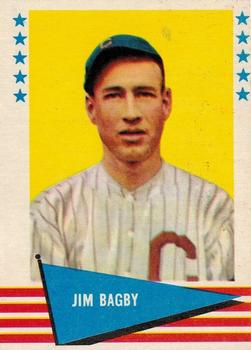

Jim Bagby Sr.

Ty Cobb once called Jim Bagby “the smartest pitcher he ever faced.” Bagby was a star as both a starter and reliever, noted for his fadeaway pitch and outstanding control. He is best remembered for his 1920 season, when he went 31-12 and led the Indians to their first pennant and first World Series victory.

Ty Cobb once called Jim Bagby “the smartest pitcher he ever faced.” Bagby was a star as both a starter and reliever, noted for his fadeaway pitch and outstanding control. He is best remembered for his 1920 season, when he went 31-12 and led the Indians to their first pennant and first World Series victory.

James Charles Jacob Bagby was born on October 5, 1889, in Barnett, Georgia. He had at least one brother and one sister. He was righthanded and stood six feet tall, weighing 170 pounds. Jim broke into pro baseball with Augusta of the Sally League in 1910, but was quickly transferred to Hattiesburg of the Cotton States League, where he went 5-11. Pitching for the same team in 1911, he improved to 22-16.

He made his major league debut with Cincinnati on April 22, 1912, at age 22. In six innings of relief he surrendered no runs, struck out two and had three assists while his team came back to beat the Cardinals 9-6. He lost his only start in the second half of a doubleheader with the Cubs on May 30. He was blasted for four runs in the first and didn’t come back for the second inning. In five games he went 2-1 with a 3.12 ERA and was demoted to the minors for the next three years.

He earned his way back to the majors by winning 20 games for New Orleans in 1914 and 19 more the following year. That season he batted .270 and played some outfield. Jim always claimed his biggest baseball thrill was on opening day of 1915 in Atlanta, when he pitched a no-hitter through 8 2/3 innings in front of his hometown crowd.

New Orleans was part of Cleveland owner Charles Somers’ proto-farm system, and Bagby made the Indians in 1916, where he would star for seven seasons. His Cleveland debut was also Hall of Fame center fielder Tris Speaker’s first game for the Indians. Bagby gave up two runs in four innings of relief as the Indians lost to the Browns 6-1 in the April 12 opening day contest. Jim went 16-17 for a .500 Cleveland club that year, pitching about half his games in relief and half as a starter. He finished in the top 10 in games, saves, and shutouts. Bagby also claimed his place as one of the best control artists of his day, finishing in the top 10 in walks per nine innings, a ranking he would claim four more times. On the flip side, although Bagby rarely walked a batter, he never struck out more than 88 batters in a season.

In many ways, 1917 was his best season. He went 23-13, tossed eight shutouts and added seven saves in 12 relief appearances. On August 6, with the Indians leading the Red Sox 2-0 in the ninth, he relieved Ed Klepfer with the bases full and one out. He fanned the next two hitters to save the game. Bagby’s 1.99 ERA was sixth in the league and he was fourth in innings pitched as the Indians rose to third place, 22 games above .500.

Around this time Bagby acquired the nickname “Sarge.” This wasn’t a Great War moniker; he never served in the armed forces. According to James K. Skipper’s Baseball Nicknames, “Sergeant Jimmy Bagby” was a character in a Broadway play some of his Cleveland teammates had seen. Irvin S. Cobb had a character with this name in his series of “Judge Priest” stories, featured in the Saturday Evening Post in the ‘teens; that may have been the genesis of the play.

Through 1918 and 1919 Bagby continued to throw a ton of innings, win and save a lot of games, and help his team to second-place finishes. On May 11, 1918, he matched up with Walter Johnson. Each pitcher gave up four hits. Each helped his own cause, Bagby lacing a double and a single, while Johnson tripled in the sixth inning and scored the game’s only run to beat Bagby 1-0.

As an example of his usage in this period, over 17 days from June 23 to July 9, 1918, Bagby pitched in 11 of his team’s 18 games. Four were complete-game starts; seven were relief appearances. He went 2-4 and saved four games, pitching 62 innings and allowing 18 runs.

Nineteen-twenty was Bagby’s most memorable season and perhaps the most eventful in Cleveland Indians’ history. He won his first eight decisions; by late June he was 14-2. On July 19 he pitched in both games of a doubleheader. He beat Boston in the first game with 2 2/3 innings of one-hit, no-run relief, then started the second game. He took a 4-2 lead into the eighth, when he tired and the Indians eventually lost. The next day, Bagby entered a tie game in the eighth, gave up one run and won in the eleventh.

By the end of July he was 21-5. Bagby faded a little in the summer sun, and on August 23 he lost a thirteen-inning complete game to Boston, 4-3. He bounced back four days later, winning an eight-hitter against Philadelphia 15-3. His record now stood at 24-9.

The Indians were in first place on August 16 when they faced the third-place Yankees in New York. In the fifth, Cleveland shortstop Ray Chapman was beaned by submarine righthander Carl Mays. He died early the next morning, the only major leaguer ever killed by a pitch.

With the Indians fighting the Yankees and White Sox for the pennant, the game against New York on September 11, 1920, established a League Park attendance record of 30,805. Bagby lost, 6-2; he was 27-10. Bagby tossed another gem, a three-hitter, on September 15 against the Athletics, but the Tribe trailed New York in the pennant race with Chicago a close third.

Beginning that day, the Indians won 14 of their last 18 games. Bagby won his thirtieth over the Browns on September 28, the same day the Black Sox were indicted and suspended. The pennant was in the Indians’ grasp with three games left and a one-game lead. On October 2 Bagby beat the Tigers 10-1 to clinch it. He was 31-12, and the Cleveland Indians were ready to play their first World Series.

Stan Coveleski, a 24-game winner, won the first game over the National League champions, Brooklyn. Bagby started the second game, but lost 3-0 to Burleigh Grimes. With the series tied at two games apiece, Bagby was back on the mound for game five in Cleveland, facing Grimes again.

Temporary bleachers had been installed in League Park for the Series, shortening the right- and center field fences. Manager Tris Speaker instructed Bagby on how to pitch taking this situation into account. Bagby piped up, “I think I’ll bust one out to those wooden seats. They seem just about right for me to hit” (Sowell, p. 272). Bagby was not a bad hitter; he had delivered seven hits in eleven at bats in late August and early September and had hit .252 for the season.

In one of the most remarkable games in Series history, Elmer Smith hit the first World Series grand slam off Grimes in the first inning. Bagby shut down the Dodgers, and was leading 4-0 when he came to bat in the fourth inning with Doc Johnston and Steve O’Neill on base. Bagby pounded the ball over the center field fence for the first World Series homer by a pitcher. In the fifth, Cleveland second baseman Bill Wambsganss turned the first (and still the only) unassisted triple play in Series history. The Indians won 8-1 and took the next two to win the Series five games to two.

Bagby rose to the occasion with a 1.80 ERA, walking one and striking out three. During the regular season he led the league in wins, won-loss percentage, games, complete games and innings. His 2.89 ERA was fifth best, and he tossed three shutouts. The only other AL pitcher who could have laid claim to a better year was Bagby’s teammate, Coveleski, with his 24 wins and 2.49 ERA.

Sarge was always a scrapper, but would sometimes claim his manager was trying to ruin him. When he grumbled about a sore arm, Speaker would reply, “What difference does that make? With all that stuff you’ve got you don’t have to bother how your arm feels.” Later in life, when asked if the pitching workload was tough on him and Coveleski, Bagby replied, “Oh, occasionally, we’d go after only one or two days’ rest, but usually we had plenty. It didn’t hurt us, anyhow.” (Atlanta Journal Constitution, 10/6/48).

This may or may not have been true; Coveleski went on to further pitching glory, but Bagby was never remotely the same pitcher again after 1920. He had a decent 1921, going 14-12 with a worst than average ERA in less than 200 innings for the second-place defending champions. In 1922 Bagby hit the wall, his ERA ballooning to 6.32. (He also had an emergency appendectomy in August.) He was sold to Pittsburgh on November 5. In 1923 he went 3-2 in limited action, finishing his big-league career with a 127-89 record.

After his season in Pittsburgh, Bagby played for minor league teams in Seattle, Atlanta, Rochester, Jersey City, Newark (a team managed by Speaker), Monroe, and York before he quit after the 1930 season. In retirement, he ran a dry cleaning establishment in Atlanta for 14 years, then a gas station for another year.

In 1941 baseball again beckoned, and Jim began umpiring for the Coastal Plain League. He was promoted to the Piedmont League in 1942.

In a Richmond Times-Dispatch article from that summer (June 14), he recounted his experiences facing Cobb, Ruth, Sam Crawford and Joe Jackson. Bagby recalled that he and catcher Steve O’Neill worked seamlessly together, seldom differing on what pitch to throw, and that lefthanders simply could not hit his famed fadeaway pitch. Bagby fed Ruth a diet of these almost exclusively, learning his lesson early on after Babe slammed a curve off the League Park wall. He said, “The Babe got so mad at me once he bellowed, ‘Damn, if I won’t knock that ball down your throat sometime.’ ” Ruth never followed through on this, but he apparently learned how to hit this ephemeral menace. In limited matchups, mostly after 1920, when Bagby was past his peak, Babe rocked him for a .333 batting average, slugging three doubles, two triples and three home runs and walking 12 times in 42 plate appearances. Bagby, in his turn, went one for two against the pitching Babe.

Jim named Shoeless Joe Jackson the best hitter he had faced: “I don’t mean now that he had the finest average, but he hit the ball better. If Joe was as fast as Cobb he could have outhit Ty 40 to 70 points a season. Why, he never beat out more than five infield hits a season. When he hit the ball it was really hit.” Cobb, however, left his mark on Bagby’s record, tattooing him for a .398 average (47/118 in Bak, p. 52).

Bagby said he delighted in facing the top hitters: “It’s a funny thing, but my record shows the really great hitters never damaged me nearly as much as some of the ordinary batters.” The record may show otherwise. Bagby was generally more cautious with the stars than the ordinary hackers, and made a study of batters and would remember what worked and what did not.

Not long after this article appeared, Bagby suffered a debilitating stroke and resigned from the Piedmont League. Eventually he recovered enough to work for the Atlanta department stores J.M. High Co. and Davidson’s.

Jim Bagby Sr. died of another stroke in Marietta, Georgia, where he had lived for several years, on July 28, 1954.

After his death, Bagby’s widow, Mabel, a diabetic who had undergone two amputations, had her own brush with fame. Football star Elroy “Crazy Legs” Hirsch played on her behalf on the television game show “Strike it Rich” (Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, 1/29/55). Mabel had written the show asking for help so she could buy a better wheelchair and a sewing machine. “Crazy Legs” won $300 for her. The Cleveland Indians chipped in another $100, and an Atlanta clothing company added $250. An Atlanta firm donated a portable sewing machine.

Jim and Mabel had two daughters and a son, Jim Jr., who carried on his father’s Cleveland legacy as a two-time All-Star pitcher for the Indians. The Bagbys became the first father and son to pitch in the World Series when Jim Jr. appeared for the 1946 Red Sox.

Sources

Bagby’s Sporting News file.

Bagby’s Hall of Fame file.

Bak, Richard. Ty Cobb: His Tumultuous Life and Times. (Dallas: Taylor, 1994)

Phillips, John. Cleveland Baseball: Who Was Who in 1911-19. (Cabin John, Maryland: Capital, 1990)

Phillips, John. The 1918 Cleveland Indians. (Perry, Georgia: Capital, 1997)

Phillips, John. The 1920 Cleveland Indians. (Cabin John, Maryland: Capital, 1989)

Skipper, James K., Jr. Baseball Nicknames. (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1992)

Sowell, Mike. The Pitch That Killed. (New York: Macmillan, 1989)

Full Name

James Charles Jacob Bagby

Born

October 5, 1889 at Barnett, GA (USA)

Died

July 28, 1954 at Marietta, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.