N.Y. 329.

52 263 N.Y. 331-333.

53 As reported in the New York Times, June 11, 1935.

54 As reported in the New Orleans Times-Picayune, Springfield Republican, and elsewhere, June 27, 1938.

55 New York Times, January 31, 1953. See also Westbrook Pegler, “Dempsey Fight Story Finally Ripened,” Boston American, February 3, 1953.

56 As per the New York Times, May 13, 1955, and Boston American, May 14, 1955.

Full Name

Francis Xavier McQuade

Born

August 11, 1878 at Staten Island, NY (US)

Died

April 6, 1955 at New York, NY (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.