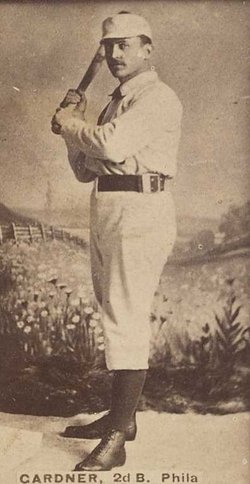

Gid Gardner

As a ballplayer who began his career as a pitcher, converted into an outfielder, and eventually became an infielder, Frank “Gid” Gardner played portions of seven seasons in the major leagues between 1879 and 1888. He compiled a lifetime batting average of .233 in 199 games played, including 15 games as a pitcher, posting a 2-12 career record. While he had talent, his temper and other bad habits prematurely ended his baseball career when he was 30. “Gid Gardner is a good ball player, but he is also a good drinker, and between the two he manages to pull through the season after a fashion,” the National Police Gazette wrote of Gardner in 1888. “Although nearly every club he has played with has had to suspend him for drunkenness, he has always caught on to another job as soon as he is set adrift.”1

As a ballplayer who began his career as a pitcher, converted into an outfielder, and eventually became an infielder, Frank “Gid” Gardner played portions of seven seasons in the major leagues between 1879 and 1888. He compiled a lifetime batting average of .233 in 199 games played, including 15 games as a pitcher, posting a 2-12 career record. While he had talent, his temper and other bad habits prematurely ended his baseball career when he was 30. “Gid Gardner is a good ball player, but he is also a good drinker, and between the two he manages to pull through the season after a fashion,” the National Police Gazette wrote of Gardner in 1888. “Although nearly every club he has played with has had to suspend him for drunkenness, he has always caught on to another job as soon as he is set adrift.”1

Franklin Washington Gardner was born on May 6, 1859, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was the only child of John W. and Sarah (Jewett) Gardner.2 He grew up in East Cambridge, an Irish working-class neighborhood in Cambridge, where his father operated a newsstand and “sold luncheons from a team [of horses] at the Brighton and Watertown cattle markets.”3 Gardner’s nickname, Gid, was an abbreviation of his surname.

Gardner played amateur baseball in Cambridge before joining the semipro Our Boys club in Boston in 1877. He turned professional in 1878 with the Westboro, Massachusetts, club in the New England Association, where he was the primary pitcher. Later that year the Westboro club transferred to the nearby city of Clinton and played as an independent club for the rest of 1878. George Fayerweather, the manager of the Westboro/Clinton club, thought that Gardner would have been a great ballplayer if it weren’t for his temperament. “If Gid hadn’t been so all-fired lazy and stubborn at times, he would have been a star player in the league. He was at times just like a balky horse, and it was necessary to know how to handle him,” Fayerweather said in 1889. “I remember one day we got to the ball field and Gid was missing. I asked Cronin where he was, and he said he had a fit of the sulks and wouldn’t play. I went down to the Clinton House, where we boarded, and found Gid kicking the door jamb, his grip was packed and he was ready to start for Cambridge. I couldn’t get any satisfaction from him, so I went out, borrowed Charley Fields’ team, drove back and ordered him to get in with me. He did so, but sour and ugly as a man could be, but he was over it before we got to the field and he went into the [pitcher’s] box and played one of his great games.”4 That was one of the milder incidents during Gardner’s baseball career.

After the Clinton club disbanded in mid-1879, Gardner played for Worcester of the International Association. He got a tryout in August 1879 with Troy of the National League, pitching two games during the team’s stop in Providence. He lost both games and was released. For the 1880 season the 21-year-old Gardner was the change pitcher for the Cleveland team of the National League, where he periodically spelled Jim McCormick, but pitched primarily in the team’s exhibition games. He pitched well in an exhibition-game victory over Albany on June 15, won his first regular-season game for Cleveland on June 29, and pitched flawlessly in a six-hit shutout against Akron in an exhibition game there on June 30.

However, an incident after the game in Akron derailed Gardner’s baseball career. On the way up the stairs to his hotel room after having a few drinks with his teammates, Gardner made a wrong turn in the dim light, tumbled over a railing, and fell down the atrium through the skylight of the hotel lobby.5 Eerily, it was similar to the fatal accident that had befallen teammate Bill Crook when Gardner played for Clinton in 1878.6 Gardner had cuts, but wasn’t seriously injured, although the fall seemed to impact his pitching arm. He lost every one of his next eight regular-season starts for Cleveland, to post a very poor 1-8 record in the nine regular-season games he pitched.

Starting in 1881, Gardner played more outfield and infield than he pitched. He also never lasted a complete season with any one team, as he became an itinerant ballplayer who journeyed up and down the East Coast to play baseball for whatever club would pay him a few bucks. For the 1881 season, Gardner played for the National ballclub of Washington, D.C., and the Athletic ballclub of Philadelphia, both in the Eastern Championship Association. In 1882 he played for the Philadelphia club in the League Alliance, until he was suspended in August “for indifferent play.”7 He then joined the Merritt club in Camden, New Jersey, in the Interstate Association for the remainder of the 1882 season and the first part of the 1883 season, until the club disbanded in July.

In July 1883 manager Billy Barnie of the Baltimore Orioles of the American Association signed Gardner to play outfield.8 He had his best major-league season in 1883, when he batted .273 in 42 games. He also picked up his second career victory as a pitcher when he relieved the starting pitcher in the fourth inning on August 24 and Baltimore rallied to defeat Louisville.9 However, in a sign of bad things to come, Barnie fined Gardner in September for drunkenness on the team’s trip to New York City.10

Gardner played 41 games, mostly in the outfield, for Baltimore during the first half of the 1884 season before Barnie suspended him in June after he was arrested and put in jail for assaulting a woman.11 Gardner returned to the team after his release on bail, but only a week later was in more trouble. He was arrested and jailed in St. Louis when he and two teammates “found themselves pretty badly loaded [with alcohol] in a disreputable house” and got involved in a melee among the prostitutes and the other johns.12 “Gardner accompanied Madame Abbey to the Four Courts and tried to appease her wrath and smooth the matter over,” the Baltimore Sun reported on the arraignment, “whereupon she struck him a hard blow to the face.”13 Barnie was not as upset as the proprietor of the brothel was, but he wasn’t pleased. “Manager Barnie stated that Gardner has been a disturbing element in his nine,” the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported about the brawl, “and only his fine ball playing has kept him in the ranks.” Now, even his baseball skills could no longer keep him on the team, as Barnie suspended him once again.14 Gardner had no trouble finding new employment, immediately joining the Chicago club in the Union Association, where he played in 38 games, including one game in the pitcher’s box (another loss) on July 17. He returned to Baltimore to play one game at shortstop for the Baltimore club in the Union Association at the end of the 1884 season.

Amazingly, in June 1885 Barnie brought Gardner back to the Baltimore club, this time to play second base. He pitched one last major-league game on July 7, when no other pitchers were available to man the pitcher’s box, and was ineffective as he registered another loss, the 12th of his major-league career.15 While there were no public reports of arrests or other indiscretions during the 1885 season, Gardner had worn out his welcome with both Baltimore and the American Association.

For the 1886 season, Gardner had to go south to secure employment, playing in the Southern League with the club in Charleston, South Carolina. By midsummer he was back in the Northeast, playing with Rochester of the International League. For the 1887 season, he played with the Boston Blues of the New England League until the club disbanded in August. He then caught on with the Indianapolis club of the National League, where he played 18 games during the last month of the season. Although Gardner was back in the major leagues, his tenure in the National League turned out to be brief.

Indianapolis traded Gardner to Washington in exchange for Paul Hines in October 1887. However, Gardner played just one game with Washington in the 1888 season before he was traded again, this time to Philadelphia for Cupid Childs. Gardner played in Philadelphia’s May 5 game against Pittsburgh, which was one of his better games as he went 2-for-3 at bat. However, Pittsburgh protested the game because the trade wasn’t consummated after Childs refused to report to Washington, thus making Gardner an ineligible player for the Phillies.16 When the National League upheld the protest, the May 5 game was dismissed rather than forfeited, and was replayed on July 18.17 Gardner returned to Washington, but couldn’t work out his differences with management. He played his last major-league game on May 29, 1888. When Gardner complained after his release that the Washington ballclub still owed him money, the National League wanted nothing further to do with him.18

Gardner returned to the minor leagues in July 1888 to play for the Easton, Pennsylvania, club in the Central League. However, he was soon suspended from that team for insubordination after he refused to travel with the club to New Jersey “owing to an indictment for an old offense hanging over his head in that state, and he was liable for arrest.”19 In 1889 Gardner played for Evansville, Indiana, in the Central Interstate League, where it didn’t take him long to find trouble. In a game in late June Gardner disagreed with the umpire’s safe call at home plate. “This raised Gardner’s ire, and he came in to dispute the decision,” Sporting Life wrote of the argument. “He was promptly fined $25 for the same, and as that was not enough, he commenced to call [umpire] Hall names, and was ejected from the grounds and placed under arrest.” The Sporting Life correspondent then wrote, “Mr. Gardner should be relegated to the outside ranks and toughs where he properly belongs.”20 In 1890 he played for the semipro ballclub in Norwich, Connecticut. He mysteriously disappeared for a few weeks in the middle of the season, but was cheered by a few hundred fans at the train depot when he returned.21

After his father died in September 1890, Gardner left Organized Baseball to take care of his widowed mother in Cambridge, who lived for another dozen years until her death in 1902.22 He played semipro baseball in 1891 and 1892 with the team sponsored by the Lovell Arms Company, a sporting goods firm in Boston.23 He had no regular occupation after he left baseball. The Cambridge Directory continued to list his occupation as “base-ball player” for several years, but by later in the decade there was no occupation associated with his listing in the directory.24 In the 1900 federal census, Gardner still reported his occupation to be “ballplayer.”25 A 1902 article about him in the Boston Post noted that “Mr. Gardner has retired from active business, being at present unemployed.”26 His obituary in 1914 more bluntly stated, “Since retiring from baseball, he has had no steady employment.”27

After his retirement as a ballplayer, Gardner was a frequent spectator at the games of the Boston Americans in the newly formed American League as well as the games of the older National League team. “I am one of those who believe that the Nationals will hold on,” Gardner said in 1902. “Even if the present owners should sell, there are plenty of good men ready to put their money into baseball. The city can support two teams easily.”28

Gardner died on August 1, 1914, in Cambridge. He is buried at Cambridge Cemetery.

Sources

Egan, James M. Jr., Base Ball on the Western Reserve: The Early Game in Cleveland and Northeast Ohio (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008).

Nemec, David, and Eric Miklich, Forfeits and Successfully Protested Games in Major League Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2014).

“The Clintons of ’78: Manager Fayerweather Gives Reminiscences,” Boston Globe, March 24, 1889.

“Gid Gardner Dead,” Cambridge Chronicle, August 8, 1914.

“What Five Noted Veterans of the Baseball Diamond Are Doing Today,” Boston Post, August 17, 1902.

Baltimore Sun, 1883-1885.

Boston Globe, 1886-1892.

Cambridge Chronicle, 1878-1914.

National Police Gazette, 1888.

New York Clipper, 1877-1890.

Philadelphia Inquirer, 1881-1882, 1888.

Sporting Life, 1885-1890.

BaseballReference.com.

Retrosheet.org.

Cambridge Public Library, Cambridge City Directory from 1883 to 1902.

US Census Bureau, federal census records for decennial years from 1850 to 1910.

Notes

1 National Police Gazette, August 18, 1888.

2 The 1880 federal census, Series T9, Roll 543, Page 117.

3 Obituary of John W. Gardner, Cambridge Chronicle, September 6, 1890.

4 “The Clinton of ’78: Manager Fayerweather Gives Reminiscences,” Boston Globe, March 24, 1889.

5 James M. Egan, Jr., Base Ball on the Western Reserve: The Early Game in Cleveland and Northeast Ohio (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008), 101-102.

6 New York Clipper, July 10, 1880.

7 Philadelphia Inquirer, August 2 and September 6, 1882.

8 Baltimore Sun, July 23, 1883.

9 Baltimore Sun, August 25, 1883.

10 Baltimore Sun, September 6, 1883.

11 Baltimore Sun, June 19-21, 1884.

12 Baltimore Sun, July 3, 1884.

13 Ibid.

14 Baltimore Sun, July 5, 1884.

15 Baltimore Sun, July 8, 1885.

16 Philadelphia Inquirer, May 7, 1888.

17 David Nemec and Eric Miklich, Forfeits and Successfully Protested Games in Major League Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2014), 161.

18 Boston Globe, November 23, 1888.

19 Sporting Life, August 1, 1888.

20 Sporting Life, July 3, 1889.

21 Sporting Life, August 9 and 23, 1890.

22 Obituary of John W. Gardner; obituary of Sarah Gardner, Cambridge Chronicle, September 27, 1902.

23 Boston Globe, June 13, 1891, and July 7, 1892.

24 Cambridge Directory, 1887-1902.

25 The 1900 federal census, Series T623, Roll 656, Page 28.

26 “What Five Noted Veterans of the Baseball Diamond Are Doing Today,” Boston Post, August 17, 1902.

27 “Gid Gardner Dead,” Cambridge Chronicle, August 8, 1914.

28 “What Five Noted Veterans of the Baseball Diamond Are Doing Today.”

Full Name

Franklin Washington Gardner

Born

May 6, 1859 at Boston, MA (USA)

Died

August 1, 1914 at Cambridge, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.