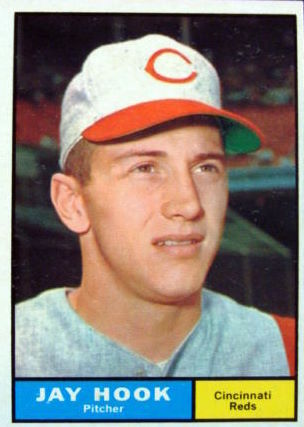

Jay Hook

Jay Hook won fewer than 30 games as a starting pitcher over parts of eight major-league seasons with the Cincinnati Reds and New York Mets, but one of those wins looms quite large in Mets history. As the 50th anniversary of the franchise rolls around in 2012, a frequently-asked trivia question is likely to be: What hurler earned the very first win in New York Mets history?

Jay Hook won fewer than 30 games as a starting pitcher over parts of eight major-league seasons with the Cincinnati Reds and New York Mets, but one of those wins looms quite large in Mets history. As the 50th anniversary of the franchise rolls around in 2012, a frequently-asked trivia question is likely to be: What hurler earned the very first win in New York Mets history?

That would be Jay Hook, a pitcher who Mets manager Casey Stengel nicknamed “Professor” because he attended Northwestern University during offseasons; who in his second career start with Cincinnati was pulled from the game despite throwing five innings of no-hit ball; who once missed half a season with the mumps and somehow ended up in the World Series; and who in one of the last starts of his career had the misfortune of being on the losing end of one of the rarest scoring feats in major-league history.

Hook’s historic Mets moment came after the expansion team lost the first nine games of the 1962 season. He won a five-hitter against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Forbes Field by a final of 9-1. Hook helped his own cause against the Pirates, who had entered the game unbeaten on the season with a 10-0 record, by going 1-for-4 at the plate with two RBIs and two runs scored.

“The main thing I remember was that if we would have lost one more, it would have been a record opening the season, and if Pittsburgh won one more, they would have had the record for wins,” Hook said recently. “I had pitched one game before that, and we had been winning in that one, but they took me out and we ended up losing. This time, I pitched a complete game.”

After the win, Stengel put Hook to work on the PR front. “After the game, he wanted me to keep talking to the press until there was no one left, so I did, and by the time I was done, everyone was gone from the clubhouse, and there was no hot water left in the showers, so I had to take a bath in the whirlpool in the trainer’s room,” Hook said.

The first victory for the Mets was career win number 18 for Hook on the way to a 29-62 career record. From his major-league debut on September 3, 1957 until his final game on May 3, 1964, he pitched 752 2/3 innings, garnering a 5.23 ERA with 394 strikeouts.

It may not sound like much, and in some quarters Hook’s name may be no more than the answer to a trivia question, but in the small town of Grayslake, Illinois, during the 1960s and 1970s, Little Leaguers with big league dreams were likely to hear the story of Jay Hook, the kid who grew up playing on the same fields as they played on, and made it all the way to the majors. (Later, to ensure they paid attention in school and did their homework, these same Little Leaguers might have been told that Hook spent his pro offseasons finishing an engineering degree at Northwestern, later earned his master’s degree in thermodynamics and went on after baseball to a successful career in the automotive and manufacturing industries.)

James Wesley (Jay) Hook was born on November 18, 1936 in Waukegan, Illinois, and spent most of his growing-up years in nearby Grayslake, at that time a town of fewer than 2,000 people that lay roughly equidistant between Chicago and Milwaukee. The Hook family name was well-known in Grayslake in those years. His parents, Cecil and Florence Hook, owned Cec’s Pharmacy in downtown Grayslake, and his uncle Everette Hook managed the town lumber yard. Hook grew up with two sisters, and was a three-sport star at Grayslake High School (now Grayslake Central), graduating in 1954. He earned an academic scholarship Northwestern, where he played baseball and basketball.

During the summers after his freshman and sophomore years, he worked at a can company in the Milwaukee area and played summer-league baseball. It was in Milwaukee in the summer of 1957 that he attended a Cincinnati Redlegs tryout at the request of a scout. “After the tryout, the scout asked me to fly to Cincinnati, so I did, and I got to throw batting practice to the team,” Hook said. “They said they wanted to sign me.”

Hook was signed under the bonus rule, so he would be passing on the minors and going directly to the big league club–1957 being the final season that aspect of the rule was in effect. “I think my first contract was for $65,000. Gabe Paul, who was the Reds’ [the team was actually called the Redlegs from 1956-1960] general manager, came out to Grayslake in August, and I signed the contract, and then Gabe said to me, “Your first two years’ salary is part of that contract–$7,000 a year.”

Hook made his major-league debut in relief less than a month later, against the St. Louis Cardinals, a game which the Reds lost 14-4. Hook, however pitched a scoreless 2 1/3 innings pitched, with two strikeouts and two walks. He also went 0-for-1 at the plate, striking out in his first career at-bat. Hook was a right-hander on the mound, but batted from the left side. He stood 6-feet-2 and is listed with a playing weight of 182 pounds.

“I don’t remember much about that game,” Hook said, “but I do remember that on the last day of that season [September 29, 1957], I got to start against the Milwaukee Braves, who had already clinched the National League championship. I pitched five innings of no-it ball against them, but [Cincinnati manager] Birdie Tebbetts came out and said, ‘You’re too young to pitch a no-hitter’ and he took me out.” Laughing at the memory, Hook added, “Well, he really just wanted to get a look at another of his young pitchers, and I think he also wanted me to feel good about myself, that I had no-hit the champs for five innings and could leave before they got to me.” (Cincinnati later lost the game, 4-3.)

Hook spent much of the following two seasons in the minors, going 13-14 for AA Nashville in 1958, while getting into one game with the big-league club. In 1959, Hook was 10-7 with a 2.96 ERA for AAA Seattle, and got the call up to Cincinnati in time to go 5-5 in 15 starts while appearing in 17 games total.

“I think Gabe Paul saw that I did a good job for him in Seattle, and he wanted me back,” Hook said. The bonus baby’s original contract was up at the end of the ‘59 season, and Paul sent Hook a new contract to sign at the same annual salary–$7,000. “I was expected to sign it, because that’s how it worked back then,” Hook said. “But, I told Gabe I had gotten married in 1957 after I signed my first contract and already had a son, and I need to pay for college after the season is over. I told him I needed the contract to be $10,400. He got all mad and said no, that $7,000 was enough. I told him ‘Okay, I’ll sign, but I’m going to have to get a second job during the offseason.’ He said ballplayers shouldn’t need second jobs, and said he’d give me $9,600 if I agreed not to get one or tell anyone I needed one—he just didn’t want that being talked about publicly.”

Hook went on to have what was probably his career-best season in 1960, going 11-18 with a 4.50 ERA, pitching 10 complete games, including the only two shutouts of his career. One of those shutouts, a 9-0 win against the Milwaukee Braves on September 20, 1960, proved significant to the pennant race, as it was widely observed as having slowed the Braves’ push for the National League crown eventually clinched by the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Hook’s final season with Cincinnati was 1961, a year that proved to be a great success for the Reds, though less so for Hook himself. Early in the season, while on a West Coast road trip, Hook did a favor for an old Grayslake friend who had moved to California: “He asked me to come out and speak to a grade school class, and I always liked doing that kind of stuff, so I did it, and I ended up getting the mumps,” Hook said. “The thing was, I didn’t know until I was in Philadelphia a few days later and got sick on the team plane. Because I exposed everyone on the plane to the mumps, they all had to get shots, so I don’t think the team was very happy with me. I ended up missing most of the season and came back only at the end.”

Hook came back just in time for the best part of the season, as Cincinnati finished in first place with a 93-61 record, providing the small-town boy with a dugout view of the 1961 World Series as the Reds faced the 109-win New York Yankees. The Reds lost the Series, 4-1, and Hook never got to throw a pitch, but did earn a National League Championship ring and a postseason pay share for his illness-shortened service that year.

Days after the 1961 World Series, Hook and his wife, Joan, were driving back to Evanston so Hook could start another round of classes at Northwestern, when he received some surprising news. “We had this nice little car, an Austin-Healey,” said Hook, whose keen interest in cars and engineering education would later lead him into his post-baseball career. “We heard on the car radio that I had been traded [actually picked in the expansion draft by the Mets]. I didn’t know what to make of it. When we got back to school, the Mets actually wanted me to come to back to New York to see a doctor right away and make sure I was okay after having the mumps, but I had to go to school, so I went to a doctor in Evanston and sent them the results.”

The first-ever Mets win the following April was, of course, one of just 40 the new team collected in 1962, against a record 120 losses. Hook posted an 8-19 record, though he led the team in complete games with a career-best 13. There were few highlights for both Hook and his new club in 1962.

Hook still has fond memories of his legendary manager’s character and upbeat attitude during that otherwise disappointing season. More than 40 years after that “losingest” season, Hook, in a newspaper commentary discussing the 2003 Detroit Tigers, who almost broke the Mets’ record for losses, said, “The Mets may have been the supreme optimists because, as a team, we always believed we were going to win the next game out.” [1]Hook credited Stengel with keeping that attitude alive all year.

Like many players, Hook occasionally found himself the target of Stengel’s sense of humor. In the foreword to the anthology Why a Curveball Curves: The Incredible Science of Sports, Robert Lipsyte, author and Mets beat writer for The New York Times in 1962, recalled how Hook was the rare man who not only knew how to throw a curveball, but could also explain in scientific terms, thanks to his education, exactly why a curveball curves. Stengel didn’t miss a chance to tweak his young charge, telling Lipsyte, “If Hook could only do what he knows.” [2]

“Casey was really interesting,” Hook said. “People talk about ‘Stengelese’—he had this way about him where he’d be talking about one subject, and his mind would jump ahead to the next thing, and he would start talking about that, but then he always remembered the first subject and came back to it. He had this amazing ability to keep track.”

As a willing public speaker who was elected the Mets player rep in 1962, Hook himself was appreciative of Stengel’s own PR skills. “One of the things Casey was so good at is that he knew who his audience was,” Hook said. “After every game, he would have the writers into his office and give them a beer. He loved to talk and he really made things easy for them. I think his willingness to do that is what contributed to the success that the Mets had in drawing a lot of fans even though we weren’t very good.”

Stengel also played a supporting role in what Hook remembered as one of the key moments in his career that he would like to have back. On June 18, 1962, Hook was pitching at the Polo Grounds in New York against Milwaukee. In the third inning, the Braves loaded the bases, and Hank Aaron came to the plate. “You know, at the Polo Grounds, it was about 500 feet to center field,” Hook said. “The bases were loaded, and the count went to 3-and-2. Casey came out and said, ‘Professor, get him to chase it low and outside. Even if he hits it, he’ll never hit it outta here.’ So I threw it low and outside, and Aaron hit it about 550 feet to center field, a grand slam.”

The following season of 1963 would be Hook’s last full season in the majors, and he appeared in a career-high 41 games, with the majority of the mound outings in relief. Hook went 4-14, and earned his only career save that season. That’s year’s highlight may have come courtesy of Hook’s hometown. During the first week of July, 1963, when the Mets traveled to Chicago to play the Cubs, the village of Grayslake honored the 26-year-old with “Jay Hook Day,” inviting Hook, manager Stengel, and all of Hook’s teammates to ride in a parade down the town’s main thoroughfare, Center Street, whose businesses included the pharmacy and lumber yard run by members of Hook’s family. (Somewhat disputed local lore has it that Center Street had been freshly paved for the occasion, and that Clydesdale horses featured in the parade ripped up the new asphalt as they trotted along—Hook said he doesn’t remember that detail. The topic of “Jay Hook Day” again became timely in Grayslake in February 2011, when the Grayslake Historical Society opened an exhibit on local athletes that featured Hook’s story, among others.)

What Hook remembers of that day is that the town coordinated activities for all of his teammates, and invited everyone to a banquet that night at a local country club. “They asked Casey to emcee the dinner, but he had to get back down to Chicago that night, so Jimmy Piersall did it instead,” Hook said. “He was hilarious. Everybody had a great time, and as a gift, the town gave me a shotgun, which I still have.”

Later in the 1963 season, Hook would experience perhaps the final intriguing and star-crossed moment of his brief career. On September 2, 1963, almost six years to the day after his debut, Hook took to the mound against the team that had brought him to the majors, Cincinnati. On the very first pitch of the game, eventual Rookie of the Year Pete Rose homered off Hook. The veteran Hook settled down to yield only three more hits and pitch the final complete game of his career–even getting a modicum of revenge from Rose by picking him off first base after a third inning single. Unfortunately, Rose’s home run proved to be the only run of the game, as the Mets lost 1-0, subdued by a 13-strikeout, complete game shutout performance by Hook’s old Cincinnati teammate Jim Maloney. It was the rare event in baseball history when all of a game’s scoring was accomplished on the very first pitch. It had not happened in almost 30 years up to that moment.

Hook doesn’t appear to have many regrets from a career that featured many more losses than wins, and such bad luck moments as his bout with the mumps, and that September 1963 loss to the Reds. “If there’s one thing I wanted to do, it was to win 20 games, just once, and I never got the chance to do that,” Hook said.

Though some “bonus babies” of the era may have faced resentment of teammates who spent years playing their way up to the big leagues, Hook said he never experienced such conflicts and had great relationships with teammates in both Cincinnati and New York. Also, while it is difficult not to highlight Hook’s advanced education compared to lack of such schooling among fellow players, Hook said he believes too much has been made of that distinction over the years. “You really couldn’t tell who the educated guys were, and who weren’t,” he said. “On the road, everybody read the paper, and a lot of guys who didn’t go to college had actually traveled to a lot of places in their playing days, so that sort of evened things out because they were more worldly in some ways.”

Because of his education, however, Hook could count on having some attractive career options when he decided to retire. That day finally came in 1964, with Hook having just enough major-league service (five full years) to qualify for a pension, and after a final stint in the minors with Milwaukee’s AAA Denver club.

Upon retirement, Hook immediately started working in product development for Chrysler. “It was fun because I was working on cars that were three or four years out,” he said. Later, a friend was starting a product planning department at Rockwell, and Hook went to work there, getting promoted over the years into management. He later joined auto and plumbing parts manufacturer Masco Corporation, where he went on to be a successful executive managing several companies until his retirement in 1992. He also taught at Northwestern. Hook and his wife raised four children, and at last count they had 13 grandchildren and two step-grandchildren. They live in Maple City, Michigan, and Jay keeps in touch with the game by talking baseball with his grandchildren.

With that kind of post-baseball resume, retiring from baseball when he did probably proved to be the most fortuitous decision of Hook’s career. “When I got into baseball, I set an objective to try to stay in the game for five years and then make a decision about it,” he said. “At the end of five years, I felt great, but my son was just starting school, and there was a lot more to think about. You didn’t make a lot of money in baseball in those days, and when you got down to it, I was just an average player.”

May 18, 2011

Sources

Unless otherwise indicated, all Jay Hook quotes come from an interview conducted by the author on April 18, 2011.

Baseball-Reference.com

Baseball-Almanac.com

BaseballLibrary.com

NewYorkMetsHistoryOnline.com

The Ultimate Mets Database

The Grayslake Historical Society

MLB.com, “Where are they now? Jay Hook,” by Jon Blau, August 22, 2008

Newsday, “40 Years Ago, Jay Hook was an Original,” by Steve Jacobson, March 3, 2002

The New York Times, “Original Met Goes Back in Time, Reviewing Plight of the Tigers,” by Ira Berkow, September 28, 2003

Why a Curveball Curves: The Incredible Science of Sports, edited by Frank Vizard, foreword by Robert Lipsyte. (Hearst Books, 2009)

Los Angeles Times, “In Baseball or in Life, Win or Lose, You’ve Got a New Game Every Day,” by Jay Hook, September 23, 2003

Full Name

James Wesley Hook

Born

November 18, 1936 at Waukegan, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.