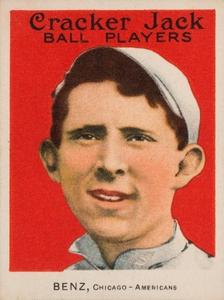

Joe Benz

Until age and arm miseries precipitated his release in May 1919, right-hander Joe Benz was a valuable member of the Chicago White Sox pitching corps. During the preceding eight seasons, Benz had alternated between the starting rotation, spot-starter duty, and long relief, never posting an ERA higher than 2.90. Usually overshadowed by mound mates like Ed Walsh, Red Faber, and Eddie Cicotte, Joe found his moment in the spotlight in May 1914, when he pitched a no-hitter, the fifth in White Sox history. Apart from that and a solid major-league career, he achieved another distinction of sorts: Joe Benz was, by all accounts, a genuinely decent man.

Until age and arm miseries precipitated his release in May 1919, right-hander Joe Benz was a valuable member of the Chicago White Sox pitching corps. During the preceding eight seasons, Benz had alternated between the starting rotation, spot-starter duty, and long relief, never posting an ERA higher than 2.90. Usually overshadowed by mound mates like Ed Walsh, Red Faber, and Eddie Cicotte, Joe found his moment in the spotlight in May 1914, when he pitched a no-hitter, the fifth in White Sox history. Apart from that and a solid major-league career, he achieved another distinction of sorts: Joe Benz was, by all accounts, a genuinely decent man.

The future White Sox hurler was born Joseph Louis Benz in New Alsace, Indiana, on January 21, 1886, the second of four children born to Michael Benz (d. 1941) and his wife, Mary, née Wilhelm (d. 1929).1 The Benz family was of German Catholic stock, Joe’s grandfather, also named Michael, having emigrated from the Grand Duchy of Baden in 1849. Upon arriving in New Alsace, Michael the patriarch established the meat-butchering business that would sustain the Benz clan for the next three generations. In 1892 Joe’s father and two uncles relocated to Batesville, Indiana, where they opened Benz Brothers, on-premise butchers and purveyors of livestock products. The enterprise quickly prospered, affording employment to many in the extended Benz family, including young Joe.2

A strapping youth – baseball references usually list him at 6-feet-1, 194 pounds – Benz began playing baseball for the Batesville Reserves and other local nines at about the age of 14. By 1904 Joe had switched from the outfield to the mound, overpowering area competition with a fastball that earned him the moniker Blitzen (German for lightning) Benz. He also developed a serviceable curve, a knuckler, and the pitch that would become his big-league meal ticket: a quick-breaking spitball.

The date of Benz’s entry into the professional ranks is difficult to pinpoint. One account has him signing a $125-a-month contract with a White Sox scout in 1908.3 Yet local newspapers are replete with accounts of Joe pitching for Batesville that season.4 Those same sources establish that he began the 1909 season with the Clarksburg (West Virginia) Bees of the Class D Pennsylvania-West Virginia League.5 But an early-season arm injury, the first of the throwing ailments that would plague Benz’s career, prompted his release. He returned home to recuperate and was soon in the outfield for the Batesville nine.6 Thereafter, dominant pitching performances, including a 9-0 no-hitter over Aurora on June 20 and a 20-inning, 20-strikeout complete game in a 1-1 tie against the Indianapolis TTs on July 11, 1909, demonstrated that Joe’s pitching arm was again sound, and revived professional interest in him. Benz resumed his pro career in Newark, Ohio, where he posted a 10-7 record for the Newks of the Class D Ohio State League. He also played 12 games in the outfield but managed only a .202 batting average.7 By late season 1909, Benz had been promoted to the Des Moines Boosters of the Class A Western League, where, in sparing work, he made a mark sufficient to gain a roster spot for the 1910 season.8

Benz began that season with Des Moines but pitched erratically in the early going. After an ineffective relief outing against Topeka, Boosters manager George Davis traced the problem to a flaw in Joe’s spitball grip that, if corrected would “make a valuable pitcher out of Benz.”9 But after several more lackluster appearances, Benz was sold to the Green Bay Bays of the Class C Wisconsin-Illinois League.10 He started strongly in Green Bay but had to be shut down with arm trouble shortly after pitching a July 19 doubleheader shutout against Racine, winning each contest 2-0 while fanning 19. A one-hit blanking of Fond du Lac in early September, however, signaled a late-season return to form.11 Notwithstanding the demotion to Green Bay, Des Moines retained interest in Benz, including him on the reserve list submitted to Western League offices at the close of the 1910 season.12 Pitching for a woeful last-place Boosters team in 1911, Benz managed a respectable 10-10 log in 33 games before his contract was purchased by the White Sox.13

Benz made his major-league debut on August 16, 1911, relieving Doc White in an 8-1 loss to Detroit and making a favorable first impression. Sportswriter I.E. Sanborn informed readers, “Benz looked remarkably like a pitcher during the three innings that he worked. He mixed a spitter with good speed and perfect control, and apparently was cool and confident.”14 Benz notched his first win three weeks later, pitching 8⅓ sterling innings against the St. Louis Browns, again in relief of White. By campaign’s end, Joe’s record stood at 3-2, with a 2.26 ERA in 12 games. But the late-inning unsteadiness that would dog him throughout his White Sox career was early in evidence. Manager Hugh Duffy went quick to the hook with Benz, allowing him to complete only one of his six starts. Still, Benz had forged a promising beginning in Chicago, his prospects enhanced by a solid relief outing during the annual postseason series against the hated Cubs.15

Another career-long Benz characteristic manifested itself the following spring: early arrival at training camp in midseason condition. In between workouts one day, Benz assisted fellow staff contender George Mogridge’s hotel pool rescue of floundering nonswimmer Rube Peters, another young White Sox hurler. Once Peters was safe, Joe supposedly turned to Mogridge and kidded, “Why did you pull him out? Don’t you know that he’s after our jobs?”16 Early in the regular season, Benz solidified his spot on the White Sox staff, hurling a five-hit shutout of Cleveland. Promptly elevated to the starting rotation by new manager Nixey Callahan, Benz pitched well but frequently in bad luck. His 13-17 record included seven one-run losses, often the result of poor play by White Sox infielders – perhaps an occupational hazard for a spitball pitcher.17 At season’s end, Callahan told Chicago sports scribes that Benz had been “a lot better pitcher than his record shows”18 and slotted him for a start against the Cubs in the upcoming city series. But Callahan’s faith in Benz went only so far; he permitted Benz to finish only six of 31 starts during the 1912 campaign.

Joe spent the offseason in Batesville working in the family shop, a matter that, once discovered by the Chicago sports press, earned Benz the enduring nickname Butcher Boy. Reporting to spring training early and in his customary fit condition, Benz got off to a good start in 1913. Early-season work included four strikeouts of Joe Jackson in a 13-3 win over Cleveland, and a three-hit shutout of New York. But in June arm trouble reappeared. A diagnosis of torn ligaments put Joe on the sidelines for several weeks and reduced his overall season stats to 7-10 in only 151 innings. Yet, some modest postseason consolation was afforded Benz by a three-hit, 11-inning shutout of the Cubs before 27,000 fans attending the City Series. This performance apparently spurred Joe to a last-minute decision to accompany his teammates on a world exhibition tour. Organized by White Sox owner Charles A. Comiskey and New York Giants manager John McGraw, the trip would emulate the storied 1887-1888 world tour of Al Spalding’s White Stockings and become a memorable part of Joe Benz’s life.

Residents of Batesville flocked to nearby Cincinnati to see their hero start the tour’s opening game. But alas, Joe was shelled, losing 11-2.19 Playing their way to the West Coast, the teams embarked from Seattle in November 1913, and within hours Joe and the rest of the company were below decks, suffering the effects of the rough seas that their voyage would often encounter on the Pacific. Those following the tour’s progress in Chicago newspapers were subsequently regaled with satiric dispatches by Ring Lardner and others, recounting the misadventures of “Sir Joseph Benz of Batesville Manor,” the bumpkin abroad who slept through stops at exotic ports of call, became seasick while riding a camel, and was mistaken by tourists for the Sphinx.20 The good-natured Benz took the caricatures in stride, and if his mind was somewhat distracted during the tour, it was not without cause. For just before the team’s ship departed Manila, Joe had cabled a proposal of marriage to sweetheart Alice Leddy back in Chicago. Alice promptly accepted, but the nuptials had to await completion of a five-continent trip highlighted by an audience with Pope Pius IX in Rome and a command game performance for King George V of Great Britain, who reportedly enjoyed the exhibition immensely.21 The tour arrived in New York on March 8, 1914, but Benz skipped homecoming festivities and headed straight for Chicago. Two days later, family, friends, and various White Sox teammates attended the wedding of Joe and Alice at Our Lady of Mercy Chapel of Corpus Christi Church. Immediately thereafter, the newlyweds departed for the White Sox training camp in Paso Robles, California.22 Meanwhile, St. Louis Church in Batesville accepted delivery of a magnificent organ donated to the parish by Joe upon his return from overseas.23

During that spring Benz rejected overtures from the upstart Federal League; he would remain a member of the White Sox his entire major-league career. Joe began the 1914 season strongly, posting a 1-0 victory over Cleveland in his first start. Some seven weeks later, on May 31, the Naps were the victims of Benz’s masterpiece, a 6-1 no-hitter. Joe kept it going in his next outing, holding the Senators hitless until Eddie Ainsmith was credited with a disputed ninth-inning single. Among those in attendance who thought that the hit should have been scored an error was American League President Ban Johnson, who had, but chose not to exercise, the authority to change the scorer’s ruling.24 Thus, Benz had to content himself with a one-hit, 1-0 decision over nemesis Walter Johnson, the pitching master whom Benz regularly volunteered to face but rarely beat.25

Benz was the workhorse of the 1914 White Sox staff, leading the team in appearances (48) and innings pitched (283⅓) while posting a 2.26 ERA. But poor support and habitual hard luck reduced Benz’s log to 15-19 for the sixth-place White Sox. Ill fortune followed Joe in the offseason, as well. He was stricken by a serious case of typhoid fever and did not fully recover until the next spring. Benz’s belated 1915 debut, a three-hit win over the Browns, was promising, but he was not his previous self. Used more cautiously, he posted a 15-11 record with a 2.11 ERA over 238⅓ innings as the White Sox surged into the first division.

By 1916 the respect that Joe had accumulated around the American League was reflected in a preseason column penned by Browns veteran Jimmy Austin, who placed Benz among the “Six Hardest Pitchers I Ever Faced.”26 But age and recurring arm trouble were beginning to take their toll. No longer a rotation mainstay, Benz was used in spots, with starts often reserved for the Athletics and Senators, Joe’s perennial patsies. By season’s close he had logged only 142 innings, going 9-5 with a career-low 2.03 earned-run average. Joe spent the winter in Chicago, where his new Buick quickly became a familiar sight on the city streets.27 He also attended organizing sessions of a new players union but was outspoken in opposition to strike talk.28 As the 1917 season approached, there was far more consequential strife on the horizon but Joe, like fellow White Sox hurler Eddie Cicotte, was already beyond World War I draft age. Used only sporadically that year, Benz closed a 7-3 season with a complete-game six-hit win over the Washington Senators. Joe was included on the postseason roster of the pennant-winning White Sox but saw no action in the 1917 World Series conquest of the Giants. His only appearance against New York came in a post-Series soldiers’ benefit game played on Long Island. Still, Joe reveled in being a member of the new baseball champions, a joy only heightened by the arrival of Joseph Louis Benz, Jr., born at home in Chicago on November 10, 1917.

Despite being set back by a severe winter cold that worsened into pneumonia, Benz maintained his practice of being an early arrival in training camp for the 1918 season. Hampered by a hand injury and ineffective in his initial outings, Joe startled his teammates by announcing that he was abandoning his now unreliable spitter.29 Second thoughts quickly set in and days later Benz threw a spitball-aided complete game at the Browns. The last highlight of Benz’s big- league career came in late July, when he whitewashed Johnson and the Senators, winning 1-0 without striking out a single batter in 13 innings. Benz finished the 1918 season at 8-8, with a 2.63 ERA in 154 innings.

With World War I shortening the season, Joe returned to an offseason job in a Chicago steel mill. And like a multitude of other idled MLB players, he hooked up with local semipro teams, pitching into the late fall. The following season, Benz broke camp with the White Sox but made only a single 1919 appearance, a two-inning relief stint. He was released by the Sox in mid-May after refusing assignment to Kansas City of the American Association.30 His final major-league mark was 77-75, with 17 shutouts and a lifetime 2.43 ERA in 1,359⅔ innings – a record Benz would always take justifiable pride in.

The end of his major-league career did not sever Benz’s connection to baseball. For the remainder of the year he pitched on weekends for various Chicago area semipro teams. In the meantime the White Sox, sparked by the play of soon-to-be-banished Eddie Cicotte, Joe Jackson, Buck Weaver, Lefty Williams, et al, captured the American League flag. While the games of the infamous 1919 World Series were in progress, Benz served as the featured attraction at the Auditorium Theater, where ticketless White Sox fans could follow game action on an electronic scoreboard.31 Thereafter, Benz spent several more summers pitching in the Chicago semipro ranks. The years after he hung up the glove entirely were largely happy ones, the arrival of daughter Rita in 1922 making the Benz family complete. Benz lived a modest but comfortable life, supporting the family as a tavern owner, stationary engineer, surveyor, and church custodian.

In January 1927 he was briefly back in the news, one of the many former White Sox players summoned to Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis’s inquiry into Swede Risberg’s claim that the White Sox had bribed the Tigers during the 1917 pennant chase. Benz branded the allegation “absolutely, a lie.”32 Ultimately, Landis came to the same conclusion, taking no action in the matter.

During the 1930s Benz periodically suited up for old-timers’ games at Comiskey Park and during World War II was active in support of the war effort, once helping to sell $721,000 in War Bonds between games of a White Sox-Yankees doubleheader.33 Notoriety of a different sort attached to a 1939 court appearance during which his position as custodian of St. Killian’s Church obliged him to testify against a young man accused of theft from the poorbox. Although it had been 20 years since Benz had pitched for the Sox, Judge Joseph Hermes immediately recognized him and fondly reminisced about seeing Joe and his mates play – before dispatching the miscreant to jail for six months.34

For the remainder of his life, Joe operated a neighborhood tavern near Comiskey Park and was frequently in attendance at Chicago sports banquets, usually seated with old friends Red Faber and Ray Schalk. In January 1954 Benz was the guest of honor at the annual dinner of the Pitch and Hit Club, and the butt of genial gibes by featured speaker Lefty Gomez.35 In February 1957 Joe and old White Sox pals were together again at the yearly winter fete of the Chicago Old Timers, a local baseball organization of which Benz was a vice president. Two months later he was felled by a stroke. Benz died in Chicago on April 22, 1957. He was 71 and was survived by his wife, children, and brother Mike.36 A good pitcher and a kindly man, Joe Benz’s passing was noted sadly by the baseball world.37 He rests with family in Chicago’s Holy Sepulchre Cemetery.

Notes

1 The Benz siblings were Michael Jr. (1884-1964), Martha (1890-1907), and Leo (c. 1892-1952). Joe’s parents also raised orphaned cousins Hugo and Matilda Benz.

2 As per Minnie S. Wycoff, Builders of a City (Batesville, Indiana: Batesville Area Historical Society, 2003), a posthumously published local history kindly provided to the writer by genealogist Denean Williams of the Batesville Memorial Public Library. Information on the Benz family was also gleaned from the “Memory Lane” column of Granny (Elizabeth Ollier), published in the Batesville Herald Tribune, May 1, 1952.

3 Batesville Herald Tribune, June 14, 1997.

4 A capsule summary of notable games Benz pitched for the hometown nine in 1908 was published in the Batesville Herald Tribune, July 12, 1951.

5 Batesville Tribune, March 24 and April 14, 1909, and reiterated in the Washington Post, September 30, 1917. In his Clarksburg debut, Joe held the opposition hitless, striking out eight, before a fifth-inning muscle pull in his upper arm necessitated his removal from the game, as per the Batesville Tribune, April 21, 1909.

6 As reflected in the box score published in the Batesville Tribune, June 2, 1909. The 1909 Batesville team photo also features Joe and his older brother Mike, an infielder.

7 See baseball-reference.com/minors/team.cgi?id=26877 for Joe Benz’s record with Newark.

8 Baseball-Reference.com has no record of Benz pitching for Des Moines in 1909 but his membership on that team is noted in the Batesville Tribune, October 6, 1909, and confirmed in various 1910 preseason reviews of Boosters prospects. See, e.g., Des Moines News, March 30, 1910, Des Moines Register & Leader, April 1, 1910.

9 Des Moines News, April 30, 1910.

10 As reported in the Des Moines papers, May 18, 1910. Said the Evening Tribune: “There is no question but that Benz has a lot of pitching ability in him but thus far he has not been able to get going in the Western League.” Strangely, Baseball-Reference.com has no 1910 data whatever for Benz. From the reportage of the 1910 Des Moines press, the writer calculates Benz’s Boosters pitching record as 0-1, with one save, in six appearances.

11Based upon game accounts and box scores published in the Green Bay Gazette and the Green Bay Semi-Weekly Gazette, the Joe Benz Green Bay pitching log appears to be 20 games (19 starts, 1 relief appearance), 177⅓ innings pitched, and a 9-8 won/lost record, with 103 hits allowed, 111 strikeouts, 23 walks, 17 complete games, and 0 saves. The writer is indebted to historian David Williams of Madison for helping research Benz’s tenure with Green Bay.

12 Des Moines Register & Leader/Des Moines Daily Capital, October 6, 1910.

13 The oft-told tale that Benz’s acquisition by the White Sox was occasioned by correspondence between Joe’s father and White Sox owner Comiskey is apocryphal. But a January 1910 letter from Comiskey to Joe himself (thanking him for New Year’s good wishes and reminding Joe that he was under contract to Des Moines team owner John F. Higgins) is contained in the slim collection of Joe Benz papers on file at the Chicago History Museum.

14 Chicago Tribune, August 17, 1911.

15 Pitching once again in relief of Doc White, Benz’s two scoreless frames “won him lasting laurels and the respect of everybody,” according to the Chicago Tribune, October 15, 1911.

16 Chicago Tribune, February 26, 1912.

17 As a major leaguer, Benz pitched to contact, averaging less than 4 strikeouts per 9 innings during his career. In 1912 Benz compounded his infield problems by being an unsteady fielder himself, recording 10 errors of his own that season.

18 Chicago Tribune, October 2, 1912. Burgeoning regard for Benz is also reflected in the United Press Syndicate circulation of a first-person column under a Joe Benz byline that season. See the oddly titled “My Batting Jinx,” Los Angeles Times, August 12, 1912, and elsewhere.

19 The October 19, 1913 Chicago Tribune account of the game was subheadlined, “Joe Benz Slaughtered.”

20 See the Chicago Tribune, January 26-February 22, 1914, passim.

21 See generally, G.W. Axelson, Commy: The Life Story of Charles A. Comiskey (Chicago: Reilly & Lee, 1919), 156-185. See also Chicago Tribune, March 29, 2000. Benz pitched in the game attended by the King, the last contest of the tour and played before a crowd reported at 35,000.

22 Months before his own marriage, Joe was in attendance when cousin Charlotte Benz was wed to fellow WhiteSox hurler Reb Russell, Joe’s boarding-house roommate.

23 As recalled by Joe’s nephew, Hugh J. Benz of Batesville, email to the writer, March 31, 2011.

24 Washington Post, June 12, 1914.

25 Johnson held a 10-2 advantage in decisions involving the two pitchers.

26 Boston Globe, March 21, 1916. The others were Walter Johnson, Joe Wood, George Dauss, Guy Morton, and Jim Scott.

27 A friend driving the Buick was stopped by a Chicago cop who recognized Benz’s vehicle on sight and detained the driver until Joe could be found to vouch for the friend’s permission to use the car, as reported in the Chicago Tribune, January 17, 1917.

28 Said Benz: “I have been well treated by the magnates and I believe it is up to every ball player to look out for his own interests,” as per the Chicago Tribune, January 14, 1917.

29 Atlanta Constitution, June 24, 1918.

30 Chicago Tribune, May 17, 1919. In addition to being separated from family, Joe was disinclined to pitch in the American Association, a league that had just outlawed the spitball.

31 As advertised daily in the Chicago Tribune and elsewhere.

32 Chicago Tribune, January 5, 1927.

33 Chicago Tribune, July 20, 1944.

34 Chicago Tribune, January 17, 1939.

35 Chicago Tribune, January 29, 1954.

36 Alice Leddy Benz died in 1972, age 86. Joe Jr. (1917-2006) and Rita (1922-2010), a nun also known as Sister Mary Borgia, never married and died childless.

37 Chicago Daily News sportswriter John P. Carmichael remembered Joe Benz as “one of the fine characters of baseball … a gentleman of the old school who liked to relive the days of his youth just for kicks,” in The Sporting News, May 1, 1957.

Full Name

Joseph Louis Benz

Born

January 21, 1886 at New Alsace, IN (USA)

Died

April 22, 1957 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.