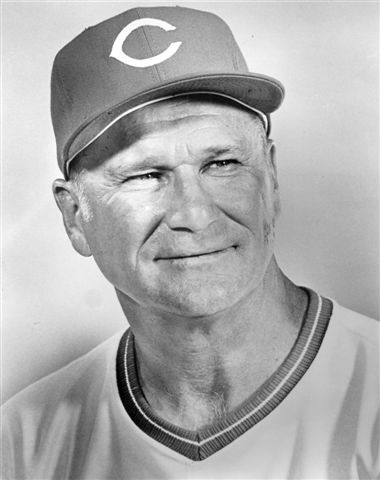

George Scherger

“He knows more about baseball than I’ll ever know,” Hall of Fame manager Sparky Anderson once said of George Scherger.1 Pete Rose, answering skeptics about his own ascension to player-manager in August 1984, told the press not to worry. “I have George Scherger [as bench coach], who just happens to be the smartest baseball man in the world. He’ll keep me from making mistakes, I am sure.”2 Scherger never played or managed in the major leagues, but left his mark over a five-decade career in the game.

“He knows more about baseball than I’ll ever know,” Hall of Fame manager Sparky Anderson once said of George Scherger.1 Pete Rose, answering skeptics about his own ascension to player-manager in August 1984, told the press not to worry. “I have George Scherger [as bench coach], who just happens to be the smartest baseball man in the world. He’ll keep me from making mistakes, I am sure.”2 Scherger never played or managed in the major leagues, but left his mark over a five-decade career in the game.

George Richard Scherger was born on November 10, 1920, in Dickinson, North Dakota, to John and Veronica Scherger. George had three younger brothers, Joseph, Leo, and Donald. The Schergers still lived in Dickinson in 1930, but sometime soon after they moved to Buffalo, New York. George starred in football, basketball, and baseball at St. Joseph Collegiate Institute, an all-boys Catholic high school in Buffalo, graduating in 1940. By high school he had acquired his lifelong nickname of Sugar, though later in life he was often called Sugar Bear.

Scherger signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers out of high school and played 14 years in their farm system. He was a second baseman, about 5-feet-9 and 170 pounds, batting and throwing right-handed. He was a good defensive player who stole a lot of bases for the era but had very little power—just 13 minor-league home runs in 14 seasons. The Dodgers had a very large minor-league system, and Scherger spent most of his time in its lowest levels. He began in Superior, Wisconsin, in the Northern League in 1940, and by the end of the 1942 season had played for four Class D teams.

Scherger then joined the US Army, and eventually the Army Air Corps. He spent most of his three years at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, running the base’s gymnasium. The base library was located above the gym, and he soon began dating the librarian. Mozelle Spainour, a native of Winston-Salem, had degrees from Appalachian State University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.3 The two hit it off. Scherger was discharged as a technical sergeant in early 1946, and on February 23 he and Mozelle were married in Buffalo.

The 25-year-old Scherger reported back to the Dodgers, who sent him to their Danville, Illinois, club in the Three-I League. He hit .243 in his ascension to Class B, and it was becoming clear that he was not going to be a major-league player. The Dodgers saw something else in him, however, and asked him to manage their Kingston, New York, club in the North Atlantic League. He was back at Class D, but on a new career track. “I wasn’t a very good player,” recalled Scherger of his minor-league career. “I was a guy who was enthusiastic and liked to play. They made me a manager at age 26 so you can see how bad I was.”4 He spent ten more years in the Dodgers system as a player-manager.

His first team, in Kingston, won the league pennant, though in midseason Scherger was transferred to another Class D team, in Thomasville, North Carolina. He had his best year as a player with the 1948 Olean, New York, club, hitting .324 in full-time duty. After two years in Trois-Rivieres, Quebec, his 1951 Ponca City, Oklahoma, club ran away with the league pennant. In these years, Scherger occasionally got his name in The Sporting News because of a fracas with an umpire, drawing suspensions at least twice, in 1947 and 1951.5

He spent two seasons in Santa Barbara, California, where in 1953 fate had him cross paths with a young shortstop from nearby Los Angeles named George “Sparky” Anderson. Anderson was 19 and in his first season of professional ball, while his new manager was 32, but the two men both loved the game and were driven to succeed. “Winning was everything to George,” recalled Anderson. “In fact, George believed you should win every night. You know you can’t, but why admit it?”6 Anderson deeply respected his manager, and watched closely. “George could be tough, but he was always fair and considerate,” Anderson remembered. “He knew kids like me could make a lot of errors and he tolerated that, but bonehead plays, mental mistakes, and indifferent attitudes were something else.”7

Years later Anderson and Scherger often reminisced about their days in the minor leagues, and the long bus rides through small towns. “George was one of those guys who believed that once you got on the bus you drove until you got there,” recalled Anderson. “Sometimes it took hours and hours and he wouldn’t allow comfort stops. We’d agitate him and his neck would get redder, but he’d just sit there, staying awake, staring straight ahead.”8

After three more seasons, winning the league playoff in 1954 for Newport News, Virginia, then taking the regular-season pennant the next season for the same club, the 36-year-old Scherger seemingly walked away from baseball after a last place finish with Cedar Rapids, Iowa during the 1956 season. Having seen much of the country in the past ten years, the Schergers had settled in Charlotte, North Carolina. In 1957, Mozelle was hired as the first full-time librarian at Charlotte College, later known as the University of North Carolina-Charlotte. George began working at the local A&P supermarket, helping to raise the couple’s four children—sons George Jr., Joseph, and Daniel, and daughter Teresa.

After four years out of the game, in 1961 Scherger decided to give baseball another go, returning to the Dodgers system to manage. In his first year back, with Panama City, he skippered a 20-year-old second baseman named Bobby Cox. He spent two years in Salisbury, North Carolina, winning the manager-of-the-year award in both seasons, capturing the league title in 1964. After a year with St. Petersburg in 1965, he again left baseball. This time he lasted only a single season away from the game.

Scherger joined the Reds system in 1967, managing Tampa in the Florida State League. Bob Howsam had taken over the Reds and along with farm director Sheldon “Chief” Bender began to remake the organization. In the minors, the Reds wanted their players in great shape and fundamentally sound, and Howsam hired new managers who he believed could provide this kind of discipline: Scherger; Don Zimmer, who began his managerial career in the Reds system in 1967; and Sparky Anderson, whom Howsam hired for the Cardinals in 1965 and then for the Reds in 1968. By 1969 Scherger ran the minor-league spring-training camp, and then took over the Reds’ Gulf Coast League club when the season started in June.

Anderson and Scherger had stayed in touch since their season together in Santa Barbara back in 1953. After one year in the Reds’ system, Anderson was the third base coach for the expansion San Diego Padres in 1969. In October 1969 Howsam shocked everyone by hiring the relatively unknown, 35-year-old Anderson to manage the major-league club. The day he got the job, Anderson called Scherger in Charlotte and asked him to join his coaching staff. After 30 years, Scherger had reached the big leagues.

Scherger initially served as Anderson’s bench coach and also was in charge of coaching defense, both the infielders and the outfielders. When Richie Scheinblum joined the club in 1973, Anderson pointed out Scherger on the field. “Who’s he, the hitting coach?” asked the outfielder. “No, he’s the fielding coach, and a guy I’d like you to know well.”9 In coming years Scherger spent a lot of time working with George Foster and Dan Driessen, two young players who struggled with defense when they started out. “He’s not too old to wield a mean fungo stick,” said Foster. “He can run you all over the outfield until your tongue hangs out.”10 When Pete Rose famously switched to third base in the middle of the 1975 season, it was Scherger who came to the park early every day to hit groundballs to him.

Scherger remained with the Reds for Sparky Anderson’s entire nine-season run with the club, working later at first base and subsequently at third, participating in four World Series and winning two titles. But through all of the success, he continued to work winters at the A&P supermarket back home in Charlotte. “We had four kids to put through college,” he explained. “The kids went to Catholic schools all the way and that cost us too. We’ve been catching up with the World Series money.”11 There were additional perks to the job. After the 1978 season, the Reds team went to Japan to play a series of games. Upon their return, Rose gave each of the team’s coaches a new four-wheel-drive jeep.12

Despite all of the success, soon after their return from Japan, Reds general manager Dick Wagner fired Anderson and his staff. Scherger accepted a job managing their Nashville club, returning to the minor leagues at the age of 58. In midsummer Anderson became the manager of the Detroit Tigers, and there were rumors that Scherger would head to Detroit with him. He decided to finish the season, and soon signed a two-year deal to stay in the Reds organization. He would not be with Nashville, who broke their working agreement with the Reds because they would not allow their affiliates to use a designated hitter, putting their clubs at a decided disadvantage. Despite the handicap, Scherger shepherded the Sounds to the 1979 Southern League championship.

Scherger managed the next three years in Tampa; Waterbury, Connecticut; and Indianapolis. The 1982 Indianapolis Indians were the first Triple-A club he had managed in 23 seasons of minor-league managing. The Indians won their division and then won the American Association playoff as well, earning Scherger the 1982 Sporting News Minor League Manager of the Year award. “I’m tickled pink,” he said. “It’s a real surprise. This has to rate as one of the best things ever to happen to me in baseball.”13 Once again, his success came despite being the only club in the league that did not use the designated hitter. (The team did use one in the pennant race because of a depleted pitching staff.)

At the conclusion of his minor-league season, Scherger joined the Reds’ major-league coaching staff on September 7. The Reds were going through a terrible season, and had replaced manager John McNamara in late July with third base coach Russ Nixon on an interim basis, and there was speculation that Scherger might be in line for the job for 1983. Instead, the Reds rehired Nixon, who kept Scherger as his bench coach. “I would enjoy the opportunity to manage on the major-league level, said the 62-year-old Scherger, “but not at the expense of my good friend Russ Nixon.”14

Scherger remained a Reds coach for four more seasons, working for Nixon and then Vern Rapp. In August 1984 the Reds reacquired Pete Rose from Montreal and made him player-manager. Rose leaned heavily on Scherger. “He’s been a baseball man for 45 years and he has the players’ respect,” said Rose. “The days I’m in the lineup he’ll be running the show.”15 This arrangement lasted through the 1986 season, leading to some debate as to how the team was being managed. Outfielder Gary Redus, who had publicly suggested that Rose was playing himself at the expense of better players (like Redus), also doubted how much managing Rose was doing. “I thought of George Scherger as the manager,” said Redus.16

After the 1986 season Scherger retired from baseball after 47 years (with time off for the Army and two brief retirements). In June 1987 he agreed to return to manage Nashville, but lasted a single game before realizing his mistake. Other than helping Anderson out in spring training a few times, he was retired for good.

He lived out the rest of his days in Charlotte. Mozelle worked as the librarian at UNC-Charlotte for many years before retiring herself in the late 1970s. She died in May 1993, after 47 years of marriage. “She liked helping people and got a great kick out of working with the kids,”’ George said. “And she kept a whole mess of books around.”17

Scherger died on October 13, 2011, at his Charlotte home. He was survived by his three sons, his daughter, two brothers, ten grandchildren, and eight great-grandchildren. He did not make it to the major leagues as a player, but he played a large role on the careers of many who did, and on one of history’s greatest teams.

This biography is included in the book “The Great Eight: The 1975 Cincinnati Reds” (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Mark Armour. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Notes

1# Robesonian [Lumberton, North Carolina], August 19, 1979, 12.

2# Tom Loomis, “Rose at Center Stage With Candor, Charm,” Toledo Blade, 19.

3# “Former College Librarian Mozelle Scherger Dies,” Charlotte Observer, May 30, 1993, 4B.

4# Kim Rogers, “Veteran Scherger Top Pilot,” The Sporting News, December 12, 1982, 48.

5# The Sporting News, July 16, 1947; The Sporting News, July 4, 1951.

6# The Sporting News, October 20, 1973.

7# Ritter Collett, The Men of the Machine (Dayton, Ohio: Landfall Press, 1977), 96.

8# Bluefield (West Virginia) Daily Telegraph, June 2, 1976, 6.

9# The Sporting News, March 24, 1973.

10# Collett, The Men of the Machine, 97.

11# Collett, The Men of the Machine, 96.

12# The Sporting News, December 9, 1978.

13# Rogers, “Veteran Scherger Top Pilot,” 48.

14# Rogers, “Veteran Scherger Top Pilot,” 48.

15# Earl Lawson, “Rose Returns to Run Show,” The Sporting News, August 27, 1984, 37.

16# Paul Attner, “Pete Rose, Manager,” The Sporting News, May 18, 1987, 10-11.

17# “Former College Librarian Mozelle Scherger Dies,” 4B.

Full Name

George Richard Scherger

Born

November 10, 1920 at Dickinson, ND (US)

Died

October 13, 2011 at Charlotte, NC (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.