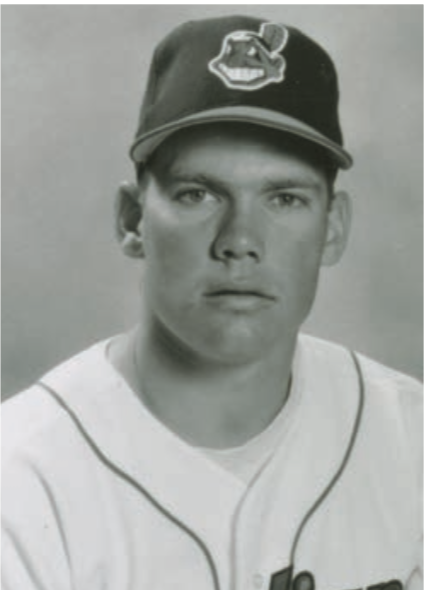

Jason Grimsley

To experience the heart-pounding thrill of espionage, the horror of a plane falling from the sky, or the dread of government agents laying siege to your home, would by itself be enough for any person’s lifetime, let alone enduring all three – not to mention, all while engaged in the rigors of a major-league baseball career. Yet that’s what happened to Jason Alan Grimsley. Oh, and we shouldn’t overlook the World Series rings that he won.

To experience the heart-pounding thrill of espionage, the horror of a plane falling from the sky, or the dread of government agents laying siege to your home, would by itself be enough for any person’s lifetime, let alone enduring all three – not to mention, all while engaged in the rigors of a major-league baseball career. Yet that’s what happened to Jason Alan Grimsley. Oh, and we shouldn’t overlook the World Series rings that he won.

That’s quite a scrapbook for an “aw-shucks” kid from Cleveland, Texas, near Houston. Born on August 7, 1967, by all accounts Grimsley grew up, along with his brother, Joe, in a close-knit family nurtured by their parents, Johnny, a pipeline welder, and Judy. Living out in the country, the Grimsley boys undoubtedly were free to roam and play. One anecdote evokes visions of the kind of childhood they must have led, but also depicts the natural athleticism young Jason assuredly possessed. When he turned 12 years old, his parents gave him and his brother dirt bikes to ride over acres of land, owned by Mrs. Grimsley’s family, that adjoined the Grimsleys’ homestead. One day, while riding through his aunt’s backyard, Jason caught his big toe on a tree stump. Although the toe was eventually amputated, several months later Grimsley earned a spot on his eighth-grade basketball team, and later that spring took second in the high jump at a regional competition. (Years later, after he battled throughout his professional career to conquer control problems on the mound, it would be written of Grimsley that “executives have speculated for years that his control might have been greatly improved if he had more stability on the foot he lands on in his delivery.”1)

Moving to the next scholastic athletic level, Grimsley proved even better; at Cleveland’s Tarkington High School, he became a star. Besides leading the school football team as the starting quarterback, Grimsley displayed a nasty slider on the pitching mound. That drew the attention of the Philadelphia Phillies, who selected the 6-foot-3, 180-pound right-hander in the 10th round of the 1985 amateur draft.

Grimsley was as raw as a prospect could be. Beginning with the Phillies’ short-season Class A Northwest League affiliate in Bend, Oregon, the 17-year-old spent the next four seasons in Utica, New York; Spartanburg, South Carolina; Clearwater, Florida; and Reading, Pennsylvania, trying to harness his often-stunning bouts of wildness and learning how to pitch. It rarely came easy, as evidenced from his body of work during that period. From his first minor-league pitch in 1985 until the evening of his major-league debut in September 1989, Grimsley pitched in 90 minor-league games (69 starts) and threw 459 innings. Over that span he averaged 6.2 walks per nine innings (down from 19.9 and 10.7 in his first 20 games), as well as 6.3 hit batsmen and 9.6 wild pitches per season (11 and 18, respectively, in his first full season). Over that same span, though, he allowed just under seven hits per nine innings and struck out almost eight, clearly a sign of his overwhelming potential.

By September 5, 1989, Grimsley finally appeared to have, if not cured, at least minimized his wildness, winning 11 games with a 2.98 ERA in 26 starts for the Double-A Reading Phillies (Eastern League); over his last five starts, his ERA had been a minuscule 1.47.2 That day, despite having never yet pitched at Triple A, Grimsley was called to Philadelphia, where he joined the last-place Phillies in the middle of a homestand vs. the Pittsburgh Pirates.

“I thought he’d be all right to bring here [from Double A],” said Phillies general manager Lee Thomas at the time. “He’s confident. He’s not a shy guy. I believe if a guy can pitch at Double A, he can play here.”3

Thus began Grimsley’s often tumultuous, well-traveled 15-year major-league career.

Three days after his recall, the Phillies were in Montreal to play the Expos. With Grimsley’s arrival, Phillies left-handed starter Dennis Cook had been moved to the bullpen, so that night Grimsley went to the mound as a starter in his major-league debut. Through 3½ innings the teams were scoreless. In the bottom of the fourth, the Expos nailed Grimsley for a triple and single to take a 1-0 lead. In the top of the fifth, however, the Phillies scored three times. In the top of the sixth, Grimsley was pulled for a pinch-hitter, and when Philadelphia held on for a 4-3 win, he was the winning pitcher, the first of his 42 career victories. Over the remaining three weeks of the season, Grimsley made three additional starts but struggled mightily with his control, allowing 19 walks in just 18⅓ innings. He lost each of those games.

It had been an inauspicious start for the 21-year-old, but he was solidly on the Phillies radar … for a time, at least. Grimsley opened the next season, 1990, with the Triple-A Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Red Barons. As the Phillies, showing improved play on their way to an eventual 10-win increase and fourth-place finish in the National League East, hung around the .500 mark for the first half of the season, Grimsley won eight games as a starter for Scranton and limited his walks to just over five per nine innings. Then the Phillies began to lose steam. Once again, they recalled Grimsley to Philadelphia. This time he fared much better.

Arguably, the 11 starts Grimsley made for the Phillies over the final three months of the 1990 season, during which he won three and posted a 3.30 ERA, proved the pinnacle of his career as a starter. For in the following year, after opening the season in the Phillies rotation, he endured an abysmal 1-7 record in 12 starts, and in August, following a stint on the disabled list and a rehab assignment, was optioned back to Scranton/Wilkes-Barre. It proved to be the end of his Phillies career.

(In 1999, then with the Yankees, and at the height of his career, Grimsley told a sportswriter for the New York Daily News about the years he had spent bouncing around the minor leagues: “Hey, I’ve gotten to play baseball for a living. I wouldn’t have met my wife (Dana) without it, because we met when I was in spring training with the Phillies in 1991 at a Chamber of Commerce event I was obligated to go to by the club.”4 Eventually, the Grimsleys produced three children: sons Hunter and John-John, and daughter Rayne.

If Grimsley proved a frustrating prospect for Philadelphia, so too did another right-hander, Curt Schilling, prove equally frustrating for the Houston Astros. As Schilling entered the Astros’ 1992 spring training “overweight, under-inspired and out of options,”5 Grimsley, too, was out of options, meaning the Phillies had to either keep him on their 25-man roster or risk losing him to waivers. As the end of spring training neared, it was rumored that the Phillies were trying to acquire outfielder Ruben Sierra from the Texas Rangers in a trade that would include Grimsley.6 Whether or not that rumor was true became moot on April 2, however, when the Phillies and Astros consummated a trade of their disappointing right-handers. It was a deal that proved overwhelmingly one-sided. As Schilling blossomed, going 14-11 with a 2.35 ERA and solidified himself in the Phillies rotation, Grimsley spent the entire 1992 season at Triple-A Tucson, where he produced a hefty 5.05 ERA.

Grimsley’s season was a tale of two halves. During the first half he was terrible, posting a record of 1-5 with an astronomical ERA. Over the second half, though, he finished a promising 7-2 and ended the season with 55 walks in 124⅔ innings pitched. Looking to build on that second-half success, Grimsley went after the season to Venezuela, where he pitched for Magallanes. He threw well, walking only seven batters in 30⅔ innings. There, one night, Florida Marlins scouting director Gary Hughes watched Grimsley pitch.

“The only thing that gets him in trouble,” said Hughes, “is terrible control. He has real good stuff. If he’s around the plate he can beat anybody, but there always seems to come a time when – boom – he loses it.”7 That night Grimsley had gone eight innings and allowed just one run, but walked five.

Later, Grimsley told the press, “Everything is upbeat. It looks like things are turning around. (Astros officials) said in the newspaper the way I threw in Venezuela, I’d put my hat in the ring for the fifth starter’s spot.” About his improvement in the second half of the season, Grimsley said, “I was throwing across my body. Now I have found a consistent release. All I’ve got to do is get consistent, throw strikes. My ball has always moved. Now I have an idea how to use that to advantage.”8 That optimism, though, proved illusory.

On March 30, 1993, Grimsley was released by the Astros. He wasn’t unemployed for long. Tragically, on March 22 Cleveland Indians pitchers Steve Olin and Tim Crews had been killed in a spring-training boating accident in Florida. With starting pitcher Bob Ojeda injured in the accident, too, the Indians were desperate for pitching. On April 7 Cleveland signed Grimsley as a free agent and sent him to their Triple-A affiliate at Charlotte. Grimsley quickly set about trying to resurrect his career.

Managed by Charlie Manuel, who would later win a World Series with the Phillies, the 1993 Charlotte Knights, who finished 83-58, featured some of the players who would shortly arrive in Cleveland and take the Indians to multiple World Series, Manny Ramirez, Jim Thome, et al. Put in the starting rotation, he pitched well through mid-August, posting a 3.39 ERA and limiting his walks to 3.2 per nine innings. Then he got a call to join the Indians. On August 25 in Toronto, Grimsley made his first major-league relief appearance, surrendering three hits and two runs in 2⅓ innings. After three more relief stints, Grimsley started on September 2 at Minnesota and allowed two runs in six innings, walking five. After that game, a no-decision of Grimsley, Indians manager Mike Hargrove assessed, “I thought Jason threw very well. The only thing that bothered me is that he pitched behind in the count too much. I thought he threw enough strikes so that I didn’t have to cross my fingers. I liked what I saw. He has good stuff. His ball moves all over the place.”9 Hargrove gave Grimsley five more starts before the season was ended, during which Grimsley allowed four earned runs in 19 innings over the last three games, and things looked promising for him to contend for a rotation spot in 1994. But he failed to make the squad in ’94 and was sent to Charlotte.

In June the Indians, struggling to find a reliable fifth starter, recalled Grimsley. As the Indians surged to a 66-47 record and a second-place finish in the American League Central Division, Grimsley won five games and walked 3.7 batters per nine innings in the period before a strike by the players union ended the season. But it was a game in which he didn’t pitch that would later garner for Grimsley the most attention.

Two noteworthy things happened during the 1994 season. One was the players strike; the other was a caper the press dubbed “Batgate.”

In April 1999 Grimsley confessed to the caper, which had stumped the sport for five years. On July 15, 1994, the Indians played the White Sox in Chicago. Before the game someone tipped off White Sox manager Gene Lamont that Indians slugger Albert Belle’s bat was corked. Lamont challenged the use of the bat, and umpire Dave Phillips took the bat and stored it in his locker in the umpire’s room. Panic ensued among the Indians, who knew that the bat was corked. So, Grimsley volunteered to retrieve it.

“It was mission impossible,” Grimsley said.10 … “We were sitting there in a pennant race, and for some reason I got it into my head, ‘Go get the bat.’ I just went over and got it.”11 Assuming that the umpires’ room was on the same side of the ballpark as was the Indians’ clubhouse, Grimsley climbed through the false ceiling of the clubhouse, crawled on his belly with a flashlight in his mouth, found the hatch to the umpires room, and dropped down onto a refrigerator. Once inside, Grimsley took Belle’s bat from the locker and exchanged it with one that bore the signature of teammate Paul Sorrento, the evidence that ultimately led the umpires to suspect foul play. The police were called to the scene and the White Sox threatened to press charges; but in the end the Indians were told that if they supplied Belle’s bat, there would be no punishment for the switch.

Throughout the caper, Grimsley later related, “My heart was going a thousand miles a second.”12 Belle received a 10-game suspension, which was later reduced to seven games. Until Grimsley’s confession five years later, the culprit went unidentified.

That the stolen-bat escapade generated more excitement in baseball circles than Grimsley’s pitching is indicative of his fortunes over the next four years. He labored to remain a viable major-league pitcher. As the Indians broke a 41-year drought and went to the World Series in 1995, Grimsley pitched in just 15 games for the Tribe, only two as a starter; he ended the season at Triple-A Buffalo. Then, on February 15, 1996, Cleveland shipped Grimsley and right-hander Pep Harris to the California Angels for left-hander Brian Anderson. Although Grimsley started 20 games that season for the Angels, his ERA was 6.84. In October he was released.

Over the next two seasons, Grimsley reached his nadir. Beginning in January 1997, when he signed a minor-league deal with the Detroit Tigers, he bounced among three organizations (Milwaukee, Kansas City, and Cleveland, again), without returning to the major leagues. By the end of 1998, after 52 relief appearances for Buffalo, the Indians’ Triple-A affiliate, Grimsley must have questioned whether his career was over, for that fall, at age 31, he was released by Cleveland. As it turned out, though, his fortunes were soon dramatically changed.

Among pitchers, baseball history is rife with reclamation projects. That’s what Grimsley was in 1999, and that season he turned his career around. As Grimsley performed well at Buffalo in 1998, the Yankees director of player personnel, Billy Connors, a former pitcher, watched him pitch and persuaded the Yankees to sign Grimsley. New York signed him to a minor-league contract with an invitation to spring training. (They also threw in a $10,000 bonus.)13

At spring training in Tampa, Florida, Connors persuaded Grimsley to change his repertoire, which to that point consisted of four pitches: two fastballs, a curve, and a slider; rather than mixing his pitches Grimsley would refine control of one devastating pitch, a sinking fastball. The results were immediate and impressive: Grimsley earned a spot on the Opening Day roster.

Coming out of the bullpen, he started the year strongly. Early in the season, Yankees reliever Jeff Nelson went on the disabled list, so Grimsley got lots of work. He put together a string of strong performances – so strong, in fact, that questions about the nature of those performances soon arose. It was statistically quite a stunning turnaround. Entering the season, Grimsley had compiled a major-league ERA of 5.39, allowing 450 hits in 426 innings pitched. By contrast, through the end of May 1999, he was practically unhittable: In 29⅓ innings pitched he allowed only 17 hits and struck out 25 while walking only 7; with a 4-0 record, his ERA was 2.15.

Accusations arose that Grimsley was doctoring the baseball. On May 9 at Yankee Stadium, Seattle manager Lou Piniella complained to the umpire that Grimsley’s pitches were “sinking and moving too much to be a product of natural forces.”14 On May 26, Boston’s Jose Offerman grabbed the ball after striking out against Grimsley and checked it for cuts. No marks were found.

Whether or not Grimsley was doing something to the ball, sportswriters praised his singular “power sinker.” “What Grimsley is doing could not be more simple,” wrote Buster Olney in the New York Times. “He grips the ball with his right index and middle fingers close together, between the seams, his fingertips resting in the spot where a player might sign an autograph, and he throws as hard as he can. There is no mystery. There is no deception.”15 Yankees catcher Joe Girardi offered, “His sinker is unbelievable. The movement is so hard, and it’s so late.”16

The hitters knew Grimsley’s sinker was coming; he threw it 85 percent of the time. Olney wrote, “They cannot hit it. The sinker is unusual in that it moves vertically, straight down, rather than at a downward 45-degree angle. … The movement … is so violent that scouts sitting behind home plate have asked each other if Grimsley is throwing a split-fingered fastball.”17

For his part, Grimsley took all the accusations in stride, stating, “I take that more or less as a compliment. I hope everybody complains, because that will tell me my ball is moving more or less the way I want it to.”18 It was a far cry from his previous two years in baseball’s wasteland.

But Grimsley’s effectiveness didn’t last. Over the second half of the season he began to struggle, and through one two-week stretch in September, manager Joe Torre didn’t use him at all. Grimsley finished the regular season with a 3.60 ERA in 55 games.

There was one celebratory moment to come, however. Grimsley has been left off the postseason roster during the first two rounds of the playoffs (Yankees wins over Texas and Boston). For the World Series, vs. the Atlanta Braves, Torre made him eligible. In Game Three, at Yankee Stadium, Grimsley relieved starter Andy Pettitte in the top of the fourth inning with the Yankees trailing 5-1, two outs, and a man on first. Over the next 2⅓ innings, despite allowing two hits and surrendering two walks, Grimsley held the Braves scoreless, and New York eventually came back to win 6-5 in 10 innings. The next night, the Yankees won the World Series.

As 2000 arrived, Grimsley had a few productive years left – and several terrifying and frustrating episodes to experience. In January, he re-signed with the Yankees. After an inconsistent regular season (5.04 ERA in 63 games), Grimsley made what would be his final postseason appearances, facing Seattle in Games One and Five of New York’s victorious ALCS. He didn’t play in the World Series, and in November was released.

In January 2001, Grimsley signed with Kansas City and began what became his longest tenure with one team, pitching in 251 games over 3½ seasons for the Royals. Traded in June 2004 to the Baltimore Orioles, after the season the 36-year-old pitcher had Tommy John surgery on his pitching elbow. During his rehab period Grimsley’s first terrifying episode occurred.

In 2003 the Grimsleys had bought a house in a Kansas City suburb, Overland Park, Kansas, where the family planned to settle after his career ended. On Friday morning, January 21, 2005, Grimsley left the house to drop his boys off at school and take his car to the dealer for service. Dana was home with daughter Rayne, working out in the basement. At about 9:30 a twin-engine Cessna airplane carrying five passengers heading for a golf outing in Florida took off from an airport two miles from the Grimsleys’ house. A moment later the plane slammed into the house’s concrete foundation and tore through the porch.

“I heard it coming down,” Dana said. “I looked to my right and saw it come down. It was in a different room of the house, so I didn’t see it hit. I ran upstairs from the basement with Rayne. We called 911 and ran out.”19 Neither was injured.

Grimsley’s Nissan pickup, was parked in front of the house. When the plane hit the house, it exploded, sending a shower of shrapnel far enough down the street to cause a police blockade two blocks long. One piece slammed into the truck, which caught fire.

When he arrived, Grimsley surveyed the damage but rejected any sense of pity for the family’s loss, instead offering condolences for the passengers and admiration for the pilot. “We’re going to our friends’ house,” he said. “And that’s why we made this place our home: The people that have offered help are so gracious. But we don’t need help. I’m just concerned about the family members of the gentlemen who lost their lives. They’re the ones who need help.”

“From what I saw, at the last second you could see the pilot did everything he could to avoid the house. … You can see that from the angle the plane went in. His last thought was the safety of his passengers. And the fact is, he had the presence of mind and grace to do what he did.”20

The Grimsleys eventually repaired the house and returned.

By the summer of 2005, Grimsley was finally ready to pitch again. As he prepared to return to the Orioles’ active roster, Grimsley told a Baltimore Sun sportswriter, “I know the end is near. But this is, like, my second chance. Nobody loves going out there more than me. There’s a part of you that plays this game that never grows up. Remember ‘Field of Dreams’? Walking out there again between those white lines and chasing that dream – that’s what I want to feel.”21

Grimsley returned to work with the Orioles on July 15 and pitched in 22 games. After the season the Orioles released him.

In December the 38-year old Grimsley signed a one-year, $825,000 contract with the Arizona Diamondbacks. On May 31 the Diamondbacks were in New York to play the Mets. Arizona had been on a roll, winning 7 of their last 10 games. That night at Shea Stadium, the two teams went into the 13th inning tied 0-0. In the bottom of the inning, Grimsley, the sixth Arizona pitcher, came on in relief, faced three batters, and allowed the winning run. It turned out to be his last major-league appearance.

A week later, his career came to an end. On June 6 IRS and FBI agents, armed with a search warrant, raided Grimsley’s home in Scottsdale, Arizona, and seized numerous items: a digital phone and answering machine; cellphone; bank and credit-card statements; checkbooks, other financial records, and other electronics. It was the culmination of an investigation that had gone on for many months. In April, investigators had traced a shipment of illegal human growth hormone (HGH) to Grimsley’s home and confronted him. During interrogation, Grimsley admitted using illegal performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) as a means to circumvent baseball’s policy against illegal steroids. Grimsley also, according to later reports, named other players who were using PEDS. For that, most would never forgive him.

That night, as the Diamondbacks played the Phillies at home, Grimsley was warming up in the bullpen when he learned that his confession was soon going to be made public. The next day he asked the team to release him, confessed to his teammates, cleaned out his locker, and left the game for good. (Initially, the Diamondbacks offered to pay Grimsley the remainder of his salary, $504,000. Then they rescinded that offer. Determined to fight for his money, Grimsley eventually agreed to disburse the money among four charities.)

Had Grimsley elected to continue his career, he would have faced a mandatory 50-game suspension in 2007. Instead, he chose to retire. He was never charged with any crime. The Grimsleys returned to Overland Park determined to keep a low profile. Having made almost $10 million in his career, Grimsley was set financially. In Overland Park, he opened JOCO Baseball, an indoor batting and pitching instructional facility for youth and high school players. The academy was housed in a nondescript building that bore no marking of its owner. Additionally, Grimsley had invested with former teammate David Wells in a New York nightspot called Plum, and had also put money into a cousin’s Houston-based company that managed hospital pharmacies. Grimsley was also involved in commercial properties around Kansas City; an Internet pet supply business; and a car wash.

By all accounts Grimsley still calls Overland Park his home.

Last revised: January 21, 2019

This biography was published in “1995 Cleveland Indians: The Sleeping Giant Awakes” (SABR, 2019), edited by Joseph Wancho.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 New York Times article contained in Grimsley’s Hall of Fame player file.

2 The Sporting News, NL East Roundup, September 18, 1989: 24.

3 Ibid.

4 New York Daily News, May 18, 1999.

5 USA Today Baseball Weekly, February 23, 1993.

6 Bill Brown, NL East Roundup, The Sporting News, March 30, 1992: 14.

7 USA Today Baseball Weekly, February 23, 1993.

8 Ibid.

9 Sheldon Ocker, AL East Roundup, The Sporting News, September 13, 1993: 22.

10 Associated Press clipping dated April 12, 2004 In Grimsley’s Hall of Fame player file.

11 Chicago Sun-Times, June 8, 2006.

12 Associated Press clipping dated April 12, 2004 in Grimsley’s Hall of Fame player file.

13 Buster Olney, “Yankees Pass Pop Quiz, but Their Big Test Comes This Week”, New York Times, May 30, 1999: SP1.

14 Buster Olney, “Piniella Accuses Grimsley”, New York Times, May 10, 1999: D7.

15 Buster Olney, “Yankees Pass Pop Quiz, but Their Big Test Comes This Week”, New York Times, May 30, 1999: SP1.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Buster Olney, “Piniella Accuses Grimsley”, New York Times, May 10, 1999: D7.

19 KansasCity.com, January 22, 2005.

20 Ibid.

21 Baltimoresun.com, June 10, 2006. URL?

Full Name

Jason Alan Grimsley

Born

August 7, 1967 at Cleveland, TX (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.