George Smith

On April 4, 1919, Boston’s Babe Ruth stepped to the plate to lead off the second inning of an exhibition game against the New York Giants at Plant Field in Tampa, Florida. Journeyman right-hander George Smith was on the mound for the Giants, hoping to stick for his third stint with the club after finishing the previous season an eight-game winner – two each for Cincinnati and the Giants and four as a Brooklyn Robin. With the count three balls and a strike, Smith unleashed a fastball to the Red Sox slugger, who responded with a mighty swing. Few if any of the reported 4,200 onlookers in attendance would soon forget what transpired, as the ball left Ruth’s bat on a line to right-center field. Fleet-footed Giants right fielder Ross Youngs was forced to abandon his chase as the ball sailed well beyond the field’s outer marker, finally kicking up some dust when it landed on the far side of a race track beyond the field.

On April 4, 1919, Boston’s Babe Ruth stepped to the plate to lead off the second inning of an exhibition game against the New York Giants at Plant Field in Tampa, Florida. Journeyman right-hander George Smith was on the mound for the Giants, hoping to stick for his third stint with the club after finishing the previous season an eight-game winner – two each for Cincinnati and the Giants and four as a Brooklyn Robin. With the count three balls and a strike, Smith unleashed a fastball to the Red Sox slugger, who responded with a mighty swing. Few if any of the reported 4,200 onlookers in attendance would soon forget what transpired, as the ball left Ruth’s bat on a line to right-center field. Fleet-footed Giants right fielder Ross Youngs was forced to abandon his chase as the ball sailed well beyond the field’s outer marker, finally kicking up some dust when it landed on the far side of a race track beyond the field.

Those who witnessed it called it the longest ball they ever saw struck, and today a historical marker claiming “Babe’s Longest Homer” places the distance of the blast at 587 feet. While both the distance and the claim itself remain subjects of debate, the blast might best be viewed as a preseason indicator that Ruth was about to transform the game with a record-setting 29 home runs during the season. But absent from the marker is any reference to the man who made Ruth’s feat possible, the tall, lanky Smith who was, as it turned out, not long for the Giants roster. He went on to make just three regular-season appearances before a trade in May sent him to Philadelphia.

George Allen Smith signed with John McGraw’s New York Giants on June 27, and made his major-league debut as a Giant against the St. Louis Cardinals on August 9, 1916, fresh off the campus of Columbia University, where he had earned the moniker Columbia George. He’d been seen as a potential “star” by the New York Times as early as his junior year. Noting an April 1915 game in which he struck out 17 Wesleyan batters, the newspaper reported, “It is not Smith’s intention to go into professional baseball.”1

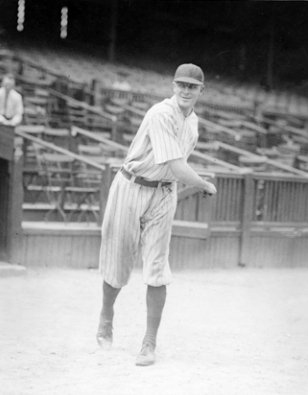

When he ultimately did sign a pro contract, Columbia coach Andy Coakley predicted that Smith would have “a successful career as a big leaguer.”2 The 6-foot-2 Smith, listed at 163 pounds, had a reputation as quiet and bookish off the field, but on the field, “he was an implacable enemy of anybody who wore the uniform of the opposing ball club.3

In the first game of the signing day’s doubleheader, Smith pitched a scoreless inning while striking out two, and after two more brief appearances in relief, won his first career start on September 13 against the Cincinnati Reds. It was in the second game of a doubleheader, and Smith worked 5⅓ innings. (He would have to wait two years before earning his second victory.4) The Times noted, “His debut was a howling success. … He had a world of speed and a curve as round as a barrel hoop. Smithie will do.”5

McGraw was greatly impressed by Smith early on, comparing him to the legendary Christy Mathewson. “Smith, to me, is the Matty of this generation.”6 McGraw compared Smith’s poise, aloofness, and delivery to those of Mathewson and added, “Never before have I seen a young pitcher in whom I have as much confidence as I have in Smith.”7

In nine appearances in 1916, Smith worked a total of 20⅔ innings, and was 1-0 with a 2.61 earned-run average.

In 1917, he trained with the Giants in Texas and pitched 36⅓ innings in 14 regular-season games with a record of 0-3 and a 2.84 ERA. On July 10, he was farmed out to Rochester (International League) for a couple of months, returning to pitch in the Giants game on September 20. He had gotten in a lot of work during his weeks with Rochester, and was 8-11 (2.33) in 178 innings.

Smith was born on May 31, 1892, in Byram, a neighborhood in the town of Greenwich, Connecticut, the only child of Max and Sadie Allen Smith, who had been married for two years.8 Max Smith had emigrated from Germany as a child in 1869. Byram was notable as home to Byram Quarry, which supplied stone for the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge and the base of the Statue of Liberty. Max Smith owned a restaurant in Greenwich, so George had the opportunity to excel in the classroom as well as on the field.

Two years removed from the campus at Columbia, Smith began his 1918 season as a 25-year-old member of the Cincinnati Reds pitching staff, having been purchased from New York on May 2. There he worked under manager Christy Mathewson His stay in Cincinnati was brief and his contributions modest, and by the end of June the Giants had reacquired Smith and his 2-3 won-lost record (4.07 ERA). It was a bizarre scenario, as reported by the Cincinnati Post: “The Reds took Smith on a deal that gave New York no strings on him. But, now that New York is shy on pitchers, John McGraw has appealed to Matty to send Smith back, saying he never intended to let him go and that the deal was made without his knowledge. And Matty, according to reports from St. Louis, is going to fall for it and let Smith return to the Giants.”9 On June 27, Smith returned to the Giants.

He earned just two wins in five decisions with the Giants before again finding himself on the move, this time to the Brooklyn Robins, whom Smith rewarded with a loss and then four complete-game victories through September 2.10 The war-shortened regular season ended on Labor Day in 1918. It was the last year in which Smith enjoyed more wins than losses.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle later reported the Cincinnati sojourn as a loan: “McGraw lent Smith to Cincinnati this season. … Afterward New York reclaimed him. Now New York has turned him over to Brooklyn.”11 And on September 4, the paper reported that Smith was back with the Giants for the third time: “Cincinnati turned him back to New York, which then loaned him to Brooklyn for the rest of the campaign. Smith beat the Phillies in Philadelphia on Labor Day in the last game of the season. His return to the Giants is not due to failure with the Superbas. On the contrary, New York demanded that Brooklyn make the transfer because Smith had shown very promising form with Brooklyn.”12

On December 12, it was reported nationally that the Giants had traded Smith and first baseman Walter Holke to Brooklyn for Jake Daubert. The trade was apparently never consummated.

Smith closed out 1918 by marrying Eva Senst of Port Chester, New York. The marriage took place in secret, and the couple did not announce their nuptials until New Year’s Day.13 News accounts of the marriage indicate that Smith was already teaching mathematics in Greenwich during the offseasons.14

Smith dropped two decisions in his three appearances with the Giants to open the 1919 season before the May 18 trade that sent him and infielder Ed Sicking to the Philadelphia Phillies in exchange for pitcher Joe Oeschger.15 He made 19 starts for the Phillies, posting a 5-11 mark and a 3.22 ERA. The Phillies finished last in the standings, 47½ games behind the pennant-winning Reds, with no pitcher winning more than eight games. His 13 combined losses were eighth worst in the league, and the eight home runs he surrendered were the second most allowed among National League pitchers. Despite a subpar performance on the field, George had good reason to celebrate late in the season. On September 2, his wife, Eva, gave birth to their only child, a son they named George A. Smith Jr.

Smith enjoyed his finest season in 1920, winning 13 games for the Phillies and manager Gavvy Cravath. He pitched 11 complete games and yielded a league-high 10 home runs. His 43 appearances placed him sixth in the league. Among his strongest performances were a 13-inning complete-game win against Brooklyn on May 2, and three weeks later, an 11-inning win against the same club. Despite Smith’s contributions, Philadelphia finished last in the league for the second season in a row, 30½ games behind first-place Brooklyn. His own record was 13-18 (3.45).

That 1920 season proved to be the high-water mark of Smith’s career, and he struggled mightily in 1921 to approximate its modest success. With Philadelphia now being managed by Bill Donovan, Smith began the year with eight losses before gaining his first victory in a complete-game win at Cincinnati on June 18. He went on to win just three more games while losing a league-high 20 for a Phillies team that finished in the cellar with a record of 51-103. After 87 games, Donovan had been replaced as manager by Kaiser Wilhelm. The Phillies won 25 games under Donovan and 26 under Wilhelm.

Smith somehow managed a shutout against the Boston Braves for his final win of the season on August 12, despite allowing 12 hits and a walk with just two strikeouts. He yielded 10 or more hits in 13 appearances during the season, including 20 on two occasions. Philadelphia, scoring the fewest runs in the league while posting the highest team ERA, ended the 1921 campaign 43½ games behind the pennant-winning New York Giants. Smith’s ERA was 4.76, to go with his 4-20 record. He’d eaten up some innings (221⅓), but allowed 303 hits and walked 52 batters.

Smith began his 1922 season with a one-sided loss to the Brooklyn Robins, who would eventually account for six of his 14 losses that season. After June 29, he was used mostly in relief, with four scattered starts, The Phillies saw fit to put Smith on the mound on 42 occasions, 10th most among National League pitchers. In return, he gave them five wins and served up a career-worst 16 home runs, third most among his peers. His seven wild pitches placed third in the league, and on at least one occasion contributed to a fist fight with an opposing team.

Smith faced the New York Giants on April 25 and May 7 and hit Giants outfielder Ralph Shinners with a pitch in each contest. Facing the Giants again on June 29, Smith surrendered six earned runs over seven innings before having his day called for him. In his biography of Giants manager John McGraw, author Charles C. Alexander recounts what happened next:

“George Smith, just lifted for a pinch-hitter, walked past on his way to the visitors’ dressing room and met a shower of McGraw’s choicest obscenities. Smith swung at McGraw and missed, whereupon Shinners rushed between them and took a right to the jaw for his troubles. As Smith and Shinners rolled on the ground, McGraw tried to land a blow on the Phillies pitcher, only to miss and cut Shinner’s cheek. By then players from both bullpens had arrived to break it up. Commissioner Landis was present, but from his box behind first, he complained, he hadn’t been able to see much of the fracas.”16 A later newspaper report said, “They carried Shinners to a hospital, and it was several months before he was ready for action again.”17

The following February, Philadelphia traded Smith to the Brooklyn Robins for left-hander Clarence Mitchell. Brooklyn manager Wilbert Robinson had been impressed by Smith early on, and never forgot him. He hoped he could get something more out of Smith than had the demoralized Phillies.18 In 25 appearances for the Robins in 1923, Smith recorded three wins against six losses. All three wins came within an 11-day span in July, including a 10-inning, complete-game effort on the 28th against the Cincinnati Reds in which he allowed just a single run. It was Smith’s final victory in the big leagues. He was released outright to Indianapolis on February 14, 1924.

With his major-league opportunities having dried up by 1924, Smith managed a 3-5 record in 43 games with the Indianapolis Indians of the Double-A American Association, and led the semipro Wilton Farmers to the Norwalk (Connecticut) City Championship.19

When his playing days were over, the bookish “Columbia” George Smith took to teaching mathematics full-time at Greenwich High School, where he had taught in the offseason since 1919. He retired as the department head in 1957.

His athletic exploits not forgotten, in 1961 Smith was a member of the inaugural class of honorees of the Greenwich Old Timers Athletic Association. Joining him were J.B. Conlon, Tony Manero, Jack Dempsey, Gene Tunney, and George M. Weiss. The dinner held in their honor marked the first time Dempsey and Tunney found themselves seated together since their controversial rematch for the heavyweight title, won by Tunney in 1927.

At the dinner, Smith was asked about the fastball he fired to Ruth all those years ago at Plant Field in Tampa. “I can still see Ross Youngs running back and looking up in the air under that one,” he recalled.20

After a long illness, George Smith died in Greenwich at the age of 72 on January 7, 1965. He is buried at Greenwood Union Cemetery in Rye, New York. His final major-league record was 39-81, with a 3.89 ERA. (His obituary in the Washington Post said it had been 4-81.21

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also relied on Ancestry.com, Baseball-Reference.com, and Smith’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 “Many Stars Among College Pitchers,” New York Times, May 9, 1915: S1.

2 “Giants Get Collegians,” Washington Evening Star, June 28, 1916: 18.

3 Frank Graham, “Smith Was a Hard Fighter,” New York Sun, August 14, 1936.

4 He was not the same George Smith, a 3-year old colt, who won the Kentucky Derby at Churchill Downs in May 1916.

5 The Times also explained to local readers, “He is the lad who used to pitch for Nicholas Murray Butler’s uptown school for boys and girls.” See “Giants Give One to Their Guests,” New York Times, August 10, 1916: 6.

6 “McGraw Finds Second Christy Mathewson,” Charlotte Observer, August 24, 1916: 8.

7 Ibid.

8 Byram was apparently once known as East Port Chester. (Port Chester, New York, was a town just over the state line from Connecticut.

9 “What Sort of Deal Is This?” Cincinnati Post, June 22, 1918: 6.

10 It was widely reported in mid-July that Smith had been traded to the Boston Braves for pitcher Bunny Hearn on June 14. In fact, the Smith in question was infielder Jimmy Smith.

11 “George Smith Joins Superbas,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 3, 1918: 4.

12 “Smith Back With Giants,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 4, 1918: 18.

13 Columbia Alumni News, Vol 10, no. 21, March 14, 1919.

14 “Pitcher Smith Was Secretly Married,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Patriot, January 3, 1919: 9.

15 “Joe Oeschger Traded,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 19, 1919: 14.

16 Charles C. Alexander, John McGraw (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988), 240.

17 “Bean-Ball Spoils Career of Much Touted Rookie Star,” New Orleans States, May 1, 1926: 9.

18 Norman E. Brown, “Perseverance Finally May Bring Success to Pitcher George Smith,” Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, March 5, 1923: 6.

19 thehour.com/wilton/article/Wilton-s-baseball-past-put-on-display-11121817.php. Baseball-Reference.com has Smith on the roster of the St. Petersburg Saints of the Class-D Florida State League, but it must have been for a very brief tenure, as no statistical data is provided. The league disbanded on August 8.

20 Graham.

21 “George Smith Dies, Pitched for Phillies,” Washington Post, January 9, 1962: C2.

Full Name

George Allen Smith

Born

May 31, 1892 at East Port Chester, CT (USA)

Died

January 7, 1965 at Greenwich, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.