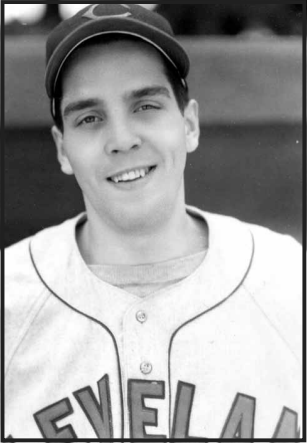

Jim McDonnell

Jim McDonnell, a backup catcher for the Cleveland Indians who got into 50 games from 1943 through 1945, left Organized Baseball after one season (1948) as a minor-league manager, and then figuratively disappeared. Though there is a file on him at the Baseball Hall of Fame, his post-baseball activities are uncharted.

Jim McDonnell, a backup catcher for the Cleveland Indians who got into 50 games from 1943 through 1945, left Organized Baseball after one season (1948) as a minor-league manager, and then figuratively disappeared. Though there is a file on him at the Baseball Hall of Fame, his post-baseball activities are uncharted.

James William “Mack” McDonnell was born on August 15, 1922 in the village of Gagetown, in Michigan’s “thumb” area. He was the third of five children born to James E. and Beatrice McDonnell. The 1920 US Census listed James E. as a farm laborer, living on his father’s farm. By the time of the 1930 US Census James E. had remarried and was living in a rented home in southwestern metropolitan Detroit, and was employed as a millwright in an automotive plant. He and his second wife, Margaret, had three children, born in the 1930s. At the time of the 1940 US Census, the family owned a home on Seymour Street in the present-day Burbank Neighborhood in far northeastern Detroit. James attended St. Edward’s Parochial School and Denby High School. In his Baseball Hall of Fame player questionnaire he listed basketball as his second favorite sport growing up.1

There is also not a lot of information about McDonnell’s early playing days, but he learned to play baseball in Detroit’s sandlot programs. To most of us, the word “sandlot” brings up images of vacant urban lots where unorganized games were played. However, the Detroit Amateur Baseball Federation ran a well-organized sandlot baseball program, consisting of competition in multiple age groups and classifications, and in venues all over the city. Northwestern Field was the number one site, where all the top players hoped to play. Richard Bak, author of several books about Detroit and Detroit sports, wrote that “Organized league games were played on Northwestern’s six diamonds from morning to night, with Detroit’s three daily newspapers carrying news and boxscores of the most important contests. . . . The caliber of play was top-notch, and the diamonds were kept in tip-top shape.”2

Jim played two years on the Roose-Vanker Post 286 American Junior Legion baseball team in Detroit. He was an outfielder on the Detroit team that won the Northeast Section Championship in 1938. The team included future Hall of Fame pitcher Hal Newhouser, who shut out the Legion team from San Diego in the first game of the semifinals, 4–0, but lost 2–1 on two unearned runs in the best-of-three final game.3 McDonnell played catcher on the 1939 Roose-Vanker team,who repeated as Michigan state champions, but lost in the Regional playoffs.

McDonnell was still in high school when he started playing professional baseball. That was in 1940, and due in large part to legendary Cleveland Indians scout Cy Slapnicka, who outbid eight other teams, including the Detroit Tigers, to grab McDonnell. “Slapnicka was a good talker,” McDonnell told Cleveland News columnist Ed McAuley in a 1944 interview.4

“Nine big league teams were after me. I turned down a good offer from the St. Louis Cardinals. I didn’t want to get into their chain gang. The thing finally came down to a choice between Detroit and Cleveland. Naturally, I leaned toward Detroit, but Slapnicka pointed out that the Tigers had Birdie Tebbetts, a young fellow already recognized as one of the best in the business, and behind him they had Ed Parsons. It looked as if I’d never get a chance to break in the Tigers.” The Indians, Slap told McDonnell, had Rollie Hemsley and Frankie Pytlak, both of whom had passed their peak. He predicted that in five years McDonnell would be wearing a Cleveland uniform. “Well,” Jim laughed during the 1944 interview, “the five years are up —and I’m a wearing a Cleveland uniform, all right. I certainly hope I can keep it.”5

At 6 feet tall and maxing out the scales at his top weight of 165 pounds, McDonnell was not your typical major-league catcher. He didn’t consider his lack of weight a handicap, but knew that logically his managers would like to see him bulk up some. Tony Lazzeri, the former Yankee infielder and future Hall of Famer, was McDonnell’s manager at Wilkes-Barre of the Eastern League in 1943. Lazzeri had him drink red wine before his meals in an attempt to put on weight.6

During his apprenticeship, McDonnell played with Fargo-Moorhead in the Class-D Northern League. He made his first appearance on August 9, 1940 and played in 28 games, hitting for a .302 average, though with only one extra-base hit, a double. It was a very young team; once McDonnell took over as catcher for the injured Chet Bujace, the average age of the starting lineup was just 19 years old.

In 1941 McDonnell was assigned to Appleton in the Class-D Wisconsin State League, and played in 105 games. He hit .310, with 26 doubles, six triples, and one home run. Appleton Post-Crescent sportswriter Gordon McIntyre wrote that “there’s not a better ‘clutch’ hitter”7 while describing McDonnell’s game-tying double in an August 15 game against La Crosse. Furthermore, the Post-Crescent’s Dick Davis claimed that “James McDonnell turned out to be the best defensive catcher [in the league] . . . .”8

The following year, he advanced to Class B, catching for the Cedar Rapids in the Three-I (Illinois-Indiana-Iowa) League. It wasn’t that strong a season for Mack; he played in only 47 games and batted .246. He primarily backed up six-year minor-league veteran Lou Kahn at catcher.

Why did Cleveland park a young prospect with a season-and-a-half of Class-D experience on a Class B team bench instead of assigning him to one of its two Class-C teams? Shortstop August Gregory and outfielder Pat Seerey made the jump from Appleton to Cedar Rapids with McDonnell, but they were regular starters at Cedar Rapids. A possible explanation is that Cleveland already had two good catching prospects slated for Class C. They apparently had decided to keep 20-year-old Ralph Weigel at Charleston, West Virginia for a second year in the Middle Atlantic League, and had assigned 18-year-old California high school sensation Ray Boone to Wausau, Wisconsin of the now Class-C Northern League. (Boone later converted to the infield and had a 13-year major-league career. His son Bob and grandsons Aaron and Bret were also major leaguers.)

Another explanation might have been McDonnell’s physical condition. McDonnell was moved to the Indians’ Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania team in the Class-A Eastern League in 1943, and it is there where the first print mention was found regarding his knee injury — “Because he had a cartilage removed from his left knee, following a severe injury, Jim McDonnell, Wilkes-Barre receiver, has been classified 4-F in the draft,”9 read a note in The Sporting News. But, in his March 15, 1944 interview, Ed McAuley wrote that McDonnell “has a broken knee cap and one leg is shorter than the other.”10 McDonnell told McAuley that he sustained the injury when he “blocked home plate one day in Fargo, N. D. He spent three weeks in the hospital and four months on crutches. . . . That was in 1940.”11 However, neither the Fargo Forum nor the Moorhead (Minnesota) Daily News mentioned the injury. The September 5 Forum mentioned that McDonnell had been hit on the knee by a foul tip, but he resumed playing after a short timeout and caught the remainder of the team’s games, including the season finale on September 9. It’s possible that McAuley misinterpreted McDonnell’s statements during an interview that took place years after the injury, or that McDonnell simply misspoke.

Furthermore the Appleton Post-Crescent did not mention a prior injury in its coverage of the 1941 Wisconsin State League team, nor did the Cedar Rapids Gazette in 1942. However, there was a description of an injury —or illness — that appeared in a pre-playoff article in the September 5, 1941 Post-Crescent stating that “McDonnell, regular catcher who has been ailing, was up and around yesterday and probably will be in uniform.”12 No further explanation was provided, but outfielder Joe Tipton caught the first playoff game on September 5. (He’d caught in eight games during the season, and made it to the major leagues in 1948 after converting to catcher.) McDonnell did not play in the game. The rest of the playoffs were cancelled by the teams because of the costs of retaining rosters in the face of continued rain postponements, so we don’t know if McDonnell could have played in subsequent games. If he had not been seriously injured, it would have been strange if the team hadn’t used its .310 clutch hitter. He’d played five games in the outfield during the season in games where Tipton gave him a breather, and he could have played there in the playoffs to get his bat in the lineup if his ailment was minor.

Thus, from our vantage point decades later it is unclear if McDonnell’s injury was a broken kneecap or torn cartilage, or exactly when the injury occurred. What we do know for sure was that McDonnell was 4-F when he showed up for spring training with the Wilkes-Barre Barons, Cleveland’s Class-A farm team. It was not as big a promotion as it might appear. The year 1943 represented the nadir for World War II minor league baseball. The total number of teams dropped from 214 in 1942 to 66 in 1943 —compared to 306 teams in 1940. Cleveland dropped from eight farm teams in 1942 to three —Baltimore in the Class-AA International League, Wilkes-Barre, and Batavia, New York in the Class-D PONY (Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York) League.

McDonnell had a strong year at Wilkes-Barre, with a .293 average in 104 games. After the Eastern League season ended, the Indians called him up on September 19.

McDonnell reported to manager Lou Boudreau and saw duty in two games. He debuted in Boston in the first game of a September 23 doubleheader. There was nothing riding on the game for either club, and the Indians were losing to the Red Sox 9–1 when Boudreau gave catcher Buddy Rosar a break and McDonnell an opportunity. He came in to catch the bottom of the eighth. Boston scored four more runs to make it 13–1. McDonnell led off the ninth inning with a walk and came around to score the first of six runs Cleveland put on the board in the top of the ninth. He came up a second time in the inning, but struck out. The Indians lost, 13–7. McDonnell played in Yankee Stadium in his other game, on September 27. He walked in his only plate appearance. The Yankees won that one, 5–2.

Cleveland only had 16 players under contract when spring training got underway in early March, 1944. Several players with 2-B draft deferments (War Industry Occupation) were among the unsigned. Some teams hoped that 2-B players could get six months’ leaves of absence to play during the season, and then return to their war plant jobs. However, Dan Daniel, New York World-Telegram columnist and TSN contributor, pointed out that “Draft Boards have told some players that the day they go from plant to diamond they are in Class 1-A and subject to immediate call by the Army.”13

Buddy Rosar, Cleveland’s 1943 All-Star catcher, was among the 2-B players who were waiting to make up their minds about signing. He was working in a defense plant in Buffalo. Without Rosar, McDonnell was the only catcher in camp when spring training began. Jim Devlin, McDonnell’s backup in 1943 at Wilkes-Barre and also 4-F, was invited but had not signed a contract. Devlin finally signed in late March, and the Indians also signed 30-year-old Russ Lyon, a former minor-league catcher who had been playing semipro ball for the past four years. Lou Boudreau, Cleveland’s 26-year-old player-manager, preferred to have an experienced starting catcher to handle pitchers, but Ed McAuley reported that “The Boy manager notes with satisfaction that Jim McDonnell, the 4-F youngster from Wilkes-Barre, handles the receiving duties in workmanlike fashion. . . .”14 Just to be on the safe side, Boudreau had the Indians reactivate thirty-six-year-old coach George Susce, who had been a part-time catcher for five different teams in seven years in the big leagues.

McDonnell was the choice as Cleveland’s catcher by default, but showed well enough in spring training (“a better catcher than the Indians expected to have”15) to open the 1944 season with the club.

McDonnell was the opening-day starter on April 19 at Chicago. He batted 2-for-4 and scored the Indians’ only run in a 3–1 loss to the White Sox. He started two of the next four games, giving way to Lyon and Devlin on the other two. But, with the team at 1–5, Boudreau decided to give the starting job to George Susce on April 28. “Boudreau said he had no complaint against the work of Jim McDonnell, Russ Lyon and Jim Devlin, the newcomers to the catching corps,” Ed McAuley wrote, “but that, since the team had been losing, he thought a more experienced sign-flasher might be of some assistance to the pitchers.”16

Susce caught eight consecutive games, and then the Indians were cheered by the news that Buddy Rosar had arranged a transfer, with his draft board’s approval, to a war-production job at the Weatherhead Company in Cleveland, and would be able to arrange his working hours to play weekday home games, and weekend road games as long as transportation could be obtained to get him back to his job on Monday. This was made possible by a ruling from Commissioner Landis’ office, through his secretary, Leslie O’Conner, who wrote: “The use of part-time players in major league games would violate no rule of baseball.”17 The letter was in response to a request from New York World-Telegram sportswriter Dan Daniel, asking for clarification. Yankees president Ed Barrow, among others, had opposed the use of part-time players, claiming that it required a permit from Commissioner Landis, and doubted that Landis would approve. There was still some risk for the 2-B players after the ruling, since local draft boards were not bound by Landis’ opinion, but at least the major-league teams now would not stand in the way of players’ negotiations with their local draft boards.

Rosar started his first game on May 6, and managed to catch in 99 of the team’s 141 remaining games. McDonnell started only six more games after Rosar arrived, and in late July was optioned to the Red Sox’ Louisville club in the American Association. He played in 14 games with Louisville and was called back to Cleveland in September, but did not play. For the season with the Indians, McDonnell had played in 20 games and was 10-for-43 (.233) with four RBIs, all on the road. But he made five errors in 50 chances, for a fielding percentage of .900. McDonnell did play in another game for the Indians in 1944, a July 10 exhibition against the Sampson Naval Training Station in New York —and he played shortstop.)

The Indians’ catching situation in 1945 spring training appeared to be a repeat of 1944 — Buddy Rosar, back at his prior war production job in Buffalo, was taking a wait-and-see attitude about signing his contract, and McDonnell was the again the favorite to be the opening-day starter.

As training camps opened, the status of part time players with 2-B War Industry Occupation deferments was unclear, and players with 4-F deferments were also being challenged. War Mobilization Director James F. Byrnes shook up the major leagues with his letter to Selective Service Director Major General Lewis Hershey on December 9, 1944. “I am seriously concerned that at this critical period, when we are exerting every effort to direct manpower into critical war industries, we find such a number of men between the ages of 18 and 26 engaged in professional athletics of all types,” Byrnes wrote.18

Furthermore, Byrnes suggested new legislation to give the War Manpower Commission power to establish new controls over the four million men classified 4-F. “At a press conference he stated that a restudy of those now found physically disqualified for military service might result in their placement in combat duty, limited military service or in war production unless they were already working in essential activity.”19 President Roosevelt, in his January 6 State of the Union Address, also called for passage of a “work-or-fight” order.20 This could have been devastating to baseball — with 225 of 541 players on major-league spring training rosters listed as 4-F.21 But the legislation was never passed.

Subsequently, however, to ensure that uniform standards were applied throughout the nation, local draft boards were required to refer all proposed 4-F classifications for professional athletes to the War Department for review and final approval. “In some baseball quarters,” Dan Daniel wrote, “there is a disposition to regard some of the cases as discrimination against professional athletes, but friends of baseball here [Washington D.C.], including Representative Jennings Randolph of West Virginia, warn the major leagues strongly against raising any such cry.”22

(Illinois Congressman Charles Melvin Price later filed a formal protest against the apparent discrimination to Undersecretary of War Robert Patterson.)

Director Byrnes also ruled that “any deferred worker who changes his job without his draft board’s permission is to be inducted immediately. The Army is waiving its physical requirements in such cases.”23 With all this uncertainty, it is understandable that Buddy Rosar was a no-show when spring training began on March 12 in Lafayette, Indiana. Only one-half of the roster reported the first day. Among the absentees was player-manager Lou Boudreau. Although he was rated 4-F in 1944, he had not been called for re-examination since the new War Department rules had been established. He was working in the offseason as a personnel assistant in a Harvey, Illinois war plant. “In my opinion,” said Boudreau, “the players won’t leave their war jobs unless they have specific assurances that they’ll be allowed to play ball; that they won’t be forced into some kind of factory work less desirable than the kind they are doing at present.”24

War Manpower Commission chairman Paul McNutt partially cleared up the situation on March 21 when he ruled that players with 4-F deferments could leave their offseason jobs to play baseball without triggering an immediate reclassification to 1-A. This appeared to permit Boudreau to report to spring training, but left players with 2-B war production deferments —like Rosar —on their own to negotiate with their local draft boards. Some 4-F players had problems despite McNutt’s ruling. Boudreau’s local draft board later reclassified him 1-A for leaving his war occupation job, but he was not subsequently inducted.

In early April 1945, manager Boudreau indicated that McDonnell would be his choice for starting catcher. “I’ve always been confident I could catch 100 games or better for the Indians,” McDonnell said. “Everyone has been worrying about my weight, although I’ve tried to make it clear that I never vary more than a pound or two.”25 The Cleveland Plain Dealer said the pitchers had confidence in his game-calling.

At the beginning of the season no catcher had been named the starter for Opening Day; but McDonnell was the assumed starter. This was his season to prove that despite his small stature he had the durability to complete a major-league season behind the plate. The Indians also had George Susce, a veteran catcher-coach, and 19-year-old Henry Ruszkowski, an impressive sandlot product out of Cleveland who had spent the previous year with Wilkes-Barre.26

McDonnell thought he had secured the first-string catching job. Ruszkowski, however, had different plans, and put in an impressive performance both at the plate and behind it, changing management’s mind and drawing the starts in a platoon against left-handed pitching. McDonnell’s hard-won tenure as a regular was one of the shortest-lived in history. Paul O’Dea pinch hit for him in just his third start of the season and stepped in once again in the next game.27 To make matters worse for McDonnell, on May 29 the Indians acquired catcher Frankie Hayes from Philadelphia for Rosar, who had been inactive to that point. Hayes, who was one of the top receivers in the American League, quickly took over the starting position and was one of the leaders among American League catchers with 151 games played (119 of them for Cleveland) and a .986 fielding percentage as he was named to the American League All-Star team.28 At the time of the trade Hayes had caught in 188 consecutive games, and was just 29 games from the major-league record of 217, and Lou Boudreau said he would be given an opportunity to set the mark. Hayes easily set the record, and extended it to 312 games before he sat out a game early in 1946.

McDonnell stuck with the Indians all through the 1945 season, batting .196 with eight RBIs. Interestingly enough, McDonnell’s first and last games with Cleveland came on September 23 two years apart. Between 1943 and 1945 he played in 50 games and had 95 at-bats with a batting average of .211. As a catcher, McDonnell amassed 126 putouts with a fielding percentage of .953. His percentage of runners caught stealing was just below the league average of 42 percent. “I think I know something about the mechanics of catching,” McDonnell said, “my arm isn’t the most accurate in the world, but for strength I’ll match it with anyone’s.”29

“I’ll never be a power hitter,” McDonnell admitted.30 His career slugging percentage was .232, which was just above his batting average, but below his on-base percentage of .272. His 20 career hits resulted in 22 total bases (18 singles and 2 doubles). His career strikeouts matched his career walks, with eight each.

Japan’s surrender on September 2 was a time of great joy and relief for the nation. Twelve million men were in uniform in September 1945, and the War Department forecast that there would be only two million left by September 1946. Baseball looked forward to getting back to normal, with no worries about draft notices and deferments, but it was a bittersweet time for the wartime “replacement” players. “Only a week or so ago,” Dan Daniel had written shortly after V-E Day, “the big worry in baseball was keeping the 4-F’s; now the worry shifts to players who may not be able to hold their jobs against bids from returning servicemen.”31 Catchers Hayes and McDonnell knew they would face daunting competition in 1946 from 25-year-old Jim Hegan, who had started a third of Cleveland’s games in 1942, and was returning from three years in military service. Sherman Lollar, 21, would also be in spring training camp. He had been the Class-AA International League MVP in 1945 when he hit .364, with 34 home runs and 111 RBIs.

According to his American League Questionnaire, if McDonnell had not played professional baseball, the trade or profession he would have planned to adopt was toolmaking. He had also done work as an insurance agent. McDonnell was also an avid skater and bowler.32 On December 8, 1945, he and Indians pitcher Steve Gromek took to the lanes and led the Western All-Stars to a defeat of the Eastern All-Stars by the score of 2,444 to 2,295. The event sold over $149,000 in War Bonds, and although McDonnell was the high bowler with a score of 516, Babe Ruth was the big draw while bowling 477 for the losing Eastern team.33

McDonnell never played in another major-league game. In January of 1946 the Indians sent McDonnell and a cash payment to San Diego of the Pacific Coast League for shortstop Charles Brewster.34 He played for the Padres in 1946 (69 games, batting .238) and 1947 (33 games, .242), both times in a backup role.

McDonnell had one stint managing, as the player-manager of Gloverstown-Johnstown in the Class-C Canadian-American League in 1948. The team finished sixth in the eight-team league, with a record of 68-69. McDonnell played in 85 games and hit .261.

McDonnell married Lee Miller on Valentine’s Day, February 14, 1942. She died on April 21, 1953, and he never remarried.35 At the time of the 1968 Hall of Fame player questionnaire, McDonnell said he had been an insurance agent, but was “unemployed while recuperating from a long illness and hospitalization.”36 He was still living in the old family home on Seymour St. in Detroit when he died on April 24, 1993.

Jim and Lee had a daughter, Carol Ann, born in 1943, who married Leonard Michaels and lived in West Bloomfield, Michigan, in 2014. The birth of a later son was reported in the May 21, 1944 Cleveland Plain Dealer.

A communication from a family member received by Ashlie Christian in August 2014 indicates that Jim McDonnell died estranged from his family.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the authors also accessed McDonnell’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, The Sporting News, and Baseball-Reference.com.

The following sources were also utilized in the preparation of this biography:

Jordan, David M., A Tiger in his Time: Hal Newhouser and the Burden of Wartime Ball (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1990).

Johnson, Lloyd and Miles Wolff, ed. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 1997).

Mead, William B., Even the Browns (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1978).

Charlotte Observer

Detroit Free Press

baseball-reference.com/

Edwin Denby Log (Edwin Denby High School, Detroit), January 1941, (classmates.com/yearbooks/).

retrosheet.org/

United States Federal Census: 1910, 1920, 1930, and 1940 (ancestrylibrary.com/).

United States Social Security Death Index (familysearch.org/pal).

Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan: Ann Arbor.

Harlan Hatcher Graduate Library, University of Michigan: Ann Arbor.

Notes

1 McDonnell player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

2 Richard Bak. “Northwestern Field in Detroit launched many great baseball careers,” (blog.detroitathletic.com/category/richard-bak/, accessed October 17, 2014).

3 Sam Miller. “Errors Fatal to Losing Pitcher,” Charlotte Observer, August 30, 1938, Sec 2, 4.

4 Ed McAuley. “Has a Visit With McDonnell, Tribe’s Catching Hope,” Cleveland News, March 15, 1944.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Gordon McIntyre. “Papers Beat LaCrosse; Dancisak Is Injured,” Appleton Post-Crescent, August 16, 1941, 12.

8 Dick Davis. “Appleton’s Third-Place Finish Offset by Individual Honors,” The Sporting News, November 27, 1941, 2.

9 “Eastern League,” The Sporting News, June 10, 1943, 12.

10 McAuley, “Has a Visit With McDonnell, Tribe’s Catching Hope.”

11 Ibid.

12 “Appleton Set For Opening Playoff Game,” Appleton Post-Crescent, September 5, 1941, 13.

13 Dan Daniel. “Players Being Classified 1-A When They Leave War Plants,” The Sporting News, March 2, 1944, 2.

14 Ed McAuley. “Vet With Mask, Big Tribe Task,” The Sporting News, April 6, 1944, 6.

15 Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 17, 1944.

16 Ed McAuley. “Rosar Raises Tribe’s Spirits as Part-Timer,” The Sporting News, May 4, 1944, 4.

17 Dan Daniel. “Use of Part-Time Players From War Plants Okayed,” The Sporting News, April 6, 1944, 2.

18 Edgar G. Brands. “4-F Edict Will Affect Third of Majors,” The Sporting News, December 28, 1944, 8.

19 Lewis Wood. “Put 4-F’s To Use, Byrnes Suggests: For Stronger WMC,” New York Times, January 2, 1945,1.

20 John H. Crider. “Roosevelt Demands a National Service Act . . . ,” New York Times, January 7, 1945, 1.

21 Shirley Povich. “Game to Ride Out New Blow, Capital Relief,” The Sporting News, January 11, 1945, 2.

22 Dan Daniel. “Their Dreams Are Getting Better All the Time,” The Sporting News, March 15, 1945, 2.

23 George Zielke. “Game Okayed by FDR in ‘Pinch-Hitter’ Form,” The Sporting News, March 22, 1945, 8.

24 Ed McAuley. “Green Grass Pretty, But It’s Green Light That Lou Wants,” The Sporting News, March 1, 1945, 4.

25 Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 6, 1945.

26 The Sporting News, April 5, 1945.

27 The Sporting News, May 17, 1945.

28 Baseball Digest, July 2001, 86.

29 McAuley, “Has a Visit With McDonnell, Tribe’s Catching Hope.”

30 Ibid.

31 Dan Daniel. “V-E Day Due to Ease Game’s Player Shortage,” The Sporting News, May 10, 1945, 1.

32 American League questionnaire, McDonnell player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

33 The Sporting News, December 13, 1945.

34 The Sporting News, January 31, 1946.

35 McDonnell player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

36 Ibid.

Full Name

James William McDonnell

Born

August 15, 1922 at Gagetown, MI (USA)

Died

April 24, 1993 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.