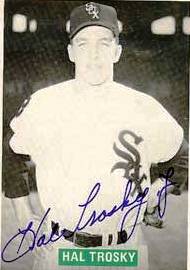

Hal Trosky Jr.

In 1961 Hal Trosky Jr., the son of a renowned major-league slugger of the 1930s, did something few aspiring ballplayers have ever done. A veteran of five minor-league seasons and a cup of coffee in the majors, he quit baseball cold turkey. No, he told the Chicago White Sox, he wasn’t returning their contracts unsigned, he just wanted his release. And at the age of 23, Trosky began to carve out a new career in the insurance business.

In 1961 Hal Trosky Jr., the son of a renowned major-league slugger of the 1930s, did something few aspiring ballplayers have ever done. A veteran of five minor-league seasons and a cup of coffee in the majors, he quit baseball cold turkey. No, he told the Chicago White Sox, he wasn’t returning their contracts unsigned, he just wanted his release. And at the age of 23, Trosky began to carve out a new career in the insurance business.

Harold Arthur Trosky Jr. was born on September 29, 1936, in Cleveland, two days after the end of a regular season in which his father had hit 42 home runs and led the American League with 162 runs batted in, He was the first of four children of Hal and Lorraine Trosky.

Within two weeks after young Harold was born, the family returned to their farm just south of Norway, Iowa, about 17 miles from Cedar Rapids. At the age of 4, in 1940, Hal entered the first grade at St. Michael’s Catholic school in Norway. Because the school year followed the farming calendar prevalent in the area, Hal was able to finish in time to return to Cleveland with his family in the spring.

There were no organized youth baseball programs in Noway at the time, but on almost every morning that snow didn’t cover the ground the younger boys would get together and play ball, and the games would continue until dark or dinnertime, whichever came first. Hal’s group of playmates included his cousin, future American Baseball Coaches Association Hall-of-Famer Harold “Pinky” Primrose. The number of players varied from day to day , and their rules might have to be adapted daily to accommodate the number of available players, but it was always baseball.

That languid lifestyle continued until the autumn of 1945, when the Troskys moved Hal to St. Patrick’s High School in Cedar Rapids, a short drive from the family farm. During his last year of high school, Hal also worked part time for the railroad as a laborer along with his cousin Pinky,, but he still found time to excel on the diamond for St. Patrick’s. Under head coach Joe Kenney, he never endured a losing season. As Hal’s hitting skill became more widely known, the number of scouts at his games grew. The Sporting News (June 9, 1954) reported that 12 major-league clubs were scouting Hal, attracted by his .667 batting average as a senior, his corner-infield skills, and his stellar performance as the top hitter on the Cedar Rapids American Legion team, a squad that had recently won the Iowa state title.

Hal began to receive offers from major-league teams. Hal Sr., who had spent some time as a scout for the White Sox, screened the various offers. According to The Sporting News, Hal Jr. told the local papers that he planned to attend Notre Dame in the fall unless there was an offer “too good to turn down.”

With so many interested scouts, and given his father’s baseball prominence, Hal had met various team executives during the recruiting process, He instantly liked Charlie Comiskey Jr., the White Sox owner, and in 1954 he signed a contract with White Sox scout Johnny Mostil. The White Sox sent him to the Colorado Springs Sky Sox of the Class A Western League, where manager Eddie Stewart was to evaluate him for two weeks. After that, the organization told Hal, he would be placed at an appropriate level.

Manager Stewart put Trosky in the starting lineup right away, playing first base, and on June 22, 1954, he hit a home run in his first at-bat, Trosky recalled. In his second game he was hit on the left hand by a pitch and three fingers were broken. He spent three weeks on the disabled list.

After returning to the lineup Trosky kept his batting average at just over .300, until he was injured again, in a game in Denver. “I was doing the splits, fielding a throw. The runner, Rocky Ippolito, ran into my left hamstring and tore it up pretty badly,” he said. “The next day, after consulting with the White Sox, the general manager at Colorado Springs told me they wanted me to continue to play. I did, and by the end of the season my batting average dropped about 60 points.” By the end of his first year in professional baseball, his average had fallen to .252, but the 59 games only whetted Chicago’s appetite.

During the offseason, on Valentine’s Day 1955, Trosky married Ellen Mae Gibson in St. Patrick’s Church in Cedar Rapids. As his parents had, Hal and Ella Mae eventually had four children, two sons and two daughters. Trosky labored as a sheet-metal worker that first offseason, then earned his insurance license the following year.

The new husband opened 1955 with the Superior Blues of the Class C Northern League, and almost immediately he was injured. As he fielded a throw that was low and up the baseline, the runner came inside the line and ran into the forearm on his glove hand. The result was a quarter-sized bone chip on his left elbow that made him unable to flex his arm. After 40 games, his second season was over, and he returned to Iowa to rehabilitate the arm. His orthopedic physician advised Trosky that surgery might permanently restrict his arm movement, and instead recommended that he spend the offseason exercising daily with a five-gallon bucket of sand.

Trosky was disciplined in his therapy. By the first day of 1956 spring training he had regained more than 90 percent of his flexibility and range of motion. He was invited to spring training with the White Sox, and though he was batting .345, a coach approached him one morning. “Have you ever thought about pitching?” the coach asked. “We think that the little restriction that you have remaining in your left arm will keep you from hitting big-league pitching. But we’ve noticed that everything you throw has natural movement on it and we want you to try pitching.” Trosky was 6-feet-3 and weighed 205 pounds, so size was not an issue for the White Sox.

Hal’s father had advised him to try anything the big-league club suggested, within reason, so he worked as a pitcher the rest of the spring. When he returned to Superior, it was as a side-arm pitcher. But White Sox pitching coach Ray Berres told him that he’d never get big-league hitters out throwing side-arm. The right-handed-pitching Trosky changed to a three-quarter delivery and used his fastball and “nickle curve” (today called a slider) to earn nine wins and post a 3.95 earned-run average for Duluth-Superior in his first season on the mound. (At that point, Hal’s career was a mirror image of his father’s: Hal Sr. had begun as a pitcher and moved to first base.)

In 1957 Trosky was promoted to the Davenport (Iowa) Davsox of the Class B Three-I League, and lowered his ERA to 3.66 while logging a 14-10 record. His progress was so dramatic that The Sporting News over the winter speculated that he might crack the Chicago pitching staff in 1958.

Trosky stayed with Chicago until the end of spring training in 1958, but the team (one year away from winning the American League pennant) had enough depth and assigned him to Indianapolis of the Triple-A American Association to start the season. After some organizational maneuvering, Hal found himself again playing with Colorado Springs in June. When the Sky Sox came to Des Moines for a series, Hal Sr. and Lorraine drove there from Cedar Rapids to spend a few days with their son.

Hal Trosky Sr. had been a legitimate star during his playing career, and had seen all types of pressure, both on and off the field, but he was unable to watch his son play once he turned professional. Hal Jr. (or Hoot Junior, as he was called in baseball circles) had pitched nine innings in the game before the team arrived in Des Moines, so the elder Troskys felt assured that they could visit without their son being at risk to pitch.

On Father’s Day 1958, Colorado Springs and Des Moines were halfway through a doubleheader when Hal and Lorraine decided to head back to Cedar Rapids in order to get home before dark. After their goodbyes, the Colorado Springs manager, Frank Scalzi, asked Hal if he could pitch the nightcap because the scheduled starter had injured himself while warming up. Trosky took the ball that afternoon and, while his parents were navigating State Route 30 back to Cedar Rapids, threw the only no-hitter of his life. His parents were thrilled when Hal called them that night, but Hal Sr. was still glad that he’d missed the stress of the game.

Hal posted a 13-9 record in the minors that year, and in September he was called up to the White Sox. He made his major-league debut on September 25, against the Detroit Tigers, when he relieved Dick Donovan in the fifth and pitched a scoreless inning. The White Sox won 7-1. Three days later, on the last day of the regular season, Trosky pitched two innings in relief against the Kansas City Athletics and got the victory, even though he gave up three runs. Those three innings pitched proved to be his entire major-league career.

His stint in the Kansas City game was a bit unusual. SABR member Norman Macht recounted it the Baseball Research Journal: After Trosky pitched a scoreless fifth inning, Chicago scored three in the last of the fifth and took a 6-1 lead. “Taking the mound for the sixth,” Macht wrote, “Trosky looked around his infield and took comfort from the steadying presence of [Nellie] Fox. Then a rare series of events occurred. Three ground balls were hit to Fox. Two went through his legs and one bounced off his chest. All three were scored as hits. Trosky walked a couple, and Suitcase Simpson, who had hit Trosky hard in the minors, roped one into center field for the only solid hit of the inning, and three runs were in. In the last of the sixth Jim Rivera batted for Trosky and struck out. Bob Shaw finished up. The win was credited to Trosky. He was twenty-two the next day. He never pitched another big-league inning.”

The next year, 1959 Trosky stayed with the White Sox until the final day of spring training, but was again sent to Indianapolis. After a 3-2 start, and pitching in eight straight games, he was sent to the Memphis Chickasaws of the Double-A Southern Association, playing for his father’s old teammate Luke Appling. Trosky said he had no idea why he was sent down, but the move proved providential.

Trosky had developed some calcification in his pitching shoulder, which may have prompted the transfer, but one night opposing coach Mel Parnell saw Trosky’s throwing motion and diagnosed him on the spot. Parnell, an outstanding left-handed pitcher for the Boston Red Sox in his day, had suffered the same malady and cured it with radiation treatments. He recommended the treatment to Hal. It included visiting a physician who happened to practice in Memphis. After a series of radiation treatments, the shoulder healed.

Now healthy, Trosky was recalled to Indianapolis over both his and manager Appling’s protests. Ellen was pregnant with son Gregg, so Hal drove the family back to Iowa and then flew out to join the team. The year finished without event, and the Troskys looked forward to 1960.

In the fall of 1959, Ellen became pregnant again, with daughter Tracy, and doctors discovered unexpected complications during a prenatal visit. There were blood compatibility issues between Ellen and her unborn child, so Hal remained home (without a contract) until he could be sure that both would be healthy. The clearance did not come until Tracy was born in late July. Except for a one-game stint with Nashville of the Southern Association, Hal’s chances had passed for the season.

While awaiting Tracy’s birth, Trosky played with Iowa Manufacturing in the local Manufacturers & Jobbers league in Cedar Rapids, so he was in shape for 1961, but when several contracts arrived from the White Sox, he returned them unsigned.

While Trosky was in Nashville, his manager, former New York Yankees pitching coach Jim Turner, had told him that he’d have been in the major leagues “two years ago” with any other team. That morsel of awareness, coupled with his own assessment and the fact that several other teams had been in contact with the White Sox seeking to acquire him, and that Chuck Comiskey no longer owned the team, had convinced Trosky that he had no future in Chicago.

The White Sox asked if his contracts were being returned due to a salary issue. No, Hal assured them, all he wanted was his release. “A year and a half later they were offered what I thought was a generous amount for me,” Hal told Norman Macht.. “They turned it down. Every spring for three years scouts came around and wanted to see me throw. They still wanted me. After that I’d been out too long. Physically I could come back but I couldn’t get mentally and emotionally ready again. I don’t know what the club’s thinking was. I guess somebody up there didn’t like me.” Eventually the team stopped sending contracts, but did not comply with Trosky’s request for a release for more than a decade, until 1972, after he had turned 36 years old.

Trosky had earned his insurance license in October 1955, and he had developed his clientele over each offseason since then. In 1961 he became a full-time insurance agent in Cedar Rapids, and worked for several firms over the years before opening his own agency in the 1980s. He still had the agency in 2010, despite devastating floods in the region in 2007 that erased more than 50 years of business and client records.

Last revised: September 10, 2021 (zp)

Sources

http://www.Baseball–reference.com

Harold Trosky, Jr., interview and e-mails (September 2010)

Macht, Norman L. “The 1.000 hitter and the undefeated pitcher.” Cleveland, Ohio: Baseball Research Journal, 1981.

Personal archives of Susan Volz

Cedar Rapids Gazette (various issues)

The Sporting News (various issues)

Full Name

Harold Arthur Trosky

Born

September 29, 1936 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

Died

November 23, 2012 at Hiawatha, IA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.