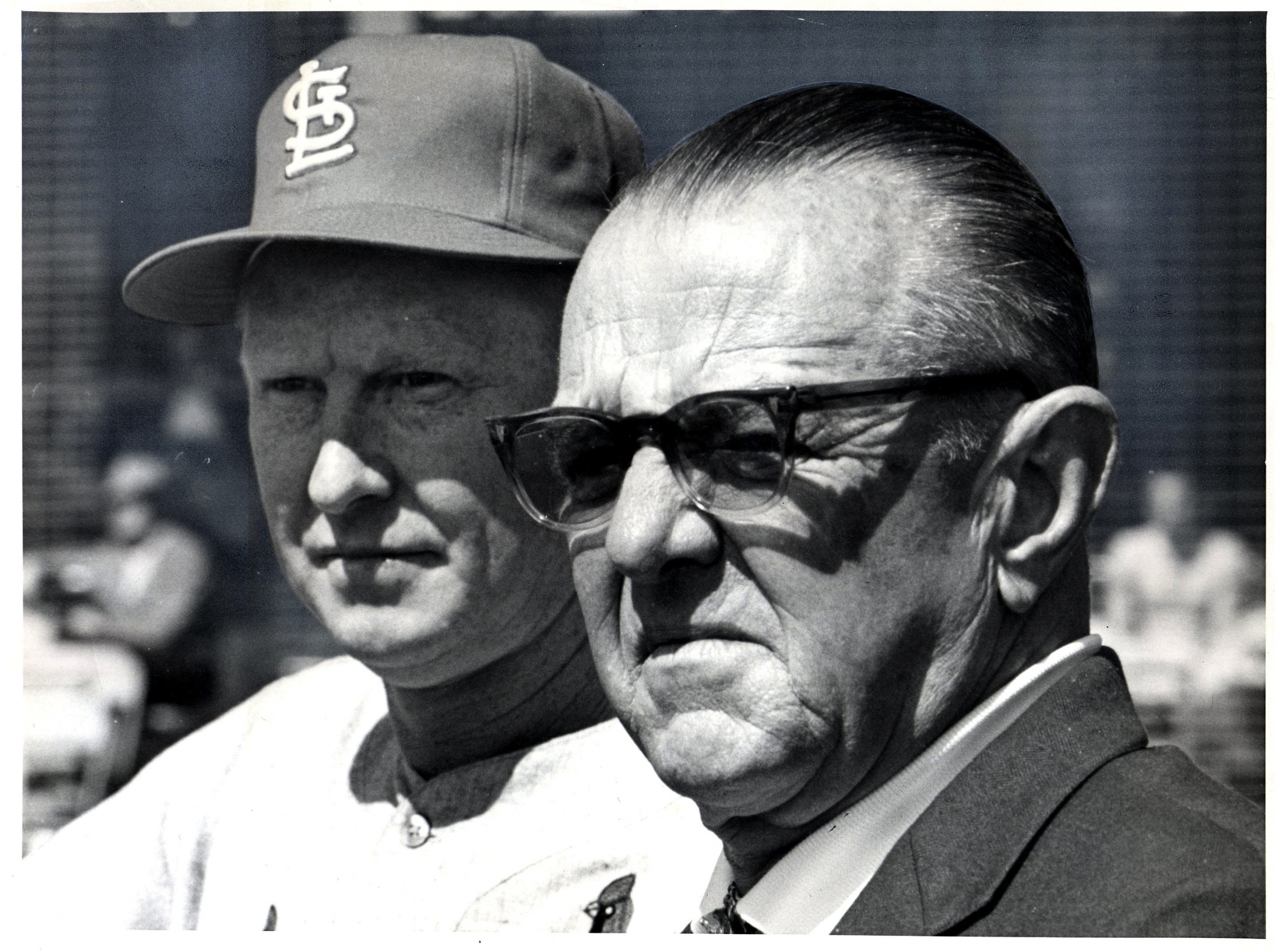

Gussie Busch

For nearly a quarter century, Gussie Busch simultaneously led a nationwide brewing company and the St. Louis Cardinal franchise. Nicknamed “The Big Eagle”, Gussie lived life to its fullest. His enemies called him profane, tyrannical, hot-tempered, a philanderer, and a huckster. His friends saw him as soft-hearted, congenial, open, personable, philanthropic, and loyal.

For nearly a quarter century, Gussie Busch simultaneously led a nationwide brewing company and the St. Louis Cardinal franchise. Nicknamed “The Big Eagle”, Gussie lived life to its fullest. His enemies called him profane, tyrannical, hot-tempered, a philanderer, and a huckster. His friends saw him as soft-hearted, congenial, open, personable, philanthropic, and loyal.

In 1953, he convinced his brewery, Anheuser-Busch, to buy the financially struggling St. Louis Cardinals.1 After 11 years of frustration, Busch won his first World Championship with the 1964 Cardinals. Starting in 1964, Gussie subsequently left a baseball legacy of six National League Champions and three World Series winners.

Born in St. Louis on March 28, 1899, August Anheuser Busch Jr. was the second son of August A. Busch Sr. and the former Alice Ziesemann Already immensely wealthy, Gussie’s family also included five sisters. His grandfather Adolphus Busch Sr. co-founded the Anheuser-Busch brewery and became a legendary figure in St. Louis.

Gussie idolized his highly successful grandfather. Adolphus set the standard for the legendary Busch family work ethic. He once described the secret of his success as a willingness “to work double the time I was paid for.”2

In 1903, Gussie’s father acquired the 245-acre Grant’s Farm in South St. Louis County, and later built a hunting lodge and a French chateau on the property, and moved his family to the country. The chateau had 26 rooms and 14 baths. The farm subsequently grew to 281-acres and was opened to the public in 1955 featuring a menagerie of exotic animals, including the famous Clydesdales. Gussie transformed this tract into a very popular tourist attraction to craft the image of his brewery.

Young Gussie spent his youth learning to ride, shoot, and enjoy the life of wealth provided by his doting parents. He also drove horse coaches competitively and enjoyed both horse riding and boxing. He traveled extensively, accompanying his grandfather on several trips to Germany. For a brief time, he tried rodeo-riding in Wyoming where he met Will Rodgers. As later reported in Time magazine, Busch remembered, “a kid just couldn’t have had more.”3

Although he subsequently gave millions to various educational institutions and received honorary degrees from several universities, Gussie initially shunned formal education. He attended the public Tremont School in St. Louis and the private Smith Academy but never graduated from high school. “Without a doubt,” Busch later remembered, “I was the world’s lousiest student. I never graduated from anything.” 4

During World War I, Busch served for 14 months as a “stable sergeant” For the Home Guard. In 1918, he married the beautiful 22-year-old Marie Christy Church. She bore Gussie two daughters before dying of pneumonia in 1930.

Busch started his working life in a family-owned bank and then moved on to a railroad company where the family owned a significant share of the stock. At age 24, he started working in the brewery. He began at the very bottom, initially scrubbing beer vats and performing menial tasks throughout all of the brewery’s operations. His dad subsequently appointed him the general superintendent of brewing operations.5

As would be expected, the advent of prohibition devastated the legal brewing industry. The Busch family faced a decision. They could go out of business and sell their $30,000,000 brewery for scrap. At ten cents on the dollar, the family could retire from the brewing business and still walk away with a sizable amount of money.

Instead, they doggedly kept turning out other products such as baker’s yeast, malt syrup, and grape-flavored pop to try to keep the operation open. They achieved only limited success. As a last resort, his dad sent Gussie to meet with gangster Al Capone. They reached a deal where Busch would legally supply Capone with the raw ingredients for his illegal brewing operations.

Gussie later recalled, “We ended up as the biggest bootlegging supply house in the United States. Every goddamn thing you could think of. Oh, the malt syrup cookies! You could no more eat the malt syrup cookies… They were so bitter ….It damn near broke Daddy’s heart.”6

When Prohibition ended at midnight on April 6, 1933, the brewery gates swung open and the big brewery trucks rolled though the St. Louis streets delivering the beer to a thirsty public. The Saturday Evening Post subsequently reported Gussie’s reaction: “It was the greatest moment in my life,” he said. “The greatest, I guess that I will ever know.”7

In September 1933, Gussie married his second wife Elizabeth Overton Dozier. The two apparently had an affair before the death of his first wife and the marriage occurred only two weeks after Elizabeth’s divorce from her husband. She subsequently bore Gussie both a daughter and a son.

Less than a year later, the Busch family suffered a significant setback as August A. Busch Sr. died in February 1934. Mr. Busch, who was 68 years old, suffered intense pain for over six weeks from a complication of heart disease, gout, and dropsy. During his painful ordeal, Gussie reportedly tried to cheer him up by riding a horse into the house and up a staircase to his father’s second-floor bedroom. 8

His recovery efforts did not result in any significant improvements. Using a revolver he kept by his bedside, he killed himself with one shot under his heart. Busch left an unsigned note on a night table beside his bed. On a plain sheet of paper it read, “Good-bye, precious mommy and adorable children.” In the tradition of the Busch family, the presidency of the brewery passed on to the eldest son, Adolphus.9

The 43–year-old Gussie volunteered for service in the Army in June 1942 and received the rank of lieutenant colonel with an assignment to the Pentagon. He oversaw ammunition production, won promotion to colonel in 1944, and received the Legion of Merit for his service.10 Throughout his time in the Army, he continued to add to his reputation as someone who liked to party and flirt with the girls. Remembering his military experience, Gussie later confided, “Jack Pickens (an old friend) was in the service with me. We used to smell powder together—that is women’s face powder.” When Adolphus died on August 29, 1946, Gussie became president of the company.11

Returning home after his service, Busch also found that all was not well between him and his second wife. A lady of queenly disposition, Elizabeth did not share his love of hops, horses, hunting, and singing German party songs. Busch quickly moved out of the family’s town house back to Grant’s Farm. Instead of living in the main mansion (his mother still used the residence), he moved into a nearby 18-room apartment. Gussie dealt with his loneliness by hosting spectacular parties.12

On a subsequent trip to Switzerland in 1949, Busch met the beautiful 22-year-old Gertrude (Trudy) Buholzer. After a nasty $1,000,000 divorce settlement with Elizabeth, he married Trudy in 1952 at the Busch family cottage in Little Rock, Arkansas. Trudy bore him seven children between 1954 and 1966.13

In February1953, Fred Saigh, the Cardinals owner, faced a prison sentence for tax evasion. Rumors flew that out-of-towners would buy the team and move it to Milwaukee. Busch and his brewery stepped in, bought the struggling team for $3.75 million, and pledged never to move the team out of St. Louis. At the time of the sale’s announcement, Busch vowed, “Come hell or high water, I will bring a baseball World Championship to St. Louis before I die.”14

The local press lauded him as the savior of the team. However, the primary reason for buying the team was to sell more beer. The Cardinals and Anheuser-Busch quickly became enmeshed. From a personal viewpoint, after saving the Cardinals, the flamboyant Busch family also finally gained full access to the upper echelon of St. Louis society.15

Gussie soon discovered he was now a national personality. On a trip to New York, shortly after buying the club, Busch decided to meet baseball reporters at a luxurious restaurant. Anticipating a small group would attend, a stunned Busch ended up meeting over 300 baseball journalists. He never forgot the incident. The volume of his incoming mail also skyrocketed. Busch marveled, “Not many people wrote to me when I was just a brewery president, but as owner of the Cardinals…I began to receive thousands of letters.”16

Busch quickly found he had several formidable obstacles to overcome before the brewery would reap the enormous potential of his acquisition. Including the team’s initial selling price, the brewery poured an estimated $6 to 7 million dollars into the Cardinals franchise. It bought and completely refurbished the dilapidated stadium where the ball club played (Sportsman’s Park).

Initially, Busch also attempted to rename the ballpark Budweiser Stadium. However, Commissioner Ford Frick would not approve the name due to the commercialization of a product. In memory of his grandfather, father, and brother, Gussie adjusted it to Busch Stadium. Then, he ordered his brewery to create a new line of beer with Busch on the label. He also began to restore the Cardinals’ withering farm system.

Busch wanted to quickly make the team competitive. Not surprisingly, his initial baseball personnel decisions tried to both improve the Cardinals and sell more beer. Essentially, he tried to buy a pennant by throwing money at the other owners to obtain stars like Willie Mays, Ernie Banks, and Gil Hodges. The other owners successfully rebuffed his efforts, forcing Busch to make a number of embarrassing efforts to purchase overrated players.17

In early 1953, Busch went to his first Cardinals spring training camp in St. Petersburg, Florida. He arrived at the wheel of his specially outfitted bus. Costing $75,000, the bus had an Anheuser-Busch emblem on the back. Inside, it had six berths, a galley, a bar, a bathroom, and a lounge. 18 He mingled with his new team even donning his own Cardinals uniform. Although his trip generated nationwide publicity for the brewery, the 1953 Cardinals finished third.

The brassy Busch approach of simultaneously promoting beer and professional baseball angered some in Congress. Sen. Edward Johnson from Colorado sponsored a bill that made baseball clubs owned by beer or liquor subject to antitrust laws. In addition, he called Busch “a personable and able huckster” who regarded baseball as “a cold-blooded, beer-peddling business.” Gussie subsequently testified successfully before the Senate Judiciary committee against Johnson’s bill. The bill went nowhere.19

In 1954, Busch, with his characteristic flourish, updated his transportation to Cardinal road games. The Wabash Railroad delivered a $300,000 custom built “rail business car” to Gussie. Busch named the 88-foot streamlined car the Adolphus. The exterior of the stainless steel car featured a St. Louis Cardinal emblem on one end and an Anheuser-Busch emblem on the other. Inside accommodations included four bedrooms which could be converted into meeting rooms, a dining room, two bathrooms with showers, two service personnel quarters, and an observation lounge fully stocked with Anheuser-Busch beer20.

Sometimes, Busch attached the luxurious Adolphus to the train that carried the Cardinals on their road trips. As the Cardinals reached their destinations, Busch could and did use the car to hold meetings with his beer wholesalers and retailers in the area. When Gussie traveled with the team, his parties featured gin playing (Busch’s favorite card game) and heavy drinking. In 1955, he spent nearly the entire year traveling the country on the Adolphus meeting with the brewery’s 900 wholesalers.21 Impatient for success, Busch employed five managers between 1953 and 1959—Eddie Stanky, Harry Walker, Fred Hutchinson, Stan Hack, and Solly Hemus. During the same period he employed three general managers: Dick Meyer (a brewery executive), Frank Lane, and Bing Devine. The changes made no difference. After the 1953 third-place finish, the team finished in the second division four times through 1959. In January 1958, Musial agreed to a salary of $91,000; but Busch increased the pact to make Stan the first $100,000 per year NL player.

In the early 1960s, GM Devine began accumulating a group of young, talented black players who would form the strong nucleus for several future winning teams. For many years, the Cardinals held their spring training in St. Petersburg, Florida. Reflecting the local social norms of the times, St. Petersburg discouraged racial interaction. Black players stayed in different quarters than the whites. Those whites who did not agree with the practice rented private houses.

Cardinals first baseman Bill White publicly criticized the situation and both the Cardinals and the brewery issued statements denouncing the practice. Busch bluntly told local officials to fix it or the team would train at some other site.

Local officials quickly found a way to lodge the entire team together. Several of the white players had traditionally stayed with their families in beachfront cottages during spring training, but when Musial and Boyer gave up their private accommodations to move in with the rest of the team—blacks included—the Cardinals successfully broke down the local custom. The Cardinals motel became a tourist attraction. People would drive by to see the white and black families swimming together or one of the famous team barbecues, with Howie Pollet making the salad and Boyer, Larry Jackson, and Harry Walker grilling up the steaks and hamburgers. As Bob Gibson later remembered, “The camaraderie on the Cardinals was practically revolutionary in the way it cut across racist lines.” Busch’s strong show of support for equality within the entire team created the environment necessary for future Cardinals successes.22

During the 1963 season, Cardinals icon Stan Musial announced he would retire at the end of the season. In addition, under Devine’s and Johnny Keane’s leadership, the Cardinals were now serious contenders. Busch wanted an NL pennant for both himself and Stan, the man who remained steadfastly loyal to him throughout his ownership. The 1963 Cardinals won 93 games but Sandy Koufax and the Los Angeles Dodgers won the pennant. After the season, The Sporting News recognized Devine’s efforts by naming him their NL Executive of the Year.

After the profoundly discouraging near-miss finish in 1963, a volatile Busch demanded a pennant in 1964. He publicly threatened to tear down the current Cardinal management structure and start over again. Branch Rickey, who Busch hired as a special consultant in October 1962, encouraged him. Engaged in a behind-the-scenes power struggle with Devine, Branch wanted to bring in his own GM.

Throughout his career, Busch would never accept dishonesty or disloyalty from any of his employees. During the 1964 pennant race, he sincerely believed Devine both lied and betrayed him by not telling him about a disagreement within the team. When he felt Devine subsequently covered up the incident, he impulsively fired both Devine and their long time business manager, Art Routzong. Privately, he also made plans to fire manager Johnny Keane. At Rickey’s recommendation, Bob Howsam became the new Cardinals GM.23

Amidst all the management upheavals, the 1964 Cardinals unexpectedly rallied in September. The pennant race came down to the last game of the season. When St. Louis fell behind early, Busch left his seat and went up to his private box called the Redbird Roost. Angry and frustrated the team might again come close and lose again, Busch kicked a hole in the wall of the Roost. 24 The team rallied, beat the Mets, and won the 1964 NL pennant by one game over Philadelphia and Cincinnati. After the game, a beaming Busch could hardly contain himself as he walked around the clubhouse hugging the ballplayers. The Cardinals went on to beat the Yankees in the 1964 World Series. In a final irony, The Sporting News again named the fired Devine their NL Executive of the Year.25 Then, at an October 16 press conference to publicly offer a new contract to Keane, Johnny presented Gussie with his resignation letter dated September 28. The Cardinals quickly selected Red Schoendienst as their new manager.

In addition to bringing a world championship to St. Louis, Busch led a drive to replace his refurbished old stadium with a privately-funded new one. On May 12, 1966, the new Busch Memorial Stadium opened in downtown St. Louis. The stadium led to a revitalization of the entire area. The new stadium became the last major sports complex to be built solely with private funds.

By the end of 1966, with Howsam’s help, a strong restructured Cardinals team emerged. Howsam then left St. Louis for an offer from Cincinnati. In January 1967, the loyal Busch again reached out to his long-time friend, Stan Musial, and persuaded him to become the new Cardinals GM. This action brought Schoendienst and Musial together again.

The 1967 Cardinals won both the NL pennant and the subsequent World Series against the Red Sox. Orlando Cepeda, a May 1966 Howsam acquisition, won the NL Most Valuable Player Award. The Cardinals also went over two million in home attendance for the first time.

Off the field, Busch continued to party hard during the 1967 World Series. He, his wife, and a group of close friends thoroughly enjoyed themselves when they traveled to root for the Cardinals in Boston. At one Boston hotel, their food fights and chandelier-swinging mayhem caused an estimated $50,000 worth of party-related damages. When presented with the bills, Busch reportedly told his employees to put the expenses in the advertising account.26

In November 1967, Stan Musial, who was never really comfortable behind a desk, told Busch he no longer wanted to be the Cardinals GM. Surprisingly, Busch rehired Bing Devine. He publicly admitted he had made a mistake in letting Devine go in 1964. He attributed his mistake to “impatience and misunderstanding.”27

The Cardinals easily won the 1968 NL pennant as Bob Gibson was the NL Most Valuable Player and Cy Young award winner. After leading three games to one, the team faltered in the World Series losing to the Detroit Tigers.

The 1960s teams won three championships and Busch rewarded them handsomely. By 1970, Busch became the first team owner in history to have a payroll in excess of one million dollars.28

However, Busch and his Cardinals fell on hard times starting in 1969. Much to his chagrin, Gussie found his paternalistic approach toward player relations now publicly portrayed as one-sided and akin to slavery. Curt Flood’s vocal support of these positions and his public salary squabble with the club irked Busch. Right or wrong, Busch sincerely believed he saved Flood from baseball oblivion earlier in his career. He now felt Flood had betrayed his loyalty. The Cardinals’ subsequent trade of Flood to Philadelphia prompted Curt to declare himself a free agent. 29

Near the end of 1974, Busch and Trudy tragically lost their youngest daughter, Christina Martina Busch. Described as a “beautiful blue-eyed blonde child,” and nicknamed “Honey Bee” by Busch, Christina died on December 17 from injuries she suffered in a December 6 traffic accident while returning from school. The crash, on a busy St. Louis expressway, killed their chauffeur instantly. The other passenger in the Volkswagen bus, her brother Andrew, survived. The loss deeply affected both Gussie and Trudy.

In 1975, his son Augustus Busch III successfully convinced the Anheuser-Busch Board of Directors to force his 76-year-old father’s retirement as the head of the company. He relinquished day-to-day brewery control, becoming an honorary Chairman of the Board of Directors. As a part of the deal, he retained control of the Cardinals.30

In 1978, frustrated by nearly ten years without a pennant-winning ball club and going through a messy divorce with Trudy, Busch fired Bing Devine a second time. He also employed three field managers that season: Vern Rapp, Jack Krol, and 1964 (NL) MVP Ken Boyer.

In 1980, after an unsuccessful decade, Busch made another outstanding baseball decision by hiring Whitey Herzog as both his GM and on-the-field manager. Busch and Herzog clicked immediately. Both Whitey and Gussie shared German ancestry and loved beer. Whitey enjoyed a direct line of communication with Busch. For his part, Busch later said, “He’s (Whitey) not only a great manager but a helluva guy. He and I talk the same language.” In his 11 years with the team, the Whitey-led Cardinals won one World Championship and three NL championships.31 In 1987, the Cardinals went over the three million mark in home attendance for the first time. Busch also started a new St. Louis postseason tradition before each NLCS and World Series home games during the 1980s when he would ride into Busch Stadium on the Budweiser Clydesdales wagon waving a red cowboy hat. The Cardinal fans went wild and Gussie loved the attention.

In 1981, Gussie married Margaret Snyder, his onetime personal secretary. Six years before, she became the first woman to serve on the board of directors of Anheuser-Busch. In the same year, the St. Louis Cardinals also named her to its board. In August 1988, she suffered a pulmonary embolism and died at the age of 72 in a St. Louis hospital.

In 1982, Busch reportedly played a key role in the dismissal of then Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn. At various times during Kuhn’s tenure, Busch publicly clashed with him over a variety of baseball and business issues. Ultimately, Busch sided with just enough other owners to deny Kuhn’s continuation as the commissioner.32

In 1984, the Cardinals retired the number 85 in honor of Busch’s 85th birthday.

In 1989, after a hospitalization for pneumonia, the 90-year-old August A. Busch Jr. died at his St. Louis home. A sister, one former wife, nine children, 27 grandchildren, and nine great-grandchildren survived him.

When asked if he ever regretted his baseball ownership experience, Busch replied, “Hell, I’d do it all over again.”33

This biography is included in the book “Drama and Pride in the Gateway City: The 1964 St. Louis Cardinals” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by John Harry Stahl and Bill Nowlin. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Last revised: September 10, 2023 (zp)

Notes

1 Christensen, Lawrence O., Foley, William E., Winn, Kenneth H., Dictionary of Missouri Biography, (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1999), “Busch, August A. Jr., (1899-1989)”, 138.

2 National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Busch Clippings File as of July 2010, Time Magazine, July 11, 1953. , 85

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Malone, Roy, “Gussie Busch: Soft Heart With a Hard Nose,” The St. Louis Post Dispatch, August 25, 1975, p.13A and Kester, William H., “Gussie, ‘The Boss,’ Built An Empire With His Beer,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 27, 1975, 4G

6 Golenbock, Peter, The Spirit of St. Louis, A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (New York: Harper Entertainment, 2000), 403

7 Martin, Harold H. “The Cardinals Strike It Rich” The Saturday Evening Post, June 27, 1953

8 Thomas Jr. Robert McG., “August A. Busch Jr., Dies at 90; Built Largest Brewing Company,” Obituaries, The New York Times, September 30, 1989

9 Golenbock, op. cit., 404

10 Boxerman, Benita W and Boxerman, Burton A, Ebbets to Veeck to Busch, Eight Owners that Shaped Baseball (Jefferson NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, 2003), 179

11 Golenbock, op. cit.

12 Martin, op. cit.

13 Ibid.

14 Thomas Jr., op. cit.

15 Golenbock, op. cit., 405

16 Hernon, Peter and Ganey, Peter, Under the Influence – The Unauthorized Story of the Anheuser-Busch Dynasty (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991), 215

17 Koppett, Leonard, “Busch, Beer and Baseball”, New York Times, April 11, 1965

18 Hall of Fame Busch clippings file Gardner, John, “Gussie’s no Buscher”, April 21, 1954 and Martin, op. cit., 23 and 70

19 Herman, op. cit., 213, and “Busch Rejects Charges by Sen. Johnson That Cards Are Used to help Beer Sales,” New York Times, February 24, 1954

20 Hall of Fame Busch clippings file “$300,000 Rail Business Car for Card President Busch,” January 12, 1955

21 Kester, William H., “Gussie, ‘The Boss,’ Built An Empire With His Beer, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 27, 1975, 4G and Hernon, op. cit., 216

22 Golenbock, op. cit., 440-441

23 Broeg, Bob, “The ‘Big Eagle’ Never Was Able To Buy A Pennant”, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 29, 1975, 5B

24 Malone, Roy, “Busches: “Too Flamboyant! For St. Louis High Society,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 26, 1975, 10A

25 Wilks, Ed., “Devine Acclaimed as Executive of the Year,” Sporting News, October 24, 1964, 1

26 Hernon and Ganey, op. cit., 249

27 Malone and Kester, op. cit.

28 Broeg, op. cit.

29 Boxerman and Boxerman, op. cit., 506 & 507

30 Schafers, Ted, “Grand old man of brewing steps aside as chief executive”, St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 9, 1975 and Boxerman and Boxerman, op. cit., 195

31 Golenbock, op. cit., 528

32 Martin, op. cit., 200-202

33 Malone, op. cit.

Full Name

August A. Busch

Born

March 28, 1899 at St. Louis, MO (US)

Died

September 29, 1989 at St. Louis, MO (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.