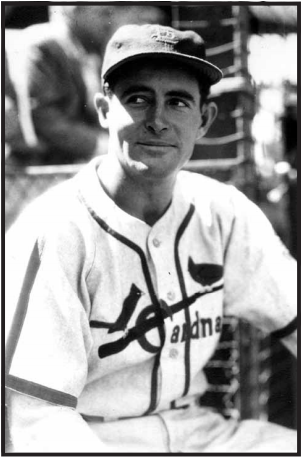

Jack Creel

Pitcher Jack Creel overcame a birth defect to enjoy a 16-year career in professional baseball. “If my father laid his hands out on a table, he could not straighten his fingers out,” the player’s son, Jack Creel, told the author. “His fingers were in a shape of a baseball all of the time. He tried to enlist in the Army, but he couldn’t salute because his fingers were so crooked.”1 Consequently, Creel was designated 4-F (unfit for military service) and did not serve in World War II. Ironically, his deformed fingers probably helped him land a spot on the St. Louis Cardinals in 1945 when the reigning World Series champions were in desperate need of pitching. Creel’s tenure in the big leagues was confined to that one season and a 5-4 record, but the good-natured Texan won 179 games and logged more than 2,800 innings in the minor leagues.

Pitcher Jack Creel overcame a birth defect to enjoy a 16-year career in professional baseball. “If my father laid his hands out on a table, he could not straighten his fingers out,” the player’s son, Jack Creel, told the author. “His fingers were in a shape of a baseball all of the time. He tried to enlist in the Army, but he couldn’t salute because his fingers were so crooked.”1 Consequently, Creel was designated 4-F (unfit for military service) and did not serve in World War II. Ironically, his deformed fingers probably helped him land a spot on the St. Louis Cardinals in 1945 when the reigning World Series champions were in desperate need of pitching. Creel’s tenure in the big leagues was confined to that one season and a 5-4 record, but the good-natured Texan won 179 games and logged more than 2,800 innings in the minor leagues.

Jack Dalton Creel was born on April 23, 1916, in Buda, then a small town (and now a commuter suburb) located about 13 miles southwest of Austin, Texas. His parents, Alford and Nora Creel, were both originally from nearby Kyle, and like most of the neighboring families were farmers. According to the player’s son, Creel attended Buda’s Hays High School, but left after the ninth grade as the increasingly harsh economic conditions of the Great Depression required the teenager to work and help support the family. By the time Creel was 16, he was playing baseball on town and semipro teams in Buda and Kyle, and also in San Marcos, where he was a teammate of his cousin the future big-league pitcher, Tex Hughson. Despite his fingers, J.D. (as he was often called) began as a third baseman and outfielder, and was later moved to the mound because of his strong right arm.

In 1938 the 22-year-old Creel began his 16-year career in Organized Baseball with the Taft (Texas) Cardinals in the inaugural season of the re-formed Texas Valley League. The rookie acquitted himself well with a team-best 15 wins and 3.79 ERA (in 183 innings); he also occasionally played in the outfield and batted .253. When the league disbanded at the end of the season, the Houston Buffaloes, the St. Louis Cardinals’ affiliate in the Class A1 Texas League, purchased Creel’s contract.2 They assigned him to the New Iberia (Louisiana) Cardinals of the Evangeline League, one of the Cardinals’ 16 Class D affiliates in 1939. Creel (15-11) along with 18-year-old phenom Howie Pollet (14-5) led New Iberia to the league championship series, which the team lost in seven games.

Cardinals president and GM Branch Rickey had built a minor-league farm system unparalleled in baseball history. By 1940 the empire consisted of 31 teams with more than 700 players (including more than 200 pitchers) on the “chain gang,” a derisive term commonly used to describe the shackled and indentured feeling of so many of the players under contract. With a surfeit of pitching prospects, a player needed luck and timing just to move up a class. Creel began the 1940 season with the Columbus (Georgia) Red Birds of the Class B South Atlantic (Sally) League. After a few rough outings and with the deadline approaching for teams to reach the 16-player roster limit, Creel was reassigned to the Daytona Beach Islanders, yet another Class D team, in the Florida State League. Creel and his roommate, a 19-year-old southpaw and hot prospect in his third year of Class D ball, Stan Musial (18-5), formed the circuit’s best righty-lefty duo. Described by The Sporting News as a “fastballer,” Creel won a career-high 22 games, including ten in a row in midseason, completed 23 of 28 starts, and posted the league’s best ERA (1.51).3 Creel, nicknamed “Texas Jack” and “Tex,” possessed impeccable control, issuing just 44 walks in 245 innings. “[Creel is] largely responsible for the Islanders’ first pennant in five years,” wrote The Sporting News.4 Musial and Creel also regularly played in the outfield (57 and 38 games respectively); however, an arm injury ended Musial’s pitching career and a .209 average in 235 at-bats terminated Creel’s outfield aspirations.

In 1941 Creel went from the lowest minor-league classification to the highest when he was promoted to the Columbus (Ohio) Red Birds of the American Association, one of the St. Louis Cardinals’ traditional springboards to a big-league career. But the 25-year-old had little chance to crack a starting rotation anchored by future big leaguers Harry Brecheen, Murry Dickson, Preacher Roe, and hard-throwing Johnny Grodzicki. After 11 relief appearances, Creel was sent back to Columbus, Georgia, to play in the Sally League.

Sold to the Houston Buffaloes in the Class A1 Texas League in the offseason, Creel enjoyed being close to home and pitching in the scorching, unforgiving climate in 1942. For a fifth-place club, he went 13-6 and posted a stellar 1.92 ERA in 197 innings as a starter and reliever.

Creel spent the following two seasons, 1943 and ’44, with Columbus in the American Association during a time when the parent club saw its roster increasingly depleted by the war. A fifth starter behind Ken Burkhart, George Dockins, Preacher Roe, and Ted Wilks, Creel won just eight of 21 decisions and posted a disappointing ERA (3.99) in 185 innings for the league and Junior World Series champions. Despite an 11-15 record and 4.25 ERA (highest among starters on the team) in 1944, Creel was acquired by the St. Louis Cardinals at the conclusion of the season.

An even 6 feet tall, Creel was willowy and weighed about 165 pounds. Good-looking with wavy, coal-black hair and brown eyes, the easy-going Creel was known as much for his big smile as he was for his modest personality. Friends and teammates (especially during his years in the Texas League) affectionately called him the “Squire of Buda, Texas.” He married Francis Lucille Capps, from Kyle, Texas, and had two children, Jack and Kaye. His son recalled that his father was a superstitious player who often told a story about leading late in a game while pitching for Houston when a black cat suddenly ran in front of home plate. The pitcher came unraveled and lost the game. “My father loved to go to the traveling carnivals and play games,” said his son with a laugh. “They finally banned him and wouldn’t let him throw at the bottles or anything else because he kept winning everything.”

Creel joined St. Louis at the Cardinals’ spring-training camp which due to wartime travel restrictions was held in Cairo, Illinois, 150 miles southeast of the Mound City. The reigning three-time pennant winners and 1944 World Series champions had lost pitchers Johnny Beazley, Al Brazle, Murry Dickson, Howie Krist, Red Munger, Pollet, and Ernie White to the war. “I have a better pitching staff in the service than [manager] Billy Southworth can put on the field,” said Cardinals owner Sam Breadon.5 Creel, Burkhart, and Dockins were expected to pick up the slack. “He has everything to he needs to be a winner in the majors,” said Southworth about Creel during camp.6

Relegated to the far end of bullpen as the 1945 season commenced, Creel made his big-league debut on April 22, 1945, by tossing one scoreless and hitless inning of relief in a Cardinals loss at Sportsman’s Park. He picked up his first win on May 15 despite yielding three hits, two walks, and a run in two innings in a slugfest with the Boston Braves. But the following day the Texan “showed amazing stuff” by holding the Braves to just one hit over 7⅓ innings of relief in Boston.7 Creel’s showing occurred at an opportune time: The Cardinals were on the verge of losing two starters, Max Lanier (to the war) and Mort Cooper (traded to the Braves), while starters Brecheen and Wilks were fighting arm pain.

The 29-year-old Creel finally got his chance. With the Cardinals struggling and just a game over .500, Creel tossed a six-hitter to defeat the Brooklyn Dodgers, 11-1, on May 23 in his debut start. Described as a “great competitor” and “smart” by syndicated writer Frederick G. Lieb, Creel won two of his next three starts to push his record to 4-1 accompanied by a 2.30 ERA.8 An Associated Press report praised Creel for being “cool under fire” and noted that he “takes plenty of time between pitches.”9 But Creel struggled in his next three starts and was ushered back to the bullpen. Given a spot start on July 19, Creel was forced to leave the mound in the seventh inning with excruciating pain in his shoulder. He returned three weeks later, but made only five relief appearances between August 11 and September 3, when he was shut down for the season. Plagued with shoulder pain for the rest of his career, Creel was never the same pitcher after the injury. In his sole season on the big stage, Creel won five of nine decisions and posted a 4.14 ERA in 87 innings.

An early cut from the Cardinals camp in 1946, Creel was assigned to Columbus in the American Association, which had been reclassified to Triple-A status during a reorganization of the minor leagues. He suffered from “sore muscles in his pitching arm” throughout the campaign and struggled with his control, once walking ten in a complete-game, two-hit loss.10 A disappointing 8-11 record from the Texan whom the team considered to be “a sure-fire ace” resulted in his demotion to Houston in the Texas League in the offseason.11

Creel spent the next three seasons (1947-1949) with the Buffaloes in what became his adopted hometown of Houston. In his second stint with the club, he “made a sensational start on the comeback trail.”12 He tossed 25⅓ consecutive scoreless innings, earning praise as “a fan’s dream pitcher [whose] picture curve and live fastball draw ‘ohs’ and ‘ahs’ from the crowd” in Buffalo Stadium.13 With a 14-10 record and a stellar 2.63 ERA in 250 innings, Creel teamed with pitchers Clarence Beers (25-8) and Al Papai (21-10) to lead Houston to the league title and the 1947 Dixie Series championship over the Mobile Bears of the Southern Association.

After a 12-10 season marred by back pain in 1948, Creel had an offseason elbow operation to remove bone chips.14 He recovered sufficiently to earn an invitation to the Cardinals’ spring training from Houston native Eddie Dyer, who had skippered the team since 1946. With the sale of workhorse Murry Dickson to the Pittsburgh Pirates in the offseason, Dyer envisioned Creel as an ideal reliever.15 It appeared as though the 33-year-old had won a spot on the club when the Cardinals broke camp in Phoenix en route to St. Louis. However, when the team arrived in Houston to play the Buffaloes, Dyer informed the hopeful hurler that he didn’t make the team.16 Assigned to the Buffaloes, the elder statesman on the staff overcame his disappointment to pace the team in wins (16) and logged in excess of 200 innings for the fourth and last time in his career. Having played most of his career in the Deep South, Creel enjoyed pitching in hot weather. “He often pitched on Sundays,” reminisced his son in an interview with the author. “I remember how my mother would always make fried chicken before those games, then he’d go and pitch. He could handle the heat.”

After two seasons with the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League (1950-1951), Creel was back with Houston in 1952. At 36 years of age, he was slowing down and had been gradually converted to a reliever by manager Bill Sweeney in Portland. After appearing in a career-high 44 games (including nine starts) and posting a 6-12 record for the last-place Buffaloes, he announced his retirement at the conclusion of the season. But former Buffaloes president Allen Russell, who had purchased the Beaumont (Texas) Exporters of the Texas League after the 1952 season, lured the aging hurler out of retirement. On a talent-poor, last-place team, Creel was moved back into the starting rotation. An 8-15 record and 5.20 ERA in 166 innings signaled that Creel had reached the end of the road.

Creel participated in the Exporters’ spring training the following season, but retired before the start of the season. The fun-loving Texan posted a 179-159 record, logged 2,804 innings, and appeared in 516 games during his 15 years in the minors. “He never made much money playing baseball,” said his son, “but he loved it.”

For 16 years Creel had zigzagged across the country, going from one spring training and team to another, his wife and children always in tow. But he was ready to settle down permanently in Houston, his offseason home since the late 1940s. With experience as a pipefitter in oil fields, Creel enjoyed a long and successful career as a salesman for Valley Steel and later Metcoat Paint in Houston.

According to his son, Creel was a natural athlete who picked up sports easily. He was an avid hunter, an enthusiastic golfer, and an expert in horseshoes, washers (a game similar to beanbag in which the player tries to throw metal objects into tall cylinders), and ping-pong. He also enjoyed playing the accordion and harmonica, and was a well-known tomato gardener.

After his playing days, Creel remained close with the Houston Buffaloes. He regularly participated in old-timer’s games and various reunions. He maintained friendships with several Buffalo teammates, including Clarence Beers, Billy Costa, Solly Hemus, and Jerry Witte. He also coached his son’s youth league baseball team and occasionally conducted baseball clinics in the early 1950s.

Jack Creel died of natural causes at the age of 86 on August 13, 2002, in Houston. He was buried in Memorial Oaks Cemetery.

Sources

The Sporting News

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.com

SABR.org

The author interviewed Jack Creel (player’s son) on March 11, 2014.

Notes

1 The author extends his gratitude to Jack Creel, the player’s son, for his interview conducted on March 11, 2014. All quotations from the son are from this interview.

2 The Sporting News, February 16, 1939, 6.

3 The Sporting News, September 5, 1940. 7.

4 The Sporting News, October 17, 1940, 8.

5 The Sporting News, May 31, 1945, 8.

6 Ted Meier, “Pirate Hopes Decline With Draft Reports,” Burlington (North Carolina) Daily Times-News, April 4, 1945, 6.

7 Jack Hand, “Embarrassed Cards Slip to Fifth,” Mason City (Iowa) Globe-Gazette, May 17, 1945, 13.

8 The Sporting News, June 7, 1945, 8.

9 Associated Press, “Jack Creel Second Big League Hill Find Contributed by Tiny Kyle, Texas,” Athens (Ohio) Sunday Messenger, June 3, 1945, 9.

10 The Sporting News, June 12, 1946, 20.

11 Ibid.

12 The Sporting News, May 7, 1946, 28.

13 The Sporting News, May 21, 1946, 27.

14 Associated Press, “Buff Hurler Gets Arm Operation,” Abilene (Texas) Reporter-News, January 30, 1945, 5.

15 The Sporting News, February 9, 1949, 4.

16 Associated Press, “Jack Creel Back With Houston Nine,” Galveston (Texas) Daily News, April 10, 1949, 13.

Full Name

Jack Dalton Creel

Born

April 23, 1916 at Kyle, TX (USA)

Died

August 13, 2002 at Houston, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.