Jack Tobin

He was always Johnny Tobin in St. Louis but is listed in standard reference sources as Jack, which he was occasionally called on the road. Contemporary news coverage and players who knew him invariably called him Johnny. Tobin played his first 11 seasons in the major leagues for hometown teams – first the Federal League’s St. Louis Terriers and then the American League’s St. Louis Browns. And in 1915, when there were three major-league baseball teams in St. Louis (including the National League Cardinals), Johnny Tobin was the only native on any of the three teams.

He was always Johnny Tobin in St. Louis but is listed in standard reference sources as Jack, which he was occasionally called on the road. Contemporary news coverage and players who knew him invariably called him Johnny. Tobin played his first 11 seasons in the major leagues for hometown teams – first the Federal League’s St. Louis Terriers and then the American League’s St. Louis Browns. And in 1915, when there were three major-league baseball teams in St. Louis (including the National League Cardinals), Johnny Tobin was the only native on any of the three teams.

His father, John, a bricklayer, had come to the United States from Ireland in 1870. In Missouri, the father met his future wife, Louise Schiffner, three years younger, a native of the state born to immigrant parents – a German father and an Irish mother. Their first-born was a daughter, Sadie Tobin, born in March 1889, followed by John on May 4, 1892. There were two later sons, Maurice and James, and another daughter, Margaret. The elder John Tobin apparently also did some contracting work, and even worked for a while in New Orleans when Johnny was young. [1]

John Thomas Tobin attended school for eight years at St. Malachy’s, a Catholic elementary school in St. Louis. He was never a large man, giving his height as 5-feet-8 and playing weight as 142 pounds. Tobin played a lot of amateur baseball in the area from 1909 through 1912 for teams such as the St. Rose’s, Mount Olive, Alton, and East St. Louis (as best we can determine from handwritten notations on a form filled out for the Federal League.) He began as a pitcher, but converted to an outfielder before 1914 began.

There is a little uncertainty about when Tobin first began playing baseball in earnest, but sources place his major-league debut as April 16, 1914, Opening Day for the St. Louis Terriers season against the visiting Indianapolis Hoosiers. The Terriers’ home field was Handlan’s Park, and the manager was Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown, the former Chicago Cubs pitcher now in the Hall of Fame. The Hoosiers built a 7-3 lead over St. Louis; Tobin’s moment came in the bottom of the ninth, when he pinch-hit unsuccessfully for pitcher Bob Groom.

Tobin had actually started his professional career twice earlier. The first contract he signed was with the Texas League’s Houston Buffaloes, but he never reported to the team and was released.[2] Next, he signed with the St. Louis Terriers in 1913, one of six teams in the independent Federal League playing for manager Jack O’Connor. He was working as a lineman for Bell Telephone in 1913 when O’Connor and team owner Otto Stifel heard that there was a good player right in town, playing for the phone company team. When they sought him out, they found him perched on a telephone pole. A workout the next day convinced them of his skill as a batter and they signed him up.[3] Skimpy records in the Hall of Fame show Tobin as playing in 41 games and collecting 42 hits in 124 at-bats, which would compute to a .339 batting average. When the league expanded to eight teams in 1914 and became considered a major league, Tobin was a regular.

One thing Tobin took care of between seasons was to get married, on March 4, 1914, to Loretta M. Sack. The couple eventually had one child, Dorothy Louise Tobin, in 1916.

The Terriers had two managers in 1914, Mordecai Brown and Fielder Jones, reflecting their status as the last-place team in the league. Some saw the Federal League team as an assemblage of has-beens, former players not quite good enough to make either of the two established leagues. At the age of 22, Tobin was one of the youngest players on the team, but held his own, getting in 139 games and batting .270, third best on the team. Despite his smaller stature, his seven home runs led the team. It didn’t take long before he was noticed; a headline in the April 28 St. Louis Post-Dispatch read, “BROWN DISCOVERS A REAL STAR IN OUTFIELDER TOBIN.” After the first seven games against Indianapolis, one of the Hoosiers said Tobin was one of the top two outfielders in the league. And he did have some power. His June 6 homer over the left-field wall in Kansas City was “one of the longest hits ever made in the local park.”[4] It wasn’t the home runs that caught the imagination. Sportswriter W.J. O’Connor observed that “the speedy right fielder” was “playing the snappiest ball of the local club. He has a good arm, speed and can hit. He shows an inclination to try something new, in the way of swinging bunts and delayed steals, and he has such a hold on the fans that they will resent any attempt to bench the youngster.”[5]

One of the more astonishing games in big-league history took place on June 16. The Brooklyn Tip-Tops were in town and scored three runs in the top of the first, only to see St. Louis promptly tie the game. Brooklyn took a 5-3 lead with two in the eighth, but the Terriers tied it, 5-5, in the bottom of the ninth. The game went into the 12th and it looked as though the Tip-Tops were determined to wind up on top, scoring seven runs and taking a 12-5 lead. Tobin was up first in the bottom of the 12th and he hit a home run. The team batted around and he came up a second time with the Terriers trailing 12-10. There was still only one out and the bases were loaded. Tobin singled, driving in the sixth run of the inning for St. Louis. The next batter, Ward Miller, walked to force in the tying run, and the batter after that singled, giving St. Louis a 13-12 win.

For the second time in two months, W.J. O’Connor proclaimed Tobin a real “find” for the Feds. Only Tobin and Henry Keupper had been kept from the 1913 team, and Keupper’s 8-20 record didn’t keep the southpaw in work after 1914. O’Connor noted Tobin’s success with the bunt; his speed also helped him – once Fielder Jones (who had managed the “Hitless Wonder” 1906 White Sox) began to tutor him – become a better basestealer.[6] Both of St. Louis’s other teams in the persons of Branch Rickey (Browns) and Miller Huggins (Cardinals) tried to sign Tobin, but he began 1915 working on a new $4,000-a-year contract, signed for both 1915 and 1916.[7]

Havana, Cuba, hosted the Terriers for spring training in 1915 and Tobin was singled out for an invitation to come to Cuba at the end of the year and play winter ball, though he didn’t do so. The 1915 season saw the Terriers rocket to the top of the league standings. After finishing last, 25 games out of first place, in 1914, they climbed all the way to a near-tie with the Chicago Whales in 1915, finishing at .565 to Chicago’s .566 (the Terriers played two more games than Chicago, winning one and losing one, and that .500 split of the extra pair cost them in winning percentage.) Tobin covered up a serious injury to his thumb in the early going against the Brooklyns and led the league in hits with 184 and finished with a .294 average, up from.270 in 1914.

The Federal League met its demise after the two seasons as a major league, and players tried to catch on where they could. The Terriers recouped some of their investment by selling Tobin’s contract to the St. Louis Browns on February 10, 1916. It helped that Phil Ball, one of the principal backers of the Federal League club, had become head of the Browns. (Ball also hired Fielder Jones as manager.) There was a decision to be made in the springtime between keeping Tobin or three-year Browns veteran Tillie Walker to play right field. The team went with Tobin, and Tillie was sold to the Boston Red Sox on April 8.

There was a City Series of sorts in 1916 between the Browns and the Terriers, who hadn’t given up the ghost yet, and now it was Tobin for the Browns facing his old team. In the two games, Tobin was 4-for-8 and stole a base. He and outfielder Armando Marsans drove in six of the 11 runs. Despite the help of the “reformed Federal Leaguers,” the Browns still went down to defeat.[8] Tobin was, in the words of The Sporting News, “about the only player who really was developed ‘from the ground up’ by the late Federal League.” [9]

After the season got going, Tobin got off to a poor start for the Browns, getting only two hits in 16 early at-bats and resulting in some time on the bench for him and some playing time for Ward Miller in right. On August 5, it was announced both Tobin and pitcher Tim McCabe were transferred to Nashville, to report on the 12th but manager Fielder Jones denied the story two days later: “With the club going as it is, I need all the reserve strength I can get.”[10]

The team was in sixth place, but it was a tightly-bunched race and even the seventh-place Senators were only eight games out of first. Tobin’s average fell dramatically, to .213. He was the team’s fourth outfielder, behind Miller, Armando Marsans, and Burt Shotton, and he appeared in only half of the team’s games.

At season’s end, there was need for a little advance spring cleaning and on November 16, Business Manager Branch Rickey announced the release of six players. Tobin was sent to the Salt Lake City team on option until the fall of 1917. Playing in the Pacific Coast League for the Bees was apparently agreeable; Tobin had an even 800 at-bats (the Coast League played longer seasons, and Tobin appeared in 189 games), batting .331 for the year with a league-leading 265 hits (all but 47 of them singles, and often via the adept execution of the drag bunt). His average placed him second in the league at batting. The 149 runs he scored were 20 more than the second-place man. He got on base a lot. Years later, in his obituary, unnamed “experts” were said to have averred, “There was no one in the history of the game who was better at dragging a bunt.”[11] One of the experts may have been Browns teammate George Sisler, who appraised Tobin for sportswriter Bob Broeg. “One of the best leadoff men I ever saw. …He was fast and a good outfielder with a strong throwing arm and, above all, he was the best drag-bunter anyone ever saw. It was uncanny the way he could drag the bunt just past the mound, too far over from the pitcher and too soft for the second baseman to make a play.” In the same column, Broeg quoted Tobin, talking with a twinkle in his eye, as saying, “I was a .330 hitter most of my career. I’d bat .030 and bunt .300.”[12]

Tobin was again one of four outfielders pegged for spring training in 1918, but he still had to prove he could play in faster company. The feeling was that he’d suffered an injury of sorts in 1916. Manager Fielder Jones, quoted in the March 5 Post-Dispatch, assessed Tobin’s season in Salt Lake as a great one, adding, “I rather figure he has come back and found himself again. He fell down badly when with us before, but that wasn’t because he was lacking in ability. His confidence was injured here and he never regained it.”

In mid-April, the Browns swept the City Series from the Cardinals in four straight games. And he did indeed rebound with the Browns in the war-abbreviated 1918 campaign. He got off to a terrific start, even pacing first baseman George Sisler for the first couple of weeks. He enjoyed some key games – singling in the final run of a four-run rally in the ninth to beat the Yankees on May 18, and throwing out a runner at home plate to end the game and prevent Washington from tying the score on July 20. And he finished the season hitting .277.

It was in 1919 that Tobin truly began to shine; he hit .327, which saw him second only to Sisler on the Browns and ranked him sixth in the league. It was an average Tobin bumped up each of the next two seasons –.341 in 1920 (Sisler hit .407) and .352 in 1921. The latter year was Tobin’s best, and included 236 base hits, among which were a league-leading 18 triples, an on-base percentage of .487, and 132 runs scored (second in the American League).

Tobin turned 30 in 1922 but came in with another excellent year, hitting .331 in the best season the Browns had in the era. They fell just one game short of winning the pennant, bowing to the Yankees, against whom they were 8-14 that year, the only team against which they had a losing record. Browns batters won the Triple Crown, Sisler hitting a sizzling .420, while left fielder Ken Williams led the league in homers (39) and RBIs (155). Urban Shocker (24-17) was their leading pitcher, his 149 strikeouts also leading the league. On August 6, Tobin hit a grand slam off Washington’s “Big Train,” Walter Johnson. He always said his biggest thrill was hitting two slams off Johnson, but if he hit another bases-loaded homer off Johnson, it must have been during an exhibition game.

Johnson respected Tobin greatly as a resourceful hitter:

In these days when nine out of every 10 batters simply takes a healthy swing, Johnny Tobin stands out as one of the few batters who mixes them up, keeps the pitcher uneasy. Tobin is fast, is an excellent bunter and perhaps the best man in the American League dragging the ball down the first-base line. Nothing tends to upset a pitcher more than to have a player unexpectedly drag the ball and get away with it. The maneuver also tends to make the whole team wobble on defense. Tobin, however, doesn’t confine his hitting to mere bunting or dragging the ball. He can pull a ball into right field with great force, and can poke a fast one on the outside into left field with uncanny deftness. Tobin is a batter of the old school, not unlike Willie Keeler in many respects. I am glad there are not more like him.[13]

There was talk before the 1923 season that the Browns had some top-flight new prospects and that Tobin might find himself on the bench. He confounded the early dope, and produced a career-high 73 RBIs; his average fell to .317, still more than respectable by any measure. For the second year in a row, he hit 13 home runs, his career best.

By March 1925, as the St. Louis contingent left Missouri for spring training in Tarpon Springs, Florida, Tobin was placed in charge of the traveling party, seen as one of the veterans and a leader on the club.[14] In 1924, he put up his first sub-.300 season since 1918, though he was shy by only one point (.299). In response, he had his teeth taken out. Apparently. Washington Post columnist John D. Sheridan commented, “Tobin can do more different things with a baseball bat than any man I have ever seen. I have seen him lay down and beat out a perfect bunt, then next time up whip one over the right-field fence. Neither Burkett nor Keeler could pull a ball over any fence. …. The trouble with Tobin is that he uses his head merely as a knot to keep his body from unraveling. If Johnny ever gave hitting a thought he would be one of the greatest hitters of all time.”[15]

The following year, 1925, the point was on the plus side of .300 – Tobin batted .301, but he appeared in only 77 games; Harry Rice was hitting .359 and playing a good right field. It would have been difficult to deny him.

Rumors of a trade to Washington began to circulate in the fall of 1925. They became reality on February 1, 1926, when the Browns acquired two pitchers from the Senators (Tom Zachary and Win Ballou), giving up veterans Bullet Joe Bush and Johnny Tobin. The Senators had made somewhat of a specialty out of taking on players who could benefit from a change of scenery, and squeezing one more good year out of them. There wasn’t a lot of room in the outfield for Johnny, however, with three .300 hitters in Sam Rice, Goose Goslin, and Earl McNeely. And reserve outfielder Joe Harris hit well enough in the springtime that Tobin was behind him on the depth chart.

Tobin was “slowing up and slipping backward,” said manager Bucky Harris, though the skipper allowed, “There is still lots of good baseball in his system.” Tobin was batting only .212, however, with just one extra-base hit in 33 at-bats. He was placed on waivers, and all the other teams passed. On June 29, Washington gave him his unconditional release, leaving him free to sign with any club. Just the week before, Tobin had moved his family from St. Louis to Washington.[16] He had an automobile dealership in St. Louis, and gathered up his family and returned there, the July 1 Post reported.

President Bob Quinn of the Red Sox offered Tobin a spot on the Boston ballclub, but Tobin wanted to go home to Missouri to think things over. A few weeks later, the offer still stood and it was announced on July 20 that Tobin would joined the Red Sox on the road in Cleveland. Ira Flagstead’s broken collarbone offered a fortuitous opportunity to get in more work than Tobin otherwise might have had, and he responded. In his first game, Johnny had a 3-for-5 day, driving in four runs. In his first nine games, he had six multihit games. There was no way he was going to maintain that pace, but he did hit a solid .273. And he had the chance to wreak a little revenge on the Browns, hitting a grand slam in Sportsman’s Park on September 12, all the runs the Red Sox needed for an 11-3 win.

In 1927, Tobin had one last season in the majors, hitting a very good .310 as the regular right fielder for the Red Sox. He was given his outright release on January 27, 1928. He finished with a lifetime .309 major-league average. One wonders if there had been some failure to communicate or not. The Associated Press report said that when Tobin signed on with the Red Sox in 1926, it was “with the understanding he would be released should he decide to enter business. He has not been heard from this winter and his name was dropped from the list when the roster was completed today.”[17] It wasn’t that he didn’t want to play baseball, though his age – he was now 35 – may have played a factor as well. On February 17, Tobin signed with the American Association’s Columbus Senators.

In 53 games for Columbus, Tobin played first base and hit .285. He saw pretty limited action with the Browns-affiliated Wichita Falls Spudders in 1929, but batted 1.000 – three hits in three at-bats, two of them doubles. And in 1930, he was player/manager for the Bloomington Cubs, hitting .310 in 29 at-bats.

Tobin then returned home to the St. Louis area, living most of the time in the town of Lemay, just south of St. Louis. He did a little coaching around the area and served as captain of the Fire Department at the Army’s Jefferson Barracks in the middle to late 1940s. From 1944 through 1951, he was a major-league coach for the St. Louis Browns. In early 1949, he was asked to tutor the younger players in the art of bunting. Browns General Manager Charley DeWitt said, “We finished in sixth place in 1948 by getting 59 victories. But do you know that we lost 28 games by a single run when we couldn’t put over the squeeze play or a sacrifice. A perfect bunt at the right time would have won a lot of those games.”[18] It wasn’t always the most rewarding of work, Tobin told The Sporting News. “Nobody wanted to work too hard at bunting and if you’re going to be good at it, you really have to work. … Everybody wanted to swing for the fences.”[19]

After Tobin’s coaching days were done, he contented himself with managing semipro teams in St. Louis’s Municipal Baseball Association. He managed a team called the Red Villas and won three pennants in four years, finishing second the other time. “Should have made it four straight,” the competitive Tobin asserted.[20] Grandson Tim Brady said that Tobin also represented a distillery for a while and did some work in the automobile business, as well as having much more time to enjoy his beloved hunting and fishing. Tobin was named as one of the outfielders on the All-Time All-Star St. Louis baseball team in January 1958 by the Baseball Writers Association of America, keeping company with Stan Musial, George Sisler, Frankie Frisch, Rogers Hornsby, Dizzy Dean, and Red Schoendienst.

Tobin died of pneumonia on December 10, 1969, survived by his wife and daughter and two brothers.

Sources

Special thanks to Tobin’s grandson Tim Brady, who inspired this biography. Thanks as well to Bill Rogers, Roger Godin, and Fred Heger.

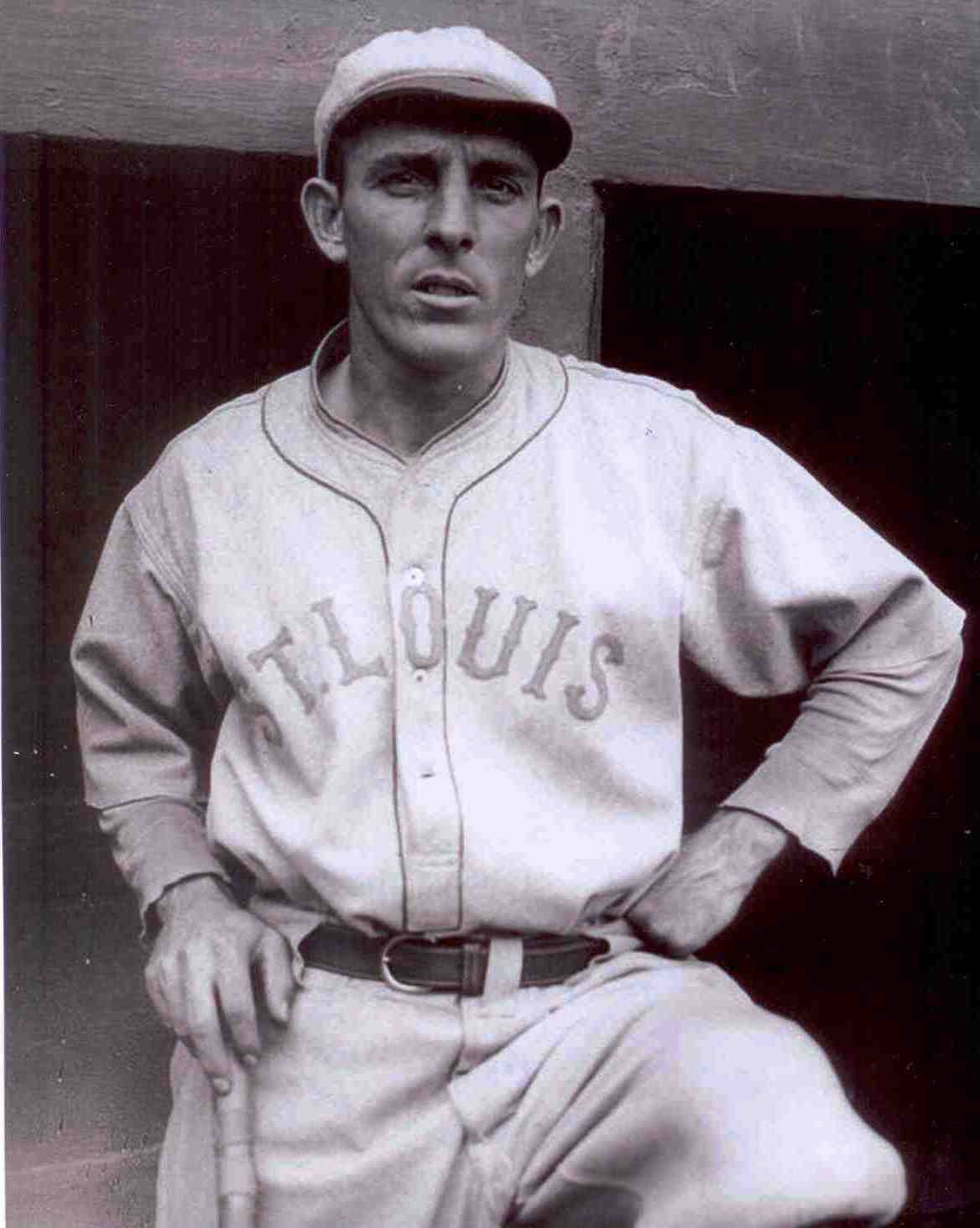

Photo Credit

Tim Brady

[1] E-mail correspondence from Tobin’s grandson Tim Brady, February 17, 2010.

[2] The Sporting News, February 14, 1962. The February 3, 1916, Sporting News reported that Tobin had signed with Fort Worth earlier in 1914 but jumped the club.

[3] St. Louis Globe-Democrat, February 20, 1949.

[4] St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 7, 1914..

[5] St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 10, 1914.

[6] St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 18, 1914, and April 20, 1915

[7] St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 3 and March 16, 1915

[8] St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 10, 1916.

[9] The Sporting News, January 17, 1918.

[10] St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 7, 1916.

[11] The Sporting News, December 27, 1969.

[12] St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 11, 1969.

[13] The Sporting News, February 7, 1924.

[14] New York Times, March 3, 1925.

[15] The Sporting News, April 9, 1925.

[16] Washington Post, June 30, 1926.

[17] Hartford Courant, January 28, 1928.

[18] St. Louis Globe-Democrat, February 17, 1949.

[19] The Sporting News, December 27, 1969.

[20] The Sporting News, February 14, 1962.

Full Name

John Thomas Tobin

Born

May 4, 1892 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

December 10, 1969 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.