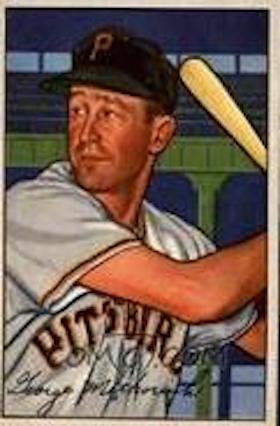

George Metkovich

America as a land of immigrants sometimes produces unexpected surprises. One of them was a Croatian nicknamed Catfish. The outfielder/first baseman George Michael Metkovich played in over 1,000 major-league games from 1943-54, with a career batting average of .261 working for six different big-league teams. He was dubbed “a meteor — never a star.”1

America as a land of immigrants sometimes produces unexpected surprises. One of them was a Croatian nicknamed Catfish. The outfielder/first baseman George Michael Metkovich played in over 1,000 major-league games from 1943-54, with a career batting average of .261 working for six different big-league teams. He was dubbed “a meteor — never a star.”1

Metkovich was born in Angel’s Camp, Calaveras County, California on October 8, 1920. His father John worked as a gold miner, a grinderman in a gold mill. John and his wife Kate (Klaich) were both immigrants from Croatia, John arriving in America in 1901 and Kate in 1907. Both became naturalized U. S. citizens in 1908. They had children — Kris, Helen, Louis, Martin, George, and John.2

John Metkovich died in Fresno in the late 1920s, sometime between 1927 and 1929. At the time of the 1930 census, the family lived in Los Angeles. At least as late as 1943, Kate Klaich still spoke her native Croatian.3 She died in 1984.

George attended Brad Hart (or Bret Harte) School for grades one through nine, and then graduated from Fremont High School in Los Angeles. He’d planned to go on to college and become a physical education coach, but his talents on the ballfield opened up opportunities in baseball. Metkovich also played basketball in high school. He was first-team All-City in 1938-39.4 At Fremont High, he played for Leo Haserot, the same coach who had helped develop Bobby Doerr, Mickey Owen, Steve Mesner, Jerry Priddy, and Hal Spindel.

All the Metkovich boys played baseball in high school. Chris signed professionally and played center field with Macon in 1937.5 He reportedly got as far in professional ball at Houston in the Texas League.6 In early 1947, younger brother John Metkovich signed to play pro ball. In 1952, he was still in pro ranks, playing for Ottawa, and in 1953 for Sacramento.

George played semipro baseball in 1938. He was just 17 when he was spotted and signed by scout Marty Krug of the Detroit Tigers, who signed him to a Beaumont, Texas contract. George graduated during the winter of 1938-39. He went to spring training with Beaumont and was assigned to play for the Fulton (Kentucky) Tigers in the Class-D Kitty (Kentucky-Illinois-Tennessee) League. He put in a full 1939 season for Fulton, playing every one of the team’s 126 games as their first baseman while batting for a .310 average, with 12 homers, 10 triples, and 40 doubles. Fulton finished seventh in the eight-team league. At the end of the season, he got into three games at Class C, with Henderson Oilers of the East Texas League—and went 0-for-6.

Then he was emancipated—set free by the January 14, 1940, “emancipation proclamation” issued by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, which made him a free agent. Metkovich and 92 other players in the Detroit system were all declared free agents at once, a harsh penalty Landis imposed to punish the Tigers after a nine-month investigation that characterized the club as having “mis-handled” the players. Five major leaguers and 88 minor leaguers were all “set free” at once. Reportedly the team acted to “cover up” its players in “wholesale violation” of the rules.7 The commissioner also fined the Cubs and Browns for meddling, i.e., contacting some of the Tigers players before they truly became free agents. He warned other clubs of stronger action if they didn’t handle player transactions more properly in the future. The action hadn’t come out of the blue; two years earlier, he had similarly freed 100 players in the Cardinals system.

George played semipro winter baseball in Los Angeles, and Boston Bees (the Braves were the Bees from 1936 through 1940) manager Casey Stengel signed the new free agent on February 13.8 In making the announcement, Secretary John Quinn said, “Casey saw a lot of him in winter baseball circles out on the coast this season, and it was at the manager’s instigation that we acquired him. Casey is crazy about this lad.”9 There had been some competition for his services, and the team had had to pay him a bonus for signing. He was 6-feet-1 and weighed 165 pounds, batting and throwing left-handed. By 1941, he’d filled out and put on another 20 pounds.

Metkovich picked up his nickname at Bradenton, Florida, during spring training in 1940 with the Bees. “You’ve heard of a lot of injuries to ball players,” Stengel told sportswriter Frederick Lieb, “but you can’t tie this one. I’ve got a young first baseman by the name of Metkovich, who’s in the hospital. Do you know how? He was attacked by a catfish. . . . That catfish almost took his leg off.”10

Metkovich himself told Lieb the story in some detail:

One day after practice, Wilbur McElroy, a young Brave pitcher, and I were fishing off a bridge over the Manatee River. Wilbur pulled up a three-foot catfish, one of the biggest you ever saw, but the ‘cat’ swallowed the hook, and McElroy couldn’t get it out. “Give it a yank, will you?” So I yanked, but nothing happened: I couldn’t get the hook out. So I put the catfish on the bridge, put my foot on its back and tugged. In its dying gasp, that catfish raised a sharp fin out of its back — a sort of extra fin, I guess, and stuck it right through the bottom of my crepe sole shoe! It penetrated the bottom of the foot and almost came out at the instep. McElroy and I worked with it, but we couldn’t get that fin out of my foot. It was a saw-tooth fin, and broke off. They took me to the Bradenton hospital, where they had to give me a local anesthetic. I couldn’t play ball for a week, and for some time afterwards I had to play with a sponge on my foot.”11

Stengel quipped, “It couldn’t have been a catfish. It must have been filet of sole.”12

During his playing career, he was often as not simply called “Cat,” a nickname of a nickname.

Another injury robbed him of much of the 1940 season. Optioned to Boston’s Evansville Bees in the Class-B Three-I League, he tore a ligament in his knee sliding into second base during the June 7 game in Springfield. He was carried off the field and spent a good part of the season unable to play, coming back in time for 50 more games in the final couple of months; he managed only a .227 batting average. The knee still bothered him the following spring, and Boston had so many outfielders that they worked him out at first base. The Evansville Bees, though, used him as an outfielder. He hit .287, with nearly a third of his hits for extra-bases, including 30 doubles. Evansville (with a lot of help from pitcher Warren Spahn) won the 1941 pennant.

In 1941, Metkovich married Peggy Morrison.

Advancing to the Single-A Eastern League with the 1942 Hartford Bees may have been a little too much for the 21-year-old Metkovich. He started the season well, but after the first month he “failed to live up to advance notices” and tailed off sharply.13 He hit .238 in 90 games. On July 31, he was returned to Evansville, played in 35 more games, and hit .308.

With the country at war, Metkovich was classified 1-A and expected to be called to service at any time. He asked the Braves if they would let him play closer to home. The San Francisco Seals offered $500 to buy his contract, which the Braves accepted on March 17, 1943, a conditional deal that allowed them to bring him back any time until June.14 Working under Seals skipper Lefty O’Doul helped him, and he starred for San Francisco, drawing numerous comparisons to Ted Williams—though with a stronger outfield arm.15 The Braves, though, never pulled the trigger to exercise their option and bring him back. Possibly they lost their rights to him, once again thanks to Landis. The Boston Globe reported that the commissioner had “stepped in and declared Metkovich the full property of the Seals.”16

Metkovich fully credited O’Doul, “Until I got to Lefty, nobody had spent any time coaching me at the plate, I’d had to go along, picking up what I could by myself. . . . But O’Doul really went to work on me and he has a swell way of teaching you.”17

After his first 71 Pacific Coast League games, he was hitting .325. And the Boston Red Sox, themselves decimated by players leaving for the service, purchased his contract for a reported $25,000 (and outfielder Dee Miles) on July 6, 1943.18 Despite the Seals second place in the standings, and Metkovich’s being considered “the backbone” of the team, Seals ownerCharley Graham was under heavy financial pressure to pay off a large mortgage by September, or lose his ballclub. Scout Ernie Johnson had recommended Metkovich to the Sox, and Boston manager Joe Cronin had actively pursued the possibility.19

At age 22, Metkovich made his major-league debut for the Boston Red Sox on July 16 in Washington. He was 0-for-4 with two strikeouts. (In an exhibition game against the Washington Senators at Camp Meade on July 14, he had homered and singled.) It wasn’t until his third game that he got his first hit in the big leagues, but in the July 18 doubleheader he was 1-for-4 in the first game and 2-for-5 with a double in the second. His first RBI came in the first game on the 21st at Fenway Park against the White Sox. He drove in the first run of a three-run rally in the bottom of the eighth that propelled the Red Sox from a 2-0 deficit to a 3-2 win. Three days later, facing the St. Louis Browns, he hit his first home run, a three-run shot that was part of a four-RBI, 3-for-5 day, and the winning hit in the 5-3 game.

By season’s end, he had played in every game (78) since he’d joined the team, all but two in either right field or center. He’d batted .246 (.294 OBP), driven in 27 runs, and scored 34. He had five home runs, and recorded a .955 fielding percentage. His career fielding percentage in the majors was .976.

He played some ball in Los Angeles after the season, including a memorable exhibition game against Satchel Paige and the Baltimore Colored Giants. Playing in the Southern California Winter League was brought to a halt when Landis announced he would fine him and 13 other major leaguers for violating the rules against playing postseason exhibition games.20

At some point, Metkovich was reclassified as 4-F, and thus not as likely to be drafted.

In April 1944, the Sox sold Tony Lupien and handed Metkovich the first-base job. He played 50 games there, though in the end, Lou Finney played more games at first with Metkovich in the outfield. He appeared in 134 games, scoring 94 runs (and driving in 59), with a .277 batting average. Probably his most satisfying game came on June 1 in Cleveland where his three-run homer with two outs in the ninth inning boosted Boston to a 7-6 win over the Indians. He ranked the June 14 game higher, when he hit safely twice on the day his son George Jr. was born. The Red Sox put up a good fight for the pennant, in second place much of the year until late August when they finally lost too many key players to the military. As late as September 16, they were only three games out of first, but then tumbled over the final two weeks to finish 12 games behind.

Opening Day 1945 saw Metkovich set a new major-league record for a first baseman, committing three errors in the same inning. He played 97 games at first base in 1945, only committing 12 additional errors all season (for a .985 fielding percentage.) He drove in 62 runs (batting .260). For whatever reason, Metkovich’s batting average in night games, .421, led the league.21 The Red Sox finished seventh.

With the war over, all the Red Sox stars came back in 1946. The team shot off to 21-3 start, and they never looked back, finishing 104-50, and coasting to the pennant with a 12-game pad. Indeed, the lack of competition in the final weeks may have hurt them when it came to the World Series against the Cardinals.

Rudy York had played first base most of the year, Metkovich working exclusively in the outfield, mostly in right. He appeared in 86 games and hit .246 (though his .333 on-base percentage was the best of his career until the 1951 season), driving in 25 runs, and scoring 42. One of the most exciting plays of his year was his steal of home plate, with Ted Williams at bat, on June 23 against the Indians.

In the World Series, Cronin only put him in twice. He pinch hit for Jim Bagby in Game Four and flied out to left field. And in the final Game Seven, in the top of the eighth inning with Boston trailing 3-1, Metkovich pinch hit for Joe Dobson with one on and nobody out. Facing Murry Dickson, he doubled to left field, and all of a sudden the Sox had the two runs they needed on second and third. Harry Brecheen came in and got the next two men out, but then Dom DiMaggio tied the game up with a double. But trying to stretch the double to a triple, he came up lame. Thus he wasn’t in center field when Harry Walker hit the ball there in the bottom of the eighth, and Enos Slaughter scored all the way from first on his famous “Mad Dash.” The Cardinals won the game, and the Series, 4-3.

Playing the Cardinals in 1947 spring training, Metkovich hit a homer to win the game on March 25, but he didn’t make the team. On April 1, 1947, the Cleveland Indians purchased Metkovich’s contract from the Red Sox, though the announcement was held until the following day. George’s younger brother John signed earlier in the year with the Minneapolis Millers.22 Arthur Sampson of the Boston Herald wrote that George had seemed to have everything, but fell into prolonged slumps which were difficult to shake.23 As the “meteor, never a star” comment from Harold Kaese had indicated, he had proved “a beautiful, but unsubstantial dream.”24

Not much was made of his acquisition in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, which characterized Metkovich as “one of Boston’s spare outfielders.”25 He saw a lot of duty, though, almost all in center field. Metkovich appeared in 126 games, hit .254, and drove in 40 runs.

He did a roundtrip during the offseason, traded by Bill Veeck on December 9 to the St. Louis Browns (along with $50,000) for Johnny Berardino. He never played for the Browns, however, other than in spring training. His arm, which had bothered him in the latter part of the 1947 season, had still not come around. And since the trade had been conditioned on his arm improving, the Browns returned him to Cleveland on April 20, 1948, and the Indians paid them $15,000. Three weeks later, on May 5, Metkovich was traded to the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League, along with Les Webber for minor-leaguer Will Hafey.

He had a great year with Oakland (reunited with manager Casey Stengel), batting .336 with 23 home runs, 116 runs scored, and 88 RBIs. He was named to the Northern All-Stars at midseason. The Oaks won the PCL pennant and the playoffs.

And he started 1949 with the Oaks at more or less the same pace, batting .337 with 14 homers through his first 77 games. When Gus Zernial broke his collarbone, the Chicago White Sox made a move, offering cash and a player to be named later (Earl Rapp) to bring in Metrovich as a replacement. Back in the big leagues, Metkovich appeared in 93 games where he hit .237 and drove in 45. The White Sox finished sixth; Oakland might have repeated, had it not lost Metkovich. They finished second, five games behind the Hollywood Stars. And then, with him on the team, they won the pennant again in 1950.

Oakland had reacquired him outright from the White Sox in February that year. Metkovich had fallen out with the Chisox in spring training, charging that GM Frank Lane had told him to swing for the fences, while manager Jack Onslow had told him to just go for base hits. Lane said it was sour grapes, that no one else had been willing to bring him to the majors, and that the only time he’d talked with Metkovich was the time the outfielder had complained to him that Onslow wouldn’t let him play because he was chewing bubble gum. “I suggested that Onslow’s reluctance might have been due to the fact that Metkovich had gone to bat 51 times for one base hit.”26

Playing a much longer season in the PCL, he appeared in 184 games, which helped bump up his numbers. After hitting .315, driving in 141 runs, and, scoring 152 George Metkovich was voted the Pacific Coast League MVP in 1950.

The Pittsburgh Pirates took him in the November 1950 major-league draft. He spent the next 2½ seasons playing for the Pirates. Needless to say, Oakland owner Clarence “Brick” Laws was less than pleased. “That’s out-and-out robbery!” he declared. “I paid $25,000 for Metkovich last winter when no major league club apparently wanted him, at least for that kind of money. So he has a big year . . . and now they’re hot to have him back—for [the prescribed draft price of] $10,000.”27

Pittsburgh finished seventh in 1951 and last in 1952, but Metkovich was reasonably productive for them each year, playing in 120 and 125 games respectively. He hit .293 and .271, driving in 40 runs and then 41.

Metkovich played April and May 1953 for the Pirates, too, but Pirates GM Branch Rickey saw it as a good time to market Ralph Kiner, the NL’s reigning home run champion (for all seven years he’d been in the majors), and finally put together a package attractive enough for the Chicago Cubs to acquire him. On June 4, the Pirates sent Kiner, Metkovich (batting only .146 in 41 ABs), Joe Garagiola, and Howie Pollet to the Cubs, receiving in exchange Bob Addis, Toby Atwell, George Freese, Gene Hermanski, Bob Schultz, Preston Ward, and $150,000 in cash. Metkovich hit .234 in 61 games for the Cubs in the remainder of the 1953 season.

On December 7, the Milwaukee Braves bought Metkovich’s contract from the Cubs in a straight cash transaction, for an amount thought to be around $10,000, purchased for “reserve protection.”28 The Braves thought he might offer “valuable left-handed pinch hitting strength.”29 He gave them the bench protection they likely sought. In 1954, Milwaukee used him in 68 games; he batted .276, with 15 RBIs. They were his last games in the majors. On March 4, 1955, he was released.

He still had two more solid years of playing in him. In 1955, he played for Oakland again and returned to glory, with a league-leading .335 batting average over 151 games, with 17 homers and 79 RBIs. He was one of the three outfielders on the league All-Star team. The Oaks finished in seventh place, though.

In 1956, he played for last-place Vancouver (under manager Lefty O’Doul again), appearing in 132 games and batting .294. It was his last full season of play. His contract was sold to Charleston in February 1957. He indicated he might retire instead. Charleston sold his contract to Louisville, which in turn sold it to the closer-to-home San Diego Padres. He began the season playing first base and appeared in 24 games, batting .267. They were his last games in the field. In mid-May, GM Ralph Kiner (his former roommate with the Pirates) asked him to take over for manager Bob Elliott, and Metkovich managed the San Diego Padres for four seasons.

The 1957 Padres finished fourth, moving up to second-place and just 4½ games behind Phoenix in 1958. He was a bit of a fiery manager: in 1957 alone, “I got kicked out of so many games . . . it costs the club $1,150 in fines.”30 The 1959 Padres finished fourth, though only 6½ games off the pace. He didn’t complete the 1960 season, when the team finished fifth.

In late July 1960, he resigned as manager of the Padres “after being criticized by members of the team.”31 Morale had deteriorated, the same problem that cost Bob Elliott his job back in 1957. Metkovich could have remained but felt the team was going nowhere and neither was he. Plus, he was displeased by the way San Diego fans heaped abuse on his wife during games. San Diego Union sports editor Jack Murphy wrote, “He’s never been able to overcome the resentment of following Bob Elliott, perhaps the most popular figure in the history of San Diego baseball.”32 Jimmy Reese replaced him.

In January 1961, he was hired to scout for the Washington Senators, and did that work from 1961 through 1963. His territory included Southern California, Utah, and Arizona. In his first year, he signed Ron Stilwell out of USC.

Metkovich, described at times during his baseball career as a “fashion plate,” had long been a member of the Screen Actors Guild, since he was a high school student in 1938 when an MGM official had been seeking a basketball player for a movie. “I remember Spencer Tracy was in the movie but can’t recall the name of the picture,” he said.33 He received $350 pay for a few days. “I liked the work and tried to follow it every winter since. I’ve been in 11 movies altogether and worked with some of the most beautiful women in the world.” He went on to name Elizabeth Taylor, Rita Hayworth, Doris Day, Kathryn Grayson, Janet Leigh, Esther Williams, and Zsa Zsa Gabor, and films The Jackie Robinson Story, The Stratton Story, Angels in the Outfield, Gilda, Big Leaguer, and All About Love.

Shortly after becoming president of the United States, Ronald Reagan told an anecdote about working with Metkovich, who had a bit part in the film about Grover Alexander. “Metkovich memorized everybody’s lines. Then on the bus back from location, he’d imitate us and give everybody a hard time. One day, he finally got his speaking line. He was supposed to chew out an umpire. We told Metkovich just to yell anything he usually would at an ump. As the camera started rolling, you could tell something was wrong. His bat was shaking. I throw the pitch, the umpire bellows, ‘Strike one.’ George steps out, goes nose to nose with the ump and in this meek voice says, ‘Gee sir, that was no strike.’” After his audience laughed, Reagan added, “The picture wasn’t a comedy, so we couldn’t leave it in.”34

Though he said he hoped to get into the movie business fulltime after baseball, his regular work in the off-seasons was as an airplane inspector. He also owned a restaurant in the Los Angeles area, Metkovich’s Crown Room, located next to Los Angeles International Airport and run by the three brothers Chris, George, and John Metkovich.

George enjoyed hunting and fishing, presumably now warier about catfish. In 1969, both he and Jerry Priddy were working as “executives for a Los Angeles paper company,” making the news when George’s 55-foot cabin cruiser “ran into rocks in San Diego harbor.”35 No one was injured.

In his latter years, Metkovich suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, and in 1991 a Los Angeles Times story raised the alarm that he had taken a car and driven off from his home, saying, “I have to go home”—even though his wife had assured him they both were at home. The next day’s newspaper reassured readers that he had been found at 4:40 AM —”wandering near an El Segundo park asking for directions to a baseball game.” A police lieutenant explained, “He was coherent and incoherent. He said he had been at a ballgame and then said he was looking for a ballgame to go to.”36

George Metkovich died from complications of Alzheimer’s (acute respiratory arrest) at age 74, on May 17, 1995, at a hospital in Costa Mesa, California. He was survived by his wife Peggy and their sons George and David. He is interred at El Toro Memorial Park in Lake Forest, California.

Nearly 20 years after his passing, in 2013, he was inducted into the Pacific Coast League Hall of Fame.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Metkovich’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee.

Notes

1 Harold Kaese, “Metkovich Either Very Good — or Vice Versa,” Boston Globe, April 3, 1947:12.

2 Information comes from the 1920 and 1930 United States census. There may have been a sixth son as well. Kate’s surname was perhaps originally spelled Klaic. Their first-born Kris seems to have become the more Americanized Chris by 1930. There is a possibility that George was born on October 8, 1921 as self-reported on his Social Security application and by Find-A-Grave.com.

3 Bob Stevens, “Metkovich is Sold! Red Sox Buy Seal Star,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 7, 1943, 13.

4 Carl Blume, “Five Schools Place Men On All-City Quintet,” Los Angeles Times, February 10, 1939, A17.

5 See, for instance Associated Press, “Houston Ships Players to Jacksonville Club,” Dallas Morning News, March 28, 1936, II, 5, and “Sam Butz, “Stock and Bolling Ejected and Peaches Divide Pair with Jacksonville,” Macon Telegraph, May 27, 1937, 8.

6 Frederick G. Lieb, “Catfish ‘Attack’ Delayed Metkovich,” The Sporting News, June 21, 1945, 5.

7 Associated Press, “Landis Wields Big Stick in Declaring 93 Detroit-Owned Players Free Agents,” Hartford Courant, January 15, 1940, 10.

8 Ibid.

9 Burt Whitman, “Baseball Trails,” Boston Herald, February 14, 1940, 26.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 “Young Bee First Sacker is Just A Sucker for Catfish,” Evansville Courier and Press, April 14, 1940, 21.

13 “Bissonette Places Self On Active List, Sends George Metkovich To Evansville.” Hartford Courant, August 1, 1942, 9.

14 INS, “Seals Tentatively Get Fielder From Boston,” Sacramento Bee, March 11, 1943,10.

15 See, for instance, Bob Stevens, “Gorgeous Georges — Seals’ Wonderman of Throw,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 11, 1943, 18. “There have been stronger arms,” O’Doul said, “but I’ve never seen one to equal it for accuracy. Never a foot off his target.”

16 Roger Birtwell, “Red Sox Buy Metkovich from San Francisco Seals,” Boston Globe, July 7, 1943, 19.

17 Ed Rumill, “Lefty O’Doul Aided Rookie Red Sox Star,” Christian Science Monitor, July 26, 1943, 13. Rumill quoted Metkovich at length on the work O’Doul had done with him.

18 United Press, July 6, 1943.

19 Bob Stevens, “Metkovich is Sold! Red Sox Buy Seal Star,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 7, 1943, 13. By September 1, Metkovich could have been snapped up for $7,500 in the major-league draft. Boston owner Tom Yawkey knew Metkovich was 1-A and could be taken into the Army at any time, but he approved the transaction nonetheless.

20 Associated Press, “Landis To Fine Big Leaguers Playing Winter Ball on Coast,” Boston Globe, November 17, 1943, 18.

21 Wilbur Adams, “Between the Sport Lines,” Sacramento Bee, March 23, 1946, 10.

22 Daniel W. Scism, “Sew It Seams,” Evansville Courier and Press, January 21, 1947, 10

23 Arthur Sampson, “Metkovich ‘Natural’ Who Didn’t Develop,” Boston Herald, April 3, 1947, 11.

24 Kaese.

25 Alex Zirin, “Indians Are Picked to Wind Up Fourth,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 13, 1947, 20.

26 Associated Press, “Bubble Gum Caused Metkovich Trouble with Sox, Lane Reports,” Washington Evening Star, March 13, 1940, 15.

27 Al Wolf, “Loss of Metkovich Irks Acorn Owner,” Los Angeles Times, November 17, 1950, C1.

28 United Press, “Braves Obtain Metkovich for ‘Reserve Protection,” Boston Globe, December 8, 1953, 22.

29 Bob Wolf, “Braves Get George Metkovich of Cubs in Straight Cash Deal,” Milwaukee Journal, December 7, 1953. A July 1954 column by Sam Levy offered Metkovich the opportunity to present his thoughts on what it takes to be a good pinch-hitter. “Job of Pinch Hitter No Position for Laggard; Catfish Metkovich of Braves Explains Why,” Milwaukee Journal, July 11, 1954.

30 Phil Collier, “Metkovich Banished, Padres Beat Mobile,” San Diego Union, March 24, 1958, 17.

31 “Metkovich Resigns,” Cincinnati Post and Times, July 25, 1960.

32 Jack Murphy, “Wife, Future in Baseball, Keys to Metkovich Decision,” San Diego Union, July 25, 1960, 24.

33 Les Biederman, “Scoreboard,” Pittsburgh Press, March 14, 1952.

34 Thomas Boswell, “Cooperstown Comes to the White House,” Washington Post, March 28, 1981, A1.

35 “Notes…off the cuff,” Plain Dealer (Cleveland), February 1, 1969, 31.

36 “Ailing Ex-Ballplayer, 70, Found Safe in El Segundo,” Los Angeles Times, July 25, 1991, OCB12. The prior day’s story had been headlined “Man, 70, With Alzheimer’s Is Feared Lost.”

Full Name

George Michael Metkovich

Born

October 8, 1920 at Angel's Camp, CA (USA)

Died

May 17, 1995 at Costa Mesa, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.