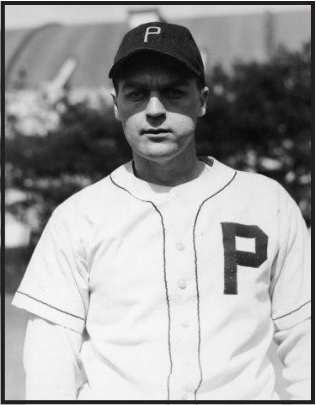

Frank Seward

In two seasons, 1944 and 1945, Frank Martin Seward pitched, mostly in relief, for the New York Giants. His major-league career lasted just six days short of one full year and included only 26 games pitched and eight starts. He enjoyed more success in the minor leagues. His pitching helped the San Francisco Seals win two Governor’s Cup playoffs, in 1945 and 1946, as well as the Pacific Coast League pennant in 1946. After three more seasons in the PCL and the International League, and facing mounting arm injuries, Seward retired from baseball in 1949 at the age of 28.

Seward was born on April 7, 1921, in Pennsauken, New Jersey, a working-class town across the Delaware River from Philadelphia. He was the youngest of four children born to William and Matilda Seward. Frank’s older siblings ranged in age from 4 to 18 when he was born. Another Pennsauken native born a couple of years earlier — Harold Amos, born in 1918 — achieved a different recognition. Educated as a microbiologist, Amos became the first African American department chair (in bacteriology) at Harvard Medical School. In 1933, when Seward was 12, the township hosted, along a seedy section by the Cooper River and neighboring Camden, America’s first drive-in movie.1

A tall (6-feet-3) right-handed pitcher, Seward started in baseball by pitching for the Pennsauken Indians, a semipro team, against traveling teams like the House of David and the Cuban All-Stars.2 When he was a junior in high school, a local petroleum company hosted a tryout near Pennsauken. Pitching against batters wanting to make an impression, Seward struck out eight of the nine he faced. One of the coordinators of the tryout was Jack Coombs, the former Philadelphia Athletics pitcher and a legendary coach at Duke University. Impressed by Seward’s pitching, Coombs announced to everyone “This young man is attending Duke University next year.”3 Only a high-school junior, Seward was dumbfounded. Already considering a scholarship to Western Maryland, Seward weighed his options during his senior year. He chose Duke after the Blue Devils football team lost a close Rose Bowl game on New Year’s Day 1939. While he attended Duke for two years he played only during his sophomore year. During his first semester he broke his right forearm sprinting back to his room during a thunderstorm. In his sophomore year (1941), Seward won three games to help Coombs and the Blue Devils, whose roster included future major leaguers Bill McCahan and Eddie Shokes, earn a winning record. After a bout of appendicitis, Seward left Duke that fall to pursue a professional baseball career.4

Seward then spent the next two seasons in the minors. When he tried to make the Baltimore Orioles of the Double-A International League, he was instead given a letter recommending him to Athletics owner/manager Connie Mack. Having grown up in Pennsauken, this suited Seward just fine. After two weeks watching Seward pitch batting practice for $50 a week, Mack and the A’s decided he didn’t have major-league talent. Meeting with Mack in his office atop Shibe Park, Seward pleaded for just a chance. Mack relented and sent Seward to the Newport News Builders of the Class C Virginia League. Back home in Pennsauken before the train arrived, Seward and his father steamed open Mack’s sealed letter. The contract directed the Newport manager to pay Seward $100 per month. Upon arrival, the Newport manager offered Seward the terms, and the rookie promptly bargained up to $125 a month. Seward appeared in 36 games with a 10-13 record. His 3.45 ERA ranked him third among the team’s pitchers. Seward himself said, “We were in last place; we didn’t have that great a ballclub.”5 Actually the Builders did not fare that poorly; in 1942 they went 62-67, good enough for fourth place. They lost to the Lynchburg Senators in the first round of the league playoffs.6 By this time, of course, the United States had entered WorldWar II. Seward was not drafted because of a perforated eardrum, the same malady that spared the Axis powers from facing Brooklyn Dodgers manager Leo Durocher. Furthermore, Frank’s older brothers, George and Worton, ages 39 and 27, had already been drafted. As the family’s youngest, Frank went undrafted.7

Free to continue in baseball, Seward spent the 1943 season with the Springfield (Massachusetts) Rifles of the Eastern League, a New York Giants affiliate. The Virginia League had folded, so he returned to the Philadelphia area before the season. Seward tried out with the Phillies but manager Bucky Harris sent him to Springfield where his friend, Spencer Abbott, managed. Again one of his team’s younger players, Seward produced numbers that did not change much despite the move to a faster league. He appeared in 35 games with a 10-19 record and a 3.46 ERA.

For one game that year — September 28, 1943, in the season’s last week — Seward made it to the big leagues. The Giants called up him while the Rifles were playing in Binghamton, New York. A rushed overnight train ride ensued. When Seward arrived at the Polo Grounds, the Giants staff originally did not believe his claim that he was the new pitcher.8 Manager Mel Ott decided to spare the rookie the pressure of starting at home, so Seward pitched in his first game at Wrigley Field in Chicago. Up against Paul Derringer, who was seeking his 200th win, Seward pitched a complete game but lost, 3-2 in ten innings. He scattered 12 hits with two strikeouts. The last-place Giants gave him little run support and in the tenth, after he allowed a single and two walks, a routine fly dropped fair for the winning run. After the game the Giants went to St. Louis for a series against the Cardinals. During batting practice at Sportsman’s Park, Seward pitched without a protective net. A Joe Medwick line drive hit his right forearm, fracturing it and ending Seward’s season.9

Seward’s only full season in the majors came in 1944. He started seven games and pitched in 25 contests for the Giants, earning a 3-2 record with a 5.40 ERA. His first appearance came on April 29, when he pitched the last two innings in a 5-0 loss to the Dodgers. His first start came on May 7 in the second half of a doubleheader against the Boston Braves. Seward took the 2-0 loss, giving up six hits before being replaced in the eighth inning. Five days later, in Cincinnati, his next start went poorly. He gave up three hits in the first inning, and then in the second the first two Reds batters got hits, too, so manager Ott pulled him.

Seward earned his first victory on May 31, pitching a complete game in an 8-5 win over the Cubs at the Polo Grounds. Despite giving up two home runs amid six hits, Seward finally received some offensive support. Three Giants homered; one of them, third baseman Nap Reyes, hit two home runs and drove in six runs. In the seventh Seward helped his own cause with an RBI on a squeeze bunt. His second win came on June 18 in Boston when he relieved starter Rube Fischer in the second inning. Seward pitched the rest of game, giving up only two hits and one earned run. He hit a double — one of his two major-league hits — in the 9-2 victory. In his next start, on July 1, Seward lost, surrendering ten hits and five runs to the Cincinnati Reds in 6⅓ innings. His third and final win of the season came on July 7 — a 6-2 victory over the Cubs at Wrigley Field. The next start, on July 16, did not last long. Spotted a two-run lead against the Philadelphia Phillies at Shibe Park, Seward lost the lead in the first inning. He faced two in the second before Ott replaced him. Seward made his last major-league start on July 23, lasting 2⅓ innings in a no-decision against the Cubs. Ott then optioned Seward to the Giants’ Jersey City farm team. Seward posted a 4-6 record with a 3.17 ERA for the Little Giants. He returned to the big-league Giants for one more game on September 22, pitching three innings of relief in an 8-1 loss to the Cubs at the Polo Grounds.

Seward spent the rest of his baseball career, 1945 through 1949, in the minors. For the 1945 season the Giants exchanged Seward and pitchers Ken Brondell and Ken “Whitey” Miller for pitcher Ray “Cowboy” Harrell.10 The Giants’ pitching staff had been one of the majors’ worst (in 1944 their 4.29 ERA was second only to Brooklyn’s 4.68), so the move made sense.11 The three demoted pitchers had combined for 36 game appearances with a 3-4 record and 102⅔ innings pitched (78⅓ of which Seward supplied).

On the other hand, the move west seemed to revitalize Seward. In 1945 and 1946 he went 33-26 for the San Francisco Seals, the Giants’ affiliate in the Pacific Coast League. He thrived in the cool, damp, foggy weather that dominated Seals Stadium. But not at first; he lost his first five starts in 1945. Seward recovered, eventually finishing 18-13. He won two more games in the Governor’s Cup playoffs for 20 total wins. In the first round Seward went 1-1 against Sacramento, the loss coming at home in the ninth inning after the Seals managed ten hits but no runs. In Seattle, in the second game of the championship finals, he gave up a 2-0 lead but recovered for a 4-2 win. Back home in San Francisco for Game Four, Seward won 6-1 to tie the series. The Seals went on to win the Cup, part of the team’s four-year run between 1943 and 1946.12

The next year, 1946, the Seals fans set a minor-league attendance record (670,568), a mark that stood for nearly 40 years.13 The Seals responded, winning the league pennant and Governor’s Cup that year. First baseman Ferris Fain remembered the team quite fondly, as he recalled a four-game sweep of the Philadelphia Athletics during spring training. Fain specifically mentioned the Seals’ pitching. “We had one hell of a pitching staff. To get those kind of numbers that we had that year you gotta have pitching.”14 Contributing to this success, Seward went 15-13 to finish third in wins on the pitching staff, while team ace and future Giant Larry Jansen went 30-6. Ray Harrell, back from the Giants for the 1946 season, finished behind Seward in wins (13) but with a marginally better ERA (2.91).

In the Governor’s Cup championship series, the Seals trailed the Oakland Oaks two games to one but Seward won the fourth game, 6-3, to tie the series. He pitched a no-hitter through six innings, allowed one hit in the seventh and was relieved with one out in the ninth. He even got a hit and scored a run. It was Seward’s biggest game for the Seals and, arguably, in his entire career. The Seals then won the next two games for what would be the team’s last Governor’s Cup victory.15

Seward split the 1947 season between the Seals and the Hollywood Stars, the Chicago White Sox’ PCL affiliate. The Seals had moved Seward to the bullpen after only two starts and then traded him to Hollywood late in the season. In the Southern California heat, Seward appeared in 28 games but started only two. He managed three wins and three losses with a 5.29 ERA, third worst on the team. Hollywood released him, so in 1948 and 1949 Seward pitched for the Syracuse Chiefs, the Reds’ International League affiliate. He finished 6-2 with a 4.37 ERA in 1948. The Chiefs finished second in the league’s Governor’s Cup playoff, losing to the Montreal Royals. The next year, Seward appeared in only ten games with only one start and an 8.40 ERA. Suffering from bursitis and back problems, and losing pitching speed, he retired. He was only 28.16

Seward’s journeyman career on both coasts gave him a unique perspective on great major leaguers of the time. While Mel Ott famously gave Leo Durocher the fodder for the mythical “nice guys finish last” quote, Seward had a noticeably different experience pitching for Ott in New York. Blessed with exceptional baseball talents, Ott needed little coaching and correspondingly provided little. Seward recalled: “Mel Ott was a great ballplayer, but he thought everybody else should be as talented as he. He didn’t have to think about anything; he would just come up there and hit the ball out of the park.”17 Ott’s laissez-faire approach left the rookie Seward without much instruction or encouragement: “I’d have a rough inning and he’d come out, he’d just grab a ball right out of my hand. ‘You’re through,’ he would say.”18 The lack of instruction wasmatched by player treatment. “In the big leagues, it was cutthroat. Nobody would help you out; I mean, nobody ever told me what to do. They’d just give me the ball and say, ‘Throw it. Get ’em out.’ But we didn’t have any kind of exercise machines, whirlpools, etc.”19

On the other hand, the Seals’ longtime manger, Lefty O’Doul, had the people skills Ott lacked. O’Doul had a sense of humor and, importantly for Seward, knew how to manage both star players and those whose talents were not always so evident. O’Doul would leave the successful players alone while encouraging, but not whiplashing, the stragglers. Since Seward himself had bounced around the leagues in a few short years, O’Doul’s comprehensive, nuanced managerial style clearly resonated. Seward considered playing for the Seals better than playing in the majors.20

After baseball, Seward stayed in upstate New York, where he and his wife, Florence, raised two daughters. Needing a job but lacking any qualifications other than his baseball experience, he started at the bottom of the ladder, taking a job at a local Sun Oil filling station. From there he worked his way up to management, first of the station and then for the area. He managed a home-construction company and helped start the Elmira regional housing council. He retired in 1986. When Brent Kelley interviewed him for a book about the San Francisco Seals, Seward said he’d do it all over again, but would be a smarter player. When Kelley responded, “We learn as time passes,” Seward concluded philosophically: “Learn too late.”21 Seward died on April 12, 2004.

Sources

Beverage, Richard, The Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League: A History, 1903-1957 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2011).

Kelley, Brent P., The San Francisco Seals, 1946-1957 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002).

Taylor, Ted, The Ultimate Philadelphia Athletics Reference Book 1901-1954 (XLibris, 2010), 274.

Wells, Donald, Baseball’s Western Front: The Pacific Coast League During World War II (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2004).

Westcott, Rich, Native Sons: Philadelphia Baseball Players Who Made the Major Leagues (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2003), 146.

Dawson, James, “Giant Hopes to Quit Cellar End As Cubs Win, 3-2 in 10th and 2-1,” New York Times, September 29, 1943, 26.

Dawson, James, “Heusser of Reds Scatters 7 Blows to trip Giants, 5-0,” New York Times, July 2, 1944, 53.

Drebinger, John, “Giants Trip Cubs on Reyes’ Hits, 8-5,” New York Times, June 1, 1944, 14.

Strauss, Robert, “The Drive-In Theater Tries a Comeback,” New York Times, July 23, 2004; nytimes.com/2004/07/23/nyregion/drive-theater-tries-comeback-looking-for-few-hundred-adventurous-moviegoers.html, accessed May 27, 2014.

“Frank Seward,” obituary. Elmira (New York) Star-Gazette, April 14, 2004.

archives.com/1940-census/frank-seward-nj-125737474

baseball-reference.com/minors/player.cgi?id=seward001fra

baseball-reference.com/players/s/sewarfr01.shtml

retrosheet.org/boxesetc/S/Psewaf101.htm

thisdaybaseball.blogspot.com/2006/04/april-12th-2004-frank-seward-dies-i.html (author: Richard Barbieri), accessed May 29, 2014.

baseball-reference.com/minors/affiliate.cgi?id=SFG&year=1945

baseball-reference.com/leagues/NL/1943.shtml

baseball-reference.com/leagues/NL/1944.shtml

fa.hms.harvard.edu/about-our-faculty/memorial-minutes/a/harold-amos/

baseball-reference.com/minors/league.cgi?id=521be011

triple-abaseball.com/PostSeasonPCL.jsp

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Governors’_Cup

Notes

1 Robert Strauss, “The Drive-In Theater Tries a Comeback,” New York Times, July 23, 2004.

2 Brent P. Kelley. The San Francisco Seals, 1946-1957, 29, 30.

3 Kelley, 30.

4 Kelley, 30.

5 Kelley, 31.

6 baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Virginia_League#1939-.2740_D_–_1941-.2742_C; accessed June 10, 2014.

7 Kelley, 37.

8 Kelley, 32.

9 Kelley, 33.

10 Kelley, 163.

11 thisdaybaseball.blogspot.com/2006/04/april-12th-2004-frank-seward-dies-i.html.

12 Donald Wells, Baseball’s Western Front: The Pacific Coast League During World War II, 169-70.

13 Kelley, 11.

14 Quoted in Kelley, 16.

15 Kelley, 14, 28.

16 Kelley, 36.

17 Kelley, 29.

18 Kelley, 29.

19 Kelley, 34.

20 Kelley, 29, 34.

21 Kelley, 37.

Full Name

Frank Martin Seward

Born

April 7, 1921 at Pennsauken, NJ (USA)

Died

April 12, 2004 at Elmira, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.