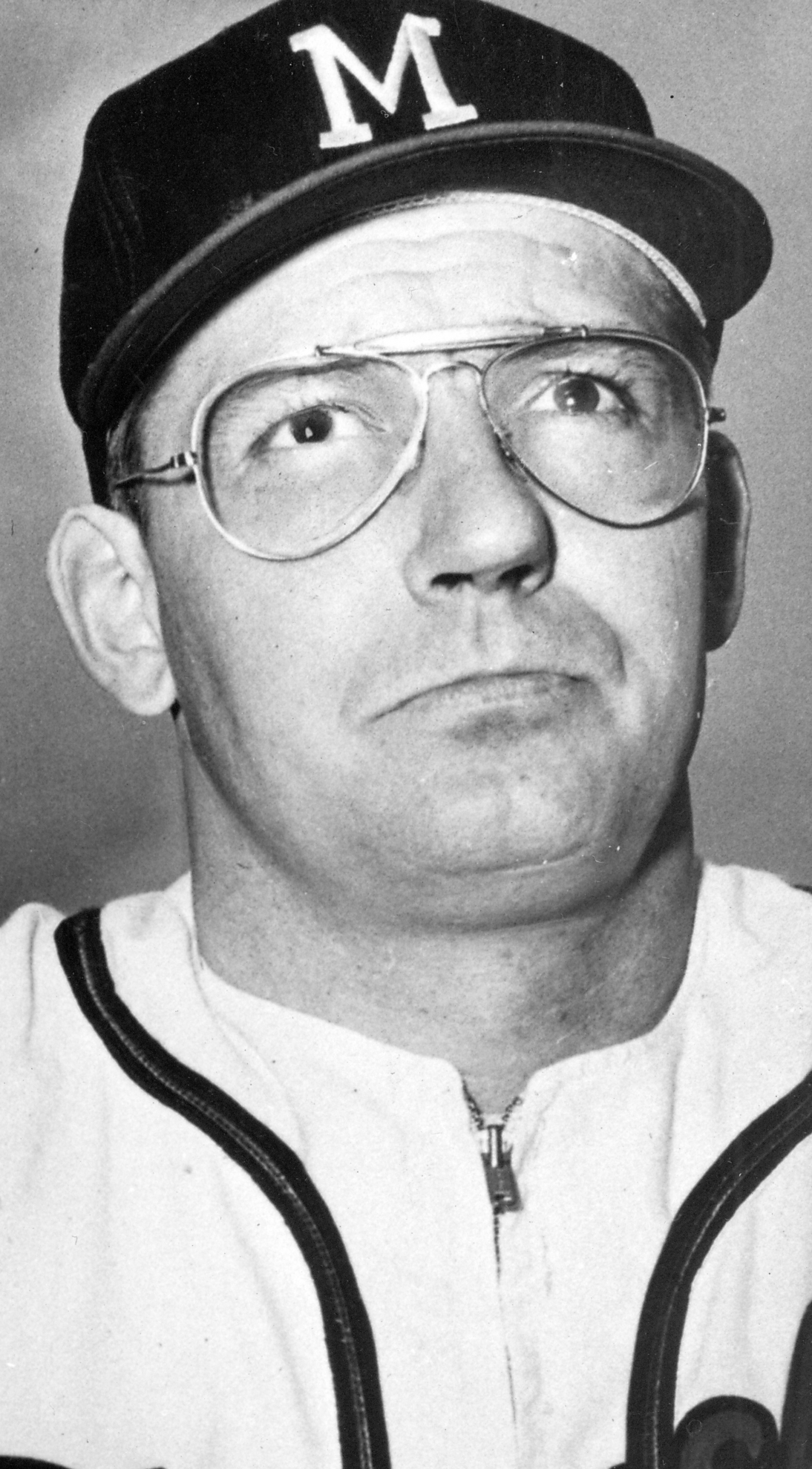

Harry Hanebrink

A versatile defender who played as a utilityman in both the infield and outfield, Harry Hanebrink played for the two Milwaukee Braves teams that won the National League pennant in the 1950s, one of which won the World Series. He was also part of a much larger team that captured an even more important victory – the Allied Forces in World War II, during which he served in the US Navy.

A versatile defender who played as a utilityman in both the infield and outfield, Harry Hanebrink played for the two Milwaukee Braves teams that won the National League pennant in the 1950s, one of which won the World Series. He was also part of a much larger team that captured an even more important victory – the Allied Forces in World War II, during which he served in the US Navy.

Harry Aloysius Hanebrink was born on November 12, 1927, in St. Louis to Harry C. and Christina Hanebrink. He was the Hanebrinks’ second child, joining older sister Christine. Their father worked for a newspaper in the St. Louis area.[1]

Harry attended McBride High School, a Catholic school about six miles northwest of downtown St. Louis. (The school closed its doors in 1975.) He joined the Navy on June 21, 1945, shortly after graduating, and served until he was discharged in August of 1946.

Hanebrink signed with the Boston Braves organization and began his professional baseball career with the Eau Claire Bears of the Class C Northern League in 1948. There is some dispute about exactly how Hanebrink came to join the Braves organization; two contemporary accounts offer competing versions. A Braves team publication listed Hanebrink as having signed with scout Bill Maughn, while The Sporting News said that Hanebrink signed with the club via Rich Keely, a scout whose brother Bob was a bullpen catcher for the team.[2]

Regardless of the scout who brought Hanebrink into the fold, Hanebrink put up impressive numbers at Eau Claire, leading the team in hits, triples (13), and home runs. His 16 round-trippers tied for the league lead. Hanebrink finished fourth in the league in batting average (.290), trailing among others teammate Chuck Tanner, the only other member of the squad to go on to a major-league career. The left-handed-hitting Hanebrink’s power display was an anomaly, likely due in part to the 312-foot right-field fence at Eau Claire’s Carson Park. The triple and home-run totals are surprising given Hanebrink’s major-league height and weight, which were listed at 6-feet and 165 pounds. After his 16 homers as a 20-year old in 1948, he didn’t hit more than eight home runs in a season again until 1956, eight years after his initial outburst.

In 1949 and 1950 Hanebrink put up similar numbers to 1948 as he rose in the minor-league ranks, playing with Evansville of the Class B Three-I League in 1949 and Hartford of the Class A Eastern League in 1950.

In 1951 Hanebrink returned to Hartford and increased his batting average 19 points to .309 (sixth in the league), earning all-star honors. The offensive output was enough to elevate Hanebrink’s standing with the Braves, who had always held his fielding prowess in high esteem. Before the 1952 season the Braves initiated a “Rookie Rocket” tour, in which team executives and media members flew around the country to become familiar with minor-league players the team felt would contribute to the major-league club in the near future. After his strong performance in successive seasons, Hanebrink’s St. Louis home made its way onto the list of tour stops.

For 1952 the Braves promoted Hanebrink to the Atlanta Crackers of the Double-A Southern Association. Hanebrink posted a solid season, hitting .291 with six home runs and playing in a team-high 145 games.

Along the way in the minors, Hanebrink made an impression not just because of his play but also because of his unique style at the plate. Of his stance, which he adopted to help him combat overstriding at changeups, he said, “Feet very wide. I don’t even take a step, but I come forward with the bat three times then take one fast cut when the pitcher starts to throw. All the fans used to count cadence on every pitch at Hartford, clapping and shouting: ‘One, two, three, dip.’ I guess it looks funny, but I can hit better that way.”[3] His Atlanta teammates nicknamed him “The Stance” because of his unique approach. At one point Hanebrink was in a slump at the plate and Atlanta manager Dixie Walker told him that no one would be able to help him because of his unorthodox style. Hanebrink abandoned the stance for a time but continued to struggle, so he eventually returned to his old reliable way and started hitting again.[4]

After five seasons in the minor leagues, Hanebrink reached the majors in 1953, the Braves’ first season in Milwaukee after the franchise moved from Boston, leading baseball’s westward migration. He made his big-league debut at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn on May 3, pinch-hitting and grounding out for Braves pitcher Max Surkont in the fifth inning against Brooklyn’s Billy Loes. After batting seven times without success (and never more than once in a game), Hanebrink got his first big-league hit on June 6, a two-run pinch-hit home run at Connie Mack Stadium off the Phillies’ future Hall of Famer Robin Roberts. Hanebrink did not hit another major-league home run for nearly five years.

Despite spending almost the entire 1953 season with Milwaukee, Hanebrink did not get his first start in the big leagues until August 7, when he played second base and batted eighth in the Braves’ 9-2 win over Pittsburgh. That start came the day after he hit a game-winning bases-loaded triple off Russ Meyer of Brooklyn. After the game-winner, Hanebrink started the next 11 games, but after August 16 he started only three more the rest of the season. For his inaugural major-league season Hanebrink hit .238 with one home run and eight RBIs. He appeared in 51 games overall, but came to bat only 87 times, as many of his appearances were as a pinch-hitter or defensive replacement.

After the 1953 season, Hanebrink did not appear in a major-league game again until late 1957. He spent 1954 and 1955 with Toledo, the Braves’ Triple-A team in the American Association, and after the franchise was moved to Wichita, he spent all of 1956 and most of 1957 there. During this four-year stretch he hit .272 and saw action primarily at third base, although he played every position except pitcher and catcher for Toledo in 1955. Hanebrink’s power jumped substantially at Wichita in 1956 and 1957 (20 and 24 home runs, no doubt due in part to the left-handed hitter taking advantage of another 312-foot right-field fence at Wichita’s Lawrence-Dumont Stadium).

Hanebrink was called up to the Braves early in September of 1957, going 2-for-7 in six games as the Braves captured the NL pennant by eight games over the Cardinals and then bested the Yankees in seven games in the World Series. As a call-up after the September 1 deadline, Hanebrink did not play in the Series. Hanebrink spent all of 1958 with the Braves. It was the only one of his 14 professional seasons in which he spent no time in the minor leagues. Not surprisingly, he registered major-league career highs in virtually every counting stat, including games played, at-bats, hits, home runs, RBIs, home runs, walks, total bases, and runs scored. But the numbers are deceptive: Hanebrink struggled at the plate all season, finishing with a batting average of only .188. One highlight for him came on June 15 when his two-run home run in the ninth inning gave the Braves a 4-2 win over the St. Louis Cardinals. With the game taking place in his hometown of St. Louis, it was extra sweet for Harry, whose parents were at the game.

“I’ve been strangling that bat all season,” Hanebrink said of his struggles. “In trying to find a comfortable grip, I’ve practically squeezed all the sawdust out of it. So when I stepped up to the plate in the ninth I figured I couldn’t do any worse and relaxed my grip on the bat. It worked fine, too.”[5] But he said he understood that his was a part-time role, and he seemed eager to help the Braves in any way he could. “I can’t afford to be choosy,” Hanebrink said. “I just want to stay up here and help out wherever I can, whether it’s in the outfield or infield.”[6] Hanebrink’s role developed exactly as he suggested, as his 40 games played in the field saw him in left field 24 times, in right field nine times, and at third base in seven games. That he didn’t play more was understandable given that those three positions were manned by sluggers Wes Covington, Hank Aaron, and Eddie Mathews, respectively.

The Braves won the pennant again in 1958, by the same eight games (this time over the Pirates) and again played a seven-game World Series against the Yankees. This time, however, Milwaukee came up on the short end in Game Seven. Hanebrink went 0-2 as a pinch-hitter in Games Three and Five.

Ten days before the start of the 1959 season, Hanebrink was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies with pitcher Gene Conley and infielder Joe Koppe for catcher/first baseman Stan Lopata and infielders Ted Kazanski and Johnny O’Brien. Aside from moving from a team that was within one win of a World Series title to a team that finished in the NL cellar, Hanebrink’s role with the Phillies remained similar to what it had been with the Braves. He subbed at second base, third base, and right field, and hit .258 in 97 at-bats. He also spent some time with the Buffalo Bisons, the Phillies Triple-A affiliate.

After 1959 Hanebrink’s playing career continued for two more seasons with Buffalo. He played the corner infield spots, and hit only .219 in 310 at-bats in 1960 and ’61. After the 1961 season, Hanebrink’s 14-year professional baseball career ended.

So who was Harry Hanebrink the player? Modern metrics suggest that he was the prototypical replacement-level player. He played in 177 major-league games in four seasons. He did not have a defined position, but could play second base, third base, and the corner outfield spots. As a fringe major-league player in the 1950s, he almost certainly would have had a longer career had he come along 10 or 15 years later when the major leagues were in the process of expanding from 16 teams (in 1959, Hanebrink’s last year in the majors) to 26 teams (1977).

After leaving baseball, Hanebrink returned to his native St. Louis and worked as a real-estate broker with Dolan Realtors for 20 years. In 1992 he began a job as a shuttle bus driver for Quik Park at Lambert-St. Louis International Airport. He remained in this role until his death on September 9, 1996, after a brain aneurysm. He was survived by his wife, Wanda (Powers) Hanebrink; his sister, Christine; two daughters; two sons; and three grandchildren. As a military veteran, Hanebrink was buried at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in St. Louis.

This biography is included in the book “Thar’s Joy in Braveland! The 1957 Milwaukee Braves” (SABR, 2014), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To download the free e-book or purchase the paperback edition, click here.

Sources

In additions to sources listed below, the author consulted Ancestry.com, the SABR Encyclopedia, and baseball-reference.com.

Notes

[1] The 1930 US Census for the St. Louis area appears to conflate two families, the Hanebrinks and the Hanebrands. Using clues derived from other sources, including later hometowns of Harry Hanebrink’s sister, Christine, and obituaries for people represented in this census information, I was able to conclude which family was actually Harry Hanebrink’s.

[2] Steve O’Leary, “Hill Turnover Tips Braves Hand on Deals,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1951, 18.

[3] “Braves Rookie Hanebrink Does Rumba at the Plate,” The Sporting News, March 12, 1952, 18.

[4] Jesse Outlar, “The Stance Goes on Big Bat Spread,” The Sporting News, May 21, 1952, 29.

[5] Red Thisted, “Hanebrink’s HR Jars Cards, 4-2,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 16, 1958, 5.

[6] “Hanebrink’s HR.”

Full Name

Harry Aloysius Hanebrink

Born

November 12, 1927 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

September 9, 1996 at Bridgeton, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.