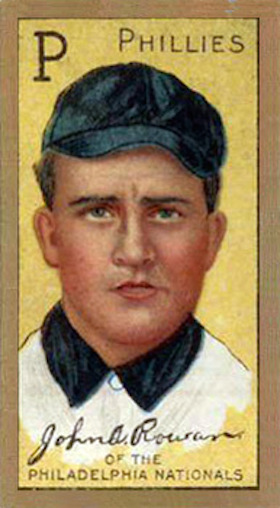

Jack Rowan

In late July 1958 newspapers nationwide published a brief Associated Press dispatch announcing the death of Deadball Era pitcher Jack Rowan.1 Follow-up articles supplied poignant detail. The elderly gent, believed to be about 85 and without family, had spent his final years living alone in a small Detroit hotel room, surviving on a small monthly stipend provided by the Association of Professional Base Ball Players of America. That dole had been secured for him through the intervention of a prominent local clergyman, Auxiliary Bishop John A. Donovan of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Detroit. For years prior to his death, Rowan had divided his time between making himself useful at a downtown Catholic church and taking in Tigers games at Briggs Stadium, where he regaled fellow onlookers with tales of his bygone hurling exploits.2

In late July 1958 newspapers nationwide published a brief Associated Press dispatch announcing the death of Deadball Era pitcher Jack Rowan.1 Follow-up articles supplied poignant detail. The elderly gent, believed to be about 85 and without family, had spent his final years living alone in a small Detroit hotel room, surviving on a small monthly stipend provided by the Association of Professional Base Ball Players of America. That dole had been secured for him through the intervention of a prominent local clergyman, Auxiliary Bishop John A. Donovan of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Detroit. For years prior to his death, Rowan had divided his time between making himself useful at a downtown Catholic church and taking in Tigers games at Briggs Stadium, where he regaled fellow onlookers with tales of his bygone hurling exploits.2

All of this was read with some degree of astonishment by a retired postal worker living in Dayton, Ohio: the actual Jack Rowan. “There must be some mistake,” he told inquiring reporters.3 This Rowan, also without family, did not begrudge some impostor eking out an existence through impersonating him. But he was concerned that the deceased might be interred in the family cemetery plot reserved for him back in Rowan’s hometown, New Castle, Pennsylvania.4 As it turned out, the faux Jack Rowan was buried in Detroit, his true identity undiscovered. When the real Rowan died in 1966, his passing created none of the stir of eight years earlier. In fact, the death of the real Jack Rowan went unnoted in the press.5

The genuine article was born John Albert Rowan on June 16, 1886. At the time of his birth, New Castle was a bustling manufacturing and railroad hub located about 50 miles northwest of Pittsburgh and not far from the border of Ohio. Jack was the youngest of the five children6 born to John Rowan (1843-1910) and his wife, Lydia (née Lakey, 1847-1916). The elder Rowans were immigrants. John was a Scotch-Irishman born in what is now Northern Ireland, while Lydia was a native of Wales. The two met, married, and began raising a family in eastern Ohio. In time the Rowans relocated to New Castle, where John found work as a blast-furnace engineer, and the family became active members of the First Christian Church.7 Young Jack was educated locally through graduation from New Castle High School,8 where he was a standout center on the school football team.9 He then started his working life as an apprentice boilermaker.

Rowan began pitching for semipro teams in and around New Castle while still in high school, getting an early taste of the hard luck that would often dog him during his professional career. In one outing he struck out 22 enemy batsmen, yet still lost, 7-2.10 In another local contest, Rowan broke a thumb.11 He entered the pro ranks in 1906, signing with the Leavenworth (Kansas) Old Soldiers of the Class C Western Association. Physically imposing at 6-feet-1 and 212 pounds and possessed of a blazing fastball but erratic control, right-hander Rowan quickly evoked images of a young Amos Rusie, minus the surly Rusie disposition and unslakable thirst. Sobriety, diligent work habits, and a sunny, upbeat personality would make Jack Rowan a favorite of teammates, fans, and the sporting press wherever he went.

In the 35 games of his maiden pro campaign, the 20-year-old Rowan pitched well, posting an 18-10 (.643) record for a lackluster sixth-place Leavenworth club that otherwise went 50-62 (.446). Such good work did not go unnoticed by major-league clubs and that September, Rowan was selected in the minor-league player draft by the Detroit Tigers.12 Jack was joining a talented but troubled team, with many Tigers players in near-open revolt against manager Bill Armour. By the time Rowan donned Detroit livery, feigned illnesses, phantom injuries, truancy, and the like frequently left Armour short of players and/or necessitated the playing of those men available out of position.13 And it was another such act of insubordination that spawned the major-league debut of Jack Rowan. On September 6 discontented staff ace George Mullin went AWOL, failing to appear at Navin Field for a scheduled start against the pennant-bound Chicago White Sox. Thrust into the breach on short notice, Rowan endured a nightmarish first inning, surrendering eight runs. Thereafter, he “pitched a fairly good game … and was deserving of better treatment” than what he received from loud and scornful Tigers fans.14 Rowan labored manfully to the finish, surrendering 15 base hits and six walks while striking out none in a 13-5 drubbing. He did not get a second pitching opportunity with Detroit that season.

Despite his unimpressive audition, Detroit remained interested in Rowan. He was reserved by the Tigers for the 1907 season15 and accompanied the club south for spring training.16 Rowan performed inconsistently in camp but apparently made the Tigers’ Opening Day roster.17 But he saw no game action before Detroit optioned him to the Atlanta Crackers of the Class A Southern Association, thus initiating a dizzying personal odyssey that is difficult to reconstruct with surety. But it appears that Atlanta was overstocked with pitching and had no available spot for Rowan.18 So, the Crackers promptly dispatched him to the Augusta Tourists of the Class C South Atlantic League.19 No record could be found, however, of Rowan actually pitching for Augusta. Rather, he appears to have remained with Atlanta, where he posted a 2-4 mark in eight appearances. Rowan was then released to another SALLY League team, the Macon Brigands.20 The Charleston Evening Post appraised the situation thusly: “Jack Rowan, the Michigan giant, who was farmed out by Detroit to Atlanta and by Atlanta to Macon … has everything but control. For speed he is a wonder, and if he could throw strikes, no one could touch him. … He is a genial, clever youngster and is popular everywhere he works.”21 After going 6-4 for Macon, Rowan was recalled by Detroit,22 but only for the purpose of selling his contract to the Dayton Veterans of the Class B Central League.23 That transaction permanently severed Rowan’s connection to Detroit.

Rowan blossomed at once in Dayton. Early in the 1908 season, he registered a skein of 26 consecutive scoreless innings,24 and soon attracted the interest of major-league clubs once again. In mid-July the Cincinnati Reds purchased Rowan, with delivery set for the end of the Central League season.25 Shortly after he had pitched and won both ends of an August 8 doubleheader, the Reds put out the call for Rowan to report. But Dayton, thick in the Central League pennant chase, refused to relinquish him prematurely.26 Rowan finished the campaign at 23-14, with an excellent 2.16 ERA in 333 innings pitched for Dayton. Big Jack was also the circuit strikeout king (232).

Once arrived in Cincinnati, Rowan got an immediate taste of the weak offensive support that would plague his time pitching for the Reds. On September 6, 1908, he dropped a well-pitched 3-1 decision to the St. Louis Cardinals. Two days later, Jack was a 3-2 loser to the Chicago Cubs. In these two outings, the Reds had backed him with six hits, total. Still, the Cincinnati Post was favorably impressed, informing readers that the newcomer “fields his position splendidly, is cool, has the speed of Rusie, and the strength of a Goliath.”27 Rowan registered his first major-league victory the following week, a 3-2 triumph over Pittsburgh. He continued to pitch well during the closing weeks of the season, throwing a six-hit, 1-0 shutout at the Philadelphia Phillies. He finished with a 3-3 record, highlighted by a sparkling 1.82 ERA in 49⅓ innings pitched for the Reds.

Based on his late-season showing, big things were expected of Big Jack in 1909. But his progress was retarded when he showed up overweight in spring camp. A fondness for strawberry shortcake was deemed the culprit.28 Rowan was also handicapped by a limited pitching repertoire. He was largely a one-pitch (fastball) pitcher. To remedy that, new Reds manager Clark Griffith, the possessor of 237 major-league victories, attempted to teach Rowan how to throw a slow ball.29 In the early-season going, Jack pitched sparingly but well, getting off to a 4-0 start. But control problems remained a handicap. By early July, Cincinnati sportswriter Ren Mulford Jr. tartly observed: “Now they call Jack Rowan an Amos Rusie in embryo. What Jack has to do, and do quickly, is find out where home plate is located.”30 Unhappily for Rowan and the Reds, he never quite mastered the art, walking 104 (as compared to 81 strikeouts) in 225⅔ innings pitched. But a fine 2.79 ERA and .233 OBA reflected the ample quality of Rowan’s stuff. In the end, his uneven 11-12 final record was about on par with the 77-76 mark posted by the fourth-place Cincinnati club he pitched for, but was a disappointment nonetheless.

The 1910 season was a near-repeat for both Rowan and the Cincinnati Reds. As in the previous year, preseason expectations ran high for the still-young pitcher. Under the headline “Much Is Expected of Jack Rowan This Year,” the Cincinnati Post extolled the expansion in Rowan’s pitching arsenal, which now included “a better curve, a corking slow ball, and a deceptive drop” in addition to his devastating fastball.31 Rowan was equally optimistic about the coming season. As Opening Day approached, he pronounced himself in excellent physical condition and said, “[M]y arm feels 80 per cent stronger than it did at this time last year.” Given that, Jack declared, “I will be greatly disappointed if I am not able to rank with the team’s winningest pitchers.”32 But control problems persisted, and by late May, the Post had soured on him, observing, “Jack Rowan looks good occasionally, but is as wild as a cat with a hairpin stuck through its tail.”33 He then straightened out, with a two-hit, 2-0 victory over the Boston Rustlers (or Braves) on July 13, extending a Rowan scoreless string to 21 consecutive innings pitched.34 By season’s end, the Rowan stat line – 14-13, with a 2.93 ERA/.254 OBA and 105 walks compared with 108 strikeouts – was arguably a marginal improvement over his 1909 numbers, while the Reds fifth-place (75-79) finish was a baby step backward from the previous year.

The offseason proved a momentous one for Rowan. In October he was part of an eight-player swap between the Reds and the Philadelphia Phillies, and then was left in limbo when Phillies club owner Horace Fogel disputed the authority of his manager, Red Dooin, to make the deal.35 A threat to haul Fogel before the National Commission made by Reds boss Garry Herrmann, however, hastened a quick change of his position on the matter, and the trade was thereafter ratified on all sides.36 Rowan was now officially a member of the Philadelphia Phillies. Only weeks later, Rowan was injured in a tandem motorcycle accident which left his right arm badly injured, but not broken.”37 Still, the mishap, however serious, could not keep Rowan from the altar. On December 22, 1910, he married 22-year-old Fern Allen of Dayton. (But sadly, the union would prove childless, and the couple would eventually divorce in the early 1930s.)

When he showed no effects of his offseason injury during spring training, expectations in Philadelphia rose as high for Rowan as they had been in Cincinnati. But the best major-league days of the not-yet-25-year-old were already behind him. Nevertheless, the season began on a personal high note. After repeated attempts, Jack finally posted a victory over pitching icon Christy Mathewson, beating him and the Giants 6-1 on April 14. A delighted manager Dooin predicted great things for his new hurler. “I pick [Rowan] to be one of the star pitchers of the National League season,” said Red.38 Reality would prove different. In fact, Rowan won only one more game for Philadelphia, another complete-game triumph over the Giants a week later. Thereafter, he was near-useless. After several ineffectual outings, Ren Mulford diagnosed Rowan’s problem as too much time spent in the club commissary. “A crowded stomach is not good for athletic prowess,” the sportswriter remarked.39 By late June, the Phillies had removed Rowan from the starting rotation and gotten him through waivers. All that was now required was location of a suitable place for unloading him.40 Meanwhile, Rowan, banished to the sidelines, tinkered with a spitball while awaiting his traveling orders.41

On August 11 the Phillies and Cubs exchanged large, underperforming right-handers, the Phils getting Cliff Curtis (6-feet-2/180 pounds, with a 2-10 record in combined stints with Boston and Chicago) in exchange for Rowan (2-4, and having allowed some 80 baserunners in 45⅔ innings pitched). Chicago manager Frank Chance was a Rowan admirer, but one woeful relief effort – four runs surrendered in two innings – was all the action he would afford his new acquisition. As the 1911 season came to a close, Rowan was dispatched to the minors, his contract sold to the Louisville Colonels of the American Association.42

Rowan’s time in a Louisville uniform was brief and unproductive. In seven early-1912 games, he went 0-4 for the Colonels.43 Rowan was then sold to the Denver Grizzlies of the Class A Western League,44 a minor-league circuit a notch lower than the American Association. By this time Rowan had grown accustomed to a major-league wage and refused to report for what Denver was offering him.45 Returned to Louisville, Big Jack was placed on Organized Baseball’s suspended list, while club management looked for another berth for the recalcitrant hurler. In time, a congenial placement was found for Rowan: the Dayton Veterans of the Central League. Although a member of a minor-league circuit in a yet-lower classification (Class B), Dayton had become Rowan’s permanent place of residence, and he promptly joined his new club.46

Perhaps unexpectedly, the trip to Dayton rejuvenated Jack Rowan’s career. While there, veteran minor-league pitcher Ed Schulze showed him a new and more effective grip for his curveball. The result was a sharp-breaking bender to complement the still-impressive Rowan fastball.47 Jack finished the season going 9-6 for the Veterans, and had reached the 17-victory mark for Dayton the following season when the Cincinnati Reds reclaimed him.48 Rowan may have returned to Cincinnati equipped with better stuff, but his luck had not changed much. The Reds still would not hit for him. On September 13 Jack’s first engagement ended in a 1-0 loss to Boston. Two days later, 10 innings of excellent work yielded no more than a 2-2 tie against Philadelphia. Thereafter, a two-run ninth-inning rally by Brooklyn cost Rowan another loss, 2-1. In all, Jack went 0-4, with Reds teammates supporting him with a grand total of seven runs in his five starts.

The winless results of late 1913 notwithstanding, Rowan once again figured in Cincinnati pitching plans.49 But a spring bout of tonsillitis set him back,50 and he was hit hard upon being cleared for duty. Soon, Rowan was consigned to mop-up relief chores. A typical appearance occurred during the first game of a June 28 doubleheader against Pittsburgh. With the Pirates ahead 6-2 after eight innings, Jack was sent out to pitch the top of the ninth. Five pitches thrown produced three groundball outs and returned him safely to the bench to witness the game’s conclusion. Once there, he became the beneficiary of the improbable five-run rally staged by his teammates, and thus was credited with the 7-6 Cincinnati victory.51 It was his last major-league win. Two weeks later Rowan was sold to the Chattanooga Lookouts of the Southern Association,52 bringing his big-league days to their end.

For the most part, Rowan’s career had been one of unfulfilled promise. In 119 games, he had gone a substandard 31-40 (.437), but with a Deadball Era-decent 3.07 ERA in 670⅔ innings pitched. In those frames, he had allowed 623 base hits (yielding a .255 OBA), striking out 267 enemy batsmen while walking 272. Control problems and a limited pitching repertoire had been his principal shortcomings, but they were somewhat offset by the durability, strong work ethic, and amiable disposition that had made Big Jack a favorite of most connected to the game. In short, he had been a good guy but, at best, a mediocre major-league pitcher.

Rowan’s easygoing nature was not to be confused with a weak will, and once again he refused to play in a minor-league venue that was not agreeable to him. He had not enjoyed his previous experience pitching in Southern summer heat and had no intention of doing it again. So he refused to report to Chattanooga.53 But a return to the Dayton Veterans suited Rowan fine. He finished his professional career with a small flourish, leading Central League hurlers in winning percentage (.800) in 1916, and wound up a three-year stint in Dayton with a 38-37 record, overall. His time there, however, ended on an abrupt and tragic note. Late in the 1917 season, the train carrying the Dayton club collided with a fast-moving freight near Champaign, Illinois. With the miraculous exception of an unscathed Jack Rowan, every Dayton player was injured, some seriously. Former major leaguer Rube Kroh suffered a severed artery in his arm and was scalded by steam, while outfielder Ray Spencer received head injuries that ultimately proved fatal.54 Several other Dayton players were maimed, and with the club roster decimated, the Central League completed the last two weeks of its season without the Dayton Veterans.

As an almost 32-year-old married man, Rowan was not a likely candidate for World War I military conscription as the next season began. But the Central League, like many other minor league circuits, remained dormant in 1918, leaving Jack to pitch for local semipro nines like the Dayton Rubbers.55 The following year, Jack abandoned the game altogether to take a position with the US Post Office in Dayton, a job that he would hold for the remainder of his working life. Following retirement in 1950, Rowan, by now divorced, childless, and bereft of immediate family,56 lived quietly in Dayton. The death of the bogus Jack Rowan dragged him from the anonymity of private life briefly in 1958, but not for long. In his final years, Rowan, suffering from arteriosclerosis, resided in a Dayton nursing home. He died there on September 29, 1966, from the effects of a stroke.57 John Albert “Jack” Rowan was 80. His interment was at Dayton Memorial Park.

Sources

Sources for the biographical information contained herein include the Jack Rowan file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York: US Census data; Rowan family-related info posted on Ancestry.com, and certain of the newspaper articles cited below. Unless otherwise noted, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference and/or The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 2nd ed., 1997).

Notes

1 See, e.g., the Washington (DC) Evening Star, July 29, 1958, and the Boston Record and Sacramento Bee, July 30, 1958.

2 See the Baton Rouge Advocate, Dallas Morning News, and Omaha World-Herald, July 31, 1958.

3 Ibid. See also, the St. Petersburg (Florida) Times and The Sporting News, August 6, 1958.

4 For more recent considerations of the controversy, see “Who Is the Real Jack Rowan?” accessible via baseballhistorydaily.com/2012/09/10, and Betty Hoover DiRisio, “Will the Real Jack Rowan Please Stand Up?” The (Lawrence County, Pennsylvania) Little Local Paper, January 21, 2015.

5 A search of newspaper archives maintained by ProQuest, GenealogyBank, and Ancestry failed to uncover a 1966 obituary or death notice for Jack Rowan.

6 Jack’s older siblings were William (born 1873), Lydia (1877), Maud (1880), and Jennie (1883).

7 In the writer’s view, the fact that the Rowans were not Catholic is a small but telling circumstance that confirms that the beneficiary of Bishop Donovan’s intervention was an impostor, and not the real Jack Rowan.

8 As per the late-life questionnaire submitted to the Hall of Fame library by Rowan himself.

9 As per the Cincinnati Post, March 26, 1909.

10 According to the Cincinnati Post, March 18, 1914.

11 As reported in the New Castle (Pennsylvania) News, May 31, 1905.

12 As reported in the Evansville (Indiana) Courier, September 4, 1906, Washington Evening Star, September 5, 1906, and Sporting Life, September 8, 1906.

13 As reported in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 7, 1906.

14 In the estimation of the Chicago Tribune, September 7, 1906.

15 As noted in Sporting Life, October 20, 1906.

16 As per Sporting Life, February 16, 1907, and the Adrian (Michigan) Messenger, February 24, 1907.

17 According to Detroit sportswriter Paul H. Bruske in Sporting Life, April 13, 1907.

18 According to the Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, May 2, 1907.

19 As reported in the Augusta Chronicle, May 2 and 4, 1907, and Sporting Life, May 25, 1907.

20 As reported in the Atlanta Georgian, June 26, 1907, and the Charleston Evening Post, June 28, 1907.

21 Charleston Evening Post, July 30, 1907.

22 As reported in the Boston Herald, July 11, 1907, Evansville Courier, July 18, 1907, and Sporting Life, July 20, 1907.

23 As reported in the Macon (Georgia) Telegraph, August 31, 1907. See also, the Evansville Courier, December 6, 1907.

24 According to the Evansville Courier, May 6, 1908.

25 As per the Cincinnati Post, July 10, 1908, and Muskegon (Michigan) Chronicle, July 19, 1908.

26 As reported in the Evansville Courier, August 20, 1908. Dayton also refused to release outfielder Bob Bescher, another midseason Cincinnati purchase not yet due for delivery.

27 Cincinnati Post, September 8, 1908.

28 See the Cincinnati Post, March 1, 1909.

29 As reported in the Cincinnati Post, April 7, 1909.

30 Sporting Life, July 3, 1909.

31 Cincinnati Post, March 28, 1910.

32 Ibid.

33 Cincinnati Post, May 28, 1910.

34 As noted by “Ros” in his July 14, 1910, column in the Cincinnati Post.

35 As reported in the Cincinnati Post and Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times-Leader, October 26, 1910, and elsewhere.

36 See the Jersey Journal (Jersey City), November 14, 1910. In addition to Rowan, the Phillies acquired pitcher Fred Beebe, third baseman Hans Lobert, and outfielder Dode Paskert, while Cincinnati received pitchers Lew Moren and George McQuillan, third baseman Eddie Grant, and outfielder Johnny Bates.

37 As reported in the (Springfield) Illinois State Journal, December 3, 1910, Pawtucket (Rhode Island) Times, December 5, 1910, Salt Lake Telegram, December 7, 1910, and elsewhere.

38 As per the Cincinnati Post, April 14, 1911.

39 Sporting Life, May 27, 1911.

40 As per the Cincinnati Post, July 11, 1911, and Sporting Life, July 22, 1911.

41 As per Sporting Life, August 5, 1911.

42 As reported in the New Orleans Item, October 5, 1911.

43 Baseball-Reference does not include his stay with Louisville in Rowan’s statistics. The record supplied above was calculated by the writer from Louisville box scores for games played from May 5 to June 4, 1912.

44 As reported in the Evansville Courier, June 4, 1912, Denver Post, June 6, 1912, and elsewhere.

45 Denver Daily News, June 17, 1912.

46 See Sporting Life, July 6, 1912.

47 As per the Cincinnati Post, August 24, 1912.

48 Dayton’s sale of Rowan to Cincinnati was noted in the Canton (Ohio) Repository and Kansas City Star, August 20, 1913, and Sporting Life, August 30, 1913.

49 See “Jack Rowan One Big Hope for Red Staff,” Cincinnati Post, February 7, 1914.

50 As reported in Sporting Life, May 2, 1914.

51 As reported in the Cincinnati Post, June 29, 1914.

52 As reported in the Pawtucket Times, July 13, 1914, Grand Forks (North Dakota) Herald, July 15, 1914, and elsewhere.

53 As per the Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, July 14, 1914, and Sporting Life, July 18, 1914.

54 The train wreck was widely reported. See, e.g., the Baltimore Sun, Pawtucket Times, and Philadelphia Inquirer, August 25, 1917. Word of Spencer’s subsequent death was published in the Boston Journal, Cincinnati Post, and Evansville Courier, September 15, 1917.

55 As noted in the Cincinnati Post, June 22, 1918.

56 His parents were long deceased, and the death of older sister Lydia Rowan Moore (reported in the New Castle News, March 27, 1943) had made Jack the last surviving Rowan sibling.

57 The death certificate contained in Rowan’s file at the Giamatti Research Center posits the official cause of death as CVA (cerebral vascular accident).

Full Name

John Albert Rowan

Born

June 16, 1886 at New Castle, PA (USA)

Died

September 29, 1966 at Dayton, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.