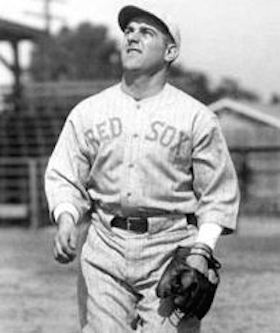

Gene Rye

One of the first things one notices about short-term Boston Red Sox leftfielder/pinch-hitter Gene Rye is that he used another surname while playing professional baseball, apparently Anglicized from Mercantelli. He was also sometimes known by the nickname “Half Pint” – he was 5-feet-6 and weighed 165 pounds. He batted left-handed, but threw right-handed.

One of the first things one notices about short-term Boston Red Sox leftfielder/pinch-hitter Gene Rye is that he used another surname while playing professional baseball, apparently Anglicized from Mercantelli. He was also sometimes known by the nickname “Half Pint” – he was 5-feet-6 and weighed 165 pounds. He batted left-handed, but threw right-handed.

Rye, as we shall call him here, was born to Amadeo Menotti Mercantelli (1866-1950) and Daria “Dora” Frediari Mercantelli (1867-1920), in Chicago on November 15, 1906. By this time, the Mercantellis had been in the United States for a considerable period of time. They had married in Italy in 1888 and arrived in the U.S. later the same year. Their first child, Evelin, had been born just before they left the Old Country. The 1910 census shows Menotti Mercantelli (he seems to have gone by his middle name, not his first) working as a plasterer in the building trade. Evelin was employed as a “typewriter” and had four younger siblings: Florence, 14; Willie, 12; Lucy, 5; and Eugene, 3.

Baseball researcher Ray Nemec reports that Gene’s brother, William Mercantelli, played minor-league ball from 1919 through 1933.1 It was Bill Rye who first began to use the name Rye. The explanation? “It seems he was of dark complexion…and the fellows called him Rye Bread…and when he started playing he called himself William Rye. By the time Gene was ready for baseball, Bill had established himself by the name Rye so Gene just adopted it from his brother.”2

The 1920 census shows Mercantelli working as a plasterer for a lamp manufacturer. Ten years later, he was listed by the first name of John, but both he and Gene (who was listed in the census as “Player, baseball”) kept the last name Mercantelli. Rye may not actually have ever legally changed his name; his 1980 death is noted in the Social Security Death Index as Eugene Mercantelli.

Gene attended the Prescott Elementary School on Wrightwood Avenue in Chicago for eight years, which served as his formal schooling.

Gene Rye began his professional baseball career in 1925 with the Waterloo (Iowa) Hawks of the Class-D Mississippi Valley League. He played 27 games in the outfield, 38 games in all, batting .259 with a pair of home runs. The next year saw him with Rock Island, then Cedar Rapids, two other teams in the same league. He hit .303 with six homers in a combined 85 games. He improved on that dramatically in 1927, batting a reported .385 for the Cedar Rapids Bunnies, but apparently in a relatively small number of games, perhaps only 15 games in the outfield.3 He may have left the Bunnies in midseason to play for the Logan Squares, a noted semipro ballclub in Chicago. The Journal says he played there “the latter part of the 1927 season.”

In 1928 Rye was in the Class C Piedmont League, playing for the Winston-Salem Twins. He made the team early on, going 3-for-4 in each of the first three exhibition games. He was “giving the boys something to talk about,” commented the Greensboro Record, which added that Rye hailed from the “wicked city of Chicago.”4 He was said to be one of the fastest men in camp. He played good defense and in 133 games batted .289 with an even dozen home runs.

Winston-Salem edged out High Point by two percentage points, .617 to .615, in league standings, then edged them four games to three in a best-of-seven playoff.

In 1929 and 1930, Rye played for the Waco Cubs in the Texas League, now graduated to Class-A ball. It was later reported that Winston-Salem didn’t think they could get money from a major–league team for him because he was “too small for an outfielder.”5

He started the 1929 season on the bench, but won a spot in the outfield and hit .284 with considerable power, hitting 19 homers in 129 games. The Dallas Morning News dubbed him a “chubby outfielder” at one point, but before the 1930 season got underway, it acknowledged him as a “fine outfielder, possessor of a powerful arm and a distance clouter.”6 He improved both in batting average and distance clouting in his second year under manager Del Pratt; Rye hit 26 homers and.367. Three of those home runs came in one inning, the 18-run bottom of the eighth inning on August 7 as Waco beat visiting Beaumont, 20-7. It is, understandably, a baseball record that still stands. On opening day and once more during the season, he hit three home runs in a game; both times off three different pitchers.

It’s not surprising that there was a bit of a bidding war for his services at the big-league level. On September 16, the Boston Herald reported that Rye would be joining the Boston Red Sox. The paper said he was “modeled along the lines of Hack Wilson,” in terms of his physical build.

Rye also had an eye for baseball statistics, apparently. When sent his contract for 1931, he wrote back to Red Sox owner Bob Quinn that he’d hit better than Durst, Oliver, Rothrock, Scarritt, Webb, and Winsett – the six outfielders on the 1930 Red Sox – suggesting that perhaps his salary offer should reflect this.7 A bemused Quinn answered him promptly, suggesting that perhaps someone who didn’t understand the difference between major-league pitching and that in the Texas League might do everyone a favor by spending some more time in the minors.8 Not much more than a week later, his signed contract arrived back in Boston, with an apologetic note suggesting that he had perhaps been poorly advised. “Sorry I caused all that trouble,” he wrote, “but I will come down this Spring and show you that I have the goods.”9

He started off well, hitting both a home run and a triple in the first practice game.10 Unfortunately, a couple of days later he broke two bones in his wrist on February 27. He was back in uniform within a couple of weeks, but wasn’t immediately ready to play. The bandage came off on March 30. When the Red Sox went to New York to open the season, he stayed back in Boston to keep working on rehab.

New manager Shano Collins said he didn’t intend the Red Sox to finish last yet again. And they did not. They finished sixth.

Rye pinch-hit once on April 22, but not again until May 2. He got into the game late on May 3 and had another at-bat. He collected his first major-league base hit on May 6 in Philadelphia. Rye appeared in 12 games in May but was batting .167 at the close of the month. He had one good day, 2-for-4 with two bases on balls at Fenway Park on June 2 against the visiting Cleveland Indians. He also drove in his first (and only) big-league run. Four days later, he played in his final game, on June 6.The wrist had not fully repaired itself, and he was batting only .179, with no extra-base hits, three runs scored, and just the one RBI. He’d had 18 chances in the outfield and converted all but one without error. Not only could he not get the bat around as quickly as he had before the wrist injury, but something else may have been taken out of him as well. The Boston Herald reported that he had also become “a bit slow in making a break for a fly ball or a drive to the outfield.”11

On June 9 Rye was probably sent outright to Galveston; contemporary accounts differ. I In effect, he was rejoining his old Waco club, which had moved to Galveston after the 1930 season.12 He is listed as appearing in six games for Galveston in 1931; the wrist injury hampered him badly and on June 17 he asked to be placed on the voluntarily retired list.13 He later played in an exhibition game in October in Rockford, Illinois, billed as a game of major-league all-stars against the Rockford American Legion team. The local team won, 3-1, in part because the only three major leaguers who turned up for the game were Rye, Tony Piet, and Bill Steinecke. The Legion management offered refunds for tickets purchased to any who were disappointed that no other major leaguers had come.14 In December, Rye asked Galveston for his reinstatement.

With his wrist fully functional again, Rye resumed his career in earnest in 1932, appearing in 124 games for Galveston and then Houston. He’d started for Galveston but had been seriously “handicapped by the idea that the Galveston Park is a jinx park for left-handed hitters.”15 The team released him on May 9 and he was signed by the Houston Buffaloes. In a combined 124 games he hit .306 with 10 homers.

In April 1933, the Elmira ballclub of the Class-A New York-Penn League obtained Rye from Houston. At the end of May, he reportedly signed to play with the Logan Squares, the top semipro club in Chicago.16 Perhaps this served as a sort of extended spring training for him, for reasons unclear. A note in late July said that Rye was expected to report to Elmira soon and provide some punch in the outfield.17 He appeared in 60 games for Elmira, batting .315, but was also frequently seen in box scores both in 1933 and 1934 playing center field for the Logan Squares team.

From 1934 through 1936, he played for Davenport in the Western League (also Class A), hitting .315 in 60 games the first year, then .375 but in just 48 games in 1935 (Davenport finished first in the standings that year, but was swept by Sioux City in the first round of the league playoffs), and finally hitting .265 in a fuller 120 games in 1936. His best game came in the 17-5 pasting the Davenport Blue Sox put on the Omaha Robin Hoods on May 21; Rye homered and hit two doubles and drove in six runs.18

Though he was still just 29 years old, he finished his professional baseball career after the 1936 season.

As far as marriages go, Rye (Mercantelli) married a French immigrant with the first name of Marcelle at some point, but the marriage was apparently unsuccessful. She married Valentine A. Baca in 1948 and Gene married Julia Swentko on October 28, 1950.

At the time his brother Bill completed a player questionnaire for the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1959, Gene Mercantelli lived in Niles, Illinois, and worked in the Chicago suburb of Skokie as a screw machine operator for Teletype Corp.

Rye died on January 21, 1980, in Park Ridge, Illinois.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Rye’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Bill Lee’s The Baseball Necrology, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Letter from Ray Nemec to Lee Allen of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, June 17, 1968.

2 Ibid.

3 The Winston-Salem Journal of March 29, 1928 offers the batting average; SABR’s Minor League database (always a work in progress) shows no average but reflects 15 games played in the outfield).

4 Greensboro Record, April 6, 1928.

5 Greensboro Daily News, March 15, 1931.

6 Dallas Morning News, September 15, 1929 and April 5, 1930.

7 Boston Globe, January 13, 1931.

8 Boston Herald, January 23, 1931.

9 Boston Globe, January 23, 1931. “You hit the nail on the head when you said some one told me what to write, and how to get around. I guess I would have been better off if I had listened to myself,” he wrote Quinn.

10 Boston Globe, February 26, 1931.

11 Boston Herald, June 10, 1931.

12 Ibid. The Globe said his release was unconditional, though the Herald wrote that Collins hoped regular work at Galveston would help him.

13 Dallas Morning News, June 18, 1931.

14 Rockford Republic, October 5, 1931. The Republic referred to Steinecke as “Joe Steinecke.”

15 Dallas Morning News, May 11, 1932.

16 Chicago Tribune, May 25, 1933.

17 The Sporting News, July 27, 1933.

18 Omaha World Herald, May 22, 1936.

Full Name

Eugene Rudolph Mercantelli Rye

Born

November 15, 1906 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

January 21, 1980 at Park Ridge, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.