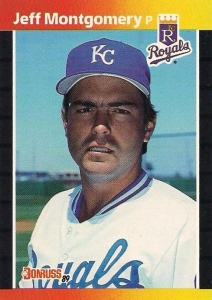

Jeff Montgomery

When Jeff Montgomery took the mound for the Cincinnati Reds on August 1, 1987, he was living out the storybook baseball tale. A three-sport athlete from small Wellston, Ohio, Montgomery grew up a couple of hours down the road from Riverfront Stadium in the era of the Big Red Machine. His idol, Reds manager Pete Rose, handed him the ball on that day, and Montgomery threw two innings in his major-league debut.

When Jeff Montgomery took the mound for the Cincinnati Reds on August 1, 1987, he was living out the storybook baseball tale. A three-sport athlete from small Wellston, Ohio, Montgomery grew up a couple of hours down the road from Riverfront Stadium in the era of the Big Red Machine. His idol, Reds manager Pete Rose, handed him the ball on that day, and Montgomery threw two innings in his major-league debut.

Six months later, he was traded.

Montgomery’s path to the big leagues was lined with obstacles and opportunities. When the dust settled, he was a member of the Kansas City Royals Hall of Fame, and the second major leaguer to reach 300 saves with only one team.1

Montgomery was born in Wellston on January 7, 1962, to Tom and Mary Montgomery. Tom worked in the coal industry and later started a construction company. He coached Jeff’s football team in junior high, and his American Legion teams during high-school summers. Mary was an office manager at Wellston’s Pillsbury plant. At Wellston High, Montgomery lettered four years each in baseball and football, starting at quarterback and safety and later making the All-Ohio football team on defense. He also worked as Wellston’s placekicker. He lettered in basketball three years, averaging 12.7 points per game. When he graduated in 1980, he held or shared 18 school records.2

Montgomery’s achievements in high school earned him a spot in Wellston’s Athletic Hall of Fame, the 1980 inaugural Willard Fitzpatrick Award as selected by the Southeastern Ohio League Sports Writers and Broadcasters Association, and, later, his own street in Wellston — Jeff Montgomery Way. The Reds were Montgomery’s team, as would be expected, and he grew up a fan of Reds pitchers Gary Nolan and Don Gullett while also idolizing Rose.

Montgomery’s high-school coach, Pat Hendershot, made sure his team had ample opportunity to play. That enabled Montgomery to play on the high-school team, summer Pony League teams, the American Legion team, and even on men’s semipro teams as early as age 15. As a shortstop and right-handed pitcher, he led Wellston’s Rockets, drawing interest from Ohio University, Ohio State University, and Miami of Ohio. While Ohio State was Montgomery’s first choice, a Reds scout had tipped off Marshall University coach Jack Cook and the university offered Montgomery a baseball scholarship. When the other schools didn’t match it, Montgomery went to Marshall.

As a freshman at a smaller school, he was able to “hit the ground running,”3 and his college career got off to a hot start. Montgomery threw a one-hit shutout in his first start as a freshman, finishing with four complete games in his first season. After striking out 57 in 56 innings with a 3.27 ERA in 12 starts, Montgomery earned the Southern Conference Freshman of the Year award.4 He struggled in his junior year, but a few chance appearances in front of scouts paved his way to the big leagues.

“I pitched a game against the University of Kentucky and there were scouts at the game to watch some players on Kentucky’s team. I believe I threw a shutout against them in that game, so the next game I pitched was against Ohio University and that game they came to see me pitch.”5 This led to a tryout with the Reds two weeks before the 1983 draft. On draft day, Montgomery was golfing with his father when his mother and sister began waving their arms. They had a telegram informing Jeff that he’d been selected with the Reds’ ninth-round pick.

The Reds initially offered Montgomery $1,000 to sign and start his pro career, but with a year left on his scholarship, he was able to leverage another year of college eligibility into a $9,000 signing bonus, the estimated value of one year of a scholarship.6 This was not be the first time Montgomery’s pursuit of a degree would pay off for his baseball career.

Montgomery joined the rookie-league Billings Mustangs in 1983 (he’d finish a computer-science degree at Marshall during the offseason after the 1983 and 1984 seasons) and made a great first impression. Mustangs manager Marc Bombard approached Montgomery about a shift to the bullpen in a post-draft minicamp. A starter all through high school and college, Montgomery was initially reluctant to move to the bullpen, unsure of how his arm would hold up. But he took to the change quickly and credited it as one of the best things that could have happened to him.7 Bombard himself noted that a shift to the bullpen allowed him to use Montgomery to impact more games, and could put him on the fast track to the majors.8 In 44⅔ innings, Montgomery struck out 90 batters. His strong pro debut placed him ninth on Baseball America’s ranking of Reds prospects.

Montgomery opened the 1984 season with Class-A Tampa and pitched well enough to make the Florida State League All-Star Game, which he won after two innings pitched in relief. Two days later, he was called up to Double-A Vermont, still coming out of the bullpen. Between both levels that year, he threw 69⅔ innings and finished with a 2.33 ERA. He moved up in Baseball America’s rankings that year, now the seventh-best prospect in the Reds’ system. After repeating 1985 in Vermont, Montgomery advanced to Triple-A Denver.

He started in the bullpen again in 1986, but eventually shifted from a role as a long reliever to a starter after a series of doubleheaders and rainouts put him into the rotation.9 The notorious Denver thin air and altitude affected his performance, and after a 4.39 ERA (the first time it rose above 3.00), Montgomery was invited by Frank Funk, the Royals pitching coach, to play winter ball in Puerto Rico.

At the time, Montgomery had been in the Reds organization for a few years but didn’t feel close to the majors. He and his wife, Tina, were parents now and he needed assurance that a shot would be coming, or his Triple-A salary needed to increase. Sheldon “Chief” Bender, head of the Reds’ scouting department, told him there would be a new contract once he returned from winter ball. After returning from Puerto Rico with the contract unchanged, Montgomery started to look for a career outside of baseball, and in early 1987 had even interviewed to be a systems analyst with Hershey Chocolate.10

Montgomery’s college degree again gave him some leverage and he got an invitation to big-league spring training as a nonroster player. Montgomery had finished the 1986 season strong with Denver and put up a 2.72 ERA in winter ball,11 but ended up assigned to Triple-A Nashville (after 1986, the Reds moved their Triple-A affiliate out of Denver) for the 1987 season.

Avoiding Denver for a second season improved Montgomery’s numbers, and he was one of the best starters in the American Association. In July he returned to the bullpen, with speculation being that the Reds wanted to see him in a relief role at a high minor-league level. In late July, Montgomery led the American Association in strikeouts and ERA which led to his contract being purchased on July 29, 1987. He made his major-league debut on August 1.

That led to Pete Rose, childhood idol, handing him the ball.

Later in August, Montgomery was tapped to make a start for the Reds, giving up five runs in five innings in a loss for Cincinnati. It was his only major-league start. For the remainder of the year, Montgomery pitched out of the bullpen, rounding out his first major-league action with 19⅓ innings and a 6.52 ERA.

Despite his passable performance in Triple A and in a big-league bullpen, the Reds didn’t see a spot for Montgomery in their future pitching staff. Reds general manager Murray Cook told him that Rose handed the front office a list of players who he didn’t think could play for him, a list that included Montgomery.12 The rumor — told with tongue mostly in cheek — was that Rose had bet on Montgomery’s big-league start and it put him in the “doghouse.”

The Reds came to a deal in February 1988 to send Montgomery to the Kansas City Royals in exchange for Triple-A outfielder Van Snider. Montgomery had drawn the attention of then-Omaha-now-Kansas City manager John Wathan in 1987 during a Nashville-Omaha matchup, and pitching coach Frank Funk had already seen Montgomery and his mix of pitches in Puerto Rico. At the same time, Snider had impressive performances for Omaha against Nashville, piquing the Reds’ interest.

The trade made Montgomery “the happiest player in baseball.”13 Just as he reported to spring training, general manager John Schuerholz told him the Royals planned to send him to Omaha to work out of the bullpen. After two months of dominating for Omaha, Montgomery was called up for good. Joining a bullpen led by former All-Star Dan Quisenberry, Montgomery had a strong showing and was named as part of Baseball Digest’s All-Rookie team after 62⅔ innings and a 3.45 ERA.14

The strong Royals rookie season led to Montgomery’s earning an important spot in Kansas City’s bullpen in 1989, helping set up for Steve Farr, who had inherited the closer’s job after Quisenberry was released in the middle of 1988. Montgomery started closing games regularly in June and held the role while Farr recovered from knee surgery later in the year. At 5-feet-11, Montgomery’s short stature and low-90s fastball didn’t portray the image of the dominant, fireballing closer, and his presence in Kansas City led to a relative anonymity that he joked may have helped him out during the successful season. After 18 saves and a 1.37 ERA, manager Wathan stated that Montgomery had the inside track to the closer’s job.15

However, after the Royals fell short of the playoffs (despite the second-best record in the American League) GM Schuerholz, recalling the dominance of the Royals with Quisenberry at the back of the bullpen in the early 1980s, pursued and ultimately signed 1989’s National League Cy Young Award winner Mark Davis.16 After getting 44 saves for the San Diego Padres, Davis earned the highest one-year salary in baseball ($2,125,000), joining Bret Saberhagen, the American League’s winner, on the Royals. The Davis signing made the Royals the first team to have both reigning Cy Young Award winners on their roster. Multiple publications had the Royals picked for a pennant or championship for the 1990 season.

While the team had improved on paper, the acquisition was frustrating for Montgomery, who voiced displeasure about losing a role he’d barely held. “I’m on the best pitching staff in baseball and wanting to leave it,” he told one reporter.17

Montgomery continued to work on being the best setup reliever in baseball, and by May of 1990 he had regained the closer’s job after Davis faltered. Shoddy command and slight injuries made Davis ineffective, and by July the Royals were already experimenting with Davis in the rotation.18 Montgomery saved 24 games.

With two-plus years of success, Montgomery started 1991 as the closer, but during spring training Wathan wouldn’t commit full-time to him. A Montgomery/Davis platoon tandem was floated as well. Still, Montgomery started with the job and his performance gave no reason to make a change. While the Royals started the year 15-22, Montgomery had saved nine of the wins. But the slow start cost Wathan his job and he was replaced by former Royals DH Hal McRae.

It was with McRae at the helm that Montgomery finally cemented his closer status, though it wasn’t without its speed bumps early on. In McRae’s first week, in a May 28, 1991, game against Seattle, Montgomery entered in the eighth inning to protect a 6-4 lead. In the ninth he recorded the first two outs easily, but an 0-and-2 pitch to Edgar Martinez found the bat and dropped softly into right field for a single. With Ken Griffey Jr. coming up, McRae walked out. When McRae asked for the ball, stating “[Davis] is making too much money down there not to be in this ballgame,” Montgomery replied that it would take a bulldozer to get him out of the game.19 Reluctantly, Montgomery handed the ball over.

When Davis came in, he walked Griffey on four pitches, then gave up a single to make it 6-5 and put the tying run on second. He managed to get a strikeout to preserve the lead, but within the clubhouse, Montgomery’s frustrations boiled over. Equipment was thrown, words were yelled, and Montgomery “was not happy at all.”20

After the game, McRae talked to Montgomery in his office and told Montgomery he was the team’s closer. He finished the year with 33 saves.

Buoyed by the trust of his manager and ballclub, Montgomery entered 1992 officially in his coveted role. After 21 saves and a 1.60 ERA, Montgomery made his first All-Star team, traveling with McRae (selected as a coach) to San Diego. On July 24 Montgomery recorded his 100th career save against Cleveland.21

In February of 1993, Montgomery signed a three-year, $11 million contract that kept him a Royal through 1995. The Royals also held an option for the 1996 season. Montgomery expressed contentment at the commitment the team had made, and Barry Meister, his agent, noted that it was the second largest relief-pitcher contract to that point.22 He again made the All-Star team in 1993, recording 25 saves in the first half of the season, which put him on pace to eclipse Quisenberry’s team-record 45 saves set in 1983. From May 25 through August 9, Montgomery converted 24 straight save opportunities and finished the year with 45 saves, tying Quisenberry and leading the American League. Montgomery was also named the 1993 Rolaids Relief Man of the Year and finished 13th in AL MVP voting.

The Royals’ 84-78 record in 1993 was reason for optimism, but the team was headed for a period of transition. On August 1, 1993, founder and owner Ewing Kauffman died after a brief battle with cancer, a loss felt deeply in the Kansas City community and by the Royals. Kauffman had long covered the team’s losses from his personal wealth, allowing the team to pursue the right free agents when the time called for it. Kauffman’s death meant that the team would be under the watch of a board of directors, but an official owner wouldn’t be found until 2000.

Along with Kauffman, the Royals would be without their franchise’s greatest player: George Brett retired at the end of the 1993 season after 21 years with the team. The Royals found themselves without their franchise player and their owner, and, in 1994, staring at the possibility of a strike.

Spring training started normally in 1994, but toward the end of March, Montgomery began experiencing back tightness. In April he developed shoulder soreness. At first, it was attributed to the cold of the early season, but he had also slightly adjusted his mechanics to compensate for the back pain. He would fight shoulder issues all year, with concerns over his velocity popping up in May. He received a cortisone shot for bursitis in June.23

After treatment, however, Montgomery’s “zip” returned and he converted a string of saves in July. By the end of July, he’d closed out 13 straight chances and, when the Royals went on a 14-game winning streak, Montgomery had saves in eight of the wins.

However, the business of baseball interrupted the Royals’ surge. As the team’s player representative, Montgomery mentioned numerous times through the year that a strike was a possibility, and in late July, an August 12 strike date was set. When no agreement was found between the owners and the players union, the players went on strike. Despite initial optimism that games might resume, the season was canceled along with the playoffs on September 15. The next day, the Royals fired manager McRae.

Replacing McRae was Bob Boone, whom Montgomery had played with early in his Royals career. But before Boone could lead his team, the labor strife had doomed the Royals. After losing revenue because of the loss of the last six weeks of the 1994 season and playoff revenue shared through the league, the Royals found themselves in financial trouble. With no Ewing Kauffman to cover the team’s financial losses, and with the need to remain attractive to a new owner, the team entered 1995 looking to shed payroll.

After the players returned in April, the Royals dealt away two veterans in the span of 24 hours, trading off Brian McRae to the Cubs and David Cone — 1994’s Cy Young Award winner — to Toronto. After the delayed start to the season, the post-strike Royals looked much different, and any optimism left from the pre-strike surge was gone. The team seemed to be in a fog to open the year, though it hovered around .500 most of the season. During that 1995 season, Montgomery still anchored the bullpen, notching his 200th career save on June 21.

Late in the 1995 season, the Royals again shook up the roster, dumping Vince Coleman, Chris James, and Pat Borders while calling up Johnny Damon and Michael Tucker. At the time the Royals were in the wild-card hunt, but the sudden moves toward a youth movement led to skepticism from some veterans, including Montgomery.24

In November 1995 Montgomery filed for free agency. Earlier in the year, he had stated a preference for staying in Kansas City and had even offered to take a pay cut in exchange for a reworked deal that would offer more long-term security.25 But he also noted that he didn’t anticipate playing in the big leagues much longer. With no postseason experience, he wanted to monitor what other Royals veterans did, as well as how the market unfolded for other closers. After evaluating other offers, he returned to Kansas City, agreeing to a $4.75 million deal for 1996 and 1997 over a $6 million offer for two years from Toronto.26

On one hand, Montgomery turned down more money, but as he described it, the difference in money was secondary to staying in a place where he’d built a home and started a family.

As the 1996 season opened, Montgomery was in range of Dan Quisenberry’s team record for career saves. But the Royals started slowly and the bullpen “bridge” to Montgomery was shaky, limiting his opportunities. He was also his own worst enemy early in the season, blowing saves while his velocity dipped. In late June, he was still four saves behind Quisenberry and his slump continued into July. Manager Bob Boone tried to rest Montgomery, they tried to vary his pitch patterns, Montgomery did extra work on his mechanics. Anything to find the missing element.

Despite the struggles, Montgomery was selected for the American League All-Star team, his third selection. He had 18 saves in the first half of 1996 and on July 17 tied Quisenberry’s 238 saves, closing out a 3-2 win against Cleveland. On July 20 he secured his 239th save as a Royal, a new team record. The save was a typical Montgomery save: a mix of four pitches, a baserunner, but eventually the Royals shaking hands at the end. The record was particularly special for Montgomery since Quisenberry had been helpful as a teammate when Montgomery joined the Royals in 1988 and the two lived in the same community and went on a golfing trip every year.27

The rest of the 1996 season was fraught with difficulty. In August Montgomery pitched in eight games and gave up four home runs. The shoulder bursitis that had emerged in 1994 had been a recurring problem and he tried another cortisone shot in August 1996. His frustration was evident and after one appearance in September, Montgomery was shut down for the rest of the season. It was thought at first that rest might be enough to curb swelling in the shoulder, but eventually surgery was recommended.

The surgery was intended to shave down a bone spur in Montgomery’s shoulder, but Dr. Steve Joyce also found a frayed tendon in the rotator cuff and a partial tear in the labrum. It was more damage than anticipated, and while everyone was optimistic, it was still major shoulder surgery.

Montgomery made Opening Day 1997 his goal. To get there, he needed to go through extensive rehab in the offseason. He worked to strengthen his shoulder every day, and starting in January and going into spring training, the Royals carefully monitored his velocity any time he threw.

It was encouraging, and Boone noted that Montgomery’s arm slot had returned to where it had been years ago. While Montgomery usually worked around 90 mph with his fastball, in spring training he was regularly around 92 or 93 mph. In mid-March he threw his first inning in a spring-training game without holding back. Still, he remarked that he wasn’t entirely convinced he’d make it back to the big leagues. His goal was to make the big-league roster, but the Royals conceded that he might need more work at the spring-training facility before joining the big-league club. However, Montgomery suffered no setbacks and joined the Royals as the season started in April.

In his first five games of 1997, Montgomery gave up three homers in 4⅓ innings and had an ERA of 16.62. Boone and others suggested the conditioning wasn’t there yet, and his breaking pitches were flat. Montgomery spoke with Boone and pitching coach Bruce Kison about potential retirement, but they persuaded him to go on the disabled list to work through it instead.28 On April 18, he was placed on the DL.

The setback was particularly frustrating after the work he’d put in, but Montgomery persisted. While throwing a simulated game toward the end of April, Montgomery threw “free and easy” without a radar gun for a change and felt the familiar command of his pitches again. He returned to Omaha for a brief stint before returning to the Royals on May 4.

In his first appearance back, he gave up four runs, but Montgomery’s next four outings were scoreless appearances and once June started, he was showing signs of returning to form. From June 4 through the rest of the season, Montgomery put up a 1.45 ERA over 43⅓ innings, including a stretch of 32 straight batters retired over a three-week stretch. New manager Tony Muser (who replaced Boone over the All-Star break) remained committed to Montgomery as the closer. The strong second half led the Royals to exercise their option to keep Montgomery for the 1998 season, and with surgery and rehab behind him, the club had high expectations for him to be as good as ever.

Montgomery had the same high expectations heading into 1998, stating that he felt as good physically as he had in 1993, before any bursitis issues. On Opening Day he closed out a win in Baltimore for his first save. In his second appearance, Montgomery gave up four runs in two-thirds of an inning. The rest of his first half featured stretches of scoreless pitching marred by strings of games in which he gave up multiple runs. After giving up three runs on June 15, he had an ERA of 8.10.

Muser suggested that Montgomery was suffering from dead arm. Montgomery expressed shaken confidence.

Multiple issues were cited. Rushing pitches. Mechanics. But his repaired shoulder felt fine. After refocusing on stride length and arm slot, Montgomery felt confident he’d sorted things out.

The results suggested that to be the case. From June 17 through August 6, Montgomery converted 15 consecutive save opportunities, allowing just one earned run in 16⅔ innings. He finished the season with a 4.98 ERA with 36 saves, but in the second half, he’d put up a 3.46 ERA. The season earned him the honor of being named the Royals pitcher of the year for 1998, the only time he won the award.

Montgomery was a free agent again, and the Royals made him a one-year offer. However, out of the offers Montgomery had received by late November, the Royals had offered the lowest salary.29

With no experience in the postseason, and with Kansas City amid a perpetual rebuild, Montgomery’s decision was a difficult one. His family and home were in Kansas City, and the same concerns about uprooting his children that had led him to stay for less money after 1995 were still present. But contenders were offering him more money and the opportunity to set up or close by committee in their bullpen. Montgomery posed the dilemma thusly to the Kansas City Star: “I, personally, would prefer to be a closer. But do I want 35 or 40 saves, or do I want to be playing in October?”30

Montgomery ultimately stayed with the Royals on a one-year deal with a base salary of $2.5 million (after the Royals had initially offered a reported $2 million). He was close to signing with Baltimore, though, going so far as to compare schedules to see when his travel might overlap with the opportunity to see his children back in Kansas City. One factor that steered him back to Kansas City was that Baltimore had already signed reliever Mike Timlin and the Orioles couldn’t guarantee that Montgomery would close for them. He returned to Kansas City eight saves short of 300 for his career and as the only pitcher in baseball to lead his team in saves in every season of the 1990s to that point.

Montgomery got save number 293 early in the 1999 season, but the Royals bullpen struggled early, and he often went two or more days between outings. After blowing saves on April 17 and 23, the Royals went to rookie Jose Santiago for their next save chance. In May, Montgomery worked four save opportunities, converting three but blowing a save on May 31 that would put his ERA above 5.00. It remained above that level the rest of the year.

As the Royals and Montgomery struggled, they went to a bullpen-by-committee approach. For Montgomery (who always felt sharper with more consistent work) he often spent days between outings. Montgomery was critical of manager Tony Muser, but local media columns pointed out that his performance didn’t warrant much more work either.31

In early July, Montgomery’s hip started to give him trouble, and after two blown saves, he went on the disabled list on the 9th. He had saved five games and blown five saves to that point with a 7.54 ERA.

Montgomery had often said in the later years of his career that he’d think about retirement when his wife or the batters told him it was time. In 1999 the hitters of the American League were shouting the message. While rehabbing ahead of a return from the DL, Montgomery hinted that 1999 would likely be his last season.32 General manager Herk Robinson told a reporter that the Royals would be unlikely to be able to fit Montgomery into their 2000 budget.33 It was also reported that Montgomery hadn’t talked to the Royals about the next year either.

On August 10 Montgomery returned from his rehab assignment and pitched in three games before his first save opportunity. On August 18 he threw a scoreless inning against the Yankees for career save number 298. The next night he earned save 299 with a scoreless 11th inning.

Montgomery wouldn’t pitch again until August 24 but gave up a run on three hits and blew a 3-2 lead against the Orioles. The next night the Royals led Baltimore 8-5, but Brad Rigby opened the ninth inning by surrendering a home run. Lefty Tim Byrdak came in to retire Rich Amaral and Brady Anderson. Montgomery was summoned for the right-handed-hitting Mike Bordick.

One of the hallmarks of Montgomery’s career was the tense save. Number 300 was no different. Bordick singled to center on a 2-and-1 pitch, then B.J. Surhoff followed with a single to right. With the Royals leading 8-6, Albert Belle stepped to the plate, representing the go-ahead run. The night before, Belle had homered in the 10th inning to give the Orioles the win.

Montgomery’s first pitch was a called strike. Belle chopped the second pitch to shortstop, where Rey Sanchez fielded and threw him out.34 Montgomery shook hands with his teammates after save number 300, the 10th pitcher to reach the milestone and the first to do so with every save coming with one team. Again, the topic of retirement came up and this time Montgomery was more direct, stating that 1999 would be his final year.

On September 20, Montgomery retired all four batters he faced to earn his 12th save of the year and 304th (and final) save of his career. Four days later he confirmed that he would retire at season’s end.35 Montgomery entered an October 2 game against the Tigers at Kauffman Stadium — the 700th appearance of his career — with one out in the ninth, struck out Dean Palmer and induced a groundout from Damion Easley. That turned out to be his final appearance, as the final game of the year was rained out.

Montgomery finished his career with 304 saves, a franchise-leading 686 appearances, and a 3.27 ERA in 868⅔ innings pitched. He was named an All-Star three times. While he was honored to be on the ballot for the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2005, he conceded that he wasn’t likely to be inducted (he received two votes).36 The Royals did honor him with induction into their team Hall of Fame in 2003, and Montgomery threw out the ceremonial first pitch to his father before an August 3 game. 37

While Montgomery had mentioned the possibility of becoming a baseball agent upon retirement, his post-baseball career has been more involved with the media than player negotiations. He bought a share of Kansas City’s Union Broadcasting in 1998 and as of late 2018 was their acting vice president of internet and new media. Montgomery was also a co-host of Royals Live! on Fox Sports Kansas City, appearing on the pregame and postgame show, and occasionally appearing on game broadcasts as a color commentator. As of 2018 Montgomery and his wife, Tina, lived in Kansas City.

Sources

Along with sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted the yearly game logs and player pages on Baseball-Reference.com as well as the following book:

Jacobs, Dr. Andrew, Jeff Montgomery, and Peter D. Malone. Just Let ’Em Play: Guiding Parents, Coaches, and Athletes Through Youth Sports (Olathe, Kansas: Ascend Books, 2015).

Notes

1 Dennis Eckersley had 320 saves for the Oakland A’s.

2 “Wellston Senior Wins Award,” Chillicothe (Ohio) Gazette, May 21, 1980.

3 Jeff Montgomery, telephone interview, September 8, 2018 (Montgomery interview).

4 “Haywood Top Coach,” Greenville (South Carolina) News, June 3, 1981.

5 Montgomery interview.

6 Montgomery interview.

7 Montgomery interview.

8 Dave Trimmer, “Montgomery’s Arm Needs Little Relief,” Billings (Montana) Gazette, August 20, 1983.

9 Montgomery interview.

10 Jeff Montgomery, If These Walls Could Talk: Stories From the Kansas City Royals Dugout, Locker Room, and Press Box (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2017), 199.

11 Bud Burns, “Montgomery Likes Lind, His New Club,” The Tennessean (Nashville), April 8, 1987.

12 Montgomery, If These Walls Could Talk, 201.

13 Montgomery interview.

14 Bud Burns, “Reds’ Murphy No Longer an ‘Untouchable,’” The Tennessean, November 8, 1988.

15 The Sporting News, October 9, 1989: 17.

16 Tracy Ringolsby. “Mark Davis at the Top of KC’s Shopping List,” Glens Falls (New York) Post-Star, November 26, 1989: 41.

17 The Sporting News, January 1, 1990: 50.

18 “Royals to Give Mark Davis Nod as Starter,” Macon (Missouri) Chronicle-Herald, July 6, 1990.

19 Montgomery interview..

20 Montgomery interview..

21 “Kansas City Royals at Cleveland Indians Box Score, July 24, 1992”

baseball-reference.com/boxes/CLE/CLE199207240.shtml.

22 Dick Kaegel, “Montgomery Signs for Three Years,” Kansas City Star, February 16, 1993.

23 Jeffrey Flanagan, “Royals Report,” Kansas City Star, June 20, 1994.

24 Jason Whitlock, “OK, Herk, Keep ’em Coming,” Kansas City Star, August 13, 1995.

25 Dick Kaegel, “Montgomery Backs Off,” Kansas City Star, July 16, 1995.

26 Jeffrey Flanagan, “Royals Retain Closer,” Kansas City Star, December 16, 1995.

27 LaVelle E. Neal III, “Montgomery Passes Friend on His Way to Saves Record,” Kansas City Star, July 21, 1996.

28 Montgomery interview.

29 Howard Richman, “Montgomery Pitcher of Year,” Kansas City Star, November 20, 1998.

30 Ibid.

31 Dick Kaegel, “Appier’s Streak Ends,” Kansas City Star, June 3, 1999; Joe Posnanski, “Please Keep Comments, Pitches Down,” Kansas City Star, June 4, 1999.

32 Steve Rock, “Monty Starts Rehab,” Kansas City Star, August 1, 1999.

33 Jeffrey Flanagan, “Royals’ Plans for 2000 Season Won’t Include Montgomery,” Kansas City Star, August 27, 1999.

34 “Baltimore Orioles at Kansas City Royals Box Score, August 25, 1999”

baseball-reference.com/boxes/KCA/KCA199908250.shtml.

35 Dick Kaegel, “Monty Says He’s Out,” Kansas City Star, September 24, 1999.

36 Dick Kaegel, “Montgomery Honored by Candidacy,”

web.archive.org/web/20121006110838/http://kansascity.royals.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?

ymd=20041223&content_id=925571&vkey=news_kc&fext=.jsp&c_id=kc (accessed October 30, 2018).

37 David Boyce, “Royals Induct Montgomery/Ex-Closer Relishes Hall of Fame Honor with His Family,” Kansas City Star, August 3, 2003.

Full Name

Jeffrey Thomas Montgomery

Born

January 7, 1962 at Wellston, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.