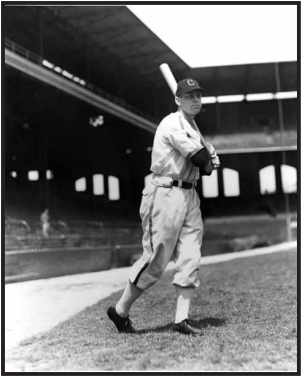

Guy Curtright

Guy Curtright didn’t reach the major leagues until he was 30 years old, but when he finally got a chance with the Chicago White Sox in 1943, he broke in with a bang. In his debut season Curtright hit safely in 26 straight games – an American League rookie record that wasn’t broken until 1997 – and was leading the league in hitting in late July. Though he never reached such heights again, Curtright wound up playing four seasons with the White Sox, compiling a .276 lifetime mark that was 21 points higher than the overall American League average for 1943-46 seasons. Then Curtright, who had begun working as an offseason sports coach and math teacher as a minor leaguer in the 1930s, continued to make his mark as a coach and athletic director at two Chicago-area high schools for another quarter of a century.1

Guy Paxton Curtright was born on October 18, 1912, in Holliday, Missouri, a tiny village (population 137, according to the 2010 US Census) in Monroe County, about 150 miles northwest of St. Louis. His father, Elwood Elmo Curtright, had been born in Monroe County in 1888 and married his mother, the former Madge Cunningham, in 1910. Elwood Curtright worked as a rural mail carrier, and Guy’s son Mickey fondly remembered riding with his grandfather on his mail route.2 Guy was the oldest of four children.3 The 1946 Baseball Register listed his nationality as English-Irish and said that he had blue eyes and blond hair.4

After graduating from high school in Monroe County, Curtright attended Northeast Missouri State Teachers College (now known as Truman State University5) in Kirksville. While there he played baseball, football, and basketball and also ran the 100-yard dash on the track team, earning four letters. (According to Mickey Curtright, the first football game on an organized level that Guy ever saw was one that he played in.6) Guy, who was listed at 200 pounds during his major-league career, played guard on the Northeast Missouri State football team under coach Don Faurot, who later went on to fame as the head football coach at the University of Missouri. The Bulldogs won 26 straight games under Faurot from 1932 to 1934, and Curtright, who earned all-conference honors for his guard play, was credited with a key block that sprang quarterback Arnold Embree for a 40-yard touchdown run against Southeast Missouri State during the win streak.7

Curtright graduated with a bachelor of science degree in 1934, and that year he began his professional baseball career, playing in 23 games with Sioux City (Iowa) of the Class-A Western League (hitting .244) and 59 games with Muskogee (Oklahoma) of the Class-C Western Association (hitting .291). On September 28 of that year he married Edna Ruth Davis, a 22-year-old native of Denver who was visiting relatives in Missouri. The Curtrights remained married for nearly 63 years until Guy’s death in 1997, and the couple produced three sons: Jerry (born in 1937), Mickey (1939), and Don (1944).8 To complete a busy 1934, Curtright began working at Wellsville (Missouri) High School that fall as a mathematics teacher, physical-education instructor, and football and basketball coach. He was credited with introducing football to Wellsville High, and according to the Moberly (Missouri) Monitor-Index, Curtright’s football teams “compiled a fine record. His basketball teams were even more successful.”9

The Muskogee team that Curtright had played for in 1934 was affiliated with the Detroit Tigers,10 and Guy began the 1935 season with another Tigers farm club, the Henderson (Texas) Oilers of the Class-C West Dixie League (renamed the East Texas League in 1936). Except for a 10-game stint with Charleston of the Mid-Atlantic League in 1937, Curtright remained with the Oilers until midseason 1939. Playing center field,11 the right-handed-hitting Curtright batted .310 or higher during each of his years with Henderson, had seasons with18 and 19 home runs, and displayed excellent speed: The Spalding Baseball Guides of the era credited him with 190 stolen bases over that five-year period, including a league-leading 50 steals in 1936. In the meantime he continued to coach and teach during the offseason, leaving Wellsville High to coach basketball at Central Wesleyan College in Warrenton, Missouri, and then serving as football and basketball coach at Henderson High School in the city where he was playing minor-league ball.12

In July of 1939, Curtright finally got a promotion when his contract was sold to the Shreveport (Louisiana) Sports of the Class-A1 Texas League.13 Shreveport was a farm club of the Chicago White Sox in 1939, and Curtright’s contract was now under control of the White Sox. However, after he finished the ’39 season with a .324 average in 46 games with the Sports, Curtright was one of 91 minor-league players declared free agents by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis as a result of improper handling while Guy was a Tigers farmhand. Curtright, though, informed the commissioner that he wanted to remain with Shreveport, and Landis acceded to his request.14

Curtright played for Shreveport (which was now no longer a White Sox farm club) in 1940 and ’41, and for the first time since 1934, he failed to hit over .300, posting averages of .261 and .291. In 1942 he moved up to the Double-A St. Paul Saints of the American Association, hitting .291 with 13 homers in 103 games. His offseason work included studying for his master’s degree in education from the University of Missouri (where he also worked as an assistant football coach under Don Faurot in 1941), and then a position as athletic director and football, basketball, and track coach at Mexico (Missouri) High School beginning in February of 1942.15

By the end of the 1942 season, Curtright had played in more than 1,000 minor-league games and displayed both speed and power while compiling a career batting average of over .300 – but he’d never received a chance to play major-league ball. However, with World War II raging and many major leaguers being called into military service, the landscape had changed, and new opportunities were available even for older minor leaguers like Curtright, who would turn 30 on October 12. He finally got the call that autumn when St. Paul sold his contract to the White Sox.16

Because of wartime travel restrictions the White Sox were training in French Lick, Indiana, in the spring of 1943, and a Chicago Tribune story on March 3 stated that White Sox manager Jimmy Dykes was looking for a right-handed-hitting outfielder … but then added, “Guy Curtright is a right hander but at present is wandering about Missouri with a basketball team he coaches.”17 Curtright, who according to his son Mickey was usually given permission to report late to spring training in order to wrap up his high-school coaching duties, eventually arrived and made enough of an impression to be the subject of a Tribune feature story in early April.18 He made the team’s Opening Day roster, but his early-season appearances were limited to pinch-hitting or pinch-running. He finally received his first start in a 1-0 victory over the Detroit Tigers at Comiskey Park on May 7, going 0-for-1 while drawing three walks. But after a couple more starts, Curtright was back on the bench again.

It wasn’t until Memorial Day, May 30, that Curtright finally got a chance to play regularly. He soon made the most of it. Beginning on June 6 at Boston’s Fenway Park, he put together a 26-game hitting streak that set an American League rookie record and was only one game short of the all-time major-league rookie mark set by Jimmy Williams of the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1899.19 Curtright’s American League mark would last until 1997, when Nomar Garciaparra of the Boston Red Sox hit safely in 30 straight games.20 The streak finally ended on July 2, when Curtright went 0-for-4 in a 3-2 loss to the Washington Senators at Comiskey Park. The hot streak lifted his batting average, which had stood at .167 when he began playing regularly, into the American League lead with an average that peaked at .368 after the games of June 27. Though his average would begin to tumble after that, he was leading the AL in hitting as late as July 22.

Curtright was modest about his success, telling the Associated Press, “I’ve been getting the breaks. Every time I’ve hit the ball hard it’s been right in there, between the fielders.”21 The latter stages of the season proved more of a struggle for Curtright and included a beaning by Alex Carrasquel of the Washington Senators at Griffith Stadium on July 28 – resulting in a trip to Georgetown Hospital22 and several days back home in Missouri while recuperating.23 By season’s end, Curtright’s average had dropped to .291, a figure that still ranked sixth in the league among players with 400 or more at-bats. The rookie had played in 138 games and contributed to the success of a White Sox team that finished fourth in the American League with 82 wins, 16 more than the club had compiled in 1942.

Curtright returned to the White Sox in 1944 and was in the club’s Opening Day lineup in right field against the Indians, but he eventually lost his starting job and finished the year with a .253 average in 72 games (including 47 starts). He had a better year in 1945, hitting .281 in 98 games (with 81 starts in the outfield). But by the end of the season World War II was over, and with prewar veterans returning to the major-league ranks for the 1946 season, the best the 33-year-old Curtright could do that spring was to make the White Sox roster as a spare outfielder.

After seeing sporadic action in the first three months of the season, Curtright played his final major-league game on July 18, 1946, when he went 0-for-3 in a 3-2 White Sox loss at Boston’s Fenway Park. His .200 batting average in 55 at-bats that year dropped his lifetime average to .276 with a .363 on-base percentage, figures that were comfortably above average for the period. Curtright’s career OPS+, a stat that compares a player’s on-base percentage plus slugging percentage to the league norm with an adjustment for ballpark factors, was 115, or 15 percent above average for the American League, from 1943 through 1946.

Released by the White Sox after the 1946 season, Curtright wasn’t quite done with professional baseball; he returned to Shreveport of the Texas League in 1947, hitting .229 in 73 games before finally retiring from the game. But he wasn’t retiring from sports. In the fall of 1946 Curtright landed a job as athletic director and baseball, football, and basketball coach at Woodstock High School in suburban Chicago, and he was finally ready to make coaching his full-time profession. He was taking on a challenge, particularly on the gridiron: the Woodstock football team had not only gone winless the year before Curtright took over; it had failed to score a single point.24

For the next 26 years Curtright coached in the Chicago suburban area, first at Woodstock High and then as the first athletic director and baseball coach at North Chicago High beginning in 1954.25 His only nonsports venture was brief: Mickey Curtright said that between the two coaching stints, Guy and a friend invested some money in a milk-delivery business, until one hot day when the wax-coated milk containers melted in the heat of their nonrefrigerated truck. That was enough to convince Guy to return to coaching.26

Curtright was a very successful coach. G.A. McElroy of the (Chicago) Daily Herald wrote that “Wherever Guy has coached, the schools have won championships. Most recently he took over cellar dwelling Woodstock and won two football championships and three straight baseball titles” as well as a basketball team that won 26 straight games. His North Chicago baseball team reached the finals of the state baseball tournament in 1955, Guy’s first year on the job, before losing the championship game to Schurz of Chicago, 2-1.27

Among Curtwright’s players during his Chicago-area coaching tenure were each of his three sons. Jerry, the oldest, played football and baseball for Guy at Woodstock before lettering in football and baseball at the University of Missouri; Mickey played three years of baseball at North Chicago; and Don played four years of baseball at North Chicago.28 Don Curtright was also a star football player at North Chicago High; he went on to play football at the University of Miami in Florida and earned a free-agent trial with the Denver Broncos.29 All three Curtright sons also coached high-school sports at some point during their lives – most notably Jerry, who coached football, baseball, and golf during a 25-year career at Dundee (Illinois) and Dundee-Crown High Schools. Among Jerry Curtright’s players during his coaching career was future major leaguer Juan Acevedo, whom Jerry was credited with helping develop as a pitcher. (Jerry Curtright passed away in January of 2013.)30

After retiring as athletic director at North Chicago High in 1972, Guy moved to Colorado for a few years and eventually settled in Florida. He died in Sun City Center, Florida, on August 23, 1997, at the age of 84 after complications from hip surgery. He is buried (following cremation) at Shepherd of The Hills Presbyterian Church Cemetery in Lakewood, Colorado.

Two days after Guy’s death, Nomar Garciaparra broke Curtright’s 54-year-old record for the longest hitting streak by an American League rookie; but record-holder or not, Guy Curtright would be fondly remembered as a coach, teacher, mentor, father – and ballplayer.

Notes

1 Telephone interview with Mickey Curtright, September 11, 2014.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Baseball Register, 1946 (St. Louis: C.C. Spink & Sons, 1946), 68.

5 truman.edu, “The History of Truman State University.”

6 Mickey Curtright interview.

7 “When Football Was Fun – Faurot Days in Kirksville,” Kansas City Times, October 15, 1974.

8 Baseball Register, 1946; Mickey Curtright interview .

9 “Guy Curtright is Going Strong in E. Texas League,” Moberly (Missouri) Monitor-Index, August 5, 1937.

10 Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball Third Edition (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 2007).

11 “Guy Curtright to Shreveport Club,” Moberly Monitor-Index, July 28, 1939.

12 ”Prof. Curtright Applies Higher Theory of Batting,” Chicago Tribune, April 8, 1943.

13 “Guy Curtright to Shreveport Club.”

14 ”Guy Curtright to Play with Shreveport,” Moberly Monitor-Index, January 25, 1940.

15 ”Prof. Curtright Applies Higher Theory of Batting”; “Guy Curtright to Mexico High,” Moberly Monitor-Index, February 19, 1942.

16 “Guy Curtright to White Sox,” Moberly Monitor-Index, September 12, 1942.

17 “Dykes Seeks More Power in Outfield,” Chicago Tribune, March 3, 1943.

18 ”Prof. Curtright Applies Higher Theory of Batting.”

19 “Santiago Sets Record,” Galveston Daily News, September 27, 1987.

20 “Garciapparra Rewarded With Big Boston Payday,” Chicago Tribune, March 11, 1998.

21 “Guy Curtright Stars for White Sox,” Moberly Monitor-Index, June 26, 1943.

22 “Sox Gain Tie for 2d; Beat Senators, 12-7,” Chicago Tribune, July 29, 1943.

23 “Guy Curtright Makes Visit Home After Beaning,” Moberly Monitor-Index, August 7, 1943.

24 “White Sox outfielder to coach Woodstock,” Arlington Heights Herald, September 13, 1946.

25 “Mac Says,” The Daily Herald, February 11, 1954.

26 Mickey Curtright interview.

27 “Along the State Baseball Trail,” Chicago Tribune, June 4, 1964.

28 Mickey Curtright interview.

29 “Signs With Denver,” Alton (Illinois) Evening Telegraph, June 2, 1966.

30 “Legendary Dundee-Crown coach Curtright was one of a kind,” The Daily Herald, January 24, 2013.

Full Name

Guy Paxton Curtright

Born

October 18, 1912 at Holliday, MO (USA)

Died

August 23, 1997 at Sun City Center, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.