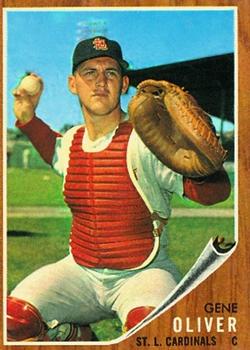

Gene Oliver

Perhaps Gene Oliver was born too soon. With the advent of the designated hitter in 1973, he was already four years removed from his ten-year major-league career. He was a power hitter who drew favorable comparisons to sluggers Frank Howard and Joe Adcock. His glove work was often (and unfairly) derided – making him a prime candidate for the DH slot. Renowned and cherished for his witty humor, he once warded off criticism of his defense by uttering a response worthy of one of the cleverest baseball quotes ever.

Perhaps Gene Oliver was born too soon. With the advent of the designated hitter in 1973, he was already four years removed from his ten-year major-league career. He was a power hitter who drew favorable comparisons to sluggers Frank Howard and Joe Adcock. His glove work was often (and unfairly) derided – making him a prime candidate for the DH slot. Renowned and cherished for his witty humor, he once warded off criticism of his defense by uttering a response worthy of one of the cleverest baseball quotes ever.

Eugene George Oliver was the eldest son and fourth of five children born to European immigrants Marshall and Stella Oliver on March 2, 1935, in Moline, Illinois. Marshall, a farm equipment assembly-line worker, arrived in the United States from Belgium, while Stella, three years his junior, made her way from Poland. It was from her side of the family that Gene later made his contribution to the Cardinals’ “Polish Falcon” brigade that included Stan Musial, Carl Sawatski, Bob Duliba, Bob Sadowski, and Ray Sadecki. A three-sport star athlete at Alleman Catholic High in nearby Rock Island, Oliver accepted a football scholarship to Northwestern University after turning down a $60,000 bonus from Detroit Tigers scout George Moriarty. A shoulder separation on the high-school gridiron ended both his football pursuits and the Tigers’ interest. Though the university changed his scholarship to baseball, the dejected youngster instead returned home, took a job with IBM, and got married. “I was ready to forget about pro baseball, but my wife [Marilyn] insisted I try again because she didn’t want me to go through life wondering whether I might have made it,” Oliver recalled.1.

Oliver rehabilitated his arm under the tutelage of Dave Cox, his former American Legion coach. When the Cardinals’ Midwest scouting chief, Joe Monahan, passed through Moline and inquired about Oliver’s health – he’d not forgotten the 500-foot shot Gene hit over the left-field bleachers in Busch Stadium during an earlier trial – he received glowing reports. On a frigid day in January 1956, Monahan arranged a throwing exhibition inside the local YMCA and, convinced that the shoulder was adequately healed, signed Oliver for a fraction of the amount previously offered by Detroit. Originally assigned to the club’s Class D affiliate in Albany, Georgia (Georgia-Florida League), Oliver was transferred to the Ardmore (Oklahoma) Cardinals, where he terrorized the pitchers in the Class D Sooner State League. A baserunning error on June 20 robbed Oliver of a home run that ultimately prevented him from breaking the league record of 39 in a season. Flirting with the .400 mark through the early season, he finished with a .333 batting average and helped the Cardinals to a first-place finish. This harried pace continued the next year in the Class B Carolina League when Oliver “out-Bilkoed Steve Bilko”2 for the Winston-Salem Red Birds’ home-run record. Oliver’s 30 home runs broke the 1947 mark of 29 set by minor-league slugger Steve Bilko. Cardinals general manager Frank Lane offered that Oliver “could become one of the real long-distance sluggers of baseball.”3 That season at the Cardinals’ direction, Oliver played a number of games as a catcher.

Proving that he could hit a ball out of any park, Oliver continued his torrid pace after reporting to his first major-league spring training camp in 1958. He was described as one of the “most talked-about players”4 with a chance to stick with St. Louis, but was instead assigned to the Rochester (New York) Red Wings of the Triple-A International League. Slowed by an arm injury in May, he finished second on the team with 18 home runs, one behind outfielder Tom Burgess. Oliver’s consistent display of power convinced scribes that the 23-year-old catcher-outfielder-first baseman would replace “The Man” when Stan Musial eventually chose to retire.

“I’ve been [to Rochester]. There’s no point in going back. I think I’ll stay with the Cardinals,” Oliver predicted in March 1959,5 and, based on the team’s lack of power, he seemingly would have been a welcome addition. In the preceding five seasons (1954-1958), St. Louis had one unsuccessful pennant drive and three second-division finishes, due in part to the team’s lack of the long ball (126 homers per year vs. the league average of 149). Yet while this deficit (119 vs. 141) continued over the following three seasons (1959-1961), Oliver’s powerful bat did not find a permanent home in St. Louis until 1962.

Various barriers blocked his advancement. In 1959 an experiment at catcher appeared to be over when Oliver was returned to Rochester to be groomed as a full-time first baseman. After he paced the International League in home runs in the early stages of the season, the parent club beckoned and Oliver made his major-league debut, starting in left field, on June 6. There are certainly better scenarios for one’s debut than facing Philadelphia’s future Hall of Fame right-hander Robin Roberts, but that was the fate that awaited Oliver as he took an 0-for-4 collar with two strikeouts. The tables turned the next day during the first game of a doubleheader when he secured his first hit in typical Gene Oliver fashion – a massive three-run homer into the upper deck in left field in Connie Mack Stadium off righty Ruben Gomez.

Although Oliver broke camp with the Cardinals in 1960, his .182 average in the Grapefruit League (likely because of a hairline fracture discovered in his right hand weeks later) eroded manager Solly Hemus’s confidence in the young slugger. He sat on the bench for 15 days until he was reassigned to the Red Wings. Hemus was even less impressed when Oliver reported to camp in 1961 17 pounds overweight. Used sparingly through the first 24 games, Oliver was returned to the minors on May 16. He proceeded to lead the Pacific Coast League with 36 homers for the Portland Beavers. In Portland the Cardinals moved Oliver back behind the plate and assigned their former catcher, Hal Smith, to work exclusively with him. Pleased with what he saw, Smith stated, [“Gene] did a good job. … [h]is throwing has improved and … he has a good chance to stick in the majors [next] time.”6 Oliver was recalled to St. Louis late in the season and hit .265 with four home runs in 13 starts behind the plate.

In 1962 Oliver was anointed “The Hardest Worker in Camp” for the second consecutive year in an informal poll of sportswriters.7 In a March 30 exhibition he delivered two singles, a triple, and a home run before the watchful eyes of George Sisler, Bill McKechnie, and Branch Rickey (the latter remarking, “I was most impressed with [Gene’s] swing”8). This offensive explosion carried over into the regular season when Oliver sported a .311 average through mid-May while handling most of the catching duties. Surprisingly, the one thing lacking from his arsenal was the homer – only two by the beginning of June. That deficit was cured when Oliver shifted to a lighter bat and produced seven home runs in 24 games over the last month of the season. His season total of 13 home runs as a catcher (he hit another while playing the outfield) tied a team record. But nothing compared to the shot he delivered on the last day of the campaign.

Over the course of 174 home runs struck during his professional baseball career up to September 30, 1962 (not including countless others stroked in the Caribbean leagues), Oliver had developed a reputation for the dramatic. In 1960 with Rochester, he was struck by a pitched ball that resulted in a brief wrestling match between batter and pitcher along the first-base line. In his next at-bat, Oliver belted a 365-foot homer off the same hurler that was the difference in a 5-4 victory. Another such blast from his powerful bat was portrayed by one writer as “belting a home run under conditions which even a Hollywood script writer would hesitate to concoct.”9 Thus it was that Oliver strode to the plate in the eighth inning of a scoreless duel between Dodgers pitcher Johnny Podres and the Cardinals’ Curt Simmons in Los Angeles.

The Cardinals had long since been eliminated from pennant contention, while the Dodgers were desperately seeking a win to avoid a playoff series against the San Francisco Giants. Three days earlier Oliver had helped the Dodgers’ cause with a three-run home run that contributed to a Giants defeat, but a three-game losing streak by the Dodgers resulted in this nail-biting season finale. Having limited the Cardinals to two hits entering the eighth, Podres appeared in complete control. Meanwhile, Oliver had already shown a propensity for success against the Dodgers that continued throughout his ten-year career (a lifetime batting average of .318 with 16 homers against Los Angeles including an eye-popping .392 vs. Sandy Koufax). Oliver drove a sharp line drive over the left-field fence at Dodger Stadium for the only tally of the day and made himself an instant celebrity in San Francisco. When the Giants prevailed in the three-game playoff series, ardent fans made all-expenses-paid arrangements for Gene and Marilyn to attend the first two games of the World Series at Candlestick Park.

When the Cardinals acquired right-handed hurler Ron Taylor from the Cleveland Indians in December 1962, it established the unique scenario wherein the diamond battery of Taylor and Gene Oliver mirrored the Ron Taylor-Gene Oliver quarterback-receiver combo nearby at the University of Missouri. The diamond battery did not last long in St. Louis. Oliver’s slow start in 1963, combined with the club’s desire to find playing time for $80,000 bonus-baby catcher Tim McCarver, cut into Oliver’s time behind the plate. In the final hours of the June 15 trading deadline, Oliver and minor-league pitcher Bob Sadowski were sent to the Milwaukee Braves for pitcher Lew Burdette. With five catchers now on the Braves’ roster, the team optioned Bob Uecker to Denver and announced that Oliver would play first base. Oliver admitted, “I never did like to catch. … Playing [elsewhere] helps my hitting. … Less to worry about and [I] can concentrate on hitting.”10

In his first three games as a Brave, Oliver got six hits in 12 at-bats. For the season, he had 11 home runs in 296 at-bats and tied for fourth on the Braves despite appearing in only 95 games. On July 15 Oliver was one of four catchers used by manager Bobby Bragan in the starting lineup against Cincinnati: Oliver in left field, Joe Torre at first base, Hawk Taylor in center field, and Del Crandall catching.

Even that unusual development did not complete the strangeness of Oliver’s season with the Braves. Facing the Reds on July 28 with one out in the sixth inning of the first game of a doubleheader, Oliver lashed a sure double down County Stadium’s left-field line that third-base umpire Lee Weyer declared foul (even though by some accounts it appeared to have raised a cloud of foul-line lime). Bragan emerged from the dugout to argue the call, insisting that Weyer accompany him to the spot in question, but the umpire refused. “When I told him I was going there anyway,” Bragan reported, “he said ‘You do and you’re out of the game.’ So I went there and I was out of there.” Oliver hit the next pitch over the left-field wall only to find that it didn’t count because time had been called to replace third-base coach Jo-Jo White, who had also been ejected by Weyer. When Oliver was subsequently called out on strikes, he threw his bat and helmet, prompting his own ejection. “I’m the only player in history to get a double, a home run, and a strikeout in the same time at bat,” he said.11 NL President Warren Giles later added to Oliver’s misery by fining him and White $25 for their part in the episode.

Bragan’s continual lineup shuffling made a veritable turnstile out of first base during the 1964 season. In addition to Torre, who manned the post often when newly acquired Ed Bailey served behind the plate, Oliver found himself sharing the position with five other players. The constant platooning (plus time missed to a muscle pull in May) led to only 279 at-bats for Oliver. He muscled 13 home runs, 11 of which won a game, put the Braves ahead, or pulled them into a tie.

Over the offseason the Braves received inquiries about Oliver’s availability from Houston, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles (if only to keep from facing him?), but the team did not budge. The practice of using the 33-year-old veteran Ed Bailey behind the plate lasted only one year when he was traded back to San Francisco. In search of a backup catcher, the Braves turned to the man who’d previously admitted he didn’t like the position. Injuries forced Bragan to rotate Torre and Oliver between the plate and first base. A slow start gave way to Oliver’s blistering second half line of .294-16-39, causing Bragan to remark, “I don’t know where we would have been without him.”12 Still, the last month of the season held even more in store.

Though the large player once described as “roly-poly”13 was never confused for a speedster on the basepaths, he did succeed in hitting an inside-the-park home run against (whom else?) the Dodgers on September 22, 1965. It was the last homer by a Milwaukee Brave in County Stadium. Four days later Oliver stroked his 20th round-tripper against future Hall of Famer Juan Marichal, becoming one of six Braves (affectionately dubbed Milwaukee’s “Murderers’ Row”) who set a then-National League record for the most players with 20 homers in a season.

Oliver saw little playing time when the franchise moved to Atlanta the next year. A healthier Braves squad limited his opportunities, and the team seemed to have cornered the market on first basemen (no fewer than 11 players on the 1966 roster had played the position). In a spring-training collision at home plate, Oliver suffered a torn ligament in his left knee that further limited his time when the season opened, and a .152 average by mid-June indicated that he never got fully untracked. The Houston trade rumor reappeared, and he said, “I called my wife during [one] road trip and she asked me, ‘Should I start packing yet?’”14 Oliver remained a Brave when the trade deadline passed but continued to struggle through the season-long slump, interrupted only when on July 30 he became the eighth Brave – and first Atlanta player – to hit three home runs in one game in a 15-2 romp over the Giants.

Pennant aspirations were high for the Braves in 1967 after they finished 1966 with a 25-10 run. Oliver’s spring began with another injury – this time a broken bone in his throwing hand – but when he recovered he hit .294-3-6 in 34 at-bats. When the team stumbled out of the gate, however, fingers were soon being pointed. One such target became Oliver’s defensive play. In 1966 he and Torre ranked among the league leaders in passed balls, a distinction likely related to the emerging talent of knuckleballer Phil Niekro. A perception arose that a former Braves prospect would be better able to handle the future Hall of Famer, and on June 6, with the team mired in seventh place, Oliver was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies for Bob Uecker. Although Oliver was described as “more feared for his bat than he was respected for his glove,”15 he took great pride in his glove work, and had many defenders. When informed that Braves management had traded him because they wanted Uecker to catch Niekro, Oliver snorted, “There are only three people who can catch knuckleballers – managers, general managers, and sportswriters.”16 It wasn’t long before Gene was able to take his own measure of revenge for the perceived slight.

The Phillies saw the acquisition as an opportunity to improve their offense. Manager Gene Mauch chirped that Oliver’s presence would “give us some punch,”17 a vast understatement considering that at the time of the trade, Uecker and fellow catcher Clay Dalrymple were hitting .171 and .119 respectively. Oliver was inserted behind the plate and proceeded to hit.339 with four homers in his first 59 at-bats. On June 12 during his fourth game with Philadelphia, he found himself opposing his former Atlanta teammates and delivered the game-deciding RBI in a 7-4 victory (a feat he duplicated on September 9). On July 20 against his favorite patsies, the Dodgers, he went 4-for-4 with a two-run homer. Oliver’s home run was the difference-maker in a 1-0 duel with the Pirates on August 26, but he fell into a prolonged slump beginning September 1 that brought his average down to .224. That offseason, Philadelphia columnist Allen Lewis wrote, “[Oliver’s] receiving was better than advertised, but his plate slump left the Phillies with no choice but to go hunting for another catcher.”18 On December 15, Oliver was traded with left-handed pitcher Dick Ellsworth to the Boston Red Sox for 26-year-old catcher Mike Ryan and cash.

Perhaps Oliver’s future in the majors was glimpsed when Boston manager Dick Williams said, “[he] will have every opportunity to make the team. … [h]e can be an excellent pinch-hitter in our ballpark.”19 Was there any question that Oliver would not make the team in 1968? And if he did make it, did Williams perceive him as only a pinch-hitter? The questions became moot when Red Sox catcher Russ Gibson underwent an appendectomy on March 26. But when Gibson returned and Oliver struggled at the plate, the defending American League champions began actively shopping the 33-year-old veteran. After attempts to trade him to Oakland and Cleveland failed, Oliver was sold to the Chicago Cubs on June 27. He was with the Cubs for less than a month when he had to have surgery for torn knee cartilage. He returned to the club in 1969 but was used sparingly and had a brief stint with the Cubs’ Double-A affiliate in San Antonio. On September 2 he was released and named a Cubs coach. He continued as a minor-league instructor in the Cubs and Phillies organizations into the 1980s.

Gene Oliver retired having never accumulated 400 at-bats in a season. More than half of the 580 games he started were played at a position for which he cared little, and he was forced to yield that position to two of the most accomplished catchers of the decade, Tim McCarver and Joe Torre.

His ten-year career – 2,216 at-bats, .246 batting average, 93 home runs, and 320 RBIs– was perhaps best summarized by manager Bobby Bragan in 1965: “[Gene is] one of our unsung heroes. He’s a real spearhead, a go-go guy on the field and off, and a man of great versatility.”20

When his coaching career was over, Oliver went back home to Rock Island, Illinois. He had done sales and public-relations work in clothing stores and car dealerships, and now added the position of part-time bailiff to his résumé. But his true passion centered on his high-school alma mater. He’d taken to broadcasting Alleman High games in 1963 and, with his love of children, continued in one capacity or another with the school until his final days. When the school established an athletic Hall of Fame in 1995, Oliver was among the first inductees. A year later he was inducted into the Quad Cities Sports Hall of Fame. Beginning in 2003 he wrote an occasional newspaper column under the heading “Cub Reporter” in which he offered his musings on the yearly fate of the Chicago Cubs.

Oliver had developed A friendship with Cubs catcher Randy Hundley, when he was Hundley’s backup, and Gene was a regular participant at Hundley’s Cubs Fantasy Camp. The camps were the ideal transition from Oliver’s playing days. In uniform, he had been sought after by sportswriters who wanted a quote on a teammate or opponent, and he readily provided compliments ranging from athletic skills to the attractiveness of teammates’ children. A perpetual student of life, he developed a philosophical approach in his later years by yielding quotes such as “When the student is ready … the lesson appears” or “Every path serves a purpose.”

Gene Oliver’s own path came to an end on March 3, 2007, when he died from complications after lung surgery. He was buried at Calvary Cemetery in Rock Island, and was survived by his wife of 52 years (his high-school sweetheart, Marilyn Daxon); their children, Dana and Daniel; and six grandchildren.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Gene Oliver’s widow, Marilyn, and Alleman High’s Father Daniel Mirabelli for their time and assistance in ensuring the accuracy of this biography. Further thanks are extended to Terry Sloope, Bill Nowlin, Len Levin, and Russ Lake for the editorial and fact-checking contributions.

Sources

The Sporting News

usatoday30.usatoday.com/sports/baseball/2007-03-08-2089856114_x.htm

thedeadballera.com/Obits/Obits_O/Oliver.Gene.Obit.html

brainyquote.com/quotes/authors/g/gene_oliver.html

allemanhighschool.org/athletics/athletics_rahalloffame.cfm

Notes

1 “Cards Counting on Oliver’s Big Bat for Power Pickup,” The Sporting News, November 1, 1961, 21.

2 “Lane Visits Dominican Loop to Check on Three Redbird Garden Candidates,” The Sporting News, October 30, 1957, 9.

3 “’Game Strong Pre-Election Year Tonic in Cuba’ – Lane,” The Sporting News, November 13, 1957, 2.

4 “Hutch, Forced Indoors, Lectures Young Birds on Thinking in Play,” The Sporting News, February 19, 1958, 22.

5 “Gene Oliver’s Long Shots Boost Chance With Cards,” The Sporting News, March 25, 1959, 13.

6 “Sadecki, Keeping Stuff Low, Hitting High Notes for Cards,” The Sporting News, September 13, 1961, 7.

7 “Capsule Comments Pinpoint ’62 Eye-Poppers,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1962, 10.

8 “Alert, Spry Rickey Sounding New Call for Three Majors,” The Sporting News, April 11, 1962, 11.

9 “Oliver Marks Return With Clutch Homer,” The Sporting News, January 14, 1959, 21.

10 “Oliver Whacks Six Hits in Three Tilts for Braves,” The Sporting News, June 29, 1963, 19.

11 “Oliver, White Fined $25 for Weyer Hassle,” The Sporting News, August 10, 1963, 14.

12 “Oliver Rips His Old Benchwarmer Rep With Hot HR Stick,” The Sporting News, October 30, 1965, 12.

13 “Rookie Oliver Packs Wallop – Is He Prize Blaster Cards Need?,” The Sporting News, March 4, 1959, 13.

14 “Braves Cool It as Warm Trade Rumors Swirl,” The Sporting News, June 4, 1966, 17.

15 “Oliver Promoted – Tried Too Hard as ‘Only No. 2,’ ” The Sporting News, August 19, 1967, 16.

16 Ibid.

17 “Phils Leaning On Oliver to Pad 3 Posts,” The Sporting News, June 24, 1967, 10.

18 “Ex-Red Socker Ryan Takes Rosier View as Phil,” The Sporting News, January 6, 1968, 49.

19 “Can Ellsworth Cure Bosox’ Old Malady, Weak Lefty Wings?” The Sporting News, December 30, 1967, 30.

20 “Oliver Catches On as Unsung Hero in Brave Victory Chorus,” The Sporting News, August 21, 1965, 12.

Full Name

Eugene George Oliver

Born

March 22, 1935 at Moline, IL (USA)

Died

March 3, 2007 at Rock Island, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.