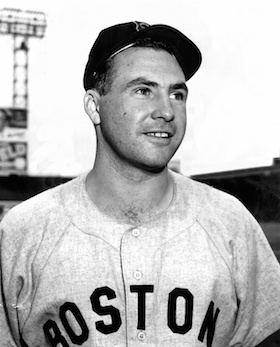

Jim McDonald

Right-hander Jimmie LeRoy “Hot Rod” McDonald was undefeated (1-0) as a pitcher for the team that first signed him. He won the only postseason game he ever pitched, Game Five of the 1953 World Series. He had a successful baseball career that ran from 1945 to 1960.

Right-hander Jimmie LeRoy “Hot Rod” McDonald was undefeated (1-0) as a pitcher for the team that first signed him. He won the only postseason game he ever pitched, Game Five of the 1953 World Series. He had a successful baseball career that ran from 1945 to 1960.

McDonald was born in Grants Pass, Oregon, on May 17, 1927. His parents came from different states. Mother Ruth (Wimer) McDonald was a Coloradan; father Lloyd McDonald was a Texan. Jimmie was his given name; he reported that his nickname was “Jim” but that “after several years of telling people Jimmie, I gave up.”1 He was of Irish-Dutch heritage. The McDonalds moved to California when Jimmie was young and he attended grammar school in San Jose and both junior high and high school in Modesto. His father worked as an automotive salesman. Nine years after Jimmie’s birth, he was joined in the family by a brother, Robert. Had he not gone into baseball, McDonald said he would have gone into the auto parts business.2

Jimmie was a talented baseball player in high school, and also played football and basketball. He pitched Modesto’s American Legion junior baseball team into the state finals. A halfback on the football team, he was named Central California’s most outstanding athlete in the fall of 1944.3 He was scouted by Brooklyn’s Charlie Wallgren in 1943 and was asked to sign, but he wanted to finish high school first. By the time Jimmie graduated, Wallgren had become a scout for the Boston Red Sox. McDonald explained, “When he went to work for Boston he looked me up and offered me a better deal than the other clubs did, so I signed a Louisville contract and went to spring training with them in ’45.”4

The Red Sox organization placed him with Class-A Scranton in 1945 and McDonald was 7-3 with a 2.45 earned run average. He’d apparently survived a baptism of fire in his debut. He said, “First professional game I ever pitched (9 innings), I had the bases full 7 out of 9 innings.”5

He was dropped down a class in 1946, placed with the Class-B Lynn (Massachusetts) Red Sox. There he was 6-3, but with a less-impressive 5.47 ERA. It was back to Scranton in 1947 and 1948, where he pitched very well again, with ERAs of 3.55 and 2.47 (and records of 10-8 and 13-4.)

The 20-year-old McDonald was upstaged in 1947 by 18-year-old Mickey McDermott (12-4, 2.86). In 1948, McDonald went the distance in a 17-inning game on August 30, a 4-3 win over Albany, Jimmy Piersall driving in the winning run. The Scranton Miners won the Eastern League pennant in 1948.

McDonald was placed with Double-A Birmingham in 1949 and had another very good year, 16-9, with a 3.15 ERA helped by back-to-back shutouts in May. In 1950, he was invited to spring training in Sarasota with the Red Sox, and promoted to Triple-A where he pitched for the Louisville Colonels.

As the season progressed, the Red Sox brought him up to Boston on July 23, sending pitcher Gordie Mueller down to Louisville. McDonald already had 11 wins to his credit, and had pitched a three-hit, 1-0, shutout on the 22nd.

McDonald’s big-league debut came in Detroit on July 27, 1950. Ellis Kinder had started for Boston and was touched for five runs through five innings. McDonald pitched the sixth and seventh without giving up a hit. He was taken out for a pinch-hitter in the top of the eighth. The Tigers won the game, 5-1. A few days later, McDonald confided, “I’ve found out that no matter what you tackle, there’s no easy way to make it. That’s why I probably gave the impression I was as cool as an iceman’s free list when I made my debut against the Tigers in Detroit. Actually I was scared to death. But one of Mike’s [Mike Ryba, Louisville Colonels manager] baseball proverbs is: Never let the other fellow know you’re scared; he might take advantage of it.”6

McDonald was 5-feet-10 and listed at 185 pounds. In 1950 and 1951, McDonald was a switch-hitter at the plate. “I was until told to hit right handed only,” he wrote Cliff Kachline.7

He appeared in eight more games for the Red Sox in 1950, all in relief. His only decision was a win on August 2 in Sportsman’s Park against the St. Louis Browns. McDermott had started the game, and the score was 8-6 in favor of the Browns after six innings. McDonald pitched two innings, giving up just one hit and walking one. He was the pitcher of record when the Red Sox scored three runs in the top of the ninth and held on to win the game, 9-8. McDonald worked 19 innings, with a 3.79 earned run average to go with his 1-0 record.

He had married Carmen Stegman several years earlier and the couple had two sons, Albert and Michael.

Some saw good things for McDonald in 1951. Jack Barry of the Boston Globe wrote that he “might be No. 1 rookie right now.” In the same article, Jimmy Piersall was quoted as calling McDonald “the greatest fielding pitcher I ever saw.”8 He trained with Boston again in 1951, but on April 2 was sent back to Louisville. He wasn’t happy about it and asked manager Steve O’Neill to send him to a Pacific Coast League team, where he would at least be closer to home. That wasn’t in the cards, and McDonald reported to Louisville, where he was 10-7 (3.50). On May 17 the Red Sox traded for Les Moss of the Browns, sending Matt Batts and Jim Suchecki (along with $100,000) and the promise of a played to be named later. The PTBNL was McDonald, sent to St. Louis on July 18.

The move brought him back to the big leagues and gave him the chance to start his first game. With no run support, the three runs the Washington Senators scored off him on July 27 was enough to win the game (it ended a 7-0 shutout.) On August 3 he balanced the scale with a 10-2 complete-game victory over the New York Yankees at Yankee Stadium. He then lost back-to-back complete games, the Browns only scoring once in each game, and beat the Yankees again, 4-3, on September 11. The Red Sox couldn’t have been pleased when he held them to three hits on August 21. His major-league record was 4-7 (4.07) in 1951, but the Yankees liked what they’d seen of him and dealt rookie catcher Clint Courtney to St. Louis for him on November 23.

For the next three seasons, McDonald worked both as a starter (33 games) and as a reliever (36 games) for the Yankees. Again, much had been expected of him before spring training began. John Drebinger of the New York Times said he might be the “sleeper” in the camp at St. Petersburg.9

He was used much more in relief in 1952, 21 times against just five starts, producing a 3.50 ERA and a disappointing 3-4 record. He would have pitched more but for an infected finger he suffered during spring training, which set him back and seemed to keep him out of sync. Nineteen of his 27 earned runs surrendered came in his five starts. In 1953, he started in 18 of 27 games and won half of them, finishing 9-7 (3.82).

The Yankees hadn’t used him in the World Series in 1952. But he was named the starter for Game Five in 1953.10 The Series was tied, two wins apiece for the Yankees and Dodgers. Game Five was at Ebbets Field. McDonald worked 7 2/3 innings, comforted by the five runs the Yankees scored in the top of the third. He gave up two runs through seven full, but tired rapidly in the eighth, giving up four runs (a three-run homer by Billy Cox finally prompted Yankees skipper Casey Stengel to call on his bullpen.) He was credited with the Yankees’ 11-7 win. “McDonald pitched a fine game until he tired,” Stengel said postgame. “And he fielded good – he really saved us trouble by getting over to first base a couple of times. He did a good job.”11 He did indeed register two putouts, and he was 1-for-4 at the plate, with a double driving in Phil Rizzuto in the top of the seventh.

He was asked to write a column for United Press, telling about the game. “Before the game,” he wrote, “I promised myself I’d win this one if I never did anything else in my life.”12 He admitted he’d tired and that was what did him in.

His most successful year was 1954, when he started 10 of 16 games, 4-1 (3.17). His best effort of the year was his first, a one-hit shutout of the Red Sox on Patriot’s Day in Boston. The one hit was a second-inning “handle hit” off the bat of Harry Agganis.13 But a groin injury on July 2 cost McDonald all the second half of 1954, save for a third of an inning in September.

The Yankees finished in second place in 1954, behind the Cleveland Indians. In November 1954, McDonald was traded away, part of one of the more complicated trades in baseball history, a 17-player deal with the Baltimore Orioles which included eight players to be named later, four from each team.14 Yet he was back with the Yankees organization before July 1955 was done.

Through July, McDonald was 3-4 for the Orioles with a poor 7.14 ERA. On the 30th of the month, the O’s bought Eddie Lopat from the Yankees on waivers, making room on the New York roster for Don Larsen. In a separate deal, the Orioles sold McDonald to the Denver Bears.15

He pitched in five games in Denver. Two months after the season, he and a friend took off in a private plane to fly to Miami, but the plane went missing over the Everglades and never arrived. Search planes were sent out the following day, but the search was called off after he “telephoned his wife that a flat tire on his plane had grounded him in an isolated camp overnight.”16 In the morning, they repaired the tire and flew to Clewiston.

He finally got to play on the West Coast, for Vancouver, for the first half of the 1956 season. On July 8, the Chicago White Sox bought his contract (he was 4-5 at the time) from Vancouver. McDonald pitched for the White Sox in 1956, 1957, and 1958, but he didn’t win a game. In 1956 he was 0-2 with an 8.68 ERA – not what the White Sox had been hoping for. There were mitigating factors in the first loss; Mel Parnell no-hit the White Sox at Fenway Park on July 14. The other one was also a loss to the Red Sox, at Comiskey. McDonald started, but gave up four runs in the top of the second inning, recording only one out that frame (and that a sacrifice fly.)

He opened the 1957 season in Chicago, but when the minor-league season began, he was optioned to Indianapolis (9-4, 2.98), returning in September. In all, he pitched 22 1/3 innings for the White Sox with an excellent ERA of 2.01. He lost his only decision, in relief. In 1958 he was 9-11 (3.46) with Indianapolis after appearing in three April games for the White Sox, his last in the big leagues. He gave up eight runs (five earned) in just 2 1/3 innings.

McDonald soldiered on, with another season in Indianapolis (10-11, 3.75) and then a 1960 season split between Miami and Charleston.

After baseball, McDonald owned and operated Lane’s Marine Sales and Service in Downey, California.

He died on October 23, 2004, in Kingman, Arizona.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed McDonald’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 McDonald player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame. The note about giving up was written in response to a February 19, 1974 letter to McDonald from the Hall of Fame asking him about his true first name. The “Hot Rod” moniker was because McDonald was “a hot rod driver by avocation.” John Drohan, “Red Sox Hit Road with Pitching Set,” Boston Traveler, July 24, 1950: 26.

2 American League questionnaire, in McDonald’s Hall of Fame player file.

3 Associated Press, “Modesto Hurler, 17, Signs with Boston,” Sacramento Bee, March 19, 1945: 17.

4 Handwritten note in McDonald’s Hall of Fame player file.

5 American League questionnaire, in McDonald’s Hall of Fame player file.

6 John Drohan, ‘M’Donald Serious About Game,” Boston Traveler, August 3, 1950: 11.

7 Handwritten note on the February 1974 letter to McDonald.

8 Jack Barry, “Jim M’Donald No. 1 Rookie for Red Sox?” Boston Globe, February 28, 1951: 17.

9 John Drebinger, “M’Donald, Young Pitcher, Hailed As ‘Sleeper’ Stat of Yanks Camp,” New York Times, February 26, 1952: 32.

10 See, for instance, Associated Press, “McDonald Hurls Today for Yankees,” Washington Post, October 4, 1953: C1.

11 Leonard Koppett, “Meyer Bemoans Yankee Power –Champs Confident,” Boston Globe, October 5, 1953: 5.

12 Jim McDonald, “McDonald Would Have Given Anything To Finish Game,” Charleston News and Courier, October 5, 1953: 6.

13 Hy Hurwitz, “Sox Split With Yankees; Agganis Ruins No-Hitter,” Boston Globe, April 20, 1954: 1.

14 Retrosheet explains: On November 17, 1954, McDonald was traded by the New York Yankees with players to be named later, Harry Byrd, Willy Miranda, Hal Smith, Gus Triandos and Gene Woodling to the Baltimore Orioles for players to be named later, Billy Hunter, Don Larsen and Bob Turley. The New York Yankees sent Bill Miller (December 1, 1954), Kal Segrist (December 1, 1954), Don Leppert (December 1, 1954) and Theodore Del Guercio (minors) (December 1, 1954) to the Baltimore Orioles to complete the trade. The Baltimore Orioles sent Mike Blyzka (December 1, 1954), Darrell Johnson (December 1, 1954), Jim Fridley (December 1, 1954) and Dick Kryhoski (December 1, 1954) to the New York Yankees to complete the trade.

15 “Lopat of Yankees Goes to Orioles,” New York Times, July 31, 1955: S3. Denver was a Yankees farm club.

16 United Press, “Pitcher McDonald Safe, Flat Tire Grounds Plane,” New York World-Telegram, December 6, 1955.

Full Name

Jimmie LeRoy McDonald

Born

May 17, 1927 at Grants Pass, OR (USA)

Died

October 23, 2004 at Kingman, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.