Jim Mooney

Although he recorded a surprising six straight victories (and a 7-1 record) as a New York Giants rookie after his August 1931 debut, and was later a member of the 1934 St. Louis Cardinals’ champion Gas House Gang, Jim Mooney was much more than a professional baseball player.

Although he recorded a surprising six straight victories (and a 7-1 record) as a New York Giants rookie after his August 1931 debut, and was later a member of the 1934 St. Louis Cardinals’ champion Gas House Gang, Jim Mooney was much more than a professional baseball player.

He was also a scholar, teacher, university professor, baseball coach, naval officer and war hero, and veterans adviser. A great believer in education, Mooney wanted to prepare his players and students for life after baseball and the college campus.

A quiet, patient, and easygoing gentleman with a nonjudgmental demeanor and a good sense of humor, the 5-foot-11, 168-pound left-handed hurler played four years (1931-1934) with the Giants and Cardinals, posting a 17-20 record and a 4.25 earned-run average in 92 games. He also had a 16-season minor-league career, which included two feats that rated a mention in Ripley’s Believe It Or Not. According to his daughter Jeanne, “He truly loved the game and was proud of the doors it had opened for him.”1 From Jim’s perspective, baseball “was a rugged and tough life but just putting on a major-league uniform was the greatest thing in the world.”2

James Irving Mooney was born on September 4, 1906, in Mooresburg, a rural hamlet in the hills of northeastern Tennessee. He was the youngest of four children born to Robert C. and Rebecca A. (Isenberg) Mooney, having a brother, Charles, and a sister, Love, who were five and two years older. Tragedy struck the family twice shortly after Jim’s birth. His father, a sawmill worker, died in 1907 at the age of 36 from a cerebral hemorrhage. Eula, his oldest sister, died in 1908 at the age of 6. His mother, Rebecca, an Ohio native, married J. Coleman Hicks a year later; he was a neighbor and 29 years her senior.

Jim grew up on Hicks’ Snow Flake farm on the outskirts of Mooresburg. According to his nephews, he learned to pitch there; as he walked down the road and through the fields, he would throw stones, apples, or corncobs at fence posts, knotholes, bottles, and other targets instead of doing his chores. In the opinion of Mooney’s daughter, these tales “sound very much like one of his ‘I grew up in the country’ stories that he loved to tell as long as he had a gullible listener.”3

Mooney first played sports at Mooresburg High School. In 1924 his mother, a strong-willed woman who stressed education, sent him to East Tennessee State Normal School in Johnson City for his last year of high school. Though technically still a high-school student, Mooney turned out for college coach Jim Luck’s spring baseball tryout. Faced with a shortage of players and impressed by the 17-year-old’s strong left arm, Luck gave him a uniform and named him starting pitcher for the first game, against the Emory and Henry College Wasps, an 11-0 win. It was the first of 13 wins that gave East Tennessee its only undefeated season; Mooney pitched every game.

A fastball pitcher, Mooney specialized in strikeouts. According to The Sporting News, “Mooney started early to establish a reputation for shutouts, whiffing 116 batters in eight games while at Eastern [sic] Tennessee Teachers College.”4 Another publication said he averaged 11 strikeouts per game during his four-year college career. In 1927, his final season, he continued to torment Emory and Henry College, striking out 24 batters in an 11-inning 1-0 win against another future major leaguer, Monte Weaver, who fanned 19. On May 3, in a 4-3 win over the Wasps, Mooney struck out 17 and allowed only four hits.

An all-around athlete, Mooney was also a star halfback for the East Tennessee football team and a standout basketball player, although both teams were less successful than the baseball club.

During his college years, Mooney earned expense money by working summer jobs for coal-field companies in Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky, pitching for their baseball teams on weekends. According to author L.M. Sutter, “Dorchester’s reputation for hiring ringers was as notorious as its field [in Virginia]. In [1924] operators at the camp hired a young southpaw … named Jim Mooney before he was snagged by the Sally League.” “[He] shone as a Dorchester Cardinal,” and teams “repeatedly suffered at the hands of [the] future New York Giants pitcher.”5 In 1925 and 1926, Mooney played at Mascot, Tennessee, and Secco, Kentucky.

On June 10, 1927, Mooney signed a contract with the Chattanooga Lookouts of the Class A Southern Association and made his first professional appearance in the sixth inning of an 11-5 loss to the Mobile Bears, surrendering two runs in three-plus innings. Three days later he made his first start and, in the opinion of the Augusta Chronicle, “showed promise” in a 5-0 loss.6 Mooney’s first victory came on June 26, a 10-5 verdict over Atlanta. Although he gave up 14 hits, the New Orleans Times-Picayune said, “Mooney …pitched good ball but was handicapped by [the] listless fielding of his mates.” 7 Mooney pitched in 21 games for the Lookouts (59-94, seventh), posting a 4-4 record and a 6.63 earned-run average in 76 innings.

Mooney returned to Chattanooga in 1928, had a loss and a win in his first two games, and, after two weeks, was sent to Columbus (Georgia) of the Class B Southeastern League. A 4-3 win in relief against Tampa on May 18 was an early highlight, but a 6-0 loss to Tampa on July 2 found him wild and ineffective, a result that typified his 6-13 record and 4.20 ERA in 30 games. Nevertheless, he was returned to Chattanooga in August and finished his 3-3 season (11 games, 4.34 ERA) on a high note with a 6-1 six-hitter against Nashville.

Back in Chattanooga in 1929, Mooney pitched five innings of one-hit ball against Grover Cleveland Alexander and the St. Louis Cardinals in an exhibition game on April 7 in Chattanooga and earned the win.8 “Jim Mooney,” raved the Times-Picayune, “has been casting joy, refined and unrefined, into Manager Jimmy (Johnston’s) heart. This youngster stood the lordly Cards on their heads last Sunday, allowing them one hit and a string of goose eggs in five innings.”9

A 10-0 loser in his first start against Atlanta, Mooney rebounded to win three straight by May 7. Thereafter, six consecutive losses prompted Johnston to use him in relief. Control was Mooney’s biggest problem; by mid-July, he had a 3-9 record (5.10 ERA), led the league in wild pitches, and was among the league leaders in walks. Another demotion followed, this time to Spartanburg, South Carolina, to play for the Spartans of the Class B South Atlantic (Sally) League. Mooney’s performance was only marginally better for the last place (59-84) Spartans; he was 6-10 on the mound with a 4.86 ERA.

Meanwhile, Mooney took offseason classes at East Tennessee State Teachers College and received his bachelor’s degree in industrial arts in 1929. He then moved to Erwin, Tennessee, where he lived at the YMCA, taught industrial arts, and coached girls’ basketball at Unicoi High School. He continued to teach during the winter and play baseball during the summer for most of the next 18 years.

Mooney trained with Chattanooga in 1930 but lacked control and was released. Signed by the Sally League’s Charlotte Hornets in early June, he showed a good command of his pitches during early starts; on July 16, he set down the Asheville Tourists 2-1 on four hits. With attendance in ballparks lagging throughout the US due to the effects of the Depression, night games were introduced to generate more fan interest. Two and a half months after the first night game in professional baseball (at Western League Park in Des Moines, Iowa), Mooney pitched the game of his life, striking out 23 batters and giving up only five hits in a 7-3 Charlotte win in the first night game played at Municipal Stadium in Augusta, Georgia, on July 19, 1930. His performance caught the attention of major-league scouts for the first time in his life (and a mention in Ripley’s Believe It or Not).

Mooney’s mound dominance led Charlotte manager Dick Hoblitzel to recommend that New York Giants manager John McGraw travel south to see him in action. Though Mooney’s 11-11 record and 3.95 ERA in 189 innings for the Hornets may not have been eye-catching, McGraw was impressed with the hurler’s potential. “Giants Buy Southpaw. Mooney, Promising Charlotte Youngster to Report in Fall” read a headline in the New York Times on August 7, 1930.10 The Giants reportedly paid between $7,000 and $10,000 for Mooney’s contract. With the Giants in a tight pennant race at the time, rumors that the Sally League All-Star would join the team proved incorrect.

On February 22, 1931, Jim Mooney reported to the Giants’ spring-training camp at San Antonio, Texas. He pitched three innings in a 3-1 exhibition loss to the Texas League’s Dallas Steers on March 15, and the Dallas Morning News said that he “showed some good southpaw stuff.”11 On April 12, pitching for the Giants’ second team, Mooney defeated the Eastern League’s Bridgeport Bears 3-1, giving up six hits and striking out seven. After the game he was one of eight players who were assigned to the Bridgeport (Connecticut) Bears in the Class A Eastern League. In the opinion of TSN, Mooney “appears to need some polishing to fit him for major league duty.”12

At Bridgeport, the “sure-fire prospect” was developed by McGraw’s former player and trusted coach, Hans Lobert.13 “It seems like fate has been against me this spring,” Mooney wrote dejectedly to his brother, Charles, about his demotion to the minors.” Acknowledging stiff competition from the Giants’ staff, he vowed to make it to the big leagues. “There are these old timers on the Giants club so I do not have much chance with them, however, I am still going to give somebody a battle.”14 With the Bears, Mooney blossomed into the league’s best pitcher, winning 17 contests, losing just 4 (all to eventual champion Hartford), and posting a microscopic 1.69 ERA.

“My dream has come true or perhaps not a dream but hard work,” Mooney wrote Charles on August 8, 1931. “I am reporting to the Giants tomorrow and boy I sure hope I can stay with them.”15 Upon his arrival, McGraw placed him under the tutelage of former pitching great, future Hall of Famer, and current Giants coach Chief Bender. On August 14 against the Pittsburgh Pirates at the Polo Grounds, Mooney debuted with a sparkling nine-hit complete-game victory, surrendering just one run. “Mooney Recalled from Bridgeport. Fans Seven in Auspicious Big League Debut” reported the New York Times the following day.16 Dan Daniel of the New York World-Telegram called it “one of the most impressive debuts by a New York recruit in ten years and stamped Mooney as a slinger of more than interesting possibilities. The manner of his entry on the stage was quite dramatic.”17 After two relief appearances (winning one of them), Mooney tossed his first career shutout in his second start, blanking the Cincinnati Reds on four hits while striking out six on August 22. “This youngster seems to have given the club’s staff just what is needed to settle into a winning stride, reported The Sporting News.18

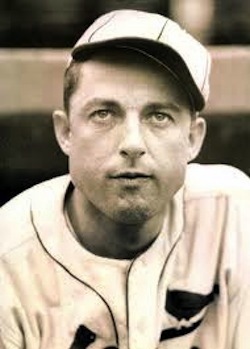

With his great curveball and fastball with “burning speed,” Mooney was making a name for himself as a strikeout artist and was called the modern version of Rube Waddell.19 The Wisconsin State Journal reported that opponents taunted Mooney during games by yelling that they “didn’t have to teach school in the winter” to earn a living.20 Despite the taunts, Mooney kept winning. After his triumph over the Cubs on August 26, he pitched for the first time in an opponent’s ballpark and shut out the Boston Braves at Braves Field on September 1 surrendering eight hits. “Mooney of Giants Quells Braves 4-0. Young Southpaw Breezes to an Easy Victory” read the New York Times subheading about his accomplishments.21 When he beat Brooklyn 10-1 in his next start (the only run the Dodgers scored was unearned), Mooney ran his record to 5-0 and lowered his ERA to 0.77 with just four earned runs in 46? innings. “Mooney Scores Sixth Straight Triumph for McGrawmen in Nightcap” ran yet another subheading in the New York Times about the 24-year old’s dreamlike season.22 Accompanying the article was a picture of Mooney with his cap slightly cocked to the side in a style common at the time. In that game the notoriously bad-hitting Mooney (11-for-105 for a .105 major-league batting average) registered one of his six career RBIs.

Mooney finished the season with a 7-1 record, including six complete games, two shutouts, and a 2.01 ERA in 71? innings. “I have never seen a newcomer pitch with more confidence and skill” said a delighted McGraw about Mooney’s success.23 Celebrated around the city, the “sensational southpaw” capitalized on his notoriety and went on a barnstorming tour after the season with some other members of the Giants, including Ethan Allen, Chick Fullis, Doc Marshall, and Johnny Vergez.24 In late February 1932, TSN reported on his successful duck hunt in the Mooresburg Valley, showing him with three of the six mallards he bagged.

The 1932 Giants were counting on improved pitching to help them contend for the pennant. John McGraw had returning starters Bill Walker, Freddie Fitzsimmons, and Carl Hubbell to anchor the rotation, and much was expected of Jim Mooney, who received a “substantial increase in salary” enabling him to resign his high-school teaching position.25 After a few weeks of training in Los Angeles, the press wasn’t sure that optimism was warranted. When Mooney endured a 10-5 exhibition loss to the Seals in San Francisco, the New York Times said that he “still appears behind in his home work. … [He] ran full tilt into trouble as early as the second inning,” giving up five hits and four runs.26 Off to a rough start to begin the season, Mooney wrote his brother, “Perhaps you are wondering why I have not been winning any ball games. It seems that I am unable to keep off of the injured list. I stepped on a base ball bat two weeks ago and I sprained my ankle pretty bad and I am not over it yet.”27 Unable to generate the power he needed to throw strikes, Mooney struggled, lost velocity, and was wild “like a jack rabbit.”28 He lost his first four decisions and struck out just nine batters in 22 innings, but most concerning to McGraw was his 9.00 ERA at the end of May. Mooney revealed 45 years later that the injury caused him to change his stride and arm problems developed that he never overcame.

With the Giants struggling at 17-23, McGraw announced his retirement and was succeeded by player-manager Bill Terry. Mooney registered victories in his first two starts under Terry, including a complete-game 3-2 triumph over the Reds on June 9. After starting on an irregular basis and pitching in long relief for most of June and July, Mooney made eight consecutive starts from July 31 to September 5, but could not replicate the consistent magic from the previous season. Nonetheless, his masterful four-hit shutout over the cellar-dwelling Reds on August 17 suggested that the 25-year old still had the potential to be a bona-fide major-league pitcher. He finished his first full season in the majors with a disappointing 6-10 record and 5.05 ERA in 124? innings.

On October 10, 1932, the Giants traded Mooney, outfielder Ethan Allen, catcher Bob O’Farrell, and pitcher Bill Walker to the St. Louis Cardinals for catcher Gus Mancuso and pitcher Ray Starr. Cardinals manager Gabby Street thought that Mooney’s pitching woes resulted from the Giants’ attempt to transform him from a high fastball pitcher into a low-ball pitcher. “Don’t forget this Jim Mooney we got from the Giants,” bragged Cardinals owner Sam Breadon. “Street and [Branch] Rickey like him.”29 When asked about the trade, Mooney said he wasn’t surprised; “I will give Gabby Street everything I have and will try to make a good man for his club. I think I will like to play for St. Louis, for they are the one team in the National League that has a pennant-winning fever. And I will do all in my power to help bring the pennant to St. Louis next year.”30 Before Mooney played in his first regular-season game with the Cardinals, rumors swirled that he’d be traded along with Pepper Martin to the Chicago Cubs for Mark Koenig and cash; however, the deal fell through.31

On October 17, 1932, Mooney married Maude Elizabeth “Sweetie” Wilkinson, an Erwin, Tennessee, native, in Sylva, North Carolina, their new offseason home. They had three daughters, Jeanne, Susanne, and Judith.

Mooney’s 1933 season started with promise. He was effective (three hits, one run, seven innings) in relief of loser Dazzy Vance in a 4-0 loss to Pittsburgh on April 23. He also started, went seven innings, and lost a 2-0 four-hitter at Pittsburgh on April 28. In his next outing, on May 4, he tossed a six-hitter, beating the Phillies 5-2 at Shibe Park for his first victory of the season. By mid-May his ERA was 2.10 in 34? innings. Mooney’s season soured on May 18 in a Sportsman’s Park start against Brooklyn. In two-thirds of an inning, he faced eight batters and surrendered four hits, two walks, and six runs in a 14-5 loss. He won his next start, on May 28, a 5-3 victory over Philadelphia, despite giving up 11 hits and four walks. Thereafter, Mooney started only two more games, pitching four innings or less in his last 13 appearances; he seldom saw action after his ERA ballooned to 4.06 in early July. His last appearance of the season came on July 26 when he preserved a 3-2 win for Bill Hallahan with three innings of one-hit, scoreless relief. In August the Cardinals were losing ground to first-place New York and were behind by six games in midmonth. According to TSN, “Gabby [Street] would not be having his troubles today if Bill Walker and Jim Mooney … had come up to expectations.”32

It came as no surprise, then, when Mooney, who had come down with tonsillitis, was sent to Rochester of the International league to recuperate. In a disastrous first start, he gave up two home runs (and six RBIs) to Baltimore’s Moose Solters, the league batting champion, during an eight-run fourth inning in a 12-3 loss on August 18. Mooney was 2-3 in seven appearances for the Red Wings, two of which were against Buffalo in the playoffs. Recalled by St. Louis in mid-September, he did not see action.

Invited to the Cardinals’ 1934 spring-training camp in Bradenton, Florida, Mooney arrived without fanfare, but his erratic performances continued. Making the team as the left-handed relief specialist, Mooney was part of one of the most cherished and fabled World Series championship teams, the Gas House Gang, so named because of their unkempt, shabby appearance and scrappy play. “Mooney is Star as St. Louis Gains 11th Victory in 12 Starts,” read the New York Times subhead after he pitched six innings of relief to earn his first win of the season.33 With a career-high 32 appearances, including seven spot starts spread out over the season, Mooney won two and lost four (all four losses were in games he started), and posted a 5.47 ERA in 82? innings, but did not pitch in September when the Cardinals overcame a seven-game deficit to the New York Giants to win the pennant in dramatic fashion on the last weekend of the season.

A game against the Giants was notable: On June 27, Dizzy Dean held a 7-6 lead going into the top of the ninth inning. With two outs, the Giants tied the score and Mooney was brought in and got the third out. St. Louis then won the game in the bottom of the ninth, 8-7, and because Mooney was the pitcher of record when the score was tied, the official scorer gave him credit for the victory. However, in a reversal reminiscent of a decision made on a June 23 Cardinals’ win against the Dodgers, National League President John Heydler again invalidated an official scorer’s decision and gave the win to Dean. Both decisions gave Dean an even 30 wins. Mooney got one less win out of the decision but recorded his second major-league save (the save is retrospective; the statistic was not created until three decades later).

The Gas House Gang won the World Series by winning Games Six and Seven (the latter was Dean’s dominating shutout) over the Detroit Tigers and securing their place in baseball lore. Pitching for the first time since August 27, Mooney saw mop-up duty in the Cardinals’ Game Four 10-9 loss. Allowing one hit in one inning, Mooney pitched for the last time in the major leagues and finished as a champion

With the press reporting that he’d lost some zip from his fastball, the Cardinals sold Mooney’s contract to the Columbus (Ohio) Red Birds of the American Association on January 2, 1935. Posting a 17-20 record and a 4.25 ERA in 356 innings in a four-year big-league career, Mooney never made it back to the majors; however, he continued to pitch in professional baseball until 1948 and remained involved in the sport for the rest of his life.

Keeping in shape by playing basketball for the Erwin team in the Appalachian Independent Basketball Conference during the winter, Mooney reported to the Red Birds’ spring training hoping to jump-start his career. After eight appearances and 37 innings of work, he was the league’s top pitcher at the end of May with a 3-0 record. Thereafter, he was 1-4, finishing with a 4-5 mark and a 6.17 ERA in 29 games, mostly in relief. By mid-August he was optioned to the International League’s Baltimore Orioles. Mooney pitched well in his debut against Rochester on August 18, but lost 1-0 on a run-scoring wild pitch. Four days later, he triumphed over Syracuse, 8-3, fanning nine. After three more losses, his final Baltimore record was 1-4.

Ineffective in three stints at the highest minor-league level, Mooney was optioned by the Cardinals to the Memphis Chicks of the Southern Association in 1936, and was 2-0 in three games. In mid-May he was transferred to the Knoxville Smokies of the same circuit, where he struggled, finishing with a 3-12 record. In a combined 41 games for both teams, his record was 5-14 with a 5.21 ERA in 186? innings.

Taking yet another step down the minor-league ladder, Mooney was with the Southeastern League’s Mobile Shippers in 1937 and 1938. The Shippers won the league championship and the Little Dixie Series (Class B championship of the South) both years. In 1937 Mooney (16-11, 2.90 ERA) won four straight games in the playoffs, completing one of his most successful minor-league seasons.

During the fall Mooney took a faculty position at Tennessee High School in Bristol, Tennessee, where he taught industrial arts. During the winter he refereed basketball games; in the spring, he was a track and field official for the Big Six Conference.

In the spring of 1938, Mooney pitched for the amateur Saltville Alkalies in Virginia’s newly organized Burley Belt League. He then returned to Mobile. Mooney (10-7, 2.65 ERA) didn’t play in Mobile’s Little Dixie Series triumph over Macon, instead returning to Bristol to teach.

Still in the Cardinals’ chain, but now closer to home, Mooney was assigned to Asheville of the Piedmont League in 1939. With four 12-win pitchers, a speedy infield that turned a league-record 165 double plays, and an abundance of clutch hitting, manager Hal Anderson’s youthful Tourists (89-55) sprinted to the regular season championship by a league record 14-game margin over Durham.

Mooney (14-7) was one of three (past and future) major-league hurlers, along with Red Munger (16-13) and Hersh Lyons (12-1). Moose Fralick (12-1) was equally as good, and catcher Walker Cooper was a year away from starting his 18-year major-league career. “Mooney,” Anderson told the Richmond Times-Dispatch, “has helped our young pitchers a lot by correcting glaring faults in the way they throw curves and other pitches.” 34 His most important victory came on September 18, when he pitched a 4-2 six-hitter against Rocky Mount to clinch the playoff championship.

Mooney’s second Ripley’s Believe It Or Not moment came during one of his Asheville relief appearances. He entered the game with one out and runners on first and third, and retired the side without throwing a pitch. His pickoff attempt to first resulted in a rundown; the runner was tagged out and a throw to Cooper got the runner from third trying to score.

After enrolling in graduate school at the University of Tennessee in the fall of 1935, Mooney spent four offseasons attending classes before receiving his master’s degree in industrial education in August 1939. Shortly thereafter, East Tennessee State President C.C. Sherrod hired him as a professor and baseball coach.

Mooney was out of Organized Baseball in 1940 but hadn’t lost his desire to play. In May 1941 he pitched for the Johnson City Soldiers semipro team. By late July, Mooney was purchased from Asheville by his hometown Johnson City Cardinals of the Appalachian League. It was an ideal setup for him. Once college was in session, he could teach classes during the day and play ball in the evening. On July 27 Mooney saved a game against Newport; his first win was in relief on July 29, a 5-4 victory over Kingsport. The Kingsport Times noted that “he had plenty of steam on his fast one,” but “was not in the best of shape.”35 On August 27 Mooney (8-2, 2.44 ERA) gained his eighth straight triumph by scattering ten hits and fanning 17 Greeneville batters in a 5-1 Johnson City win. The fourth-place Cardinals (63-57) lost the league playoff finals to Elizabethton, three games to one.

The 35-year-old Mooney (15-11, 2.11 ERA) was a workhorse for Johnson City in 1942, leading the league with 192 innings pitched; two sources noted that he was never relieved and didn’t issue a single walk all year. On July 26 he took over as interim manager when Mercer Harris was indefinitely suspended after a run-in with an umpire.

In November 1942 Mooney resigned from East Tennessee State, reported for duty in the US Navy and was commissioned as a lieutenant junior grade. After training in Boston and New Orleans, Mooney was sent to San Francisco in February 1943 and by May he was at sea, just “floating around from place to place.”36

In April 1944 Mooney returned to the States for more training and to pick up his new crew of five officers, 104 enlisted men, and a landing ship tank, LST-555, in Chicago. They were soon deployed in the South Pacific, where they participated in eight major landings as the US forces drew ever so close to Japan. Their last major operation was the assault and occupation of the Okinawa island group from April through June of 1945, a dangerous time given that they served as an ammunition ship that could be targeted by kamikazes.

LST-555 endured four typhoons during these operations. During the final (and worst) typhoon the vessel grounded off Wakayama, Japan, and was rendered unsalvageable. The ship earned four battle stars. Mooney, who was mustered out as a lieutenant commander, was cited for “personal courage and leadership in performing duties and accomplishing designated assignments under regulated enemy air attack.”

Mooney returned to Johnson City in January 1946 after 25 months at sea. Shortly thereafter, he resumed his duties as a professor and coach at East Tennessee State, with an added role – veterans’ adviser. He also returned to the diamond. On June 21 he pitched the Bristol State Liners to a 12-3 win over Cavalier Grill in a semipro Burley Belt League game. Ten days later he signed with the Johnson City Cardinals and posted an 8-7 record and a 3.05 ERA in 18 games. He returned in 1947 at the age of 40, won his first start on May 11, compiled an 8-2 record by early July, was named to the Appalachian League All-Star team, and was the winning pitcher in the all-star game. Mooney (13-7, 2.92 ERA) was the Cardinals’ best pitcher in 1947, walking only 16 men in 22 games. Despite his fine work, the Cardinals gave him his outright release after the season. “I still feel like I’ve got some pitching days left,” he told the Kingsport News. “I don’t have any plans now, and next summer is still a long way off. If I don’t pitch in professional ball, I may hook up with a semipro team.”37

On October 19 a team of barnstorming major leaguers stopped in Johnson City to play a team managed by Mooney. The major leaguers prevailed, 7-1.

Mooney pitched on summer weekends for the Blue Ridge League’s Abingdon (Virginia) Triplets in 1948. (The club started the season in Leaksville-Draper-Spray but the frtanchise was forfeited when the team owner became embroiled in a game-fixing scandal in mid-May, and new owners moved it to Abingdon.) Abingdon (43-81) finished the season in last place. Mooney appeared in 12 games, posting a 7-5 record (and 3.32 ERA) in his last professional season. One of his better efforts was an 8-0 six-hit shutout of Radford on August 21.

In 16 minor-league seasons, Mooney’s record was 153-137 (3.39 ERA). He continued to play semipro baseball for several more years; in July 1950, he pitched a 6-0 shutout for Saltville in the Burley Belt League, giving up five hits and fanning 12 Gate City Moccasins. In 1953 the Kingsport Times-News mentioned that he was still active in semipro circles.

In his second stint (1946-1965) as East Tennessee State’s baseball coach, Mooney’s record was 142-147-1. His best teams were in 1946-48 when they were a combined 24-10. Mooney often took a few of his players to Burley Belt games so they could earn extra expense money before NCAA rules prohibited such activity. One of Mooney’s players, infielder Ernie Bowman, went on to play in the major leagues (San Francisco, 1961-63).

Mooney rose to the position of assistant to the dean during his last 28 years at East Tennessee State. Besides coaching baseball and teaching engineering drawing and other industrial arts, he helped thousands of veterans in his role as veterans’ adviser. By the time he retired in June 1974, he was regarded as one of the foremost authorities on veterans’ affairs in Tennessee.

Baseball was always Mooney’s main interest. If a World Series game was on TV, he could be found in his office with a group of students watching the game. According to his daughter, when he was at home he could listen to two games on the radio and watch one on TV. In his spare time, he was a Little League coach for many years and made sure that every boy got to play, sometimes to the chagrin of some of the parents. He was also a popular speaker at banquets and other community gatherings. When asked, he would share baseball stories, often relating funny incidents about Dizzy Dean and others from the Gas House Gang. He enjoyed traveling to St. Louis for a Gas House reunion in June 1959.

Mooney kept busy during his retirement. He had a woodworking shop in his basement and enjoyed making gifts and toys. He planted a garden every spring and produced enough vegetables to share. Family gatherings and reunions were favorite pastimes; each new grandchild was warmly welcomed into the family.

Mooney was inducted into the East Tennessee State University Athletics Hall of Fame in 1977. He died at 72 from heart failure on April 27, 1979, in Johnson City, and was survived by his wife, Elizabeth, and three daughters. He is buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Erwin, Tennessee. In 1980 ETSU’s new on-campus baseball facility was named Mooney Field.

This biography originally appeared in “The 1934 St. Louis Cardinals The World Champion Gas House Gang” (SABR, 2014), edited by Charles F. Faber.

Sources

Wes Singletary, Florida’s First Big League Baseball Players: A Narrative History (Charleston, South Carolina: History, 2006).

George Stone, Muscle, a Minor League Legend (Haverford, Pennsylvania: Infinity Pub., 2003).

L.M. Sutter, Ball, Bat, and Bitumen: A History of Coalfield Baseball in the Appalachian South (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009).

Melvin D. Barger, “Large Slow Target: A History of Landing Ships (LSTs) and the Men Who Sailed Them,” Volume II (Oregon, Ohio: U.S. LST Association, 1989).

Allen Green, “Baseball No Fun Anymore, Old Jim Mooney Asserts.” Bridgeport (Connecticut) Sunday Post, April 3, 1960, C13.

“Half Century at State.” Alumni Quarterly – East Tennessee State University 38.3, (Spring 1974), 8-9.

Jack Mooney, “Jim Mooney.” Hawkins County Historical Society (n.d.), 387-89.

Richard Moore, “ETSC’s Jim Mooney Holds Several Titles At School.” Kingsport Times-News, June 3, 1962, 39.

George Stone, “Jim Mooney Made Hit with 1931 New York Giants.” Johnson City Press-Chronicle, April 10, 1977, 36.

Ancestry.com

Baseball-reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Jim Mooney player file

The Sporting News

Richmond (Virginia) Times-Dispatch

Kingsport (Tennessee) Times, Kingsport News

New York Evening Graphic

Chattanooga Times

Morning Advocate (Baton Rouge)

Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle

Times Picayune (New Orleans)

Tampa Tribune

Salt Lake Tribune

Hartford Courant

Washington Post

New York Times

Omaha World Herald

Boston Herald

Trenton (New Jersey) Evening Times

Olean (New York) Times Evening Herald

Dunkirk (New York) Evening Observer

Salamanca (New York) Republican Press

Dallas Morning News

National Labor Tribune (Pittsburgh)

Panama City (Florida) News-Herald

Biloxi (Mississippi) Daily Herald

Greensboro (North Carolina) Record

Johnson City (Tennessee) Press-Chronicle

Wisconsin State Journal (Madison)

Jim Mooney Letters, 1931-1946, Archives of Appalachia, East Tennessee State University.

Notes

1 Letter to Charlie Weatherby from Jeanne Mooney Smith, June 2012

2 George Stone, “Jim Mooney Made Hit with 1931 New York Giants,” Johnson City Press-Chronicle, April 10, 1977, 36.

3 Jeanne Mooney Smith letter.

4 “His Speed Burns Them Up,” The Sporting News, September 10, 1931, 1.

5 L.M. Sutter, Ball, Bat, and Bitumen: A History of Coalfield Baseball in the Appalachian South (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 33, 55.

6 “Vols 5, Lookouts 0,” Augusta Chronicle, June 14, 1927, 6.

7 “Eight-Run Rally Wins for Lookouts, 10-6,” Times-Picayune, New Orleans, June 27, 1927, 16.

8 “Training Camp News. Cardinals are Defeated,” Pittsburgh Press, April 8, 1929, 17.

9 “Outfielders Main Worry of Lookouts,” Times-Picayune, April 14, 1929, 81.

10 “Giants Buy Southpaw,” New York Times, August 7, 1930, 29.

11 George White, “Garland and Erickson Tame Giants as Steers Win Third Straight,” Dallas Morning News, March 16, 1931, 12.

12 “Caught On The Fly,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1931, 6.

13 “Caught On The Fly,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1931, 6.

14 Letter from Jim Mooney to his brother Charles. Undated [1931]. Jim Mooney Letters, 1931-1946, Archives of Appalachia, East Tennessee State University (hereafter cited as Jim Mooney letters).

15 Jim Mooney letters.

16 John Drebinger, “Giants Rookie Stops Pirates by 2-1,” New York Times, August 15, 1931, 11.

17 Dan Daniel, “Giants Gloat Over Mooney Despite Cardinal Invasion,” New York World-Telegram, August 15, 1931.

18 Joe Vila, “Rookie Gives Giants Fresh Lease of Life,” The Sporting News, August 27, 1931, 1.

19 Joe Vila, “Sterling Pitching Puts Giants Back in National Pennant Race,” The Sporting News, September 10, 1931, 1.

20 Roundy Coughlin, “Roundy Says,” Wisconsin State Journal (Madison), October 24, 1931, 2.

21 “Mooney of Giants Quells Braves 4-0,” New York Times, September 2, 1931, 25.

22 “Mooney Scores Sixth Straight Triumph for McGrawmen in Nightcap 4-3,” New York Times, September 9, 1931, 32.

23 “Both New York Teams Gather Timber Early For Next Year,” The Sporting News, August 20, 1931, 1.

24 Ralph S. Davis, “Bucs Want Neither Malone Nor Davis,” The Sporting News, September 17, 1931, 3.

25 John Drebinger, “Lindstrom Joins Giants’ Hold-Outs,” The New York Times, January 19, 1932, 27.

26 John Drebinger, “Giants Are Beaten By Seals, 10-5,” New York Times, April 3, 1932, 5J.

27 Jim Mooney letters.

28 Jim Mooney letters.

29 John Kieran, “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, February 7, 1933, 24.

30 “Mooney Glad He’s Card,” Mooney Hall of Fame Clipping File, November 3, 1932.

31 Edward Burns, “Hazen Cuyler Lost to Cubs Until June,” The Sporting News, April 6, 1933, 1.

32 “Hornsby Looms Up In King Row As Next Leader of The Browns, “The Sporting News, July 20, 1933, 1.

33 John Drebinger, “Cardinals Conquer Giants 5-4,” New York Times, May 11, 1934, 28.

34 “Tourists Seek to Establish New League Winning Record,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 30, 1939, 9.

35 “Jim Mooney Halts Final Attempt Of Frank Massimo,” Kingsport Times, July 30, 1941, 6.

36 Jim Mooney letters.

37 “Jim Mooney Given Outright Release From Johnson City,” Kingsport News, October 2, 1947, 12.

Full Name

Jim Irving Mooney

Born

September 4, 1906 at Mooresburg, TN (USA)

Died

April 27, 1979 at Johnson City, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.