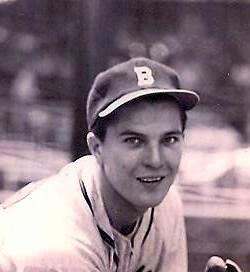

George Estock

George Estock may only be remembered by the most hardcore of baseball aficionados, as he pitched in just 37 games for the Boston Braves in 1951, quietly returning to the minor leagues for another four seasons as part of a 13-year career as a professional baseball player.

George Estock may only be remembered by the most hardcore of baseball aficionados, as he pitched in just 37 games for the Boston Braves in 1951, quietly returning to the minor leagues for another four seasons as part of a 13-year career as a professional baseball player.

Estock was born November 2, 1924, in Stirling, New Jersey, the middle of three children, to Czechoslovakian parents John and Anna Estock. The elder Estock worked as a loom fixer in the silk industry.

Estock was a 1942 graduate of Warren Harding High School in Bridgeport, Connecticut.[1] He was signed to the Scranton Red Sox in 1943 from the semipro leagues in Bridgeport. Estock told the story of how he entered professional baseball. “I was in Scranton in 1943 in spring training. It was a Red Sox farm club. That was the first team I signed with. In Bridgeport, I was playing CYO and semipro on Saturdays and Sundays. A guy named Joe Horesko was working on a defense factory in Bridgeport. He was from a small town Minooka, just outside of Scranton. He came to me one day and asked, ‘Would you be interested in playing pro ball?’ At the time I was living with my father, sister and brother. My mother had died. I was going to school just to get out of school. My father was sort of from the old country. He said, ‘You’re going to go to school and graduate.’ That was his goal. I graduated and signed with the Scranton Red Sox.” [2] His time with Scranton was brief, winning the only game that he pitched before being released. He returned to Bridgeport and continued playing semipro baseball.

While toiling in semipro ball, Estock unexpectedly received a call from Joe Reardon who was the director of minor league operations for the Philadelphia Phillies. “All of a sudden the phone rang and it was Joe Reardon. He was with the Phillies and asked me to try out for their organization, you know, Bob Carpenter and the DuPonts and all of that. I went to spring training with the [Wilmington] Blue Rocks. That was a Philly farm club. To make a long story short, I was there for two years. The second year I won 22 games.” His stellar performance in 1945 with Wilmington earned him a shot at spring training with the Phillies in 1946. “The Phillies brought me up to Spring Training. Herb Pennock was the GM at the time and our manager was Ben Chapman. We trained in Flamingo Park in Miami.” His time with the Phillies was cut short as he was traded before the season started. This trade began a roller-coaster ride of sorts for Estock until he landed in the Braves organization. “That year, I was traded with Tony Lupien to Hollywood in the Coast League. I went to the Coast League and Jimmy Dykes was the manager. Well, he liked the old pros, so they optioned me out to the Eastern League.”

Estock bounced around the next few seasons from Albany to Hollywood to Birmingham before settling in with Austin of the Big State League. “I went to Albany. Rip Collins was the coach there. I had a tough year, not bad and I went back to Hollywood the following year. Again they wanted the older veterans. They sent me to Birmingham. The manager there was Eddie Glenn and the next thing I knew they sold me to a team in Austin. So here I go to Austin in 1947. I played there in 1947-49.” He compiled 48 wins over the three seasons in what would be an eventful stay in Texas. “I got married there. I married a girl from Wilmington, Delaware. We had a son there. Milwaukee was training there in Austin. I was able to pitch in spring training and I pitched a few good games against the White Sox and next thing I knew, they sold me to Milwaukee.”

Nineteen-fifty was a banner year for Estock as he excelled against AAA competition. Milwaukee was in the powerful American Association which had a strong mix of prospects and veterans. He posted a 16-8 record with a respectable 3.35 ERA in 36 games. After his strong performance with Milwaukee, Estock was swept up by the watchful eyes of the Boston brass. “The next thing I knew, the Boston Braves bought me and sent someone else down to the American Association. We trained in Bradenton, Florida. Our manager was Billy Southworth. I went up there and I was 26 years old at the time. It wasn’t easy trying to get to the big leagues when there was eight teams in each league and 100 minor league teams, all trying to get a chance to go to the big leagues.”

He piggybacked his experience negotiating his major-league contract with a story about Hall of Famer Warren Spahn’s attempts to get a raise from general manager John Quinn. “Spahn had won 20 games two or three years in a row. He got a contract for $20,000 from the Braves, from Quinn. He went into the office by himself. You didn’t have lawyers or agents at that time, you went in on your own. He said, ‘Quinny, [you have to have heard Spahn tell it to get the full effect] I want $22,000. I think I deserve a raise, I won 20 games two years in a row, this and that.’ So Quinn looked him in the eye, put his hands on his shoulders, he said, ‘Spahnie, you have a good year this year and we’ll talk about it next year.’ And that was the end of it, what could you do? Here’s $20,000 or you go home. In those days, you were a slave, you belong to them. In other words, if I didn’t sign for $800, I was done. I figured, I got $600 at Milwaukee and I won 16 and you’re sending me a contract for $800, $200 to go to the big leagues? I sent it back and I got it right back. They said, this is the best we can do, we’d like you to sign it, if not we’ll have no further contact. That was the end of it. What could I do? I couldn’t go nowhere else, I belonged to them. My career was over unless I signed with them for $800.”

After signing his contract, Estock stayed with the Braves the entire 1951 season. “My claim was my curve ball and I had a lot of success with it. I was in about 40 games or something like that.” Estock appeared the entire season in relief except for one game. As fate would have it, during his lone start Estock would encounter an opposing pitcher who pitched the game of his career. “I only started one game. To make a long story short, Southworth had a lot of games lined up and he said, ‘George, I’m going to give you a chance, you are going to start against the Pittsburgh Pirates.’ I started against the Pirates and a guy named Cliff Chambers started for Pittsburgh. He pitched a no-hitter and I got beat 3-0. I pitched a good ballgame.”

An unexpected change in leadership cemented Estock’s place in the bullpen. “All of a sudden Southworth got fired and Tommy Holmes became the manager halfway through the season. The Giants and someone else were fighting for the pennant so Holmes didn’t want to take a chance on young pitchers. He had Spahn, Sain, and Bickford and those were his mainstays so I remained in the bullpen.”

Another connection to history that Estock held from his major-league experience was a home run that he surrendered to Willie Mays. “you look in the record books, in 1951, I came in relief in the Polo Grounds. We were tied in the 10th inning. I had two strikes on Mays and Walker Cooper came out and said, ‘George, waste a pitch and come back with that good curve ball. How’s that, ok?’ I said, ‘Sounds great!’ I tried to throw the ball inside and I didn’t get it inside. There was a Chesterfield sign in left field. He hit his 10th home run of his career off of me. He tied the score up in the 10th inning and we got beat in the 11th inning.”

He finished the season with a 0-1 record with three saves and a 4.33 ERA. It was his last foray in the major leagues. “The next thing I knew the following winter, I was sold back to Milwaukee. So in 1952, I played there. Lo and behold the Braves moved to Milwaukee in 1953. When they moved, our franchise moved to Toledo, Ohio. They became the Braves farm club. I played there in 1953 for George Selkirk.”

The 1954 season saw Estock shuttled among the various farm clubs of the Braves system. “I was 29. I started out in 1954 with Toledo. They sent me to Atlanta which was a farm team. Whit Wyatt was our coach – a nice guy, god bless him. I stayed for a month and they called me in. He called me in and said, ‘I want you to go to Jacksonville; you have a lot of knowledge and can help the pitchers and fill in where they need you.’ I went there and became a pitcher for Jacksonville.”

Estock pitched briefly in 1955 for York in the Piedmont League before hanging up his spikes for good. He took work with the DuPont company after leaving baseball in Wilmington. “I met my wife in Wilmington. In the winter as soon as I got done with baseball, I didn’t have any money I had to go right to work. I had an apartment, three children. I went to work with DuPont in the winter. Every winter luckily, I’d get done with baseball in September and have a job. College wasn’t for me, I went to school to get out of school. I stayed in Wilmington and I worked for DuPont. In 1954, they offered me a full time job. I unloaded box cars, I was in the yard gang. I didn’t have any education. I was lucky to get a job. They kept me and I stayed with them for 28 years.” Estock umpired high school and semipro baseball in Delaware for 20 years. He also officiated basketball for 10 years. Estock was inducted into the Delaware Sports Hall of Fame in 1988. [3]

After retiring from DuPont, Estock moved to Sebastian, Florida. “I moved to Florida 25 years ago. The reason I came here because the Dodgers trained in Vero Beach.” Sebastian’s proximity to Vero Beach allowed him to keep in touch with many of his baseball cronies including Tommy Lasorda and Chuck Tanner. “Chuck Tanner was managing the Braves at the time. He was a real good friend of mine. We were roommates. I still have his number and call him. I also keep in touch with Johnny Logan.”

The opening of a new high school in Sebastian allowed Estock to share his passion for baseball with the next generation. “After living here about 10 years they opened a school in this little town of Sebastian just outside of Vero Beach. I went over to the high school and I became the pitching coach for the Sebastian High School. I was a coach until this year [2008]. At first, I said to Buddy Young, the coach, that I would come over for a few days, talk to your pitchers and see if I can help them. I told them little things, keep your eye on the plate, focus on location, make sure you do your running. Things I learned through doing it and other guys telling me it.”

The more he worked with the kids, the better he felt. “It was the best therapy in the world for me, going out there every afternoon. I was able to convey what I had to learn the hard way. If they didn’t believe it, I showed them. I showed them pictures and everything. I had to keep trying to teach them from the shoulders up that it’s not just physical, it’s mental. I still go there every day and I enjoy it. American Legion, same thing. I can’t move like I used to. I have to use a cane to get around. I get out there as much as I can. I talk to the kids and they listen and enjoy it. It’s a nice feeling to know they have respect for you and have them tell you things. I have letters from parents that thanked me. I volunteered there and enjoyed every minute of it.”

Estock was especially proud of one of his pitchers who since the interview made it all the way to the major leagues. “One of my best pupils is Bryan Augenstein. You’ll see him in the Majors. He’s in AAA with Arizona. He’s one of my prized pupils.” Augenstein recently reflected on his coach. “It was very simple with him,” said Augenstein, who was recently claimed off waivers by the St. Louis Cardinals. “He said pitchers should always throw strikes and that’s what I tried to do. He taught us to put in the extra effort to succeed.” [4]

At the time of the interview, Estock was in good spirits even though he had suffered multiple injuries. “I had some disability problems. My hips went, I had my hips replaced four times. I had open heart surgery twice and some other big things. I’m 83, going to be 84 in November [2008].” Looking back at his career, he was appreciative of his time in baseball. “It was an honor, the money was big. The honor of being a player, you felt like you were someone. I enjoy talking baseball. It’s been my whole life.”

George Estock passed away November 7, 2010 at the age of 86 in Sebastian. He was survived by his wife of 62 years, Janet Mae; daughter Lisa Ruzowicz and her husband Tony of Garnet Valley, Pennsylvania; and three sons, George and his wife Bernice of Tampa, Florida, David and his wife Lois of Hockessin, Delaware, and Jeffrey and his wife June of Wilmington, Delaware. [5]

April 4, 2011

[1] George Estock, 1924-2010: Former major leaguer helped teach high school players http://www.tcpalm.com/news/2010/nov/10/former-major-leaguer-helped-teach-high-school/

[2] All quotations from interview conducted with George Estock via phone on August 23, 2008.

[3] Former Blue Rock Estock dies at 86. http://www.delawareonline.com/article/20101112/SPORTS05/11120330/Former-Blue-Rock-George-Estock-dies-at-86

[4] George Estock, 1924-2010, op. cit.

[5] George John Estock Jr. obituary. http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/delawareonline/obituary.aspx?n=george-john-estock&pid=146541189

Full Name

George John Estock

Born

November 2, 1924 at Stirling, NJ (USA)

Died

November 7, 2010 at Sebastian, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.