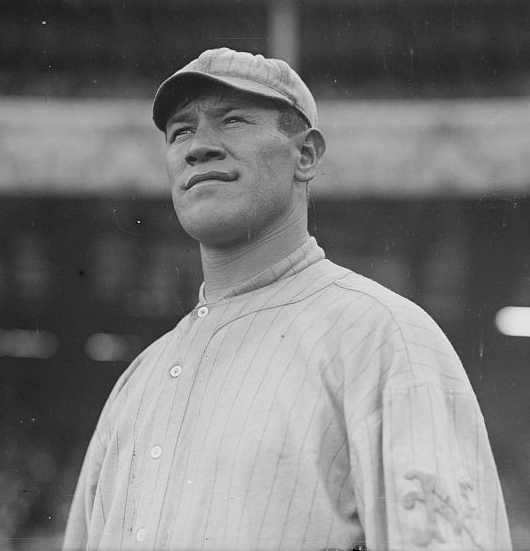

Jim Thorpe

Jim Thorpe was the greatest all-around athlete of the Deadball Era. In addition to playing major-league baseball for six seasons, the 6-foor-1, 185-pound Thorpe was an Olympic champion in the pentathlon and decathlon and at one point the greatest American football player in history, according to a 1977 Sport magazine poll. One sportswriter called him the “most marvelous creation fashioned in human likeness that has ever inhabited the earth,”1 but others described him as simple-minded, lazy, averse to training, and unable to hold his liquor. Thorpe’s disappointing baseball career –he played in 289 National League games and hit only .252 with seven home runs and 29 stolen bases – demonstrated what multi-sport athletes like Michael Jordan have since discovered: that mere possession of superb natural tools doesn’t guarantee success on the diamond. “I can’t seem to hit curves,” Jim admitted. “I believe I could hit .300 otherwise.”2

Jim Thorpe was the greatest all-around athlete of the Deadball Era. In addition to playing major-league baseball for six seasons, the 6-foor-1, 185-pound Thorpe was an Olympic champion in the pentathlon and decathlon and at one point the greatest American football player in history, according to a 1977 Sport magazine poll. One sportswriter called him the “most marvelous creation fashioned in human likeness that has ever inhabited the earth,”1 but others described him as simple-minded, lazy, averse to training, and unable to hold his liquor. Thorpe’s disappointing baseball career –he played in 289 National League games and hit only .252 with seven home runs and 29 stolen bases – demonstrated what multi-sport athletes like Michael Jordan have since discovered: that mere possession of superb natural tools doesn’t guarantee success on the diamond. “I can’t seem to hit curves,” Jim admitted. “I believe I could hit .300 otherwise.”2

Great, great, great grandson of the famed Sauk warrior Black Hawk, James Francis Thorpe was born on May 28, 1887, on the Sac and Fox Reservation near Prague, in the Indian Territory.

Grandson of the famed Chippewa warrior Black Hawk, James Francis Thorpe was born on May 28, 1887, on the Sac and Fox Indian reservation near Prague, in the Oklahoma Territory. His father, Hiram, was a blacksmith who married at least five Native American women and fathered more than 20 children. Because of his early athletic prowess, Jim received the Indian name Wa-tho-huck (“Path Lit by Lightning”) from his mother, Charlotte. He became a disciplinary problem after his twin brother, Charles, died at age 9. Jim’s truancy finally angered his father so much that he sent Jim to the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania in 1904. A vocational institution operated by the federal government to teach Indians industrial skills and integrate them into society, Carlisle was, according to one of its former athletes, “nothing but an eighth-grade school, but they called us a college.”3

In the fall of 1907, legendary Carlisle coach Glenn “Pop” Warner convinced Thorpe to try out for the football team. Jim excelled as a halfback, punter, and kicker, but in 1909 he withdrew from Carlisle (one of several times he left the institution) and worked on a farm in North Carolina. During the summers of 1910-11 he accepted $60 per month to play baseball for Rocky Mount and Fayetteville of the Eastern Carolina League. Encouraged by Warner – and with an eye toward the 1912 Olympics – Thorpe returned to Carlisle in 1911-12. He was sensational on the gridiron against major collegiate foes, and Walter Camp selected him for the All-America football team in both years.

With his triumphs at the Stockholm Olympics in 1912, Jim Thorpe’s fame spread worldwide. “Sir, you are the greatest athlete in the world,” declared Sweden’s King Gustav.4 After the Games, however, Thorpe was forced to return his medals and trophies when the Amateur Athletic Union discovered that he had played minor-league baseball. It was a crushing blow that Jim never overcame. “I did not play for money,” he wrote in a letter to the AAU president. “I was not very wise in the ways of the world and did not realize this was wrong. I hope I will be partly excused by the fact that I was simply an Indian School Boy and did not know that I was doing wrong because I was doing what many other college men had done, except they did not use their own names.”5

Stripped of his amateur status, Thorpe signed a three-year contract in February 1913 for the staggering sum of $6,000 per season to play baseball for the New York Giants, who beat out five other clubs in signing the “red-skinned marvel.”6 It was the most ever paid to a major-league rookie. The agreement included a $500 signing bonus, and Warner received $2,500 for steering Jim to the Giants. “There can be no denying that he is a great prospect,” wrote one observer, “and many critics would not be surprised if, under [John] McGraw‘s careful tutelage, he developed into another Ty Cobb.”7 At the signing ceremony, however, the Giants manager admitted that he had never seen Thorpe in action; he didn’t know what position he played or even whether he hit right- or left-handed (Thorpe was right-handed).

At spring training in Marlin Springs, Texas, Thorpe got off to a rocky start by showing up late for an exhibition game. He received time at first base and the outfield, and it soon became evident that he had difficulty with breaking pitches. During the 1913 season Thorpe was used primarily as a pinch hitter and pinch runner, compiling only 35 at-bats in 19 games and hitting .143 with two stolen bases. “I felt like a sitting hen, not a ballplayer,” he said.8 It wasn’t a happy time. His roommate, Chief Meyers, remembered a night when Jim came in late and woke him up. “He was crying, and tears were rolling down his cheeks,” Meyers recalled. “‘You know, Chief,’ he said, ‘the King of Sweden gave me those trophies, he gave them to me. But they took them away from me, even though the guy who finished second refused to take them.’”9

On the 1913-14 World Tour, Thorpe brought along his first wife (he eventually had three), but McGraw viewed his behavior as inappropriate for a married man and lectured him on the dangers of drinking and playing cards. After playing most of the 1914 season in the American Association with Milwaukee, he spent most of 1915 in the Eastern League, hitting a combined .303 with 22 steals for Harrisburg and Jersey City. While with the latter club Thorpe was sued for his involvement in a saloon brawl, but the former club released him because he had a “disturbing influence on the team.”10

In 1914, he had appeared in 30 games for the Giants, batting .194. In 1915, he only got into 17 Giants games, but hit slightly better — .231. Over his first three seasons, his major-league stats saw him produce only five RBIs in 66 games and 102 plate appearances.

Thorpe was back in Milwaukee in 1916. In the press McGraw insisted that although Jim was still raw, he was a fast learner with excellent instincts and would eventually become a star. Privately, however, the Giants manager was beginning to have his doubts.

After playing in four mid-April games at the start of the 1917 season, Thorpe was loaned by McGraw to the Cincinnati Reds, then managed by Christy Mathewson. “Jim would take only two strides to my three,” said teammate Edd Roush. “I’d run just as hard as I could, and he’d keep up with me just trotting along.”11 Recalled from the Reds on August 1, Thorpe appeared in 26 more games for the Giants and ended the only big-league season in which he appeared in over 100 games with a composite average of .237.

The Giants won the pennant. Thorpe’s only postseason appearance was an odd one. He was in the batting order for Game Five of the 1917 World Series, played at Comiskey Park on October 13. He was in the starting lineup, to bat sixth in the order against southpaw Reb Russell. The Giants scored one run and had baserunners on first and second with two outs. McGraw wanted to get another run home and had the left-handed hitting Dave Robertson pinch-hit for Thorpe against right-handed White Sox reliever Eddie Cicotte. Robertson singled in the second run, and replaced Thorpe in right field. Thus, Thorpe had not played a moment in the game. Ring Lardner wrote, “Jim stayed in the batting order until it was his turn to bat. Then he put his ugly brown sweater back on and resumed his habitual seat in the wigwam.”12

In 1918 he appeared in only 58 games all year, batting .248 with 11 RBIs. and the following season he had appeared in just two as of May 21. After Jim complained about his lack of playing time, the Giants traded him to the Boston Braves for washed-up pitcher Pat Ragan. Thorpe hit .327 in 60 games for the Braves, by far his best major-league performance, but 1919 proved to be his last season in the majors. In each of his six seasons in the major leagues, his batting average improved over the prior year.

All told, Thorpe appeared in 289 major-league games, with a career batting average of .252. He did not draw that many bases on balls (27); his career on-base percentage was .286. He struck out 122 times in 698 at-bats. Thorpe homered seven times, four of them while on loan to the Reds, and drove in 82 runs. He scored 91. As a fielder, his career fielding percentage was .951. He primarily played left field (89 games), right field (72), and center (38), with two games (13 innings total) at first base.

Over the next three years Jim Thorpe played baseball for several minor-league clubs, putting up respectable statistics but focusing most of his energies on professional football, which he had been playing during the offseason since he founded the famous Canton Bulldogs in 1915.

Thorpe had trouble adjusting to life after his career in professional sports. In 1928 he was playing semipro baseball at his home reservation in Oklahoma when he unsuccessfully sought a job with Waterbury of the Eastern League. Two years later, he traveled to Southern California as master of ceremonies for C. C. Pyle’s cross-country marathon. He settled there, working as a ditch digger on a WPA project and as an extra and bit player in motion pictures. Though past the age of enlistment, Thorpe joined the merchant marine in 1945 and served on an ammunition ship.

Between 1931 and 1950, Thorpe appeared in 70 films, a number of which are classics or well-remembered titles. He was a New York theatergoer in the original King Kong (1933); a pirate in Michael Curtiz’s Captain Blood (1935); a “John Doe applicant” in Frank Capra’s Meet John Doe (1941); an Indian in Raoul Walsh’s They Died With Their Boots On (1941); a ship’s passenger in the Bob Hope-Bing Crosby comedy Road to Utopia (1945); a convict in Walsh’s White Heat (1949); and another Indian in John Ford’s Wagon Master (1950). He wore baseball uniforms in Joe E. Brown’s Alibi Ike (1935) and the Buster Keaton short One Run Elmer (1935), and he even appeared as a Carlisle football player in Fighting Youth (1935), a curio involving communist agitators who infiltrate a college campus. Primarily, however, Thorpe played a range of roles in such B-Westerns as Moonlight on the Prairie (1935), Treachery Rides the Range (1936), Cattle Raiders (1938), Frontier Scout (1938), Arizona Frontier (1940), and Beyond the Pecos (1945).

Burt Lancaster played Thorpe in the 1951 biopic Jim Thorpe, All-American. The film depicts his being stripped of his medals for playing minor-league ball. Warner Bros., the studio that produced the film, paid Thorpe $15,000 for his services as technical advisor. Additionally, Mort Blumenstock, the studio’s head of publicity, donated $2,500 toward an annuity fund for Thorpe.13 It was around this time that he also tried to develop a nightclub act. However, after Thorpe underwent an operation for lip cancer in November 1951, newspapers reported that he was penniless.

Jim Thorpe was 65 years old when he died of a heart attack in his trailer home in Lomita, California, on March 28, 1953. Though he’d been operating a nearby bar, his death certificate listed his occupation simply as “Athlete.” Jim’s third wife had his body interred in Shawnee, Oklahoma, before she moved it to Tulsa. In 1957 the body was transferred once again, to Mauch Chunk and East Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania – a place Thorpe had never been. Hoping to transform themselves into a tourist center, the towns merged and renamed themselves Jim Thorpe in his honor. His surviving sons tried to use the courts to have his body returned to Sac and Fox land in Oklahoma. The Third U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, however, ruled in 2014 that Thorpe’s remains should stay where they were. Son Bill Thorpe, though disappointed with the decision, said, “It’s been a good place. They’ve taken good care of him and continued the name.”14

In 1953 the Associated Press selected Thorpe as the greatest American athlete of the first half of the 20th century. He is a member of the Pro Football, College Football, and National Track and Field Halls of Fame. After a long campaign led by Thorpe’s daughter Grace, the International Olympic Committee reversed its 1912 decision on Thorpe’s eligibility in 1983, reissuing his gold medals and adding his name to its list of Olympic champions.

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Photo credit

Jim Thorpe, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Notes

1 “Greatest Living Athlete,” Omaha World-Herald, July 28, 1912: 18. Kate Buford attributes the original quotation to the Philadelphia Inquirer in her book Native American Son: The Life and Sporting Legend of Jim Thorpe (New York: Knopf, 2010).

2 Bob Hersom, “Thorpe Remembered for Baseball Prowess,” The Oklahoman, June 3, 2006.

3 Joe Guyon, quoted in Dave Anderson, “Jim Thorpe’s Medals,” New York Times, June 22, 1975: 199.

4 Associated Press, “Great Jim Thorpe Wants Sons to Follow Diamond, Not Gridiron,” Hartford Courant, April 6, 1940: 11.

5 Robert W, Wheeler, Jim Thorpe, World’s Greatest Athlete (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1981), 145.

6 Des Moines Register, January 9, 1926: 8.

7 Hersom.

8 Ray Robinson, Matty: An American Hero (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 153.

9 William A. Cook, Jim Thorpe: A Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2011), 88.

10 Cook, 138.

11 Charles Einstein, The Fireside Book of Baseball (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987), 322.

12 Ring W. Lardner, “In the Wake of the News,” Chicago Tribune, October 14, 1917: A1. The White Sox won the game in the end, 8-5. They won Game Six as well, winning the World Series, four games to two.

13 Kate Buford, Native Son: The Life and Sporting Legend of Jim Thorpe (New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 2010).

14 Associated Press, “Pennsylvania Town Named For Jim Thorpe Can Keep Athlete’s Body,” CBS News, October 23, 2014. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/pennsylvania-town-named-for-jim-thorpe-can-keep-athletes-body/

Full Name

James Francis Thorpe

Born

May 28, 1887 at Prague, OK (USA)

Died

March 28, 1953 at Lomita, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.