Jack Fisher

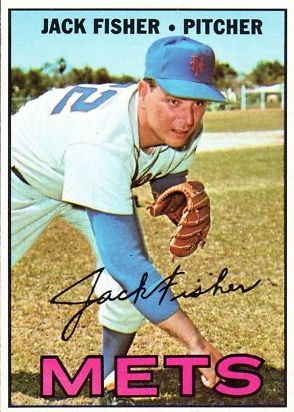

Jack Fisher, a pitcher whose lowly won-lost record was a poor indicator of his ability and endurance, earned a place in baseball history, if not on the list of its immortals, by being on the wrong end of two of the game’s most famous home runs. At 21, he finished up his second season in the majors by serving up the final home run of Ted Williams’s career. The following season the young right-hander was the victim of Roger Maris’s 60th home run, the blast that tied Maris with the immortal Babe Ruth. And yet while those episodes may be the events that have made Fisher a permanent historical footnote, his 11-year career was notable for far more than that. Indeed, while success often eluded him, his efforts on often hapless teams and in difficult situations earned him the respect of teammates and baseball professionals alike, while endearing him to fans who appreciated the consistent efforts of Fat Jack, as he was popularly known.

Jack Fisher, a pitcher whose lowly won-lost record was a poor indicator of his ability and endurance, earned a place in baseball history, if not on the list of its immortals, by being on the wrong end of two of the game’s most famous home runs. At 21, he finished up his second season in the majors by serving up the final home run of Ted Williams’s career. The following season the young right-hander was the victim of Roger Maris’s 60th home run, the blast that tied Maris with the immortal Babe Ruth. And yet while those episodes may be the events that have made Fisher a permanent historical footnote, his 11-year career was notable for far more than that. Indeed, while success often eluded him, his efforts on often hapless teams and in difficult situations earned him the respect of teammates and baseball professionals alike, while endearing him to fans who appreciated the consistent efforts of Fat Jack, as he was popularly known.

Jack Fisher was born on March 4, 1939, in Frostburg, Maryland. By the time he was high-school age he was in Georgia, and he played at the Academy of Richmond County in Augusta. In 1957, after high school he was signed by the Baltimore Orioles. Fisher made his professional debut that summer with the Knoxville Smokies of the Class A South Atlantic League, where he pitched in 13 games, made three starts and was 0-5. In 1958 the Orioles moved Fisher down a notch, to the Wilson Tobs of the Class B Carolina League. There Fisher showed that he was the kind of workhorse a club could count on. He threw 221 innings while compiling a 14-11 record with an earned-run average of 3.42. At season’s end he was promoted to the Knoxville Smokies of the Class A South Atlantic League, where he appeared in two games and was tagged with a pair of losses.

Fisher made it to the major leagues in 1959, splitting the year between Baltimore and its Triple-A team at Miami in the International League. He began the season with the Orioles and made his major-league debut on April 14, giving up seven hits and four runs (two earned) in a 13-3 blowout by the New York Yankees in Baltimore. Only 20 years old, Fisher appeared in 27 games for the Orioles.. He started seven and compiled a record of 1-6 with an ERA of 3.05 in 88 2/3 innings for the sixth-place Birds, with his only win a shutout. At Miami he started 12 games, winning eight and losing four while lowering his ERA to 3.06 and throwing seven complete games. In 1960 A member of the Kiddie Korps – all five starters were 22 or younger – he compiled a 12-11 record in 40 appearances (20 starts), with three shutouts and an ERA of 3.41. The young hurlers propelled the Orioles to a surprising second-place finish behind the Yankees. For all that success, it was Fisher’s final start of the season, on September 28 against the Boston Red Sox in Fenway Park, that earned him a permanent spot in baseball annals, for the 21-year old right-hander served up an eighth-inning home run to 42-year-old Ted Williams in the final at-bat of the Splendid Splinter’s illustrious career. It was an at-bat immortalized in John Updike’s famous essay Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu, and later Fisher recalled that while the Fenway faithful screamed for Williams to take a curtain call, looking into the Red Sox dugout he saw baseball’s last .400 hitter telling him to start pitching again – and he did.

With the solid full year under his belt, Fisher again won a regular spot in the Orioles’ rotation in 1961, this time winning 10 games while losing 13 as his earned-run average rose to 3.90. While the Orioles finished third behind the powerful Yankees team, which set a major-league record for home runs, Fisher’s last start again earned him a place as a footnote in baseball history when he became the victim of Roger Maris’s 60th home run, a third-inning blast that tied Babe Ruth’s record for the most home runs in a season. The 1962 season, Fisher’s fourth with the Orioles, saw the stout right-hander struggle. In 25 starts and seven relief appearances he threw only 152 innings, down from 192 of the year before, and he finished with a 7-9 record as his ERA ballooned to 5.09. The Orioles slipped to seventh place in the expanded ten-team league. In the offseason, the Orioles traded Fisher to the National League champion San Francisco Giants in a six-layer deal, and he was hopeful that a change of scenery, if not leagues, would bring a change in fortunes. Unhappily, he also struggled with the Giants, never fully adapted to a role that included significantly more bullpen work (36 games, only 12 starts). He finished with a 6-10 record and an ERA of 4.58, and the Giants slipped to third. The 1964 season brought another change of locale as Fisher was selected by the New York Mets from the Giants in a special draft held in October 1963 to benefit the Mets and the Houston Colts.

Fisher became a centerpiece of the Mets’ staff at the height of the team’s ineptitude, He hurled at least 220 innings in each of the next four seasons, but with limited run support he twice ended up leading the National League in losses. In 1964 Fisher played a prominent role as the Mets opened their new Shea Stadium. In addition to throwing the first pitch – a strike – Fisher also yielded the first hit – and home run, a towering second-inning blast by the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Willie Stargell. But before that Fisher had inaugurated another Shea tradition when, overwhelmed by the noise of the Opening Day crowd, he asked Mets manager Casey Stengel if he could warm up in the bullpen instead of on the field. By the end of the season, Fisher had compiled a mark of 10-17 with an ERA of 4.23 in 227 2/3 innings. The following year he lowered his ERA to 3.94 and was the workhorse of the staff, pitching 253 2/3 innings, while starting 36 games and relieving in seven. He was saddled with the loss in 24 games, winning only eight, as the Mets (50-112) again finished last in the National League, 47 games behind the pennant-winning Dodgers. The 1966 campaign was better as Fisher won 11 while losing 14. He lowered his ERA to 3.68 while starting 33 games and, as he had in 1965, threw 10 complete games. In 1967 Fisher again led the league in losses, this time with 18. He won just nine as he gave up 251 hits in 220 innings. His ERA soared to 4.70 and for the third time in his four years with the Mets, he led the National League in earned runs yielded. Another change of scenery seemed in order and on December 15, 1967, Fisher was traded along with Tommy Davis, Dick Booker, and Billy Wynne to the Chicago White Sox for Tommie Agee and Al Weis, both of whom played major roles in the Mets’ improbable 1969 World Series victory. Back in the American League, Fisher went 8-13 for the 1968 White Sox. He started 28 games and pitched 180 2/3 innings with an impressive ERA of 2.99. He was traded to the Cincinnati Reds and, in his final major-league season, he was 4-4 with an ERA of 5.50 with 15 starts as the Reds finished in third place in the National League West Division. Fisher was traded over the winter to the California Angels but was released before the start of the season, and at the age of 31 he ended his playing career.

In 11 major-league seasons Fisher won 86 games while losing 139. He pitched 1,975 2/3 innings in 400 games with an ERA of 4.06. Although he had only one winning season, he had played for consistently weak teams and was a workhorse for all of them. In that way, Fisher was somewhat typical of his era. Always a competitor – his biggest memory and disappointment at giving up Ted Williams’s final home run was that while Williams’s blast narrowed the Orioles’ lead to 4-3, the Red Sox scored another two runs in the bottom of the ninth to escape with the victory – he pitched deep into games and piled up large numbers of innings pitched, even if the victories were hard to come by.

After retiring as a player in the spring of 1970, Fisher spent a short time as a pitching coach. However, he soon turned his energies to the business world, working for a publishing company for a time before opening his own business. Settling in Easton, Pennsylvania, the home of Lafayette College, and drawing upon the nickname Hoyt Wilhelm had given the stocky right-hander years before, he opened a restaurant, Fat Jack’s, that proved to be an Easton favorite for many years before he sold it in 2006 and embarked on a full-scale retirement.

Sources

Bjarkman, Peter C. The New York Mets Encyclopedia, 2nd edition. Champaign, Illinois: Sports

Publishing LLC, 2003.

Gesker, Mike. The Orioles Encyclopedia. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, editors. Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, second edition. Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc. 1997.

Madden, Michael. “Fisher Relives Final Homer by Ted Williams.” Baseball Digest, November 1987.

Seidel, Jeff. Baltimore Orioles: Where Have You Gone? Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2006.

Smith, Ron. 61*. St. Louis: Sporting News. 2001.

Updike, John. Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu. New York: The Library of America, 2010.

www.centerfieldmaz.com

Full Name

John Howard Fisher

Born

March 4, 1939 at Frostburg, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.