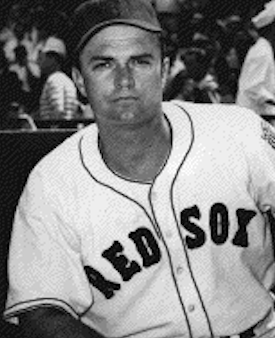

Fred Walters

Catcher Fred Walters worked in 40 games for the Boston Red Sox in 1945. The former Mississippi State football star went on to manage five seasons in the minor leagues and ultimately become a scout for the Red Sox, while officiating both football and basketball for many years.

Catcher Fred Walters worked in 40 games for the Boston Red Sox in 1945. The former Mississippi State football star went on to manage five seasons in the minor leagues and ultimately become a scout for the Red Sox, while officiating both football and basketball for many years.

Fred was his first name, not a nickname; he was born Fred James Walters in Laurel, Mississippi, on September 4, 1912. His father, Artis William Walters, was a farmer and his mother, Pearl (born Candace Pearl Williams), worked as a saleslady in a general store. Fred was their first-born. Two years later Henry joined the family and, seven years after Henry, so did William. It appears that Fred’s father died at some point in the 1920s because Pearl and the three Walters boys are found in the household of Ira Tisdale, in Laurel, at the time of the 1930 census. Pearl had taken Ira’s surname; Ira was a lineman for the electric power company.

Fred Walters attended Mississippi State, from which he graduated in 1937. He earned 12 letters there in college athletics, playing baseball, basketball, and football. The high point of his gridiron career came under football coach Ralph Sasse, on November 2, 1935, at West Point. Playing an undefeated Army team in front of 20,000, halfback Charles “Pee Wee” Armstrong lofted a 30-yard pass to Walters, a substitute end, who caught the pass over his shoulder on Army’s 35-yard line “to dance down the sidelines to a score.”1 It was the final score in the 13-7 game, and the 65-yard touchdown pass made all the difference. He also caught a 40-yard touchdown pass in the 1937 Orange Bowl game in Miami, but Duquesne won, 13-12.

Walters was a forward on the basketball team and a catcher on the baseball team.

Baseball scouts followed his career on the diamond and reports had him “the best prospect developed at Mississippi State since Buddy Myer.”2

On May 15, 1937, the last day of his senior year athletic schedule, he signed with the Boston Red Sox and was farmed out to the Rocky Mount Red Sox, asked to report immediately. Walters provided a little of the background in a handwritten note: “While I was attending college at Mississippi State, I played semipro ball during summer months for teams managed by ‘Happy’ Campbell, baseball coach at the University of Alabama. Through Campbell, who scouts for the Red Sox, I was signed by Billy Evans and was assigned to Rocky Mount in 1937.”3 The Associated Press said, “It was understood that his signature to the contract netted a nice sum.”4

Walters got off to a strong start under manager Nemo Leibold for the Class-B Piedmont League Rocky Mount club, hitting over .300 into late August. We are unable to pin down his final batting average, but an article in the August 20, 1937, Biloxi Herald has him at .309. He is almost certainly the “James Walters” listed with a .294 average for the season in the SABR Minor Leagues Database.

On December 15, Walters married Miss Rose Helen Walker, in Laurel. His younger brother, Harry, was the best man.

Walters trained with the big-league club at Sarasota in the spring of 1938; near the end of March, he was optioned to the Little Rock Travelers in the Class-A1 Southern Association. He played in 102 games for the Travelers, batting .244 with two home runs. One of the homers was a big one, though, a pinch-hit three-run homer that catapulted Little Rock from behind to win the May 28 game in Atlanta.

He caught for the Scranton Miners in 1939, and hit for a solid .299 with six homers.5 He picked up about $400 in bonus money when Scranton won the Eastern League pennant and playoff. In 1940, he caught two games for Louisville at the very beginning of the season, was optioned to San Antonio on May 2 and then, on May 30, optioned to Little Rock, where he played most of the year, this time batting .310 with five home runs.

His 1941 season was spent playing in the International League, for the Montreal Royals. In his first season of Double-A ball, he hit .242 in 80 games. In Double-A ball with Louisville in 1942, he hit a comparable .249.

In 1943, Walters’s career path went in an unexpected direction: he worked as a special agent for the FBI. A note in The Sporting News informed readers that he was due to report for a wartime pre-induction physical on April 10, 1944, adding: “He was out of the game last year and served as a special agent for the F.B.I., a position he was forced to resign because neither his health nor that of his wife could stand a northern climate.”6

He had apparently first joined the FBI in 1941.7

He was not called into military service and did not seem to suffer any health issues playing in Louisville again, appearing in what was a career-high (to date) 129 games and batting for a .278 average. On August 31, his contract was purchased by the Boston Red Sox for delivery in the spring of 1945. Louisville placed third in the American Association standings but prevailed in the playoffs, and faced the Baltimore Orioles (I.L. champions) in the Junior World Series, taken by Baltimore in six games. Walters appeared in five games and was 3-for-17 at the plate with one run batted in.

Given the war, it is remarkable that when the Red Sox mailed out their first contracts for the 1945 season, only one was mailed to a catcher who had any prior major-league experience. Hal Wagner was in military service. Billy Holm and Fred Walters were the only two mailed contracts. They were joined by Bob Garbark in mid-March.

Walters secured a spot on the team during spring training; a 4-for-4 day on April 7 against the New York Yankees didn’t hurt. When the regular season began, it started with Walters catching and batting eighth at Yankee Stadium. He was 0-for-3 with a base on balls (and a caught stealing) in the Opening Day game. He committed one error behind the plate all season, and given that this was his only year in the majors, his fielding percentage for the year – and his career – stands at .993.)

Walters was 6-foot-1 and weighed 210 pounds, apparently looking heavier than he was and earning him the nickname “Whale.”

His first base hit and first run batted in both came in the third game, on April 19, in his ninth plate appearance of the season. He’d entered late in the game, replacing Holm, and doubled in the top of the ninth to tie the game, 3-3, but was thrown out trying to stretch his hit to a triple. The Yankees scored once in the bottom of the ninth and won. He didn’t drive in another run until June 17, the game where he first scored a run. He was batting .200 at the time. It was his 23rd game, but the high point of his season.

Walters’s best day of the year was in a 6-5 loss to Washington at Fenway Park on June 23. He was 2-for-4 with three RBIs. That proved to be 60% of his career RBI total. In the sixth inning, the two runs he drove in put the Red Sox ahead temporarily, but once more misfortune on the base paths did him in. He was picked off second base.8

He only played in seven games in July, and three in August, and thus ended his playing time in the big leagues, on August 9. The Sox bought Red Steiner from the Cleveland Indians off waivers and the very next day and optioned Walters back to Louisville. There he played in 31 games and hit for a .340 batting average. The team got back into the Junior World Series, taking the first three games from Newark (Walters drove in three runs in the third game). Louisville won the series in six games.

His major-league career stats have him with a .172 batting average and the five RBIs.

Walters spent all of 1946 at Louisville again, batting .265 in 132 games. It was his first year managing; he took over as acting manager after Nemo Leibold was suspended for the rest of the season after a June 16 assault on umpire Forrest Peters. The Colonels went 32-14 under Walters and improved from third place at the time of transition to win the pennant yet again, but this time fell to Montreal in the Junior World Series. Leibold had resumed managing in the postseason.9 It was Walters’s own errant throw on a pickoff attempt at second base in the bottom of the ninth inning of Game Four that allowed Jackie Robinson to scamper home from third base with the tying run, sending the game into extra innings. Robinson hit a bases-loaded single in the 10th to win the game. The games at Louisville were marred by vocal hostility toward Robinson on the part of the fans, and Colonels ownership made it difficult for black fans to attend the games at Parkway Field.

On December 3, Walters was named player/manager of the New Orleans Pelicans for 1947. As a player, he couldn’t have done much better. He hit .344 and was named to the Southern Association All-Star team. He led the Pels to a half-game out of first place finish. He placed second in league MVP voting to Mobile’s Cliff Dapper, as it happened another catcher.

In 1948, Walters “asked for and got his release,”10 to manage Birmingham when the Red Sox switched their affiliation from New Orleans to the Barons. The Barons finished in third place but won everything in the playoffs. He himself played in 99 games and batted .272.

In 1949, Walters managed two teams in two different leagues, but not at the same time. He started the season with Louisville, managing the team for which he had played so many years, but after a start of 12-26, the Red Sox named Mike Ryba to take over as manager and announced on May 28 that Walters would work as a Red Sox scout. The scouting job didn’t last even two weeks; he was hired by the Washington Senators-affiliated Chattanooga Lookouts on June 9.

The move back to the Southern Association (and out of the Red Sox system for the first time in his professional career) prompted an outspoken column by the New Orleans Times-Picayune‘s Wm. McG. Keefe. He was himself clearly still angry at the Red Sox for departing New Orleans for Birmingham (“they pulled up stakes here overnight, after having sabotaged the Pelicans through authorized representatives.”).11 Keefe claimed the Red Sox had taken advantage of Walters’s loyalty. Pels owner A.B. Freeman offered Walters the job as GM, as well as manager, but “Walters felt he owed allegiance to the Red Sox.” Then he was shoved aside, in Keefe’s view, at Louisville. He charged the Red Sox with an “obvious effort that was made to ruin his career as a manager.”12 It is not clear if any of this sentiment had ever been expressed by Walters himself.

But it wasn’t just Keefe. F. M. Williams of the Atlanta Constitution wrote, in part, “The Boston Red Sox let the fellow down. Fred left New Orleans to stay in the Red Sox organization and was stepped upstairs to Louisville after guiding Birmingham to the Shaughnessy playoff and Dixie Series titles…It hurt to have them apply the boot, especially the way they did it.”13

The Chattanooga team finished in last place in 1949, inching up only to seventh place in 1950. In October 1950 he was replaced by Jack Onslow, and left the game of baseball.

He worked for 22 years refereeing in the Southeastern Conference, both in basketball and football – continuing the officiating work he had begun back in the offseasons as far back as the 1930s. Walters also owned a part-share in the Holiday Inn at Laurel.

Walters also served as sheriff in his hometown of Laurel, and as sheriff of Jones County, Mississippi. In 1956, he was on the board of the National Sheriffs’ Association.

After a brief illness, he died at Laurel on February 1, 1980, at Laurel General Hospital. Walters was survived by his wife, Helen, and their two daughters, Barbara and Patricia. He is buried in the city.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Walters’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Associated Press, “Southerners Pass Way to 13-7 Win, Marring Cadets’ Perfect Year,” Dallas Morning News, November 3, 1935: Section II, 6.

2 “State’s Catcher,” Daily Herald (Biloxi, Mississippi), April 7, 1937: 7.

3 Handwritten note in Walters’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame. The Alabama coach was D. Tilden Campbell.

4 “Fred Walters Signs To Play with Red Hose,” The Advocate (Baton Rouge), May 16, 1937: 16.

5 At least two different newspapers reported his average as .302. See, for instance, Ben Epstein, “Gazette Sport Gazing,” Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock), May 30, 1940: 12. This column is also the source for the information regarding the bonus money with Scranton in 1939. The .302 average was also reported by the International News Service.

6 Tommy Fitzgerald, “No Kick By Nemo on Numbers; He Counts Up To 40 on Colonels,” The Sporting News, April 13, 1944: 10. Many years later, the Boston Herald also mentioned in passing Walters’s work as an FBI agent. See Larry Claflin, “Casualties Haunt Sox,” Boston Herald, July 7, 1974: 34.

7 “Ex-Pelican Field Boss Walters Dies in Laurel,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, February 2, 1980: 67.

8 Harold Kaese, “Hose Pass Up Many Chances for Victory,” Boston Globe, June 24, 1945: D19.

9 Actually, Leibold managed Game One, but was then suspended 30 minutes prior to Game Two because of how vociferously he objected to Walters’ having been ruled out on an interference play in Game One and then called out on a foul ball catch that had “obviously” (The Sporting News) been caught after hitting the screen. The Louisville players refused to come out of the clubhouse, delaying the game for 25 minutes until Leibold’s suspension was rescinded. Tommy Fitzgerald, “Colonels Stage Sitdown On Leibold’s Suspension,” The Sporting News, October 9, 1946: 27.

10 Associated Press, “Fred Walters Resigns As Manager of Pels,” Atlanta Constitution, October 22, 1947: 10.

11 Wm. McG. Keefe, “Viewing the News,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, June 10, 1949: 30.

12 Ibid.

13 F. M. Williams, “You’ve Got To Admire Mr. Walters’ Courage,” Atlanta Constitution, June 12, 1949: 2D.

Full Name

Fred James Walters

Born

September 4, 1912 at Laurel, MS (USA)

Died

February 1, 1980 at Laurel, MS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.