Ina Eloise Young

Although Ina Eloise Young was not the first female baseball writer, she was quite possibly the first female sports editor at a daily newspaper.1 She was also one of the earliest beat writers, covering both semipro and minor-league baseball for seven years. Ina began writing about a wide range of local sports for her hometown paper, the Trinidad (Colorado) Chronicle-News, as early as 1905.2 Yet baseball was her passion and it quickly became her specialty. By 1907 she was reporting regularly on the area’s baseball teams; she was also serving as an official scorer for the local semipro team, the Trinidad Big Six.3 During 1908, and again in 1909, she accompanied the Big Six on their road trips, sending back reports on the games.4

Although Ina Eloise Young was not the first female baseball writer, she was quite possibly the first female sports editor at a daily newspaper.1 She was also one of the earliest beat writers, covering both semipro and minor-league baseball for seven years. Ina began writing about a wide range of local sports for her hometown paper, the Trinidad (Colorado) Chronicle-News, as early as 1905.2 Yet baseball was her passion and it quickly became her specialty. By 1907 she was reporting regularly on the area’s baseball teams; she was also serving as an official scorer for the local semipro team, the Trinidad Big Six.3 During 1908, and again in 1909, she accompanied the Big Six on their road trips, sending back reports on the games.4

She became nationally known when the Chronicle-News sent her to cover the 1908 World Series: Her reports were quoted in many newspapers, and her knowledge of baseball was praised by Tim Murnane of the Boston Globe, the dean of that era’s baseball writers.5 After marrying in 1910, she continued to cover baseball, relocating to Denver, where she reported on the minor-league Denver Grizzlies till mid-1912.6 She was also appointed to the rules committee that supervised the area’s minor-league teams.7

At a time when women couldn’t vote and were expected to marry right after high school, Ina challenged those expectations, earning the respect of her male peers and proving to doubters that a woman could be a baseball expert.

Ina Eloise Young was born on February 22, 1881, in Brownwood, Texas, about 80 miles from Abilene. (Years later, following societal customs that valued women who were young, Ina would claim she was born in 1883.8) Her parents, Robert and Louisa Young, had three children — two girls (Ina and Zoe) and a boy (Robert Jr.); Ina was the middle child. Her father worked in law enforcement and was briefly a member of the Texas Rangers.9 He also loved baseball, as did her brother. Ina seems to have inherited her father and brother’s love of the game: We don’t know much about her early years, but in 1908 she wrote a magazine article in which she recalled being a fan from the time she was a little girl.10

By 1889, the Young family had left Brownwood and moved to Trinidad, Colorado, nearly 600 miles away. Trinidad was an up-and-coming city, with a rapidly increasing population that grew from about 3,000 in the 1880s to nearly 10,000 by the 1910s, thanks to the arrival of the railroads, which made the area’s coal mines more accessible. It was also a good place to be a baseball fan: While it was too small to have a minor-league team, Trinidad was a hotbed of amateur and semipro baseball. There was even an Old-Timers League, and her father sometimes participated. In addition to watching the games, Ina loved the outdoors. She learned to ride a horse, and she also began to get involved in girls’ sports.

After graduating from Trinidad High School in 1900, she attended the University of Colorado at Boulder for two years. While there, she belonged to the fencing team and the girls’ basketball team. She got good grades in her courses, and she had begun writing about campus news for the Denver Post — her first experience with journalism.

But just before she left for college, Ina’s brother took seriously ill, and he never recovered; he died at the age of 17. He had been a very influential figure in her life, and she never forgot him. It was he who encouraged her to be more than just a baseball fan: He taught her the rules, familiarized her with baseball strategy, and showed her how to use a scorecard.11 At that time, most of the fans in Trinidad were men; a few women enjoyed and appreciated the game too, but to Ina’s disappointment, her mother was not one of them. Mrs. Young attended the games with Ina sometimes, but never seemed to understand the rules.12 Luckily, Ina had enough knowledge for both of them and could explain to her mother, or anyone else for that matter, the nuances of the game. She read every local newspaper account of baseball she could find, and she followed the national coverage in weekly publications like Sporting Life.13

Ina left college without graduating and returned to Trinidad determined to pursue a career in journalism. Her first full-time reporting job was at the Chronicle-News, where she was hired as a general reporter, which meant she covered everything from local stories to sports to social events. In 1904, while covering a strike at a nearby coal mine, she met the man who would later become her husband, Carlton A. “Mike” Kelley, who was a lieutenant in the unit of the National Guard called in to keep the peace.14 But while Ina was a good writer and had no problem with reporting hard news, her heart was set on being a sports reporter.

As luck would have it, when the 1905 baseball season was about to begin, the Chronicle-News found itself in a jam: None of the men who worked there had any idea how to keep a box score accurately, and most were not even baseball fans. Ina saw an opportunity; using the knowledge she had gained from her late brother, she offered to report on the games until the editor could find a man to do it.

Within a few weeks, it was obvious to the managing editor that Ina was the best person for the job, and she was encouraged to continue doing it. By 1906, she had been elevated to the position of “Sporting Editor,” as sports editors were called back then.15 In December 1907, when the prestigious journalism magazine The Editor and Publisher featured a profile about her, the writer noted that Ina was the only woman in the country doing this job. The profile also noted that she was reporting on football and horse racing, in addition to baseball. In fact, she told the writer that by that point, she had covered every sport except boxing.

Female sports reporters were rare in the early 1900s. The few we know about seem to have mainly covered women’s tennis or golf, especially if the players were celebrities or members of upper-class society. But in an era where gender roles were very specific, Ina Eloise Young had no problem being accepted as a baseball writer. In fact, there is no evidence that she endured discrimination — the closest thing she encountered was some skepticism from some of the older players.16 Yet it wasn’t long before she won them over with her knowledge of the rules and her appreciation of the game. And while at times her newspaper asked her to report on stereotypically female subjects like fashion or the women’s clubs, the editors were also willing to let her focus on sports, and they were genuinely proud of her accomplishments.17

Ina never saw herself as unique. She understood that most women of her day were not passionate about baseball, but she held out hope that others might eventually get hooked on the game the way she had.18 And even though she recognized that she was unusual, Ina did not see herself as a role model for women. It might be tempting to apply modern ideas of feminism to her, but the truth is that Ina was not in any way political. When she was interviewed by Bozeman Bulger, a reporter for the New York Evening World, she told him she had no interest in the women’s suffrage movement, and although women in Colorado could vote, Ina said she had never done so, nor did she intend to.19 “Boze,” a Southern gentleman from Alabama, wrote that he was delighted to hear she was opposed to women’s suffrage. He also referred to her as “pretty” and “dainty,” and he praised her for knowing sports while still maintaining her femininity — as if the two were mutually exclusive.

As mentioned, Trinidad was the perfect place for a sportswriter; it seemed as if the entire town was baseball-crazy. Fans came out in large numbers to watch their local semipro team, the Trinidad Big Six, named after a local bar and grill that was one of its sponsors.20 Some newspaper sources called it an amateur team, some said it was semipro, and some referred to it as a minor-league team, but by any name, it was a success. In 1907 the Big Six even won the state championship of Colorado.21 The team attracted some young up-and-coming players who hoped to land a position in the big leagues, and some players who were past their prime but still wanted to play. For example, one up-and-coming pitcher, Ralph Glaze, who went on to play for the Boston Americans (later known as the Red Sox), spent some time in Trinidad in 1905.22

One other interesting person who came to town went on to become a nationally known author and journalist: Alfred Damon Runyon. Runyon managed the Trinidad team at one point, and he also wrote articles about baseball for newspapers in Trinidad and Pueblo. By 1908, Runyon had been named president of the Colorado Baseball Association, and he was the master of ceremonies at Opening Day festivities when the Trinidad team opened its season at Central Park.23

By the summer of 1907 Ina’s work as a reporter was gaining her increased attention.The Denver Daily News featured a story about her, mentioning that she was not only a lady sporting editor in Trinidad but also the scorer for her team. “Her score books are pronounced perfect by all who have ever seen them … and visiting players to Trinidad have been much astonished at the accuracy with which she does her work,” the article noted.24

However, despite the praise, few of her articles were bylined yet — back then, it was still a custom that only the best-known writers (like the Boston Globe’s Tim Murnane or the Chicago Tribune’s Hugh S. Fullerton) got a byline, while everyone else wrote anonymously. But as her profile was raised — including the piece in The Editor and Publisher, which was picked up and reprinted in newspapers from coast to coast — it led to her finally getting a regular byline. Throughout 1908, most of what she wrote featured her name.

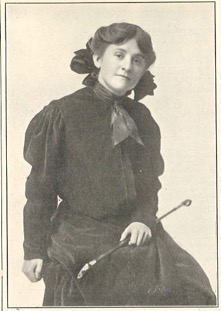

On the other hand, she did not write the headlines for all of her stories. That’s why some were typical of what any sports journalist would write (“Sporting Writer of This Paper Tells of Final Game”) and others reflected some rather gendered assumptions — a favorite of mine is “Enjoys Dresses and Hats as Well as World Series Games.” In fairness, Ina often was photographed wearing a lavish, brimmed hat, which was the style for women back then. Also, she sometimes did remark on what people in the crowd (especially the players’ wives) were wearing. However, this was never a central focus of her writing.

In this era before radio, many small-town and minor-league fans who followed major-league baseball depended on print publications to keep them up to date. When there was a World Series, some newspapers not only printed numerous editions, updating scores and game summaries every couple of hours; they also made the inning-by-inning scores available to the public by telegraph. Fans would gather outside the offices of their favorite newspaper, and as the telegraphers received the scores, a newspaper employee with a megaphone would announce them to the eagerly waiting crowds, or the scores would be posted on chalkboards outside. The Chronicle-News was among the publications that provided this service to the fans.25

But Ina’s newspaper did something more than that, something unusual for a city the size of Trinidad: Her editors sent her to cover the games in person, a tribute to the respect her newspaper and its readers had for her work. The Chronicle-News couldn’t help but brag about it; after all, few small-town newspapers sent a reporter to cover a World Series.26

Having successfully covered teams all over Colorado, Ina was ready to write about the Detroit Tigers and Chicago Cubs. Her thorough and insightful reports augmented reports from the Associated Press; her writing was crisp yet colorful, filled with interesting details about the crowds (or in the case of this World’s Series, the lack thereof), the ballparks, even the players’ wives. She noted, for example, that the wives of the Cubs players were a loyal group, who cheered for their men enthusiastically — they even carried large Cubs banners, and sometimes tooted horns.27

Ina did not seem awed by even the biggest names. For example, Ty Cobb had not done well in the 1907 Series, and although expectations for him were high, he had yet to impress. “The appearance of Ty Cobb,” she wrote on October 11, 1908, “is the signal for great screaming and groaning on the part of the Chicago people, and curiously, Cobb is again this year as little effective as he was last year.”28 Fortunately for Cobb and his fans, he had a much better game the next day.

That Sunday, October 11, Tim Murnane of the Boston Globe — a former player, and a widely respected sports reporter — was surveying the men sitting in the press box. But while noting the usual group of veteran reporters covering the Series, he saw someone unexpected: a woman. Known for being a gentleman, Murnane engaged her in polite conversation, but he obviously did not expect her to know baseball the way the veteran major-league writers did. However, Ina had encountered well-known baseball men before (including Hugh Fullerton and I.E. “Sy” Sanborn), and she was quite capable of having an in-depth discussion about the Series. Murnane came away highly impressed, writing in his syndicated column that “Miss Young proved an excellent scorer, was familiar with every inside play, and surprised me with the knowledge of the game.”29

Several days later, after the Cubs had won, a group of men gathered at Detroit’s new and elegant Hotel Pontchartrain to form the Baseball Writers Association. To her surprise (she was not in attendance at the meeting), Tim Murnane, who was named treasurer of the new organization, nominated Ina as an honorary member. The other writers, including new president Joe Jackson of the Detroit Free Press, agreed. She was also given a button that would identify her as a baseball writer and admit her to any American or National League ballpark.30 Praising the professionalism of the new association, she wrote that these sportswriters were “some of the finest men I have ever met.”31

Once her World Series assignment was complete, Ina did some traveling, partly to watch some college football games and report on them, and partly to visit some sports editors at newspapers in other cities. Among her stops was a trip to New York, where she met Bozeman Bulger of the New York World, and to Boston, where she met Albert (A.H.C.) Mitchell of the Boston American. While interviewing her, Mitchell remarked that Ina could “write sporting events as cleverly as most men.”32 He then asked her the two questions she said she got asked the most:

- Whether as a woman, she found male athletes to be rude and vulgar (one reason women were generally excluded from most occupations back then was the cultural belief that if they heard “bad language,” they might be horrified); and

- Whether a woman was suited for the position of sporting editor.

She told Mitchell that ballplayers had generally been very courteous to her, and that all they cared about was whether she knew and respected the game (she did) and whether she could score it fairly and accurately (she could). Of course, she said, she had met some rude and vulgar men, but most of the athletes she knew were gentlemanly around her, and she saw no reason why a woman who knows and loves sports couldn’t write about it successfully.

Ina continued with her career as a sportswriter for the next several years, traveling with the Trinidad baseball team when it was on the road, and writing about other sports when baseball was not being played; she also maintained her friendships with Hugh Fullerton and Sy Sanborn, visiting them and attending the 1911 World Series.33 But by that time, her personal life had changed. In March 1909 her father had died suddenly from a heart attack; a few months later, she left the Trinidad area and returned to Texas, where she still had friends and relatives. She went to work for the Fort Worth Record; by now, she was somewhat of a celebrity, and even the newspapers she didn’t work for wrote about what she was doing.

As it turned out, what she was doing was becoming engaged, and then getting married — on October 22, 1910, she wed Mike Kelley; she had known him since 1904. Kelley had an interesting story of his own: In college, one of his closest friends was Calvin Coolidge, the future president of the United States.34

Mike and Ina settled in Denver, where he completed his service to the National Guard and she wrote about sports for the Denver Post.35 She also was the scorer for Denver’s minor-league team, the Grizzlies, and a member of the executive committee tasked with overseeing all the league games in the region.36 Now known as Ina Young Kelley, she continued to write about baseball until mid-1912. At that point, she and her husband moved to Riverside, California, where they would spend the rest of their lives. Carlton Kelley became a purchasing agent for a power company. Ina retired from journalism, but every now and then she would write an article about sports or cover a local news story for one of the Riverside newspapers. She sometimes was a guest speaker for a civic organization, discussing her interesting years as a reporter.37

But as was common for married women of that era, she now focused her life on her family. She had two daughters, Kathleen, born in 1915, and Patricia, born in 1919. (Kathleen died from polio in 1946.) Ina became known in Riverside as a dedicated volunteer, raising funds for the local hospital and other worthy causes.

Ina Young Kelley died on May 2, 1949, at the home of her daughter Patricia in Arlington, Virginia. She and Carlton, who had died on July 13, 1947, are buried at Riverside’s Evergreen Cemetery.

When Ina died, despite her years of service to her adopted town of Riverside and her groundbreaking work as a baseball writer, there was only a short obituary in the Riverside Daily Press, one of the newspapers she had written for. If there were any obituaries in national sports publications, I have never found them. But someone with Ina’s unique accomplishments does not deserve to be forgotten. Today, women baseball writers are far more common than they were in the early years of the twentieth century. What Ina Eloise Young achieved set the stage for much of what came after — and for that, she deserves our thanks.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

The author would like to thank independent researcher Alice Romero and the reference staff at the Carnegie Public Library in Trinidad, Colorado, for their help.

Notes

1 In “C-N Only Colorado Newspaper That Has a Special Writer at World’s Championship Games,” Trinidad (Colorado) Chronicle-News, October 12, 1908: 1, her newspaper also claimed she was “the only lady sporting editor in the United States, or the world.”

2 “She’s Sporting Editor,” The Editor and Publisher, December 21, 1907: 11.

3 “A Woman Sporting Editor,” Denver Daily News, August 16, 1907: 9.

4 “She Writes Sporting Page,” Evening Missourian (Columbia, Missouri), December 16, 1909: 4.

5 Tim Murnane, “Attendance at World Series Below Expectations,” Duluth (Minnesota) News-Tribune, November 1, 1906: 2.

6 Ina Young Kelley, “Grizzlies Defeat Antelopes Second Time, Score 13 to 7,” Denver Post, April 21, 1912: III, 4.

7 “City Amateurs and Semi-Pros Open Schedule Today,” Denver Post, September 17, 1911: III, 2.

8 For example, in “She’s Sporting Editor,” The Editor and Publisher, December 21, 1907: 11, it says she is “only 24,” when in fact she was nearly 27.

9 “Colorado Official to Wed Texas Girl,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, October 7, 1910: 2.

10 Ina Eloise Young, “Petticoats and the Press Box,” Baseball Magazine, May 1908: 53.

11 “She’s Sporting Editor.”

12 Ina Eloise Young, “Petticoats and the Press Box.”

13 “A Feminine Tribute,” Sporting Life, March 28, 1908: 6.

14 “Girl Sporting Editor to Wed Colonel Kelley,” Denver Daily News, October 13, 1910: 16.

15 “A Feminine Tribute,” Sporting Life, March 28, 1908: 6.

16 Ina Eloise Young, “Petticoats and the Press Box.”

17 “Chronicle-News Lady Editor Highly Praised,” Trinidad Chronicle-News, August 17, 1907: 3.

18 Ina Eloise Young, “Petticoats and the Press Box.”

19 Bozeman Bulger, “Here’s a Woman Who Can Give Points to Fans,” New York Evening World, November 3, 1908: 5.

20 William A. Young, John Tortes ‘Chief’ Meyers: A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012), 16.

21“Trinidad Wins Pennant; Are Amateur Ball Champions of Colorado,” Trinidad Chronicle-News, September 16, 1907: 1; see also “Committee Formed to Pick 1908 Ball Team,” Trinidad Chronicle-News, October 14, 1907: 6.

22 “Glaze Pitched a Great Game,” Trinidad Chronicle-News, April 22, 1907: 1.

23 “Runyon May Be Head of League,” Trinidad Chronicle-News, February 8, 1908: 3.

24 “A Woman Sporting Editor,” Denver Daily News, August 16, 1907: 9.????

25 “World Series Ball Games at Chronicle-News Office,” Trinidad Chronicle-News, October 10, 1908: 3.

26 “C-N Only Colorado Newspaper That Has a Special Writer at World’s Championship Games,” Trinidad Chronicle-News, October 12, 1908: 1.

27 Ina Eloise Young, “Miss Young Tells of Scenes and Incidents in Detroit Game,” Trinidad Chronicle-News, October 16, 1908: 3.

28 Ina Eloise Young, “Graphic Description by Eye Witness of Sunday’s Big Game,” Trinidad Chronicle-News, October 14, 1908: 4.

29 Murnane.

30 Ina Eloise Young, “Sporting Writer of This Paper Tells of Final Game,” Trinidad Chronicle-News, October 17, 1908: 1, 9.

31 Ina Eloise Young, “Sporting Writer of This Paper Tells of Final Game,” Trinidad Chronicle-News, October 17, 1908: 9.

32 Ina Eloise Young, interviewed by A.H.C. Mitchell, quoted in “Women Should Be Editors of Sport,” Trinidad Chronicle-News, November 7, 1908: 3.

33 “Short Sport Bits,” Omaha World-Herald, October 15, 1911: 3-S.

34 “Riversider Intimate Friend of Coolidge,” Riverside (California) Daily Press, January 5, 1933: 12.

35 Ina Young Kelley, “Grizzlies Defeat Antelopes Second Time, Score 13 to 7.”

36 “City Amateurs and Semi-Pros Open Schedule Today,” Denver Post, September 17, 1911: III, 2.

37 “Newspaper Woman Talks to Lions,” Riverside Daily Press, March 15, 1932: 3.

Full Name

Ina Eloise Young

Born

February 22, 1881 at Brownwood, TX (USA)

Died

May 2, 1949 at Arlington, VA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.