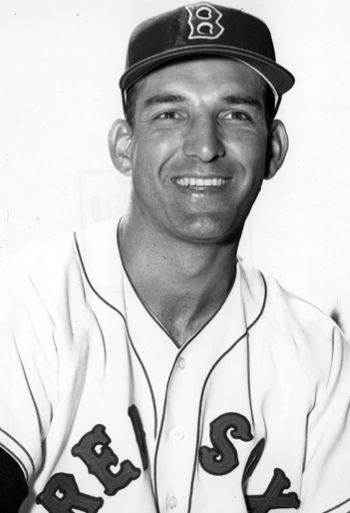

Harry Agganis

More than five decades later, his legend has not faded. The people who saw Harry Agganis play or knew him still talk both of the joy he gave to New England and of the devastating grief brought by his tragic end. Their children might know of him by walking on Harry Agganis Way, by attending an event at Agganis Arena with its lifesize statue of the hero out front, or watching the Harry Agganis Football Classic in his hometown of Lynn, Massachusetts. Though his professional career was brief, he built his fame in high school and college, leaving him, arguably, the greatest athlete ever to emerge from the Greater Boston area. To top it off, he appears to have been loved by everyone who ever knew him. George Sullivan, his college teammate and later a historian of the Red Sox, wrote, “Worry not about the Agganis legend. This is one hero whose statue does not have feet of clay. Harry was the real thing, an ideal off the playing fields as well as on them.”

More than five decades later, his legend has not faded. The people who saw Harry Agganis play or knew him still talk both of the joy he gave to New England and of the devastating grief brought by his tragic end. Their children might know of him by walking on Harry Agganis Way, by attending an event at Agganis Arena with its lifesize statue of the hero out front, or watching the Harry Agganis Football Classic in his hometown of Lynn, Massachusetts. Though his professional career was brief, he built his fame in high school and college, leaving him, arguably, the greatest athlete ever to emerge from the Greater Boston area. To top it off, he appears to have been loved by everyone who ever knew him. George Sullivan, his college teammate and later a historian of the Red Sox, wrote, “Worry not about the Agganis legend. This is one hero whose statue does not have feet of clay. Harry was the real thing, an ideal off the playing fields as well as on them.”

Aristotle George (Harry) Agganis was born on April 20, 1929, in Lynn to George Agganis and the former Georgia Papalimberis. The couple met in Lynn after each had emigrated from Greece, and married in October 1906. Aristotle (Harry was a derivation of his family nickname, Ari)1 was the last of their seven children. The family lived on Waterhill Street in West Lynn, in a largely Greek neighborhood. Harry spoke mainly Greek at home, and attended a Greek Orthodox Church.2

Harry quickly became renowned as a great athlete in his neighborhood and city. Having already earned the nickname the Golden Greek, Agganis was a three-sport star at Lynn Classical High School, about 10 miles north of Boston. As a teenager, he played baseball at Lynn’s venerable Fraser Field and in 1946 he traveled to Chicago for the Esquire All-American Boy game at Wrigley Field. By then, the Red Sox had established a Class B New England League farm team in Lynn. Dick O’Connell, who eventually became general manager of the Red Sox, served as Lynn’s business manager. O’Connell had been able to watch Agganis closely, and reportedly persuaded the Red Sox to hire Harry’s high-school football and baseball coach, Bill Joyce, as president of the Lynn Red Sox. Harry worked out with the team on occasion, in addition to working odd jobs for the club.3

In 1947, Harry hit .352 to lead Lynn Classical to the Massachusetts state baseball championship.4 He was named the state’s player of the year, and was chosen to play in the Hearst All-Star game at the Polo Grounds in New York. After graduating from high school, Agganis spent the summer of 1948 playing for the Augusta Millionaires in Maine, where he starred with future Red Sox teammate Ted Lepcio.5

As good as he was on the high-school diamond and basketball court (where he was a star ball-handling center), Agganis earned even more fame on the gridiron, attracting crowds of more than 20,000 to Lynn’s Manning Bowl.6 As a left-handed quarterback, defensive back, kicker, and punter, he led his team to a 21-1-1 record over two seasons. Following an undefeated junior year in 1946, he and his teammates traveled to Miami, Florida, where they defeated Granby High of Norfolk, Virginia (whose roster included future Red Sox pitcher Chuck Stobbs), in the Orange Bowl on Christmas Day to win the mythical national high-school football championship.7 “That young man could step into any college backfield right now,” raved Tennessee football coach General Bob Neyland.8 Agganis and his teammates declined an invitation to a similar game following his senior year when they were told they could not bring their two African-American players.9 Over his three-year high-school football career, the All-American Agganis completed 65 percent of his passes (326 for 502) for 4,149 yards and 48 touchdowns. He also rushed for 24 more touchdowns, kicked 39 extra points, and averaged more than 40 yards per punt.10

Agganis received scholarship offers from no fewer than 75 colleges, including such programs of national renown as Notre Dame and the University of Tennessee. Fighting Irish head coach Frank Leahy had dubbed Harry “the finest prospect I’ve ever seen.” 11 Agganis, whose father, George, had died in 1946, surprised many football observers when he decided to attend Boston University to remain close to his widowed mother.

Red Sox fans did not have to travel far to catch Agganis in action on the gridiron, as the BU Terriers played their home games at Fenway Park. As he had in high school, Harry wore jersey No. 33 to honor his hero, standout Washington Redskins quarterback Sammy Baugh. Playing for the freshman squad, Agganis was 29-for-52 for 492 passing yards and five touchdowns in four games. He averaged 4.7 yards per carry rushing and scored four touchdowns on the ground.12

As a sophomore in 1949, Agganis set a school record with 15 touchdown passes while completing 55 of 108 tosses for 762 yards. He also rushed for 5.4 yards per carry, scored two touchdowns on the ground13, intercepted 15 passes on defense14, and led the nation in punting with a 46.5 yard average.15 Harry was named a second-team All-American, finishing behind future NFL and AFL star quarterback Babe Parilli of the University of Kentucky.16

Agganis’s college career was next interrupted by the Korean War. He had enlisted in the United States Marines’ 2nd Infantry Organized Reserve Battalion while in high school, and was called to active duty in the spring of 1950. Though he never went overseas, Harry served a 15-month hitch at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, where he played for the football and baseball teams. In the summer of 1950, Agganis hit .362 to lead his team to a 72-17 record against clubs stocked with former major-league pitchers.17 His squad reached the National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita, Kansas, and Harry was named Most Valuable Player.18

Agganis later requested a dependency discharge to help support his mother, and returned to school in September 1951.19 He arrived home just two days before the Terriers’ football opener at William & Mary and got in an hour of practice before throwing a pair of touchdown passes.20 As a junior that fall, Harry threw for 14 touchdowns and a school record 1,402 yards, completing 104 of 185 passes, and earned the Bulger Lowe Award as the best collegiate football player in New England.21 In the spring of 1952, Agganis hit .322 for the Terriers in his return to the baseball diamond.22 Twice appearing on the cover of the prestigious Sport magazine, in the spring of 1952, Agganis was selected with the 12th overall pick in the first round of the National Football League draft by Paul Brown, coach of the Cleveland Browns, who wanted Agganis to succeed legendary quarterback Otto Graham.23 Instead, Agganis chose to return to Boston University for his senior season.

Nowhere was Agganis’s fame greater than in his hometown of Lynn. When members of Lynn’s Greek community held a benefit dinner in Harry’s honor, he refused to keep any of the money raised. Instead, he sent it to the small village in Greece near Sparta, from which his parents had emigrated, to purchase sports equipment for its children. No one who knew Harry Agganis was surprised.24

The football team struggled in 1952. Attracted by the promise of large gate receipts from the huge crowds flocking to watch Agganis, larger schools with far more powerful teams pined for slots on the Terriers’ schedule. Many of Harry’s teammates were still fulfilling their military commitments as the Korean War dragged on, leaving BU with a largely inexperienced and undersized lineup. For the most part, Harry was up to the challenge and was able to keep his team competitive against larger and faster opponents. On October 10, the University of Miami came to Fenway Park as a three-touchdown favorite, but Agganis intercepted two passes, made 14 tackles and punted for 58, 65, and 67 yards. His final kick resulted in a safety for the decisive points in a 9-7 upset win.25

Three weeks later, on November 1, a crowd of 32,568 fans packed Fenway to watch the Terriers take on the University of Maryland, which had entered the season as the second-ranked team in the nation.26 The game was broadcast nationally by Vin Scully, who called the action from Fenway’s rooftop in his first-ever assignment with the CBS Radio Network.27 Maryland had played BU in 1949, and the Terriers had given the Terps more than they could handle before losing a 14-13 squeaker. In the rematch, according to contemporary accounts, the Terrapins focused on beating BU’s overmatched offensive line and getting physical with Agganis. Several gang tackles by Maryland defenders bruised his ribs so badly that he had to be helped off the field in a 34-7 loss. Though X-rays were negative, Harry continued to have difficulty breathing and missed the next two games.28

Despite the missed time, Agganis completed 67 of 125 tosses for 766 yards and five touchdowns in seven games that year. He finished his Terriers football career with 15 school records. Although most have been surpassed by athletes who played four years, Harry set his marks in just three varsity seasons — racking up 2,930 passing yards, and 34 touchdowns while completing 226 of 418 passes, or 54 percent. 29 His records extended to defense and special teams, as he amassed 27 career interceptions and a 39.5-yard punting average.30

After his final football game, on November 28, 1952, Harry signed with the hometown Red Sox for $50,000 — far less than the reported $100,000 bonus offered by the Cleveland Browns. A report quoted Agganis:

“I’ve been torn between baseball and football for a long time, but have finally made up my mind to concentrate on baseball. I’ve already proved myself in football. I don’t know if I can make it in baseball, but I have the confidence that I can. I expect to be farmed out to a minor league club for a year, regardless of how I do in the South [spring training]. I’ve always wanted to be a baseball player, but I never wanted to say it until my football days were over.”31

If Agganis’s decision seemed rushed, there was a good reason: His signing came one week before the major leagues’ “Bonus Baby” rule went into effect, which required any players signed with a bonus larger than $4,000 to remain with the major-league club for two full seasons. Because he beat the deadline, Harry was able to get a higher bonus and still benefit from some minor-league seasoning.

The Red Sox granted Agganis special permission to play one final college game — the all-star Senior Bowl in Mobile, Alabama, in January 1953. Harry played all but one minute of the game and earned Most Valuable Player honors, throwing two touchdowns, rushing for another, and hauling in a pair of interceptions as the North beat the South, 28-13.32 After that game, football legend Red Grange proclaimed Agganis the best player he had seen all year.33

In 1953 Agganis, a left-handed-hitting and throwing first baseman, went to Sarasota to train with the Red Sox, but was soon optioned to Louisville. He had a fine year in the American Association, with 23 home runs and 108 RBIs, finishing second (to Don Zimmer of St. Paul) in the voting for league Rookie of the Year award. In 1954 he came to camp to battle Dick Gernert for the first-base job.34 Conventional wisdom held that this would be a tall task for a left-handed hitter at Fenway due to the 380-foot distance from home plate to the right-field bullpen fence. Gernert, a righty who evoked images of Jimmie Foxx, had clubbed 21 homers in 1953. Yet as spring training wore on, Roger Birtwell of the Boston Globe reported35 that Agganis seemed to be winning the battle:

“Judging from the form the two players have shown in Spring training, however, it would not be surprising if Agganis eventually eases Gernert out of the picture. For Agganis, a promotion seems richly deserved. He has outhit Gernert down here by a hundred points. Agganis has consistently outplayed Gernert in the field.”

Meanwhile, Paul Brown was still trying to recruit Agganis for his Cleveland Browns. Billy Consolo, who roomed with Harry that spring, recalled Brown phoning every day in an attempt to persuade him to give up baseball, but without success.

Agganis would indeed open 1954 in the starting lineup, making his presence felt immediately. Wearing jersey number 6, he made his big-league debut against the Philadelphia Athletics on April 13, 1954, pinch-hitting in the eighth inning. On April 15 at Fenway Park, Agganis started at first base and went 2-for-3, crushing a deep drive to right field off Washington’s Bob Porterfield for an RBI triple. 36 Observers noted that he would have had an inside-the-park home run if not for having the sloth-like George Kell on base ahead of him.37 Three days later, in the nightcap of an April 18 doubleheader, Harry hit his first major-league home run, a three-run shot, at Fenway off the A’s Arnie Portocarrero to carry the Red Sox to a 4-3 win. A day after that, Agganis singled for the lone hit off Yankees pitcher Jim McDonald in the second game of the Patriots Day twin bill at Fenway Park.38

“I hope he can make the grade,” said Red Sox general manager Joe Cronin. “He’s colorful. He’s a good competitor. And being a local boy, he can be a great drawing card.” This was no trivial matter — the Red Sox’ attendance had peaked in 1949 at nearly 1.6 million, but 1954 would mark their fifth consecutive decline, down to 930,000. The club organized a campaign to “Fill Fenway” for the home opener, getting support from the mayor’s office, but drew only 17,000 fans. Agganis had seen bigger crowds in high school and college than he saw in the major leagues.

Other highlights of his first season with the Sox included a four-RBI game with a homer and a double against the A’s on May 31, and a grand slam at Yankee Stadium on August 15.39 His best day was on June 6: He homered to help the Red Sox beat the Tigers 7-4, and then headed to Boston University for commencement exercises, where he was awarded his bachelor’s degree in education.40 Gernert, originally slated to platoon at first with Agganis, contracted hepatitis shortly after the season began and played just 14 games. Agganis hit .251 with 11 homers (including seven at Fenway), 54 runs, and 57 RBIs, in 132 games.41

After the 1954 season, Mike Higgins, Harry’s manager at Louisville, replaced Lou Boudreau at the Red Sox helm. The biggest position battle the next spring involved Agganis, who was now challenged at first base by rookie Norm Zauchin. A big right-handed hitter, Zauchin had fared well for Higgins in Louisville in 1954, while Agganis had slumped in the second half of his rookie campaign. Zauchin outhit Agganis in spring training and earned the position to start the season. After Zauchin went hitless in the season’s first three games, Agganis started the next three. By May 4, Zauchin was hitting .189 and Agganis got the job. With Ted Williams temporarily “retired” (he returned in May after a divorce settlement), Agganis began hitting in Ted’s customary third slot in the batting order. Over the next month, Agganis hiked his batting average above .300. On May 15, in a home doubleheader against the Detroit Tigers, Agganis went 5-for-10 with two doubles and a triple, boosting his average to .307, tenth in the league.42 For the many local observers accustomed to Agganis’s extraordinary athletic achievements, he was on his expected path to greatness.

After the twin bill, the Red Sox were in fifth place, 7½ games out of first with a record of 14-18. Players were looking forward to their offday, but Agganis arrived at Fenway seeking trainer Jack Fadden. Harry was experiencing heavy coughing spells and severe pain in his right side. After Fadden detected a fever, Agganis was admitted to Sancta Maria Hospital in nearby Cambridge. The team physician, Dr. Timothy Lamphier, diagnosed pneumonia in the right lung, and Harry remained hospitalized for 10 days.43

Agganis rejoined the team on May 27 for a series with the Washington Senators, but did not play. He appeared weak and pale, his cough persisted, and he was perspiring heavily. Harry sat that day as Zauchin notched three home runs and 10 RBIs in a 16-0 rout, apparently reclaiming the starting job at first. Agganis finally got a start five games later in Chicago. The next day, June 2, against Virgil Trucks and the White Sox, Harry again made the start at first. With Williams back in the lineup, Agganis batted fourth behind his star teammate. Harry went 2-for-4, including a shot to the gap for a double. It appeared to be deep enough for a triple, but after reaching second base Agganis stopped and sat down atop the base, exhausted. Later, with two on and two out and the Sox behind 4-2, Harry hit a short fly to right fielder Jim Rivera, who made a circus catch, then doubled off Williams as first base to end the inning.44 It proved to be the final plate appearance of Harry Agganis’s life. He had hit .313 for his season with 10 doubles, a triple, and no home runs.

The team boarded a train to Kansas City that evening while Harry’s cough persisted. After trainer Fadden examined him the next morning, Agganis was put on a plane back to Boston, where Joe Cronin picked him up and drove him back to Sancta Maria Hospital. A trio of new physicians diagnosed Harry with pneumonia in his left lung and phlebitis in his right leg. Agganis told the doctors that he had noticed a lump on his calf in April, which turned out to be a swollen venal wall. The medical staff kept his leg wrapped in ice to fend off blood clotting, and Harry remained weakened by his coughing spells. The doctors then announced that Agganis would be sidelined for two months, with Dr. Eugene O’Neill stating:

“Harry was a lot sicker than he realized when he entered the hospital. His case is a very complicated and serious one. If his condition warrants, he could be idle all season.”45

Harry’s condition did not improve, and the team placed him on the voluntary retired list on June 16.46 On June 25, after a visit from Ted Williams (who brought him a Davy Crockett magazine), Harry’s brother discovered him coughing up blood. On the morning of Monday, June 27, the physicians had him sit upright in a chair for the first time. As the doctors and nurses lifted Agganis from his bed, he clutched his chest and complained of pain. A blood clot had broken free from the vein in his calf and reached his lung, causing a pulmonary embolism. Twenty minutes later, the great Harry Agganis, idol of a region, was dead at the age of 26.47

He was survived by his mother, four brothers and two sisters.48 Before he died, Agganis allegedly whispered to a nurse, “Take care of my mother … be sure she is alright.”49

News of Agganis’s death cast a pall over Boston and Lynn and the surrounding region, and people who lived through the period can still tell you where they were when they first heard the news. “Everyone connected with the Red Sox is grieved and shocked,” a stunned Cronin said. “Harry was a great athlete, a grand boy, and a credit to sports.”50 Manager Mike Higgins was equally stunned: “He had it made. We thought he’d be our first baseman for ten years to come.”51

Harry’s Red Sox teammates, who had just finished a successful 11-3 homestand, were in Pittsburgh for an exhibition game when they got the word from traveling secretary Tom Dowd. The Red Sox played the game, losing 8-2, and then traveled by train to Washington for a series with the Senators.52 Seemingly inspired, they swept a doubleheader on the 28th, 4-0 and 8-2, and won again the next day, 7-5.53

His body lay in a bier at St. George Greek Orthodox Church in Lynn for a day and a half. More than 10,000 mourners filed past the coffin at his wake the evening of June 29.54 Harry was dressed in his favorite blue suit, a wreath of apple blossoms atop his head, and a gold wedding band placed around his left ring finger in accordance with Greek custom, symbolic of his eternal marriage to God.55 Hundreds of uniformed Little Leaguers stood outside the church, where the wake was held to accommodate the throng.56

The funeral was held the next day at 2 P.M. The Red Sox sent pitcher Frank Sullivan to represent the players, since the team was scheduled to play the final game of the Senators series in Washington that same afternoon, with a portion of gate receipts to benefit the American Red Cross. Cronin had hoped the entire team would be able to attend Harry’s service, but he was unable to persuade Senators owner Calvin Griffith to cancel or postpone the game. Because of the charitable connection, Cronin relented, though he was able to get the start time moved back an hour, to 3 P.M.57

Turnout for the Thursday game in Washington was sparse, and some accounts claimed that actual attendance was far less than the official figure of 8,563.58 A pair of Greek Orthodox priests conducted a service at home plate before the game, as the teams and umpires stood along the baselines at Griffith Stadium with heads bowed. A Marine color guard dipped the American flag in a traditional show of respect for the deceased serviceman.59

Sammy White delivered a stirring eulogy of his teammate and friend:

“The task that confronts me today is indeed a most difficult one, difficult because it is quite impossible to find the right words to completely express the deep sorrow we all feel for the loss of our teammate. How to tell his mother, his sisters and his brothers just how deep is our sympathy for them presents another difficulty. To tell all you people what Harry Agganis meant to me and his teammates really has me groping for appropriate words. Harry was not only a talented athlete with the strength of a Hercules, the competitive spirit and courage of a lion, and the possessor of an almost ferocious desire to win — he was a leader and, at the same time, a follower of all that was good.”60

Red Sox radio announcer Curt Gowdy then took the microphone to address those in attendance and said, with a shaky voice, “His athletic feats were golden and shining, and so was Harry personally.” Gowdy teared up again during the radio broadcast of the game. Ted Williams, the only player who had been allowed to visit Harry in the hospital,61 was unable to contain his emotions and wept on the field.62 The Red Sox wore black armbands for the next 30 days.63

Meanwhile in Lynn, 1,000 people packed into the church while thousands more filled an adjacent hall or stood outside in stifling summer heat. Many cried as they listened to the services on loudspeakers and transistor radios — first in Greek, then in English. Frank Sullivan later said it was one of the saddest things he had ever seen. Joining him from the Red Sox organization were Higgins, Cronin, O’Connell, scout Neil Mahoney, secretary Mary Trank, and several others from the front office. Sox owner Tom Yawkey was so uncomfortable with funerals that he remained at his plantation in South Carolina. He later made a $25,000 contribution to the Agganis Foundation.64

Twenty thousand people lined the one-mile funeral route from the church to Harry’s hillside grave in Pine Grove Cemetery, overlooking the Manning Bowl, where many of his sports heroics had played out. Nine vehicles carried the hundreds of floral arrangements sent by teammates, classmates, and opponents past and present, friends, family, fellow soldiers, and total strangers. 65

Questions persist about how such a strong, vibrant athlete could die surrounded by numerous doctors and nurses. The tiny Cambridge hospital where Harry was being treated and died was the Red Sox’ team hospital, and was thought by many to have lacked the staff or technology of Boston’s large and famous hospitals such as Massachusetts General. Many people, including Red Sox assistant GM Dick O’Connell, believed Harry’s illness stemmed from the injuries he received in the 1949 football game with Maryland. “I always felt the beating he took that day contributed to his death. I’m no doctor but I suspect blood clots sometimes don’t show up for a while,” said O’Connell later.66

Harry’s friend Dick Lynch long claimed that Dr. Lamphier had proposed surgery to strip the blood veins in his legs to mitigate any clot hazards, but that the procedure would have limited his agility, a prospect Harry flatly refused to consider, according to Lynch.67 Jack Kelley, another classmate of Harry’s, backed up these assertions: “I heard they told him they wanted to tie off some leg veins because clots were a possibility. But they told him he’d have no speed after that so he wanted to see if he could get better without that treatment. He thought he was getting better and would take his chances.”68

That scenario certainly adds to the mystery surrounding the removal of Dr. Lamphier from Harry’s case. Having seen the swelling in Harry’s calf, he allegedly tried to warn the team of the dangers a blood clot might pose but was met with ignorance and ultimately replaced as Harry’s attending physician. While one might see plausibility in that claim, Lamphier’s personal and professional credibility took a hit when he later moved to Florida and lost his medical license following the deaths of several patients.69

According to some Agganis researchers, including a present-day spokesman for the family, prior to his death Harry had already decided to return to football. If true, he would have played quarterback that fall for the Baltimore Colts, who had acquired his rights from the Browns.70

Harry Agganis’s legend remains strong and visible in the Boston area. His football number 33 was retired at both Lynn Classical and Boston University soon after he graduated from each school. In 1953, Harry was inducted into the new Boston University Hall of Fame.71 He declined gifts of a car and $4,000 from his classmates and instead asked that the cash equivalent be put toward establishing a Boston University scholarship for Greek-American students with financial need.72 In May 1955, Cleo Sophios of Medford High School was the first recipient. Agganis was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1974.73

In 1995, Gaffney Street in Boston was renamed Harry Agganis Way in his honor.74 It is located near Nickerson Field, which sits atop the former site of Braves Field, and was home to the Boston University football team. (The university has since dropped football.) In 2004, Agganis Arena, a 7,200-seat sports and entertainment facility, was dedicated in Harry’s honor on the Boston University campus.75 The arena is home to the Terriers’ ice hockey and basketball teams. A life-size bronze statue of Agganis, sculpted by artist Armand LaMontagne and depicting Harry about to throw a football, stands outside the arena’s main entrance.76 A wooden statue by LaMontagne, depicting Agganis in a pose similar to his work in bronze, can be seen at the New England Sports Museum at Boston’s T.D. Bank Garden.77

The Agganis Foundation was established in 1956 by the Boston Red Sox, the (Lynn) Daily Item newspaper and Harold O. Zimman, who was a mentor of Harry. Elmo Benedetto, the athletic director for the Lynn public schools, also joined the board of directors. It was a continuation of the scholarship foundation Harry himself started just prior to his death. From its inception through 2007, the Agganis Foundation has awarded $1,187,525 in scholarships to 780 student-athletes from throughout Eastern Massachusetts. Each year, 15 new four-year, $4,000 scholarships are presented. Through the additional generosity of the Yawkey Foundation, there are four scholarships earmarked to students in Boston schools each year. The foundation also sponsors the Agganis All-Star Classics, a series of high-school all-star games. The football classic, first organized by Benedetto, has been played annually since 1956 with the exception of 1960-64, and the 50th Anniversary Classic was to be played in the summer of 2010. Other Classics have since been added for baseball (1995), men’s and women’s soccer (1996), softball (1997), and men’s and women’s basketball (2005).78

Agganis’s legend goes far beyond his feats on the playing fields. He was revered as a person at every stage of his life. In high school he not only dominated athletically, he also starred in school plays, performing with his girlfriend Jean Allaire, who went on to play Miss Jean in Romper Room, a local children’s television show. “The thing about Harry,” recalled Dick Lynch, a friend and teammate in both high school and college, “was that he was such a classy guy. He handled everything about his fame so beautifully. He was an idol — the Greek god image was an understatement — but he never let any of it go to his head.” Mary Trank, who worked in the Red Sox offices at the time, was one of the awestruck: “When he walked into a room it was like an aura,” she said.79

“Almost everybody on the North Shore knew him all right,” wrote Jeremiah Murphy in the Boston Globe. “I’ll tell you right off: I never heard anybody put the knock on Harry Agganis. There was no question about that. Harry was as charismatic off the field as he was when he was throwing beautiful 60-yard touchdown passes in Manning Bowl. You couldn’t take your eyes off him if he walked into a room. It was a real privilege to have seen him play and to have been in his presence.”80 George Smyrnios, who played against Agganis at Peabody High felt privileged for the chance: “We became immortalized with him. He was a champion above champions, a super player. He was the best of the best and an unbeatable player and an unbeatable person.”81 Bob Whalen, another college teammate, said, “He had that unique knack of making you feel you were the most important person in the world to him. He’d walk into a room and the room would just light up.”82

Decades later, there were still people in the Boston area who would talk about the time they saw, or met, Harry Agganis, how much he meant to them, how much his loss was still felt. What he would have accomplished in his baseball career is not known. Nonetheless, in his 26 years he managed to affect the lives of tens of thousands, who will never forget him.

Sources

Much of this biography was reworked from Mark Brown’s story on Agganis found at the Sons of Sam Horn wiki page. (http://sonsofsamhorn.net/wiki/index.php/Harry_Agganis).

Notes

1 Jean Hennelly Keith, “Harry Agganis – The Golden Greek,” Advancement (a publication of the Boston University Alumni office), Summer 2002.

2 Nick Tsiotis and Andy Dabilis. Harry Agganis, The Golden Greek: An All-American Story (Hellenic College Press, 1995).

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

6 George Sullivan, “Biography,” http://www.agganisfoundation.com/bio/bio.html.

7 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

8 Sullivan.

9 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

10 Sullivan.

11 Christopher L. Gasper, “Agganis Legend Lives,” Boston Globe, June 26, 2005.

12 Boston University Hall of Fame Web Site, www.goterriers.com/hallfame/agganis-harry.html.

13 Ibid.

14 Tsiotis and Dabilis, op. cit.

15 Boston University Hall of Fame website.

16 Tsiotis and Dabilis, op. cit.

17 Brian Berger, “Legend of Golden Greek lives on 50 years later,” MCB Camp Lejeune Press (Camp Lejeune, North Carolina), April 4, 2005.

18 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

19 Berger.

20 Sullivan.

21 Boston University Hall of Fame website.

22 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

23 Sullivan.

24 Hugh Wyatt, “Harry Agganis – The Golden Greek,” www.coachwyatt.com/harryagganis.htm

25 Sullivan.

26 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

27 Jack Craig, “Scully completes cycle at Fenway,” Boston Globe, July 9, 1989.

28 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

29 Boston University Hall of Fame website.

30 National Football foundation, College Football Hall of Fame web site, www.collegefootball.org/famersearch.php?id=50006

31 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

32 “Senior Bowl Star Gives Up Football For Diamond Sport,” The Free-Lance Star (Fredericksburg, Virginia), January 5, 1953: 5.

33 Boston University Hall of Fame website.

34 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

35 Ibid.

36 Harry Agganis player page and game logs at www.baseball-reference.com.

37 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

39 Ibid.

40 Wyatt.

41 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

43 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

44 Ibid.

45 Ibid.

46 “Harry Agganis of Boston Red Sox Dies,” New York Times, June 28, 1955.

47 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

48 “Harry Agganis of Boston Red Sox Dies”.

49 Berger, op. cit.

50 Mark Armour, Joe Cronin: A Life in Baseball. University of Nebraska Press, 2010.

51 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

52 Ibid.

54 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

55 “Agganis Now Wed To God In Tradition Of Greeks,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 30, 1955, 20.

56 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

57 Ibid.

59 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

60 Ibid.

61 Ibid.

62 Ted Williams, My Turn At Bat, Fireside/Simon & Schuster, 1984, 15.

63 The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. “Dressed To The Nines: A History of the Baseball Uniform – Parts of the Uniform,” exhibits.baseballhalloffame.org/dressed_to_the_nines/patches.htm.

64 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

65 Ibid.

66 Sullivan.

67 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

68 Ibid.

69 Ibid.

70 Gasper.

71 Boston University Hall of Fame website.

72 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

73 “BU Yesterday,” B.U. Bridge, week of October 29, 2004 (Vol. VIII, No. 9), www.bu.edu/bridge/archive/2004/10-29/bu-yesterday.html.

74 “Lynn Sports History,” City of Lynn (Massachusetts) web site, www.ci.lynn.ma.us/aboutlynn_sports_history.shtml.

75 “Harry Agganis, The Golden Greek,” Agganis Arena web site, www.agganisarena.com/about/arena/harry.html.

76 “The Golden Greek in bronze,” B.U. Bridge, May 13, 2004 (Vol. VII, No. 30), www.bu.edu/bridge/archive/2004/05-13/agganis.html.

77 Saul Wisnia, “Shaping The Splendid Splinter, And Others,” Sports Illustrated, January 22, 1996, sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1007660/index.htm.

78 “About Us,” Agganis Foundation website, www.agganisfoundation.com/about/about.html

79 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

80 Jeremiah V. Murphy, “Harry … Only One Name Was Needed,” Boston Globe, June 27, 1980.

81 Tsiotis and Dabilis.

82 Ibid.

Full Name

Harry Agganis

Born

April 20, 1929 at Lynn, MA (USA)

Died

June 27, 1955 at Cambridge, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.