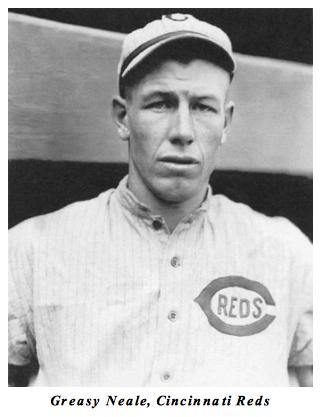

Greasy Neale

Maybe you can visualize the scene from your own living room: “I’ll take ‘Hall of Fame’ for $400, Alex.” Alex says, “I was an outfielder on a World Series winning team, coached in the Rose Bowl, coached back-to-back championship teams in the NFL and was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.” The contestants stare blankly and offer no response. Alex says, “We were looking for Earle ‘Greasy’ Neale. Pick again.”

Maybe you can visualize the scene from your own living room: “I’ll take ‘Hall of Fame’ for $400, Alex.” Alex says, “I was an outfielder on a World Series winning team, coached in the Rose Bowl, coached back-to-back championship teams in the NFL and was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.” The contestants stare blankly and offer no response. Alex says, “We were looking for Earle ‘Greasy’ Neale. Pick again.”

Alfred Earle Neale was born on November 5, 1891 in Parkersburg, West Virginia. He was one of six children born to William and Rena Neale.1 William was employed as a merchant in the wholesale produce industry.

The first question that comes to mind is how on earth William and Rena Neale’s boy received such a nickname. Neale explained, “There was a boy I grew up with in Parkersburg, W. Va., and he was a kind of Huckleberry Finn. His parents didn’t pay him much mind or discipline him in any way. He wasn’t too particular about his appearance, and one day I called him ‘Dirty Face’ or ‘Dirty Neck’ or some such thing, and he got even by calling me ‘Greasy,’ because I had worked for a time as a grease boy in a rolling mill. The other kids picked it up, and it stayed with me for life. Of course, some sportswriters wrote that the nickname referred to my elusiveness as a ball carrier in football and a baserunner in baseball. But it was that boy back home who gave me the name.”2 Later in life, Neale was hired as an assistant football coach at Yale University. The “high-brow set” at the New Haven campus did not approve of his moniker. “No point in changing now just because I’m in the Ivy League,” Neale said.3

Neale left Parkersburg High School after the ninth grade to take a job in the steel mills. However, he returned to school after two years. The school’s football team did not have a coach, and Neale, being the oldest, took the reins of the team. He found that he had an aptitude for coaching and enjoyed mentoring the younger boys on the team.

Greasy Neale enrolled at West Virginia Wesleyan College via a football scholarship in 1912. He was noted for his speedy, slashing running style whether at his familiar end position on the gridiron or stealing bases on the diamond. But he was also a basketball star. He scored 139 field goals one season, in an era when offensive play on the hardwood was slow and methodical.

But his participation in football and basketball was just a means to keep in shape and bide his time until baseball season came around. Baseball was his first and true love, and he never lost sight of his dream of playing professionally.

Neale first signed on with Class C London of the Canadian League in 1912. He knocked around the minor leagues for the next few years, when the trail took him back to his home state of West Virginia and Class B Wheeling in 1915. A friend named Jack Lewis wrote a letter to Cincinnati Reds owner, Garry Herrmann. Lewis recommended that Hermann take a look at Neale. At the time Greasy was tearing up the Central League with his bat, on the way to hitting .351. Hermann dispatched a scout to Wheeling to take a look at Neale. The reports were favorable on the left-handed hitting outfielder, and the Reds signed him.

But Neale had also caught the coaching bug, and while he was about to embark on his major league baseball career, he also started his career coaching football. His first job was in 1915 at Muskingum College, located about 60 miles east of Columbus, Ohio. He joined the Muskies after he wrapped up the baseball season at Wheeling.

Greasy broke into the majors in 1916, becoming the starting left fielder for Cincinnati. Buck Herzog was the Reds skipper and Neale’s favorite manager. “A lot of fellows didn’t like Buck, but I played better ball for him than anyone,” said Neale. “He handled me perfectly. One day, I went to bat four times without even getting a semblance of a hit. I barged into Tommy Griffith’s territory, pulled a fly ball away from him and dropped it. I charged in on a ground ball and it went through me for three bases. I overthrew third base for my third error of the afternoon. I was feeling pretty low about it, but after the game Buck put his arm around my shoulders and told me that my misplays came from trying too hard and not to worry about any of them. Now can you understand why I played my heart out for him?”4

Unfortunately for both Neale and Herzog, Buck was replaced in mid season after posting a 34-49 record. He was sent to the New York Giants on July 20 along with outfielder Red Killefer in exchange for outfielder Edd Roush, pitcher Christy Mathewson and infielder Bill McKechnie. The sun was setting on Mathewson’s brilliant career by then; his acquisition was made to take Herzog’s place in the dugout. Roush, a budding star, was inserted into center field. The move did not sit well with Neale. Although he was just a rookie, he felt that he had earned the right to play center field. Whenever a fly ball went out to left-center, Neale would never call for the ball. But sometimes he would make the play, other times he wouldn’t. Roush had to learn how to watch the ball and Neale at the same time in order to decide to either go after the baseball or cut behind Greasy to let him take it. This went on for about three weeks until Neale decided to stop pouting. “I want to end this Roush,” Neale told him. “I guess you know I’ve been trying to run you down ever since you got here. I wanted that center field job for myself, and I didn’t like it when Matty put you out there. But you can get a ball better than I ever could. I want to shake hands and call it off. From now on, I’ll holler.”5

Neale was being hasty if he thought his new manager was slighting him. Mathewson was well aware of the talents of the young outfielder. “Ambition and headwork,” Mathewson answered when asked about Neale’s best attributes. “This kid’s always on the job, and wants to improve himself and there’s action under his cap. He studies his position and never makes the same mistake twice. Watch his batting next year, for example. He’ll be a greatly improved hitter.”6 Mathewson knew what he was talking about as Neale’s batting average climbed 32 points from .262 his rookie year to .294 his sophomore year.

With Griffith in right, Roush in center, and Neale in left field, the Reds had a formidable outfield. Roush and Neale both had good speed on the base paths, as one or the other led the team in stolen bases from 1917 through 1920.

Neale was the Reds’ starting right-fielder in 1919. His batting average tumbled to .242. Improbably, though, he led the team in hitting in the World Series that year, batting .357 and collecting 10 hits. No other Cincinnati player came even close to him. Perhaps it went largely unnoticed because his hits were of little consequence. Three of his safeties came in the 9-1 shellacking of the White Sox in Game 1. Three more came in a Game 6 loss.

Although the Sox were the favorites to win the series, the Reds were no pushover. Roush led the National League in hitting that year with a .321 average. Jake Daubert, Larry Kopf, and Heinie Groh were more than capable batsmen. The pitching staff was led by Dutch Ruether, Hod Eller, and Slim Sallee. Those three starters won a combined 59 games.

But it was not so much that the Reds won the World Series. As history has revealed, members of the Chicago team conspired to throw the series. The White Sox may as well have put a bow around the World Championship and handed it to the Reds like a Secret Santa.

Regardless of history, Neale was never convinced that the fix was in for more than one game. “I hit .357. Got a triple off little Dick Kerr, the honest pitcher,” Neale told a group one evening at a cocktail party. “Matter of fact, I think they were all honest after that first game. The ones in on the deal didn’t get the payoff they were promised. The rest of the games were straight, I am convinced. Series went eight games, you know.”7

Cincinnati slipped to third place in 1920. Neale had a so-so year, batting only .255 but stealing 29 bases, a career high. He had been shifted to right field, and he led all N.L. right fielders in putouts with 342. Still the Reds packaged Neale and pitcher Jimmy Ring and sent them to the Philadelphia Phillies after the season for pitcher Eppa Rixey.

The next spring, Neale struck a secret deal with the Phillies, by which Neale would be paid $6,000 for the 1921 season. However, after he appeared in only 22 games, the Phillies waived him. Cincinnati claimed him but scoffed at the $6,000 contract. Greasy appealed to Commissioner Landis, who ruled that the Reds were on the hook.

Neale was again on the Reds roster in 1922, but he played sparingly. Then, after a one-year hiatus from baseball to channel his energies toward the gridiron, Neale returned to the Reds in 1924, but appeared in only three games. At 32 years old, his major league career was over. For his career, Neale played in 768 ballgames, batting .259. He totaled 71 doubles, 50 triples, 200 RBI and 139 stolen bases. His career fielding percentage was .972.

But Neale was also keeping busy in the off-season as a collegiate football coach. He returned to his alma mater to coach WVW (1916-1917), Marietta College (1919-1920), Washington & Jefferson (1921-1922), and Virginia (1923-1928). Neale doubled as the baseball coach at both Marietta and Virginia.

Neale had success on the college level. In 1917, his WVW squad was a three-touchdown underdog to intrastate foe West Virginia. But Neale’s boys executed their single wing offense to perfection and blanked the Mountaineers, 20-0. His 1921 team at Washington & Jefferson went undefeated, topping traditional powers Pitt, Syracuse and Detroit. Although there were other teams that went undefeated that year (Cornell, Penn State, and Lafayette, among others), it was a surprise to most when the invitation to the 1922 Rose Bowl was extended to the Washington & Jefferson Presidents. Their opponent would be the California Golden Bears, who were installed as 14-point favorites. Sportswriter Jack James of the San Francisco Examiner remarked “All I know about Washington and Jefferson is that they are both dead.”8

Neale had success on the college level. In 1917, his WVW squad was a three-touchdown underdog to intrastate foe West Virginia. But Neale’s boys executed their single wing offense to perfection and blanked the Mountaineers, 20-0. His 1921 team at Washington & Jefferson went undefeated, topping traditional powers Pitt, Syracuse and Detroit. Although there were other teams that went undefeated that year (Cornell, Penn State, and Lafayette, among others), it was a surprise to most when the invitation to the 1922 Rose Bowl was extended to the Washington & Jefferson Presidents. Their opponent would be the California Golden Bears, who were installed as 14-point favorites. Sportswriter Jack James of the San Francisco Examiner remarked “All I know about Washington and Jefferson is that they are both dead.”8

The Presidents could only afford to send 11 players on the trip west. Although not many gave the Easterners much of an opportunity—outside of W&J that is—Neale was extremely confident. “Nobody gave us a chance,” said Neale. “But I knew what we could do. I told everyone Cal wouldn’t score on us. They just laughed.”9

The game ended in a scoreless tie. A 35-yard touchdown run by the Presidents’ Wayne Brenkert was called back because of an offsides call. The game was notable for other reasons; Washington & Jefferson’s Charles West became first African-American quarterback to play in the Rose Bowl and Herb Kopf (whose brother Larry was a teammate and roommate of Neale’s with the Reds) was the first freshman to appear in the Rose Bowl.10

After his stint at Virginia Neale left college football for a brief hiatus, returning to major league baseball in 1929. “Branch Rickey gave Billy Southworth the managerial post (with the St. Louis Cardinals), and Billy wanted me as his coach. I gave up a good football job to help him, but Southworth was not quite ready for the big time and we only lasted three months. Billy was in a spot in those days because he had to boss a bunch he’d played with—[Frankie] Frisch, [Chick] Hafey, [Jim] Bottomley, Wilson and the rest. Later, when he returned to the Cards, he was set for it.”11

West Virginia University was the next stop for Neale. After three years (1931-1933) in Morgantown, Neale accepted the position of backfield coach for Yale (1934-1940). Neale used the single-wing offense, which emphasized deception (reverses, double-reverses, misdirection plays) and did not rely on a passing game.

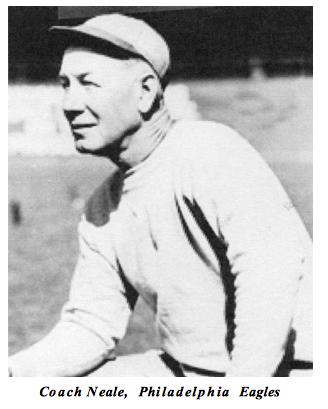

Greasy entered the NFL in 1941, coaching the Philadelphia Eagles for 10 years. Neale was no stranger to professional football. When he was with the Reds in the late 19-teens, he played pro football on Sundays during the off season. Although the Reds had a strict policy forbidding their players participating in other sports, Neale played under the name “Foster” to get around the team rules. Of course, Neale/Foster wasn’t fooling anyone and the Reds just looked the other way. He played/coached for Canton and Ironton. The legendary Jim Thorpe was the coach of the Canton Bulldogs, and occasionally played. In 1917, Thorpe was also a member of the Cincinnati Reds as a spare outfielder.

From 1944 to 1949, the Eagles, who were in the Eastern Division, finished in second place three times and won the division three times. Neale never hid the fact that he would appropriate ideas from other coaches. After Chicago dismantled Washington 73-0 in the NFL Championship game in 1940, Neale bought the game film for $156. He studied George Halas’ T-Formation, and made improvements in it to fit his personnel. He is also credited with using man-to-man defense on pass plays and developing the present-day 4-3 defensive alignment. “I think I was a success as a coach because I wasn’t afraid to borrow something that worked for someone else,” said Neale. “People in the stands never asked you where you got it. They only want to know if you got it.”12

The Eagles lost the 1947 Championship Game to the Chicago Cardinals 28-21. Philadelphia got their revenge the following year, shutting out the Cards 7-0 in 1948. They followed that up with another shutout in the big game, blanking the Los Angeles Rams 14-0 for the 1949 championship. They were the only team to win back-to-back titles by shutting out their opponents.

However a 6-6 record in 1950 led to Neale’s dismissal. “It came as a shock,” said Greasy. “We went 6-6, but we lost five games by a total of 18 points. I guess you have to have a championship team every year to satisfy them.”13

Earle “Greasy” Neale passed away from an undisclosed illness on November 2, 1973, at the Darcy Hall Nursing Home in Lake Worth, Florida. Neale, who had survived two previous wives, had married the former Ola Maurice from Charlotte, North Carolina, on July 26, 1968. He was survived by Ola, a brother, W.H., and a sister, Kathryn.

Greasy Neale was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1967. He was enshrined into the National Football League Hall of Fame in 1969. Alex Wojciechowicz was a member of those championship Eagle teams. Like Neale, he is also a member of both Hall of Fames. “I believe that Greasy Neale, in his time, was the greatest coach in football,” wrote Wojo. “He was the greatest teacher of fair play, a player’s coach. He devoted his life to teaching his men not only spots, but also an understanding and appreciation of life itself. Every player who ever has been coached by him retains an abiding feeling of thankfulness to him.”14

2 Gerald Holland, Sports Illustrated, August 24, 1964.

3 The Sporting News, November 17, 1973, 46.

4 Arthur Daley, New York Times, April 28, 1943.

5 Lawrence R. Ritter, The Glory of Their Times (New York: Macmillan, 1966), 210.

6 Baseball Magazine, February 1917, 572.

7 Gerald Holland, Sports Illustrated, August 24, 1964.

8 http://www.washjeff.edu/rose-bowl-replay

9 Norman L. Macht, Football’s Last Iron Men (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2010), 27.

10 http://www.washjeff.edu/rose-bowl-replay

11 Arthur Daley, New York Times, April 28, 1943.

12 The Sporting News, November 17, 1973, 46.

13 Bill Braucher, Miami Herald, February 7, 1969, 1D.

14 Arthur Daley, New York Times, November 8, 1973.

Full Name

Alfred Earle Neale

Born

November 5, 1891 at Parkersburg, WV (USA)

Died

November 2, 1973 at Lake Worth, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.