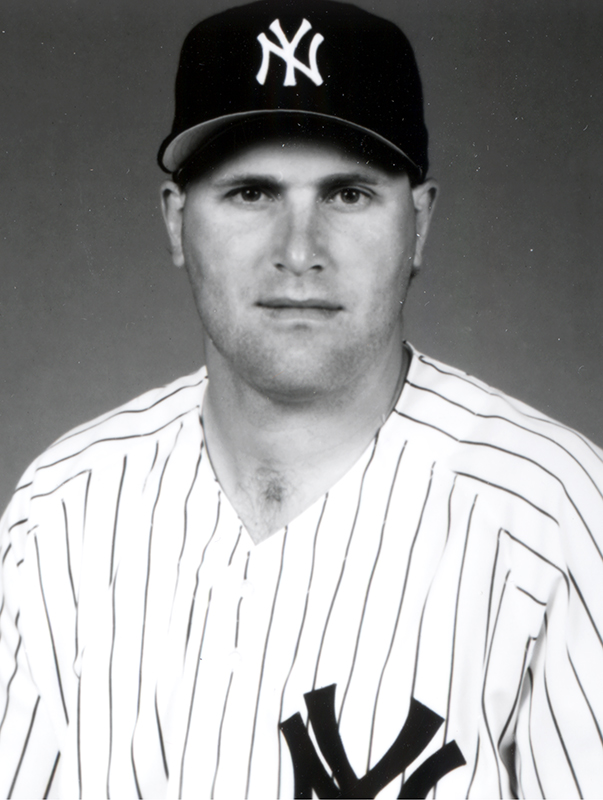

Jim Mecir

Jim Mecir pitched professionally for 15 years, from 1991 to 2005, including all or part of 11 seasons in the major leagues, with a permanent disability that would have kept most people on the sidelines. Mecir (pronounced Mah-sear) was born with a club foot, a condition that was only partially corrected by medical procedures in common use when he was an infant. He defied the opinions of doctors and coaches by successfully competing in sports at all levels, culminating with his successful career in major-league baseball as a top relief specialist.

Jim Mecir pitched professionally for 15 years, from 1991 to 2005, including all or part of 11 seasons in the major leagues, with a permanent disability that would have kept most people on the sidelines. Mecir (pronounced Mah-sear) was born with a club foot, a condition that was only partially corrected by medical procedures in common use when he was an infant. He defied the opinions of doctors and coaches by successfully competing in sports at all levels, culminating with his successful career in major-league baseball as a top relief specialist.

Club foot (also known as CTEV for Congenital Talipes Equinovarus) is a malformation of the bones, joints, muscles, and blood vessels in the foot caused by abnormal development of the fetus during pregnancy. In appearance a clubfoot is usually somewhat kidney shaped with a high mid-foot arch. The condition is characterized by the inward rotation of the back part of the foot at the ankle and the turning under of the forefoot. In addition, the heel is drawn up due to the strain on the Achilles tendon, resulting in an inability to bring the foot to a flat standing position.1

Club foot is a relatively common birth defect, occurring in approximately one out of 735 births. The affliction is ancient – Egyptian mummies have been discovered with club feet. The disfigurement occurs roughly twice as often in boys as in girls and affects both feet (bilateral clubfoot) about half the time. Although the condition appears to be genetic, it often seems to be repressed and can skip many generations. The severity of the condition varies widely. Several world-class athletes have been born with the deformity including Olympic figure skater Kristi Yamaguchi, Pro Bowl quarterback Troy Aikman, and women’s professional soccer star Mia Hamm. Former major-league infielder Freddy Sanchez was also born with a club foot.2

Thanks to advances in the treatment of club foot in the latter part of the twentieth century, most patients getting treatment in early infancy now recover completely during early childhood and are eventually able to walk and run normally. That was not Jim Mecir’s situation. When he was an infant an attempt was made to straighten his disfigured right foot and then by a surgical procedure involving the temporary insertion of a bar between his feet. Another operation at the age of 8 was required which left the calf muscle atrophied after the procedure, resulting in his right leg being an inch shorter than the left and causing him to walk with a pronounced limp.3

It has generally been reported that Mecir was born with two club feet, but in a recent telephone interview he disclosed that only his right foot was deformed – his left foot was normal.4

Despite his condition, Mecir developed into an outstanding high-school athlete playing basketball and even running track in addition to starring in baseball for East Smithtown (New York) High. When Mecir first joined the Oakland A’s during the 2000 season, his new teammate Jason Giambi, recalled playing with him in the 1994 Arizona Fall League. “I guarantee you he’s one of the fastest guys on this team,” Giambi stated. “He can fly.”5

James Mason Mecir was born on May 16, 1970 in Bayside, a neighborhood in the New York City borough of Queens. He grew up in Smithtown on Long Island. Long Island, of course, is Carl Yastrzemski territory and as an 18-year-old, Jim won the award bearing the Red Sox legend’s name that goes to the outstanding high-school baseball player in Suffolk County. Previous winners included major leaguers Tom Veryzer and Neal Heaton, and National Football League quarterback Boomer Esiason, while former major-league pitcher Bill Koch and infielder Tony Graffanino as well as current big leaguers Steven Matz and Marcus Stroman were subsequently honored.6

Scouting reports tabbed Mecir as a prospect worth following. He was described as intelligent with good stuff, a loose arm, and a strong upper body. His clubfoot and resulting limp were mentioned, but didn’t seem to be considered a major issue. Of some concern were his mechanics. A tendency to sling the ball, opening up too soon, and throwing with his arm only were the observations of at least two scouts, though they apparently did see a connection between these flaws in his delivery and his foot condition.7

After high school, Mecir attended Eckerd College, a small private school in St. Petersburg, Florida. Eckerd, a Division II school, was not exactly a baseball powerhouse, although two of its alumnae, Jim Lefebvre and Steve Balboni, had made the major leagues. The Eckerd pitching coach was former major leaguer Rich Folkers, who was initially dubious about Mecir’s ability to play with his condition, but was quickly impressed with Jim’s all-around athletic ability once he saw him in action. While at Eckerd, Mecir learned to throw a screwball by watching the left-handed Folkers work with a lefty teammate. The screwball is an unusual pitch that breaks in the opposite direction from the arm movement. The pitch requires pronating the arm so that the palm of the pitching hand actually ends up facing away from the body at the completion of the delivery. Not only is the pitch difficult to master, it’s also considered very hard on the arm and has largely fallen out of favor for that reason. In fact, according to the pitch tracking system PitchF/X, Hector Santiago of the Los Angeles Angels was the only pitcher to throw the pitch in the majors during the 2015 season. But the pitch has an illustrious history. Legendary right-hander Christy Mathewson threw it in the early years of the twentieth century, although it was called a fadeaway in those days. Probably the most renowned screwballer was former New York Giants left-hander Carl Hubbell, who used it almost exclusively to win 253 games from 1928 to 1943. Longtime Braves ace Warren Spahn won 363 National League games with the aid of the “scroogie.” Of more recent vintage is Fernando Valenzuela, who rode his screwball to Rookie of the Year and Cy Young Award honors in 1981. And of course there’s righty relief ace Mike Marshall, a master of the pitch and doctor of kinesiology (the scientific study of body movement). Marshall, who set all-time records by appearing in 106 games and pitching 208 innings in relief in 1974, maintains that the screwball motion is actually easier on the arm.8

Mecir, whose pitches had a natural tendency to tail away, struggled with traditional breaking pitches, but seemed to pick the screwball up quickly. With Folkers’s guidance and encouragement, he incorporated it into his arsenal to complement his fastball.

By his junior year Mecir was gaining attention as a big-league prospect. A 1991 preseason scouting report tabbed him as a “definite prospect” worth a bonus in the $50,000 range. The report mirrored previous ones in mentioning his strong, well-developed upper body, but also noted his “thinnish” legs. It predicted that he had the “stuff to be front-line ML starter.” As for his clubfoot, the report stated, “[He] walks with a slight limp,” then added, “no other effects.” The observation “will at times sling the ball” was again noted, but was dismissed as “correctible,” indicating that a link between Mecir’s physical disability and his resulting unorthodox pitching motion was still not recognized.9

In the third round of the 1991 amateur draft, Mecir was selected by the Seattle Mariners, foregoing his senior year at Eckerd, although he did go back to earn a degree in Economics. He began his professional career as a starting pitcher with San Bernardino in the California League that year. After three mediocre seasons as a starter, he switched to relief in 1994 with Jacksonville in the Southern League and enjoyed outstanding results. He posted an excellent 2.69 earned-run average along with 13 saves, signaling that his days as a starter were over. He never started another game except for a few short stints on minor-league rehab assignments. After another fine performance in relief for Tacoma of the Pacific Coast League in 1995, Mecir was called up to the Mariners for a late-season audition. His September 4 debut saw him pitch 3⅔ innings at Yankee Stadium, allowing only one unearned run. His only other appearance was on October 1, with one inning of scoreless ball in Texas against the Rangers.

That offseason, Mecir was traded to the New York Yankees along with first baseman Tino Martinez and reliever Jeff Nelson for pitcher Sterling Hitchcock and third baseman Russ Davis. He spent the 1996 and 1997 seasons bouncing between the Yankees and their Columbus International League affiliate, pitching well in the minors but failing to establish himself in the big time.

At the end of the 1997 campaign, Mecir was sent to the Boston Red Sox to complete an earlier deal. He caught a break six weeks later when he was selected by the newly formed Tampa Bay Devil Rays in the 1998 expansion draft. Finally getting an opportunity to pitch regularly, he won seven games while losing only two for a team that lost 99 times to finish with the worst record in the American League. He posted a fine 3.11 earned-run average, and struck out 77 batters in 84 innings. He got off to a great start in 1999, appearing in 17 of Tampa Bay’s first 33 games, but fractured his right elbow in a freak collision with a teammate shagging flies during pregame batting practice – ending his season prematurely.10

Mecir recovered from the broken elbow to win seven of nine decisions for the Devil Rays before being swapped to Oakland in July 2000 for fellow reliever Jesus Colome. Although it was exciting to move from a cellar-dwelling club to a contender, the Tampa Bay area had become Mecir’s adopted home. It’s where he attended college and where he’d met his wife, Pamela, a Tampa native. Jim was drafted by Tampa Bay while the couple was honeymooning and they’d set up housekeeping in nearby Gulfport. It was difficult to leave.11

But Mecir quickly became an integral part of the A’s bullpen corps, setting up for closer Jason Isringhausen. He even closed some games himself and racked up four saves when Isringhausen hit a rough spell. For the season, Mecir’s combined won-lost record for Tampa Bay and Oakland was 10 wins against 3 losses with a tidy 2.96 ERA to help the A’s make it to the Division Series as the wild-card entry. They lost to the Yankees, but Mecir was outstanding, pitching 5⅓ scoreless innings in three appearances, yielding only one hit.

Mecir also pitched well in 2001as the A’s again captured the wild-card berth. But the year was not without some disconcerting physical problems. His disfigured right leg started to give him trouble, and for the first time complications from his clubfoot put him on the disabled list.

Throughout his career, Mecir had steadfastly followed the universal mantra of athletes with disabilities – claiming that his condition didn’t really put him at a disadvantage. He had always stubbornly maintained that his limp was the sole manifestation of his disfigurement and that it affected only his walking. The reality, however, was that his whole pitching motion was unconventional because of his damaged foot. He wasn’t able to keep his left shoulder closed the way pitchers are generally taught. As the scouts noted when he was a prospect, his left shoulder would fly open when he delivered the ball and he was largely dependent on the torque generated from his upper body for velocity. What they failed to discern was that his weakened right leg made it impossible for him to properly drive off the mound. Of course, Mecir claimed that this actually helped him by making his pitches more difficult for the batter to pick up. In addition, he contended that his upper-body mechanics allowed him to throw his vaunted screwball more naturally.12

Inevitably Mecir had to accept the fact that his condition was having an adverse impact on his body. He is a big man, packing 230 pounds on a 6-foot-1 frame in his prime (according to his 2002 SI.com player page). Over the years the constant wear and tear, which was intensified by the misalignment of his right leg, destroyed the cartilage in his knee. Complicating the problem was that in addition to a club foot, Mecir was born without an anterior cruciate ligament. Consequently, with almost no cartilage left, the bone grinding on bone caused muscle problems as well.13

In August 2001 Mecir’s knee became so painfully inflamed that he had to undergo arthroscopic surgery. During the procedure, a jelly-like material harvested from the back of a rooster’s head was injected into the knee to lubricate the joint and rebuild the damaged meniscus or fibrous cartilage. Mecir made it back to the mound in early September and posted a sensational 1.46 earned-run average over his final 12 appearances. But he was not as effective in the Division Series; the A’s were again eliminated by the Yankees. For the entire regular season he posted a fine 3.43 ERA.14

This all played out against the backdrop of 9/11’s horrific occurrence that narrowly missed engulfing Mecir’s family. His father, James Sr., was a New York City firefighter. He and Jim’s mother, Carole were on vacation when the World Trade Center was attacked. Upon hearing of the catastrophe, he rushed to the site to help out. Several friends and co-workers were missing. “It’s definitely hard on him,” Jim said. “It’s not good there. Luckily, he was on vacation. My parents called me pretty quickly and told me they were fine.”15

Mecir’s 2002 season was similar to the previous campaign. He pitched well, but as the season wore on, his knee wore out. He ended up with a 6-4 won-lost mark in 61 games and ranked sixth in the league with 21 holds, but his ERA rose to 4.26 and his workload was greatly reduced in the closing months of the season because of soreness in his right knee. The damaged joint was simply making it impossible for him to plant his foot and deliver the ball with the same velocity he once had. In the past, his fastball approached the mid-90s, but now he struggled to reach the 90-mph mark.16

“There’s no question this could affect my career,” Mecir admitted in a Baseball Weekly column. “Over the years all the grinding has destroyed the cartilage and now I’m getting muscle problems. I’m just not throwing the way I felt I could before.”17

The A’s captured the 2002 division title outright, but they were once again eliminated in the first round, this time by the California Angels. Mecir pitched only a single scoreless inning in the Division Series.

Mecir’s leg problems were compounded when he injured his left knee in the offseason while playing with his children. In November he underwent surgery to repair a torn patella tendon and was expected to miss the first two months of the 2003 season.18

The veteran workhorse returned to the mound ahead of schedule, making his first appearance three weeks into the season. He may have rushed it as the 2003 campaign turned out to be the worst of his career. His ERA soared to an unsightly 5.59, although his FIP (Fielding Independent Pitching) indicated that he actually pitched somewhat better than that. Later in the season his balky knee sent him back to the disabled list. All told, he appeared in only 41 contests and pitched only 37 innings. The A’s finished first in the American League West again and were again eliminated in the first round. Mecir pitched only two-thirds of an inning in the five-game series loss to the Boston Red Sox.

One of the few bright spots of that difficult season occurred when Mecir was named the winner of the Tony Conigliaro Award, which goes annually to “the player who most effectively overcomes adversity to succeed in baseball.”19

The 2004 season was the final year of a four-year pact Mecir signed with Oakland. Considering his 2003 performance, his roster spot was in jeopardy, but he made the squad and rewarded the A’s with a workmanlike 3.59 ERA in 65 games – the most appearances he had made since 1998, despite starting the season on the disabled list – and ranked third in the league with 21 holds. But for the first time in Mecir’s tenure with Oakland, the club failed to make the postseason.

After the 2004 campaign the A’s cut ties with Mecir. He considered retirement, but eventually filed for free agency and signed with the Florida Marlins. Mecir pitched in 46 of the Marlins’ first 109 games with a fine ERA of 3.00, but the heavy workload took its toll on the 35-year-old hurler’s troublesome shoulder. He landed on the disabled list in early August and pitched only sparingly when he returned on September 4. For the year he appeared in 52 games and finished with a 3.12 ERA for a little over 43 innings of work. At the end of the season, he announced his retirement as a player.

Throughout his career Mecir’s affliction had garnered little attention, but in his final season it caused a bit of a flap. On Sunday, May 15, 2005, he endured his worst outing of the season. Entering the game in San Diego in the bottom of the seventh with the Marlins up 4-3, no outs, and the bases loaded, he yielded eight runs (five of which were charged to him) before finally retiring the Padres.

ESPN Baseball Tonight analyst John Kruk, noting Mecir’s limp when he took the mound and unaware of his deformity, criticized the Marlins on the air for bringing in an injured hurler. When advised of the pitcher’s condition, Kruk publicly apologized. Mecir did not take offense, quietly defusing the situation by shrugging it off.20

Mecir retired from baseball with a lifetime 29-35 won-lost record and an ERA of 3.77 for 527 innings of relief over 474 appearances. He boasted a sparkling 1.74 ERA for seven postseason appearances.

As of 2016 Mecir, his wife, Pamela, and their three children lived in the village of Kildeer, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. He worked as a motivational speaker, using his baseball experiences to teach communication and teamwork skills to businesses, and he kept his hand in baseball by providing private pitching instruction to youngsters. In 2016 he was inducted into the New York State Baseball Hall of Fame.21

In his heyday, Jim Mecir was considered one of the best set-up men in the game. A rare talent, with a screwball that made the right-hander as effective against lefty hitters as righties, thereby minimizing the need for additional pitching changes for lefty/righty match-ups when he was on the mound. He was also excellent at stranding baserunners.

While Mecir was with Tampa Bay, his pitching coach, Rick Williams, summed up the man and the pitcher with these words. “Courage is the first word that comes to mind. Guts … Perseverance … Not listening to anyone tell him what he could not do and proving that he can. … It’s just not a factor with him. It really isn’t a limitation. He’s turned it into a nonfactor.”22

Notes

1 “Facts About Clubfoot: Clubfoot Information and Parental Support,” Clubfoot Support Group, Seekonk, Massachusetts, xprss.com/clubfoot/credentials.asp (accessed 9/4/2002).

2 “Facts About Club Foot: Clubfoot Information and Parental Support”; Mayo Clinic Staff, “Clubfoot Overview,” Mayo Clinic, mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/clubfoot/home/ovc-20198067 (accessed 11/2016); “Famous People with Club Feet or Foot,” Disabled World, disabled-world.com/artman/publish/famous-clubfoot.shtml (accessed 11/2016).

3 “Facts About Club Foot: Clubfoot Information and Parental Support”; Susan Slusser, OO“Oakland’s New Reliever Has Overcome Skeptics,”n Francisco Chronicle, August 4, 2000, sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/2000/08/04/SP55783.DTL (accessed 3/2/2003). Susan Slusser, “Oakland’s New Reliever Has Overcome Skeptics,” San Francisco Chronicle, August 4, 2000, sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/2000/08/04/SP55783.DTL (accessed 3/2/2003).

4 Author telephone interview with Jim Mecir (12/7/2016)

5 Susan Slusser.

6 “Yastrzemski Award,” Newsday-High School Sports, newsday.com/sports/high-school/yastrzemski-award-1.1277008 (accessed 11/2016).

7 MLB scouting reports supplied by Bill Nowlin.

8 Susan Slusser; Ted Berg, “Major League Baseball’s Last Screwball Pitcher,” USA Today Sports-For the Win, March 16, 2016, ftw.usatoday.com/2016/03/hector-santiago-los-angeles-angels-screwball-fip-era-outlier-mlb (accessed 11/2016).

9 MLB scouting report.

10 The Sporting News, May 24, 1999: 25.

11 Marc Topkin, “Mecir Finds a Pennant Race, if Not Good Eats,” St. Petersburg Times, September 12, 2000, sptimes.com/News/091200/Sports/Mecir_finds_a_pennant.shtml (accessed 3/2/2003).

12 Susan Slusser.

13 CNNSI.com, Sports Illustrated-Baseball Jim Mecir player page,CNNSI.com, Sports Illustrated-Baseball. sportsillustrated .cnn.com/baseball/mlb/players/3328/ (accessed 3/2/2003); USA Today Baseball Weekly, August 28-September 3, 2002: 13.

14 CNNSI.com, Sports Illustrated-Baseball.

15 sptimes.com/News/091701/Sports/Baseball_briefs.shtml.

16 USA Today Baseball Weekly, August 28-September 3, 2002.

17 Ibid.

18 The Sporting News, December 2, 2002: 64, and January 6, 2003: 57.

19 “Jim Mecir Voted 2003 Tony Conigliaro Award Winner,” MLB Official Info-Press Release, December 12, 2003, oakland.athletics.mlb.com/news/press_releases/press_release.jsp?ymd=20031212&content_id=615923&vkey=pr_oak&fext=.jsp&c_id=oak (accessed 11/2016).

20 Bill Center, “Shoulder Surgery Bagwell’s Only Hope,” San Diego Union-Tribune, May 25, 2005, legacy.sandiegouniontribune.com/uniontrib/20050522/news_1s22bbhorn.html.

21 Andrew Martin, “An Interview with Former Relief Pitcher Jim Mecir,” Seamheads.com, December 13, 2015. seamheads.com/blog/2015/12/13/an-interview-with-former-relief-pitcher-jim-mecir/ (accessed 11/2016); Jim Mecir Facebook page, accessed December 2, 2016.

22 “Athletes with Clubfoot – Jim Mecir, Major League Baseball Relief Pitcher, Oakland Athletics,” Clubfoot Support Group, Seekonk, Massachusetts, xprss.com/clubfoot/credetials.asp (accessed 9/4/2002). Rick Williams quote taken from Marc Topkin,“Devil Rays Day by Day,” St. Petersburg Times, March 3, 1998.

Full Name

James Jason Mecir

Born

May 16, 1970 at Bayside, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.